An original self-powered adventurer, Albert Ellingwood, walked hundreds of miles, resoling his boots in each town, and climbing difficult routes when he reached each destination. He did this wearing hobnailed boots, low-tech clothing, and carrying a heavy pack.

Finding Women in the Collections of the American Alpine Club Library

Trip to the Library, January 4th 2019

by Ron Funderburke, AAC Education Manager

At the top of this new year, I was doing some research on behalf of the American Mountain Guides Association. A question about the history of American guides came across my desk earlier last year, and I began making regular trips to uncover the overlooked and often sad history of American mountain guides prior to the professionalization of the trade. Many native guides were conscripted, and their local knowledge of mountain passes and mountain ways was never credited by the “pioneers” that exploited them. Anyone interested can check out the AMGA’s Guide magazine later this year for an article that summarizes my findings.

On January 4th, I was pursuing this little mystery:

The American Alpine Club trained and certified American mountain guides? When was that? Why did they start that program? Why did the program end? Did AMGA replace this program?

To find an answer, I started with the first editions of the American Alpine Journal, and I scanned the records of all the Club’s proceedings. Proceedings include minutes from board meetings, secretary reports, and reports from gatherings and dinners. They’re pretty thorough. I came across proceedings from the mid-1930s that disclosed the emergence of American guiding services in the Tetons and Mount Rainier and findings of the AAC board that unified training and certification would be of value for aspiring professionals and for Americans that needed the services of a guide.

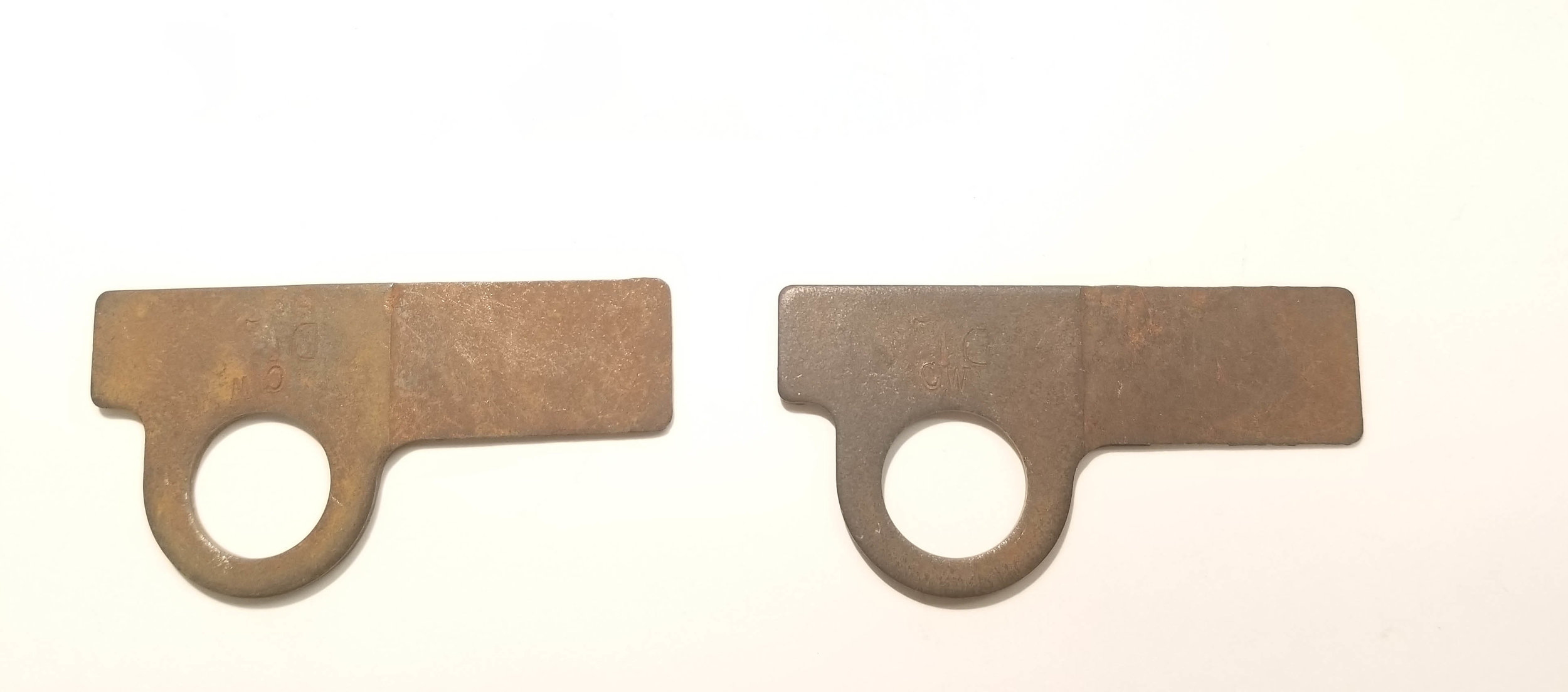

The proceedings detail the formation of a ‘Guides’ Committee’ and that committee began reporting regularly on its work. By 1940, the Guides’ Committee had run several trainings and certification exams, it had designed and distributed diplomas, and it had used these initial successes to begin planning more trainings around the country. The ‘Guide’s Diploma’ artifact that is pictured above is one of few remaining relics from this program.

What happened, you might ask? It’s difficult to know what would have happened to the AAC Guide Committee, and its training and certification scheme, had World War II not taken the entire climbing world in a different direction. After 1941 all proceedings of the Guides’ Committee were replaced with new and pressing work being done to support the American war effort, including the training, recruitment, and deployment of mountain soldiers. All the expertise American climbers could muster, and all the able-bodied soldiers that might have become guides, were enlisted in the war effort.

After the war, the guides program was taken up again in sporadic fits and starts, including some early versions of the American Mountain Guides Association in 1970. In each case, the proceedings document trainings and certifications in isolated regions of the country, and an ultimate inability to create a program that would have unified American professionals.

Additionally, I perused the Fuhrerbuch (guides log) of one of the first certified mountain guides in North America. Ed Feuz Sr was a certified Swiss Bergfuhrer (mountain guide), and he was recruited by the Canadian Pacific railroad to offer guided climbing at the mountain hotel and rail-stops along the track through the Canadian Rockies. Feuz had many American clients, and his careful record of their climbs is documented and archived. Near the end of his career, Feuz described how guided climbing had become unfashionable. It’s one of many clues I could find as to why the AAC guides committee only achieved sporadic success training and certifying mountain guides after World War II.

When our library professionals saw the nature of my research, they asked if I had seen the AMGA archives. As a long time professional member of the AMGA, I was intrigued to know what might be in those archives. I was not disappointed. I found reams of correspondence between the American Alpine Club, members of the AAC Guides’ Committee, guides and guide service owners, sponsors and consultants from the Alpine Club of Canada, the Association of Canadian Mountain Guides, and various representatives of European guides associations including the International Federation of Mountain Guides. I found lengthy treatises and pedagogical statements on the nature of American climbing instruction and education from the likes of Yvon Chouinard.

Together, the whole dossier chronicles a story about American guides that should resonate with any guide today. Guides had strong opinions about the standards to which they should be trained and certified. Guide services had strong opinions about how much certification schemes should cost and how relevant certifications would be to their operations. Climbers had strong opinions about the differentiation of guided ascents and non-guided ascents. Educators had strong opinions about how and why climbing instruction should distinguish itself from prevailing education systems of the times. With so many strong opinions and so many perspectives needed to create a system of professional guides education and certification, it’s no wonder the work of the AAC Guides’ Committee encountered so many obstacles. When strong personalities and strong opinions collide, consensus can be difficult to achieve.

Like many trips to the library, my quest to solve one little mystery unveiled new mysteries, and the questions I was pursuing are not generally of interest to climbers. It’s the kind of esoterica that you can’t uncover on Wikipedia. Thankfully, our library and our library professionals appreciate that little things will matter to someone, some day.

Mountain Dont's

In 1925 Albert H. MacCarthy had just led a successful first ascent of Mount Logan in Canada, composed of climbers from Canada, Britain and the United States. MacCarthy, an American and member of the American Alpine Club, wrote a number of reports and summaries of the expedition, including this list of Mountain “Dont’s.”

Pitons

by Allison Albright

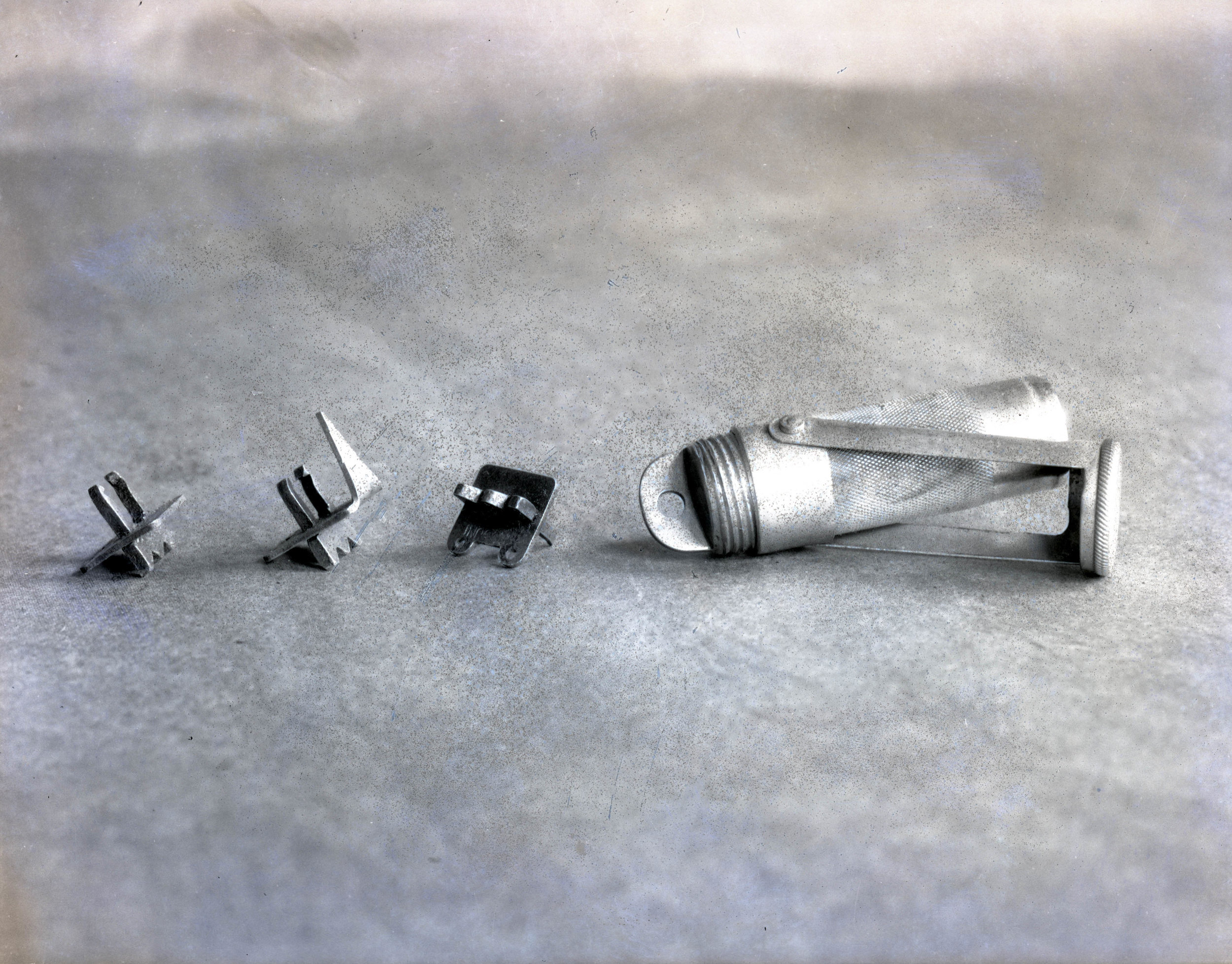

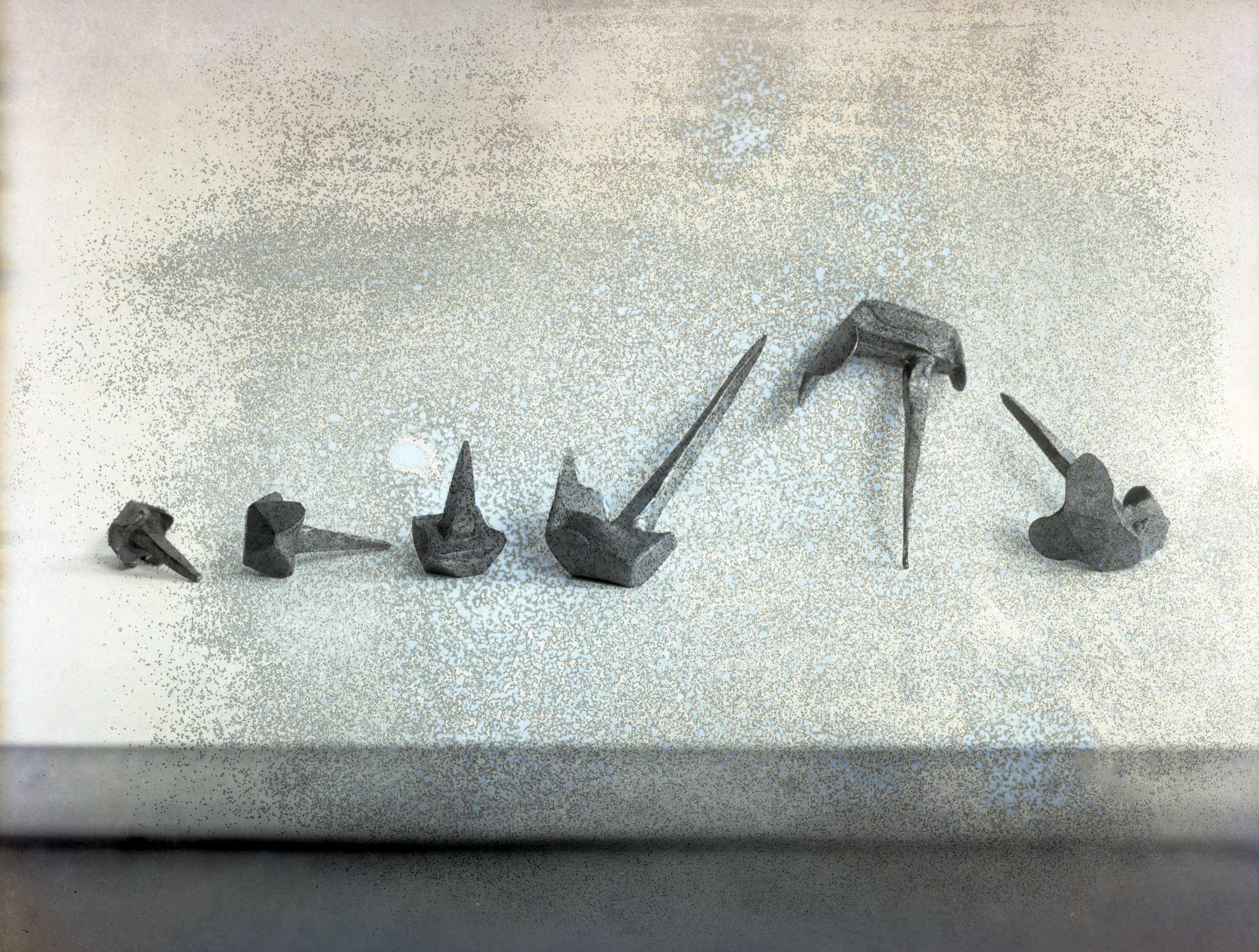

A set of pitons from the mid-20th century, including LEM, Charlet-Moser, Stubai and Chouinard

Pitons are one of the oldest types of rock protection and were invented by the Victorians in the late 19th century. Pitons are metal spikes which are inserted into cracks in the rock and secured by hammering them into place with a piton hammer.

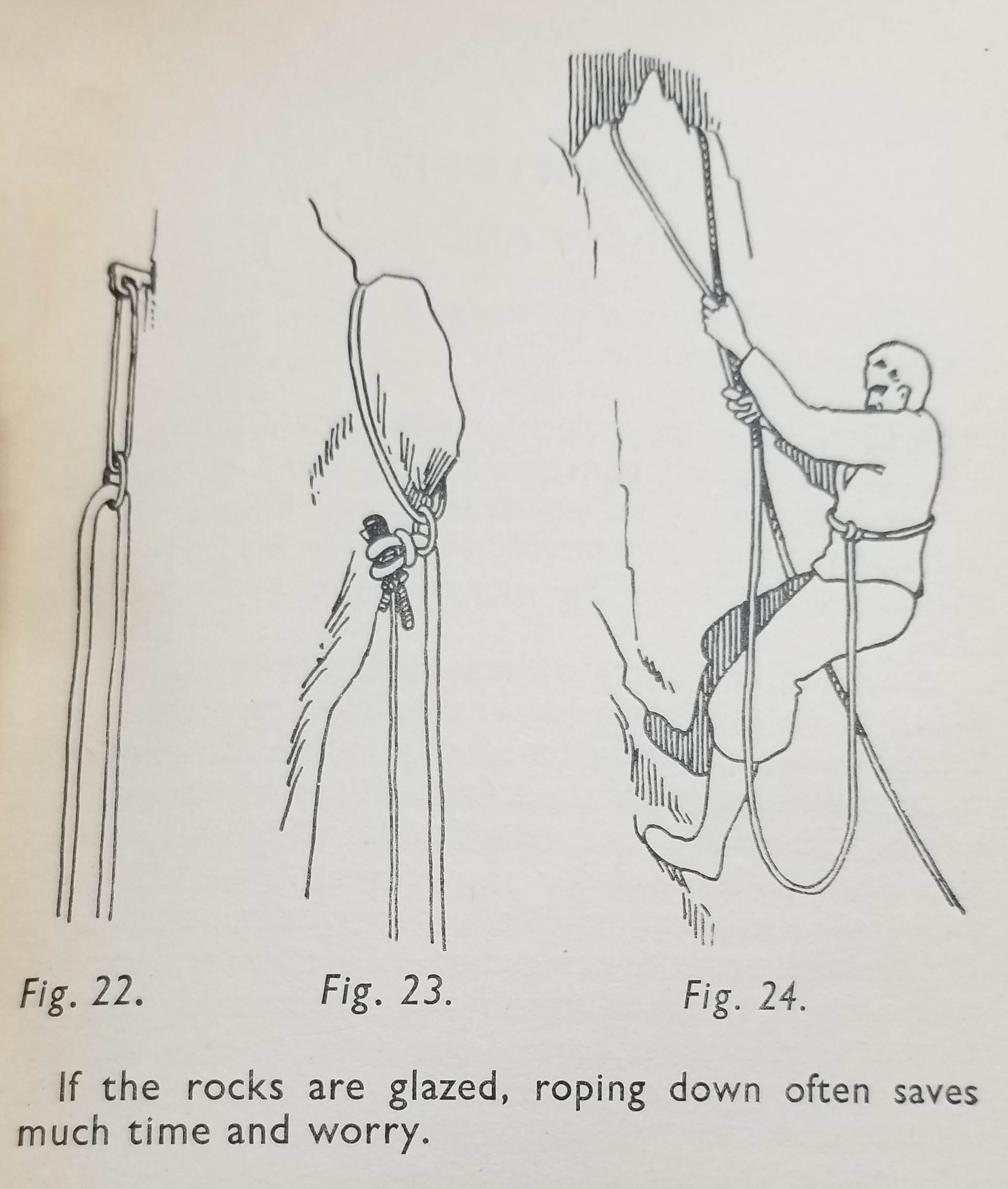

Illustration of a climber using natural protection methods to rope down from Alpine Climbing on Foot and with Ski by Ernest Wedderburn, 1937

Mountaineering involved technical rock climbing only as a means to reach the top of the mountain, and not, in those days, for its own sake and by the turn of the 20th century, most mountain climbers favored “natural protection,” which was securing rope to rocks or other natural features that could be found along the route. They used pitons nearly exclusively for climbing down and only then when the route down had become unsafe due to the sun setting or ice forming on rocks. This was especially true of UK mountaineers, who prided themselves on their ability to climb without the use of such aids.

Many mountaineers in those days believed that the use of artificial rock protection and aids, such as pitons, would lead to carelessness and were regarded as useless in the ascent of difficult routes.

Early pitons were iron spikes and had rings attached to one end through which mountaineers would secure their rope. However, those rings sometimes bent or broke under the weight of a mountaineer. Hans Fiechtl invented the modern piton in 1910, made entirely of one piece of metal with a hole (called the eye) in one end. This reduced the number of moving parts in the tool and made them sturdier and more reliable.

Illustration of piton use and placement from the Handbook of American Mountaineering by Kenneth Henderson, 1942

“In such cases, pegs to hammer in and anchor to are a remedy for our failures, our failure to carry on, to adjust the climb to the day-length, or to watch the weather. Their use then is corrective, not auxiliary.”

Angle piton with a ring

Illustration of proper piton technique from the Handbook of American Mountaineering by Kenneth Henderson, 1942

Pitons were mostly made of softer steel and iron that allowed them to conform to the shape of the crack when used, making it difficult or impossible to remove them from the rock when they were no longer needed. This method worked well in the softer rock of Europe and much of the US, and pitons were habitually left in place at the end of a climb.

However, leaving permanent marks on the landscape sat poorly with many climbers and soft pitons didn’t work well on longer routes where rock protection needed to be removed and used again. They also didn’t hold up well in the hard granite of places like the Yosemite Valley. In 1946 John Salathé, a climber and a blacksmith, used hardened steel to create pitons that could be removed from a crack and used again and again without getting bent or disfigured.

A lost arrow piton with sunburst design

The only problem with the harder pitons was that they often disfigured the rock. Since pitons are hammered into and out of rock cracks, and since the same cracks are often used over and over again, climbers were leaving their mark each time they inserted and removed a hard steel piton. The soft steel pitons weren’t much better at leaving a route unaltered, since they often had to be left in place. They can still be found in some routes.

“There is a word for it, and the word is clean.” – Doug Robinson, The Whole Natural Art of Protection, 1972

Yvon Chouinard, who had been making pitons through his Chouinard Equipment brand for several years by then, introduced the aluminum chocks in his 1972 Chouinard Equipment/Great Pacific Iron Works catalog. The catalog included two seminal essays on clean climbing; A Word by Yvon Chouinard and Tom Frost, and The Whole Natural Art of Protection by Doug Robinson. You can read them online here. This ethos changed American climbing forever and the piton was quickly replaced by equipment that could be easily removed and reused without damaging or altering the rock, first slings, nuts and chocks and later cams.

Pitons manufactured by Yvon Chouinard, arranged in order of their evolution.

Clean climbing methods proved to be much safer and easier to use than pitons, since pounding a spike into a crack with a hammer is time and energy consuming. Pitons are still used in some places where other types of protection aren’t an option, but these situations are rare.

You can check out some examples of pitons from our archival gear collection in the slideshow below.

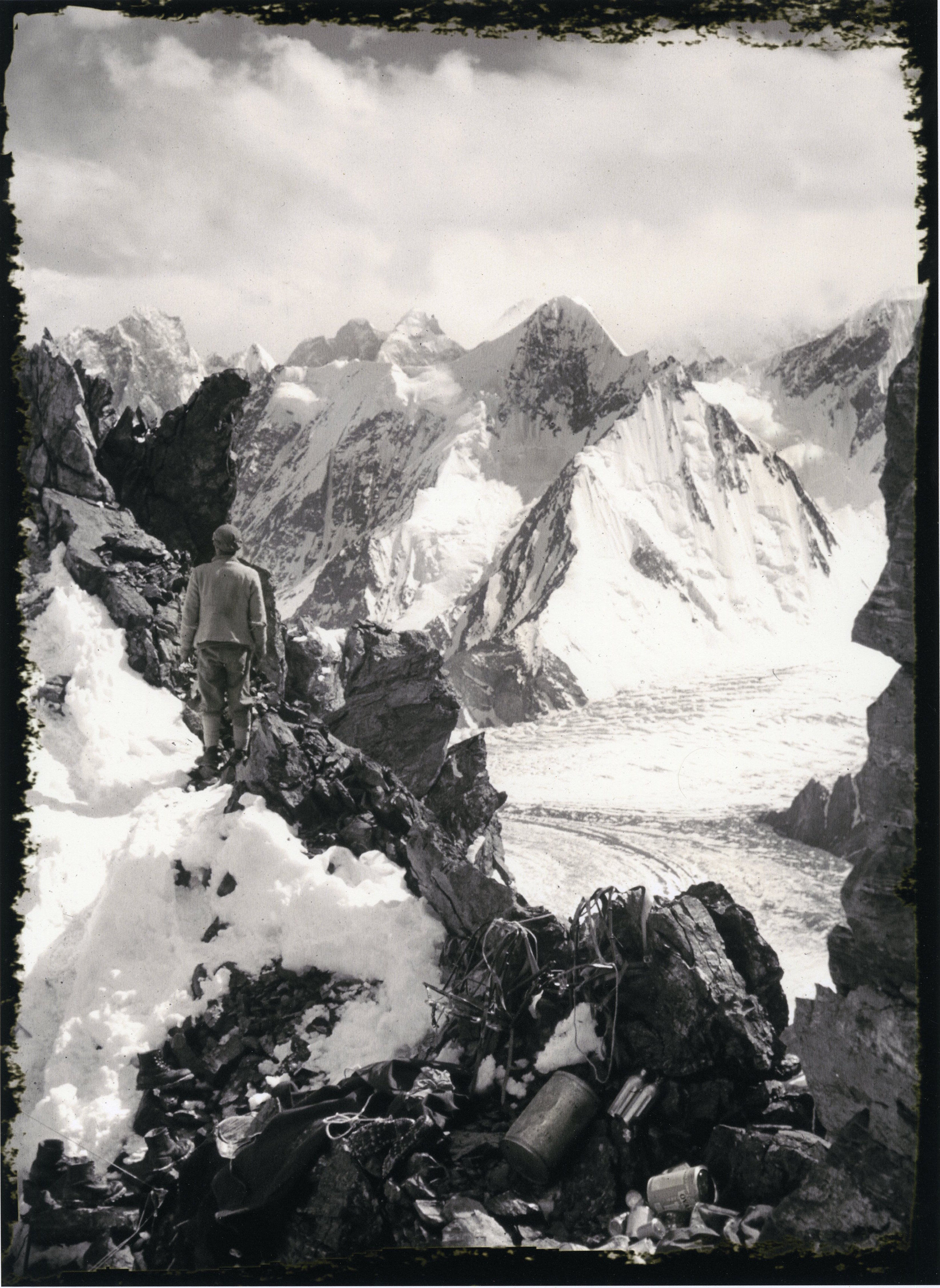

Denali - First ascent of the South Face via the West Rib 1959

It had all begun on an afternoon some nine months previous. Four of us were lying about relaxing after a particularly fine Teton climb when someone enthusiastically suggested, "Let’s climb the south face of McKinley next summer!” To attempt a new and difficult route on North America’s highest mountain seemed a most worthwhile enterprise; without further ado, we cemented the proposal with a great and ceremonious toast.

Last Minute Halloween Costume Ideas

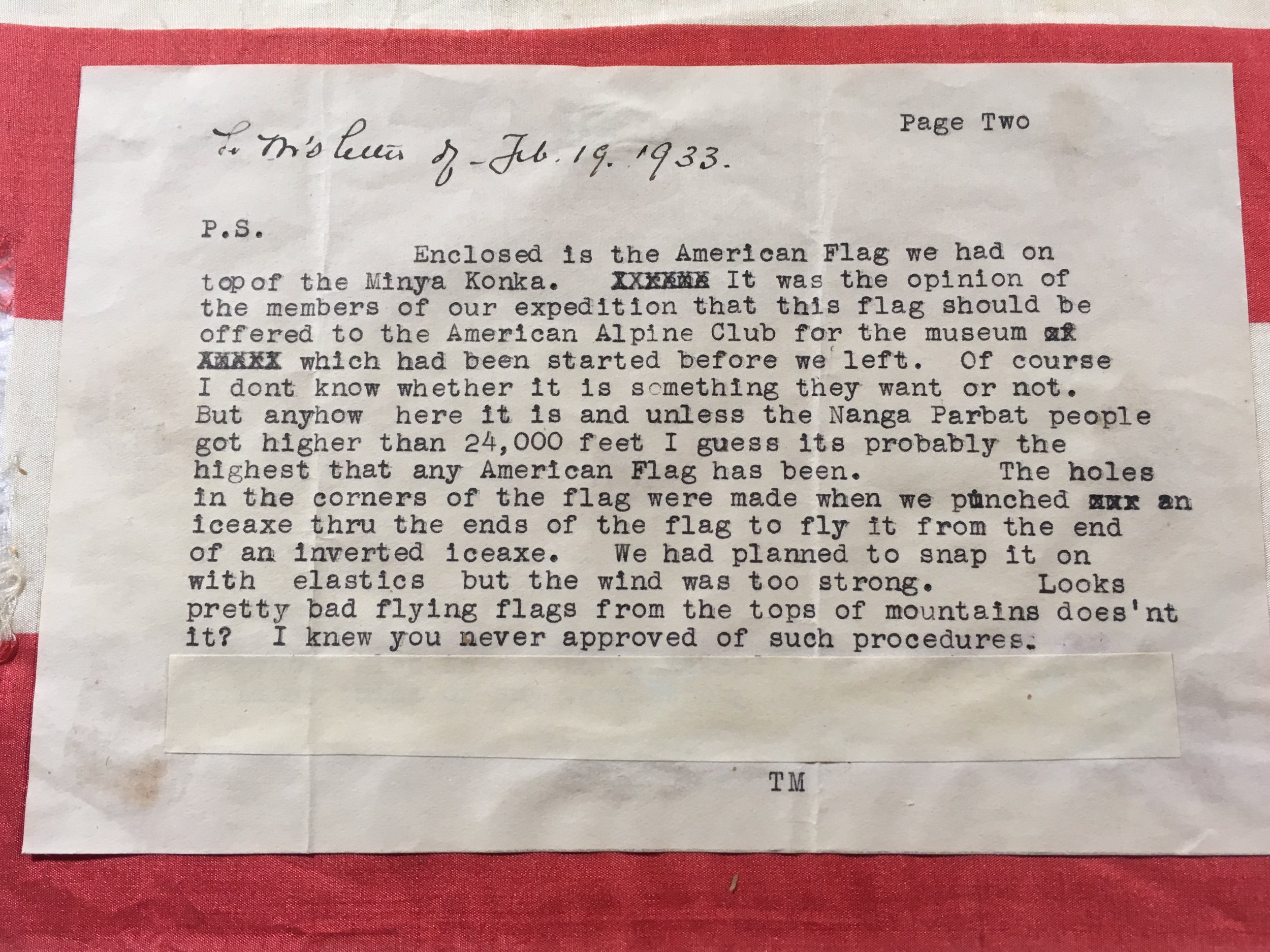

Gongga Shan (Minya Konka) 1932

by Eric Rueth

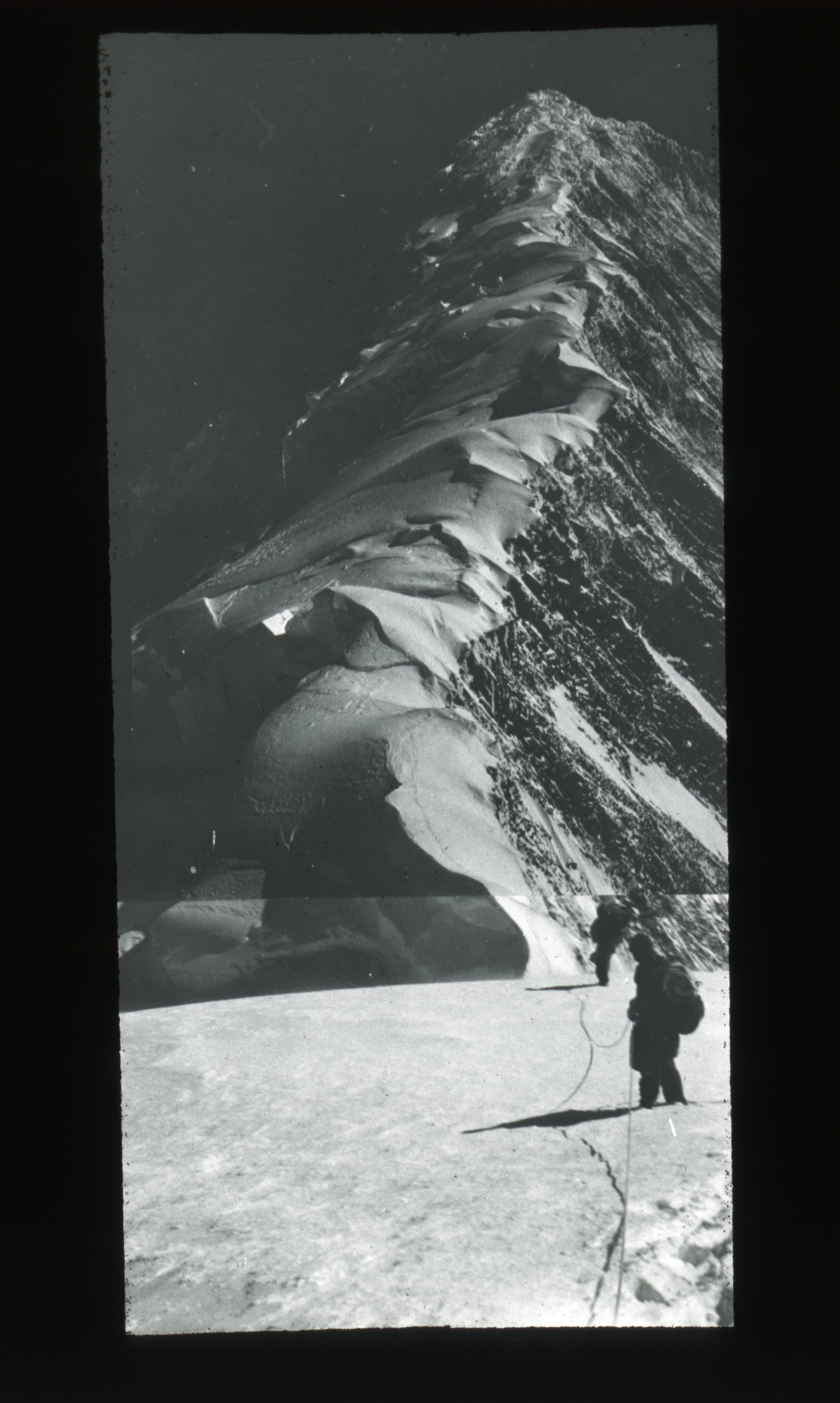

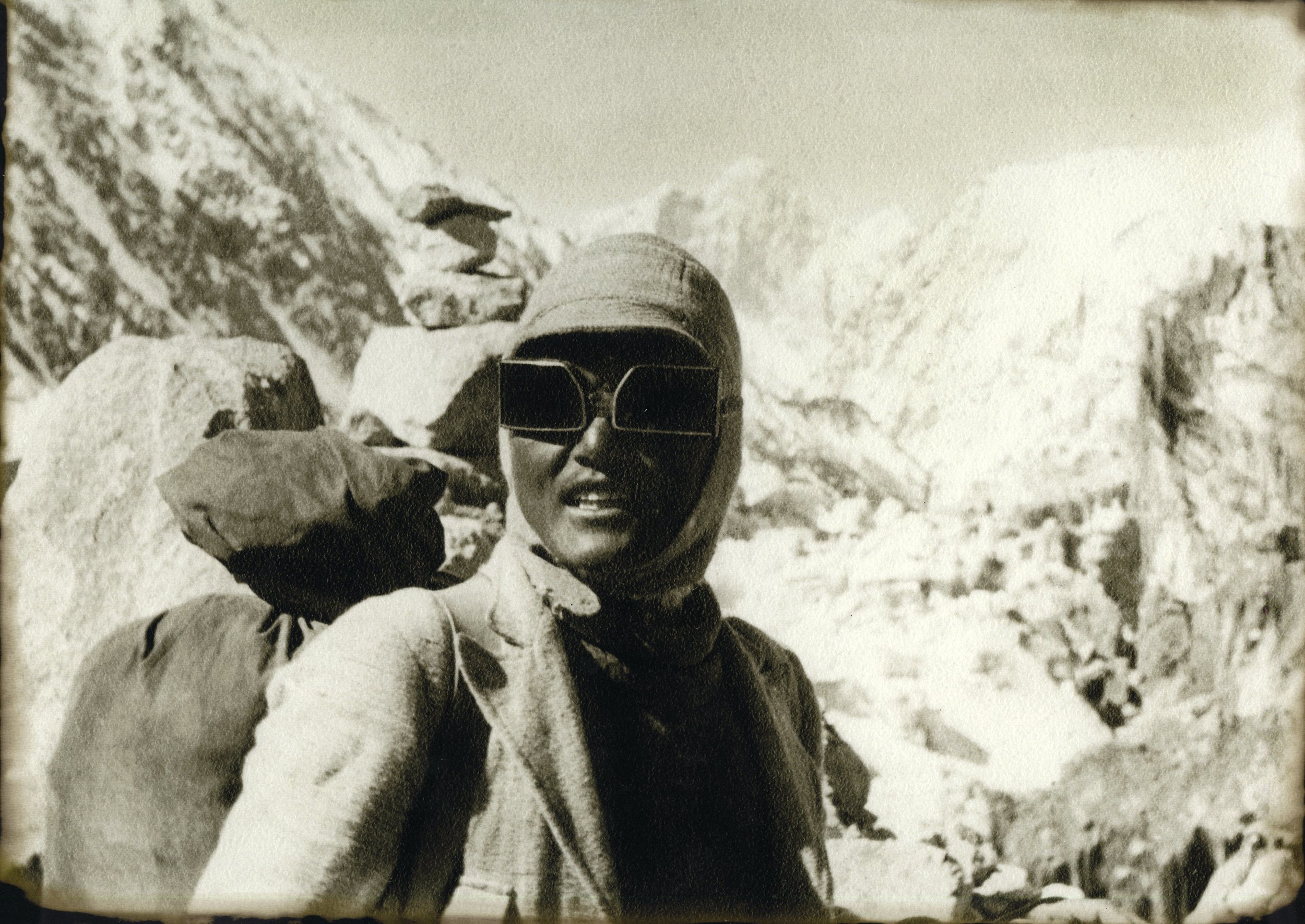

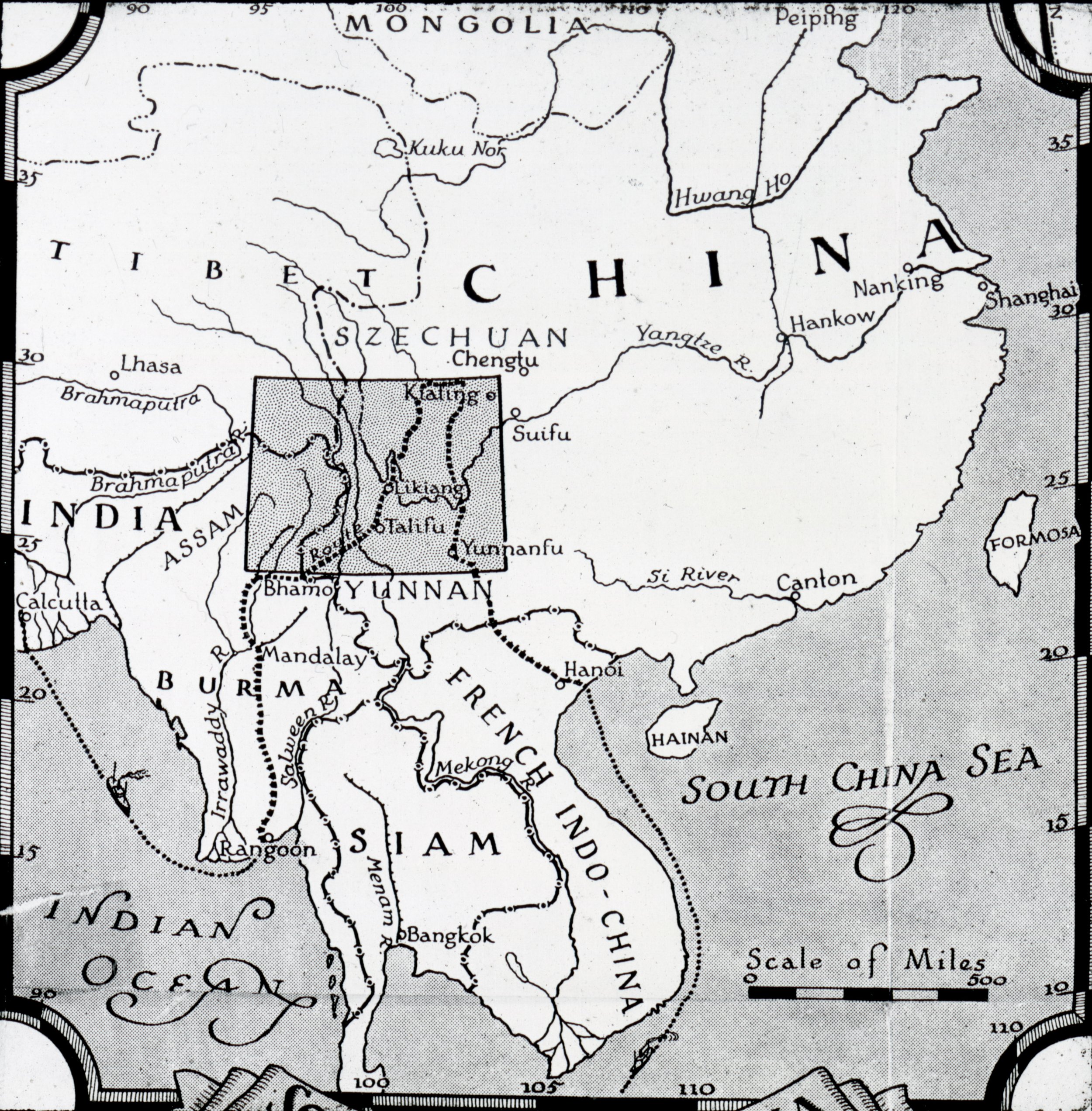

The Sikong Expedition in 1932 has to be one of the more unique mountaineering tales to have ever occurred. I and maybe others would argue that if there ever was a mountaineering expedition that should be turned into 1990’s style action-adventure movie starring Brendan Fraiser, this one would be it. There are too many interesting details to this expedition to fully capture in a blog post like this, so instead I’m going to give you a bare bones description and show you some of Terris Moore’s slides in an attempt to get you to read the American Alpine Club Journal articles about the expedition (linked below), and/or to read the entire book of the expedition (prologue through the epilogue), Men Against the Clouds. The pieces written by the expedition members themselves are really the only pieces of writing that do this expedition justice.

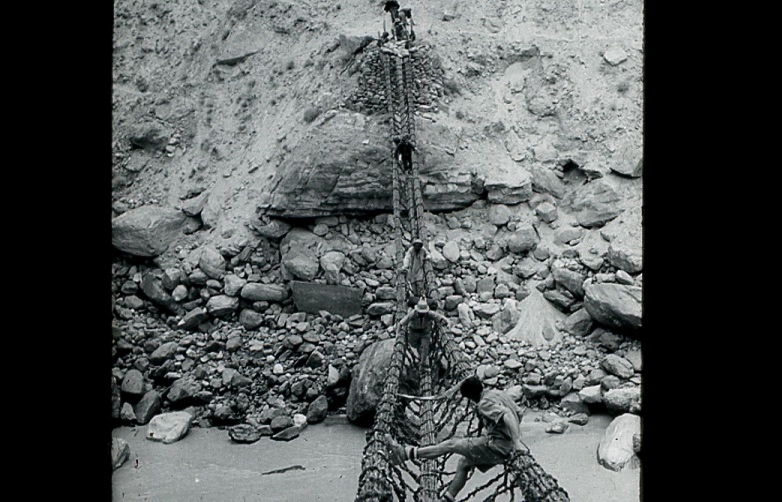

The Sikong Expedition consisted of four Americans, Jack Young, Terris Moore, Arthur Emmons, and Richard Burdsall. These were the four remaining members of a larger Explorers Club expedition that was meant to take place but dissolved due to various delays and complications created by global events. One of the global events was the Japanese invasion of Shanghai which led Young, Moore, Emmons, and Burdsall to briefly become a part of the American Company of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps.

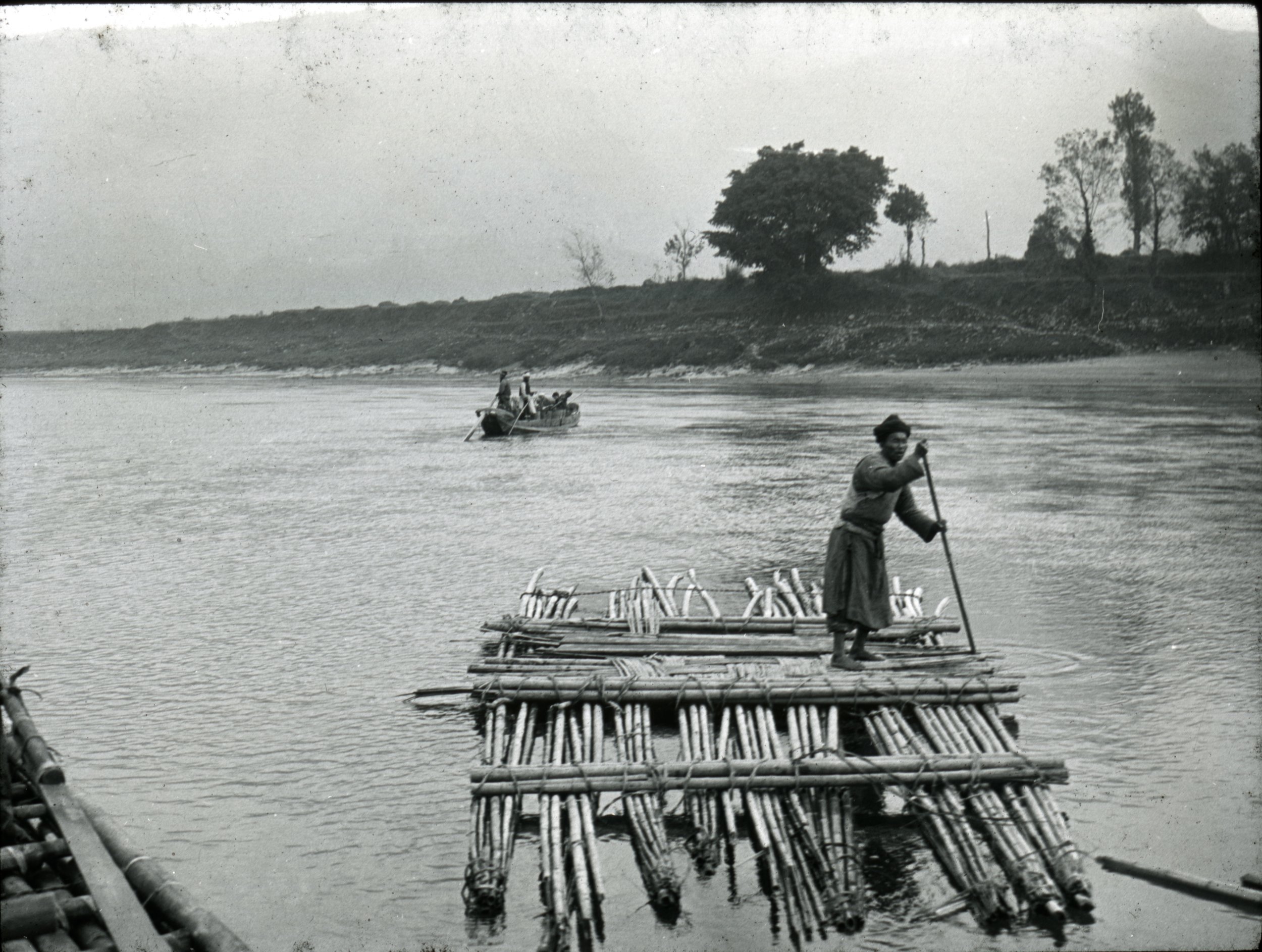

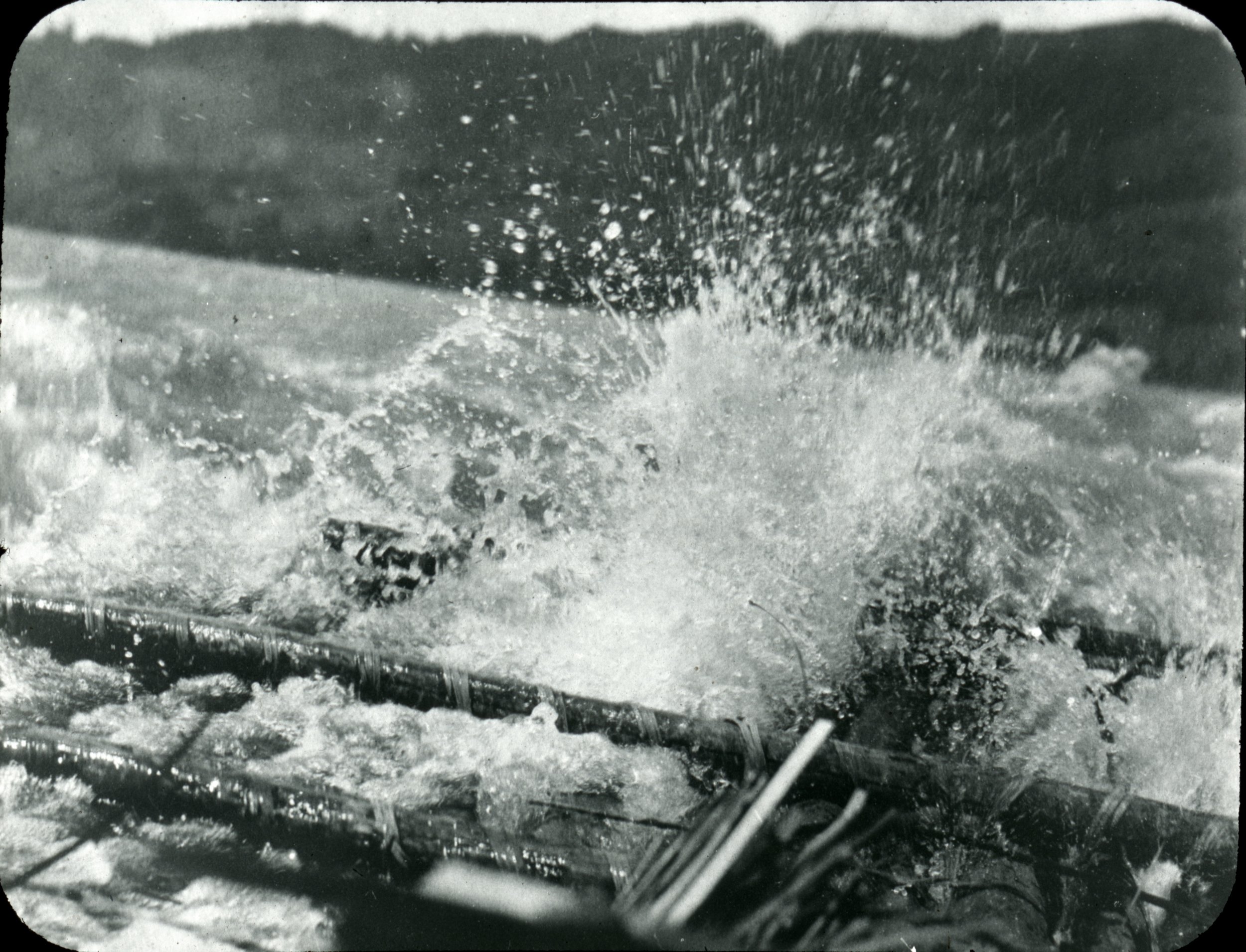

After the dissolution Lamb Expedition to Northern Tibet, the first step of the newly formed Sikong Expedition was a twenty day journey up the Yangste River that featured rough waters, beautiful gorges and potential for pot shots from bandits on the river banks.

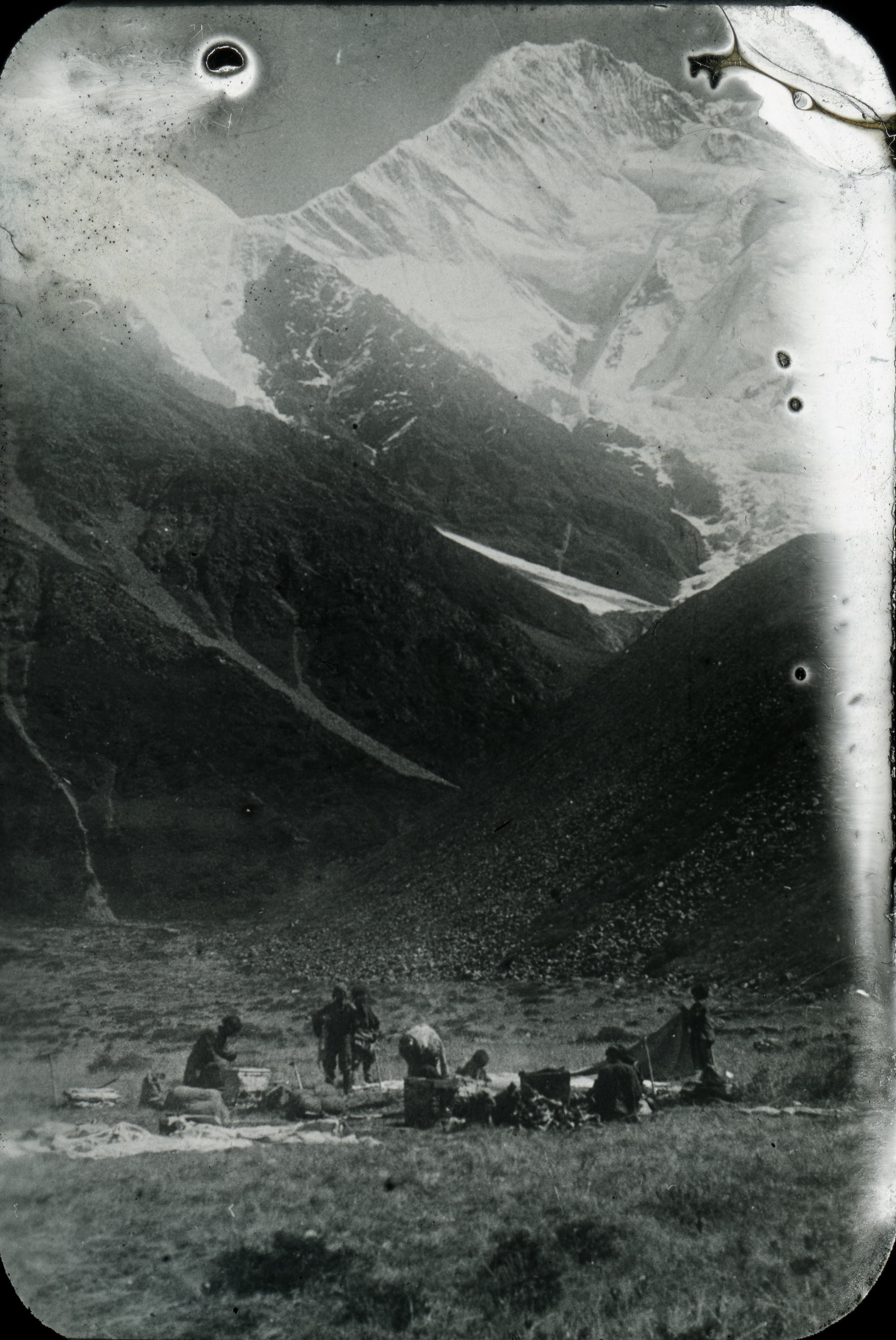

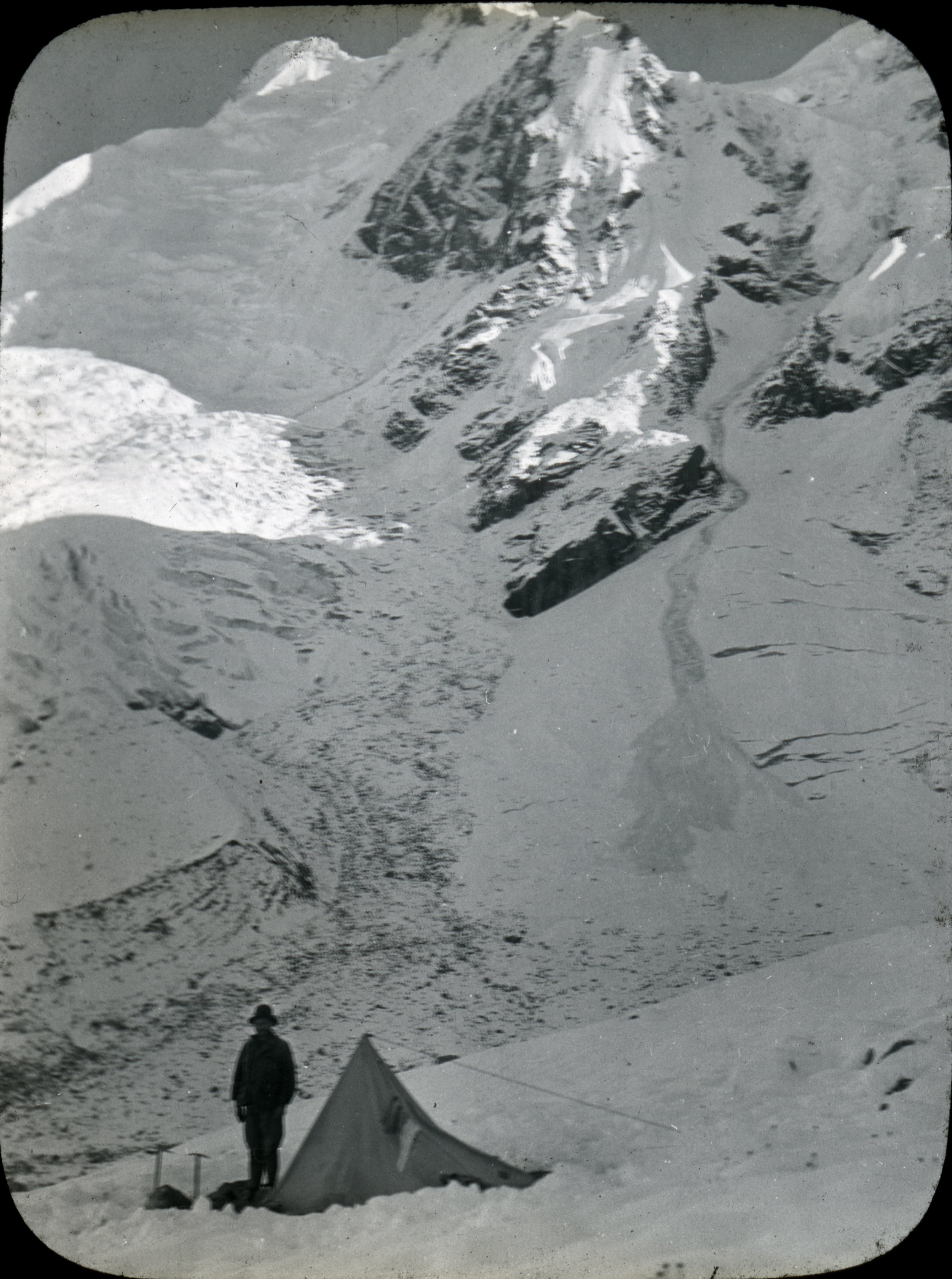

The Sikong-Szechuan region was still relatively unknown to the west and the purpose of the original expedition was to explore survey the region and gather samples of flora and fauna along with an attempt on Gongga Shan. The explorer’s spirit lived on in the Sikong Expedition. Thirty pages of appendices and one AAJ Article document their efforts. Below are two slides that not only shows the expedition doing some survey work but also shows how photographs and slides can degrade over time! If your interested in degrading photographs check out this previous library blog post.

Part of the reason for surveying the region and the mountain specifically was that at the time calculations of its height ranged anywhere from 16,500’ to 30,000’. The Sikong Expedition measured Gongga Shan’s height to be 24,891’ which is only 100’ off of the mountain’s current measured height of 24,790’.

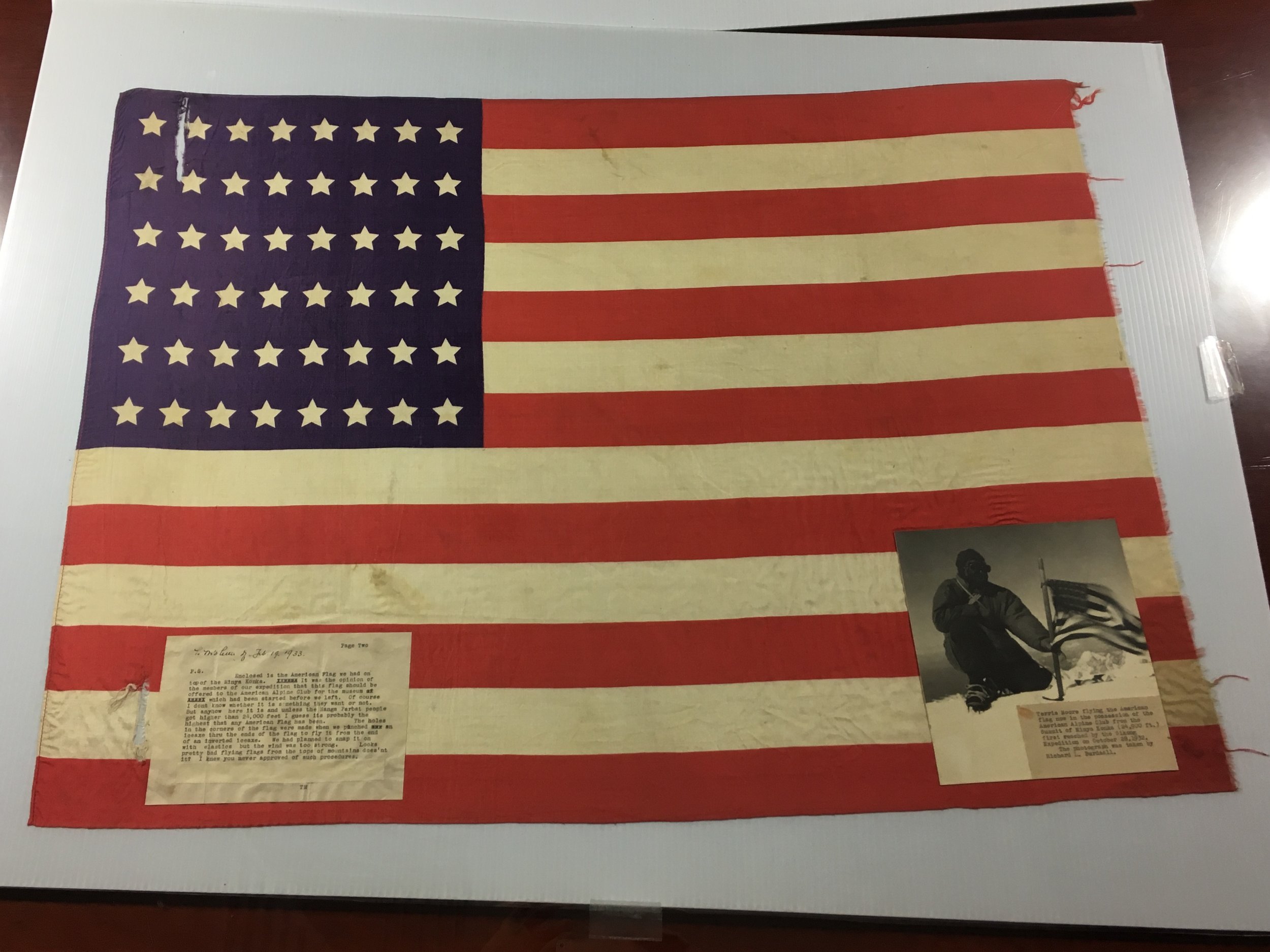

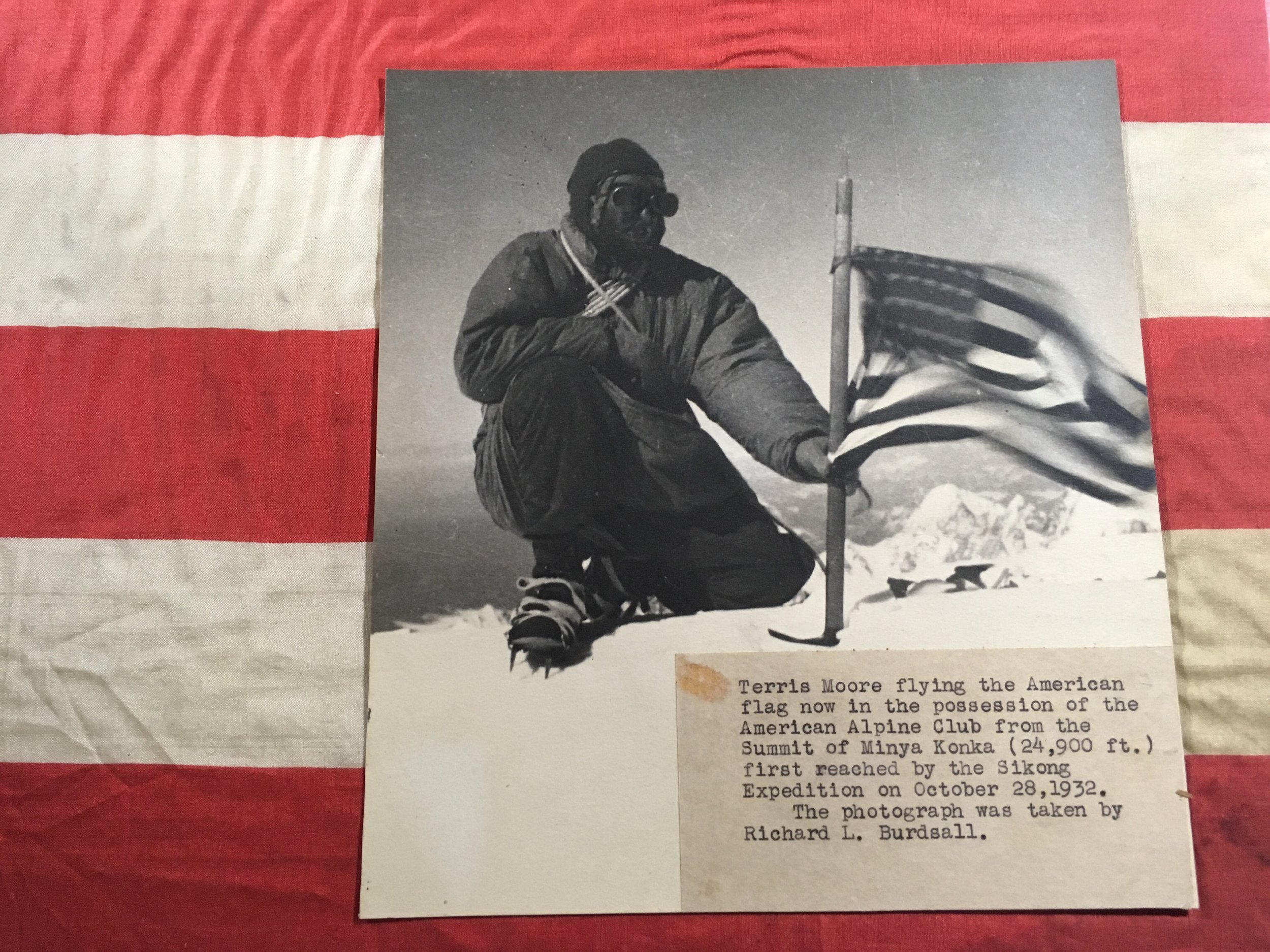

After weeks of acclimatization, moving supplies, and setting up camps, no high-altitude porters and with crevasse falls along the way; Moore and Burdsall attained the summit on October 28, 1932. Below are two of the dozens of photos taking while on the summit. Photographs were taken with the Chinese flag and the American flag. The American flag (48 stars) carried to the summit currently resides here at the American Alpine Club Library. Due to wind, an ice axe had to be pushed through the flags to keep them attached and flying for the summit photos.

What makes this expedition such an amazing feat is the twists and turns that take place in the story. The expedition in a sense never should have happened after the Lamb Expedition dissolved. Under normal circumstances it is likely that everyone would have headed home and planned to try again at a different time. Instead, four members remained in large part due to the Great Depression and being told that their money would fair them better in China and that there likely wouldn’t be work for them if they returned to the States. The style that the mountain was summited was more akin to modern expeditions than it was to the siege the mountain strategy that tended to be the norm for the day. Despite not receiving much plaudits at the time, Gongga Shan was the highest summit reached by Americans at the time but the expedition was able to help fill in one of the few remaining blanks on the map.

If you’re an American Alpine Club member you can checkout Men against the clouds by logging into the AAC Library Catalog.

And regardless of if you’re an AAC member, you can find AAJ articles written about the expedition by following the links below:

Terris Moore’s AAJ article about the climb

Arthur Emmon’s AAJ article about the survey work

A short article by Nick Clinch that concisely summarizes the expedition

The Andrew J. Gilmour Collection

by Allison Albright

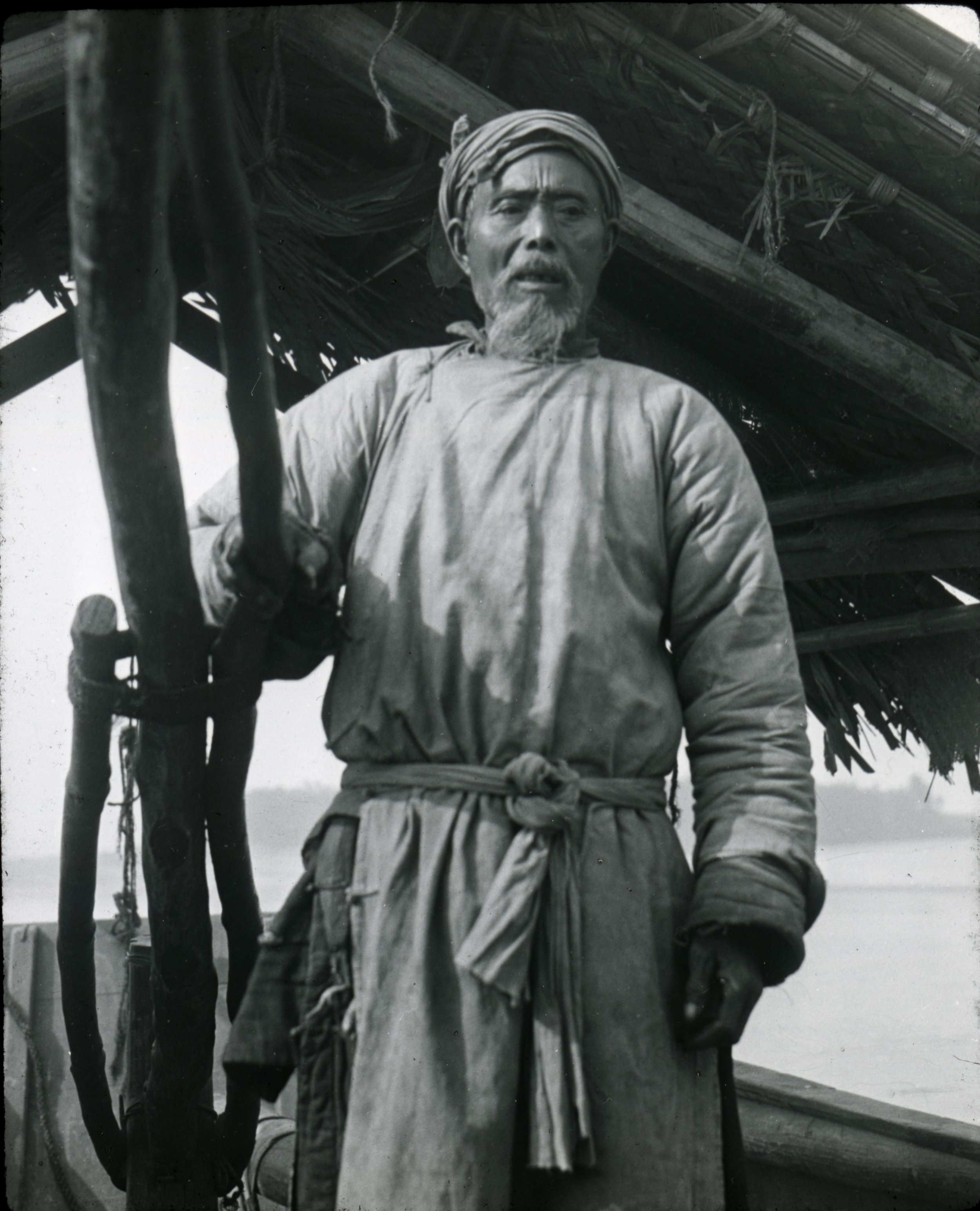

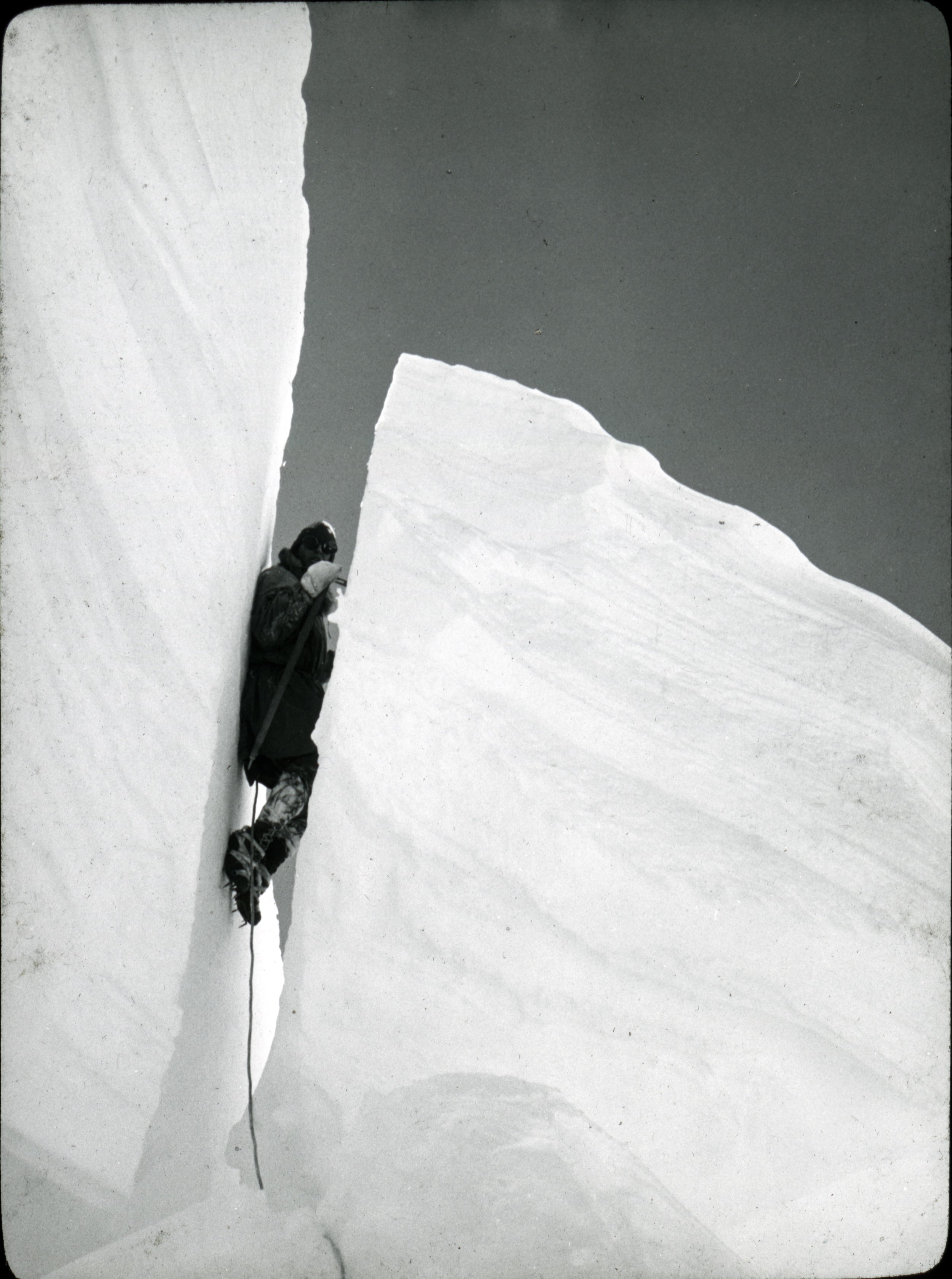

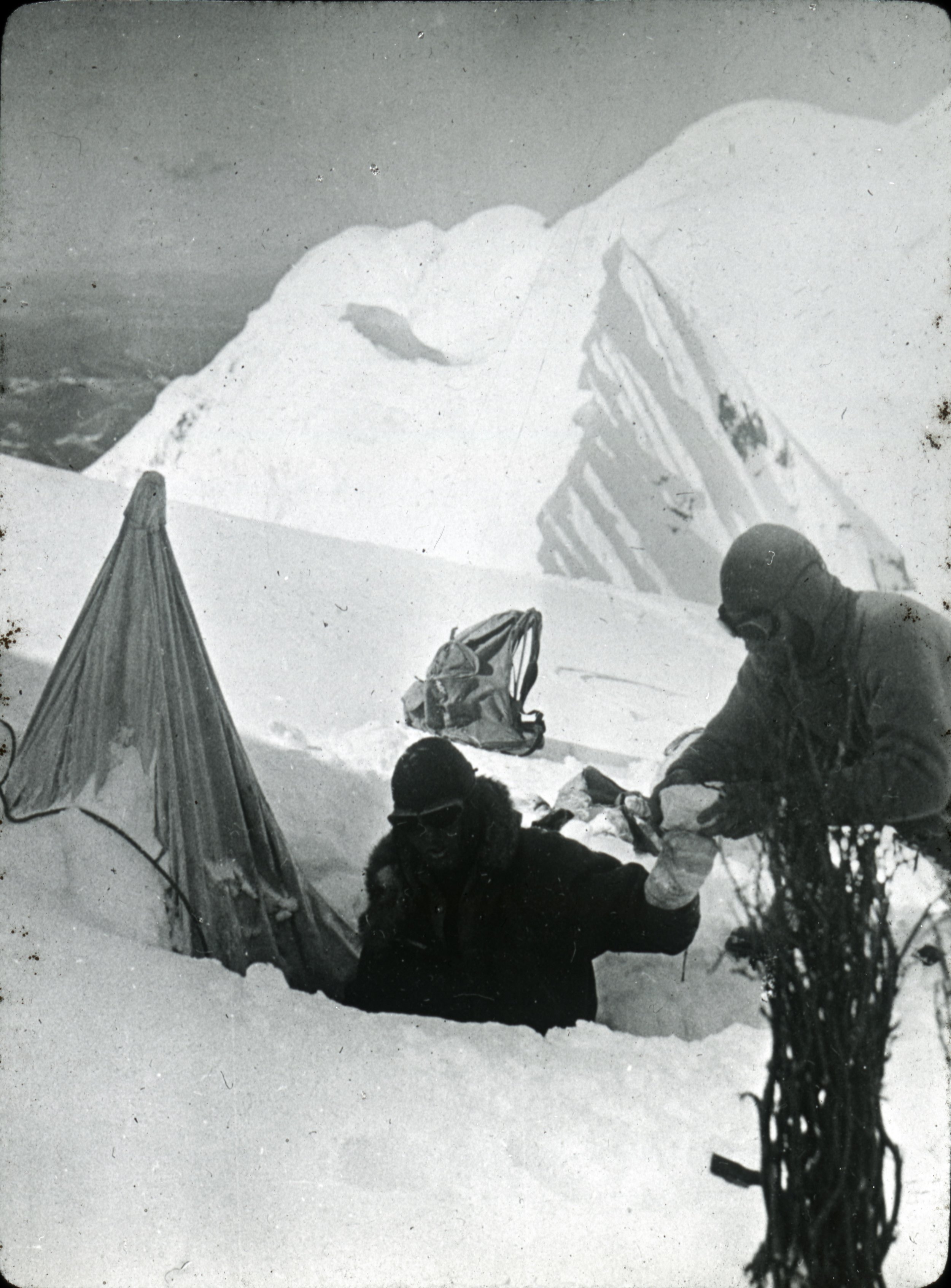

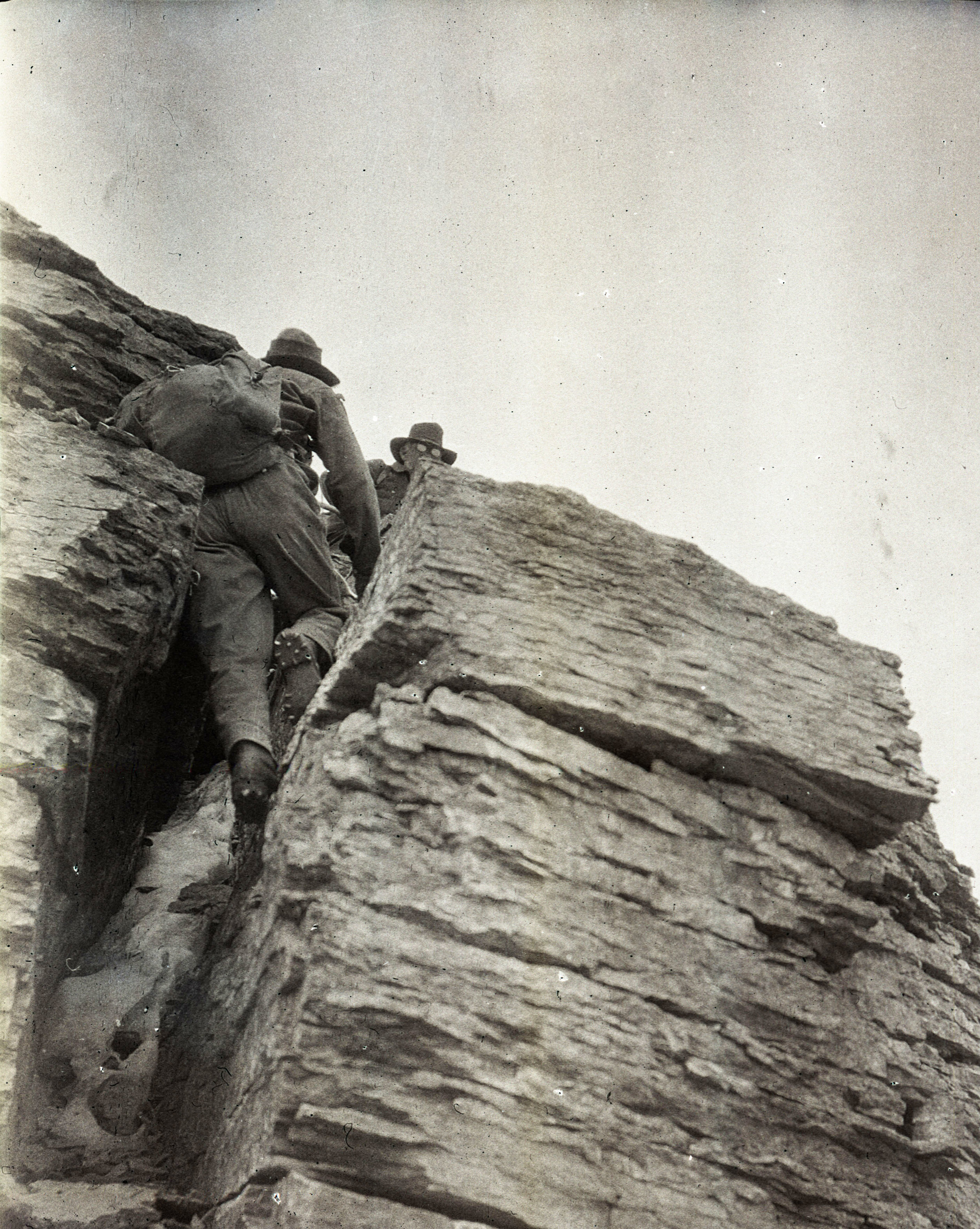

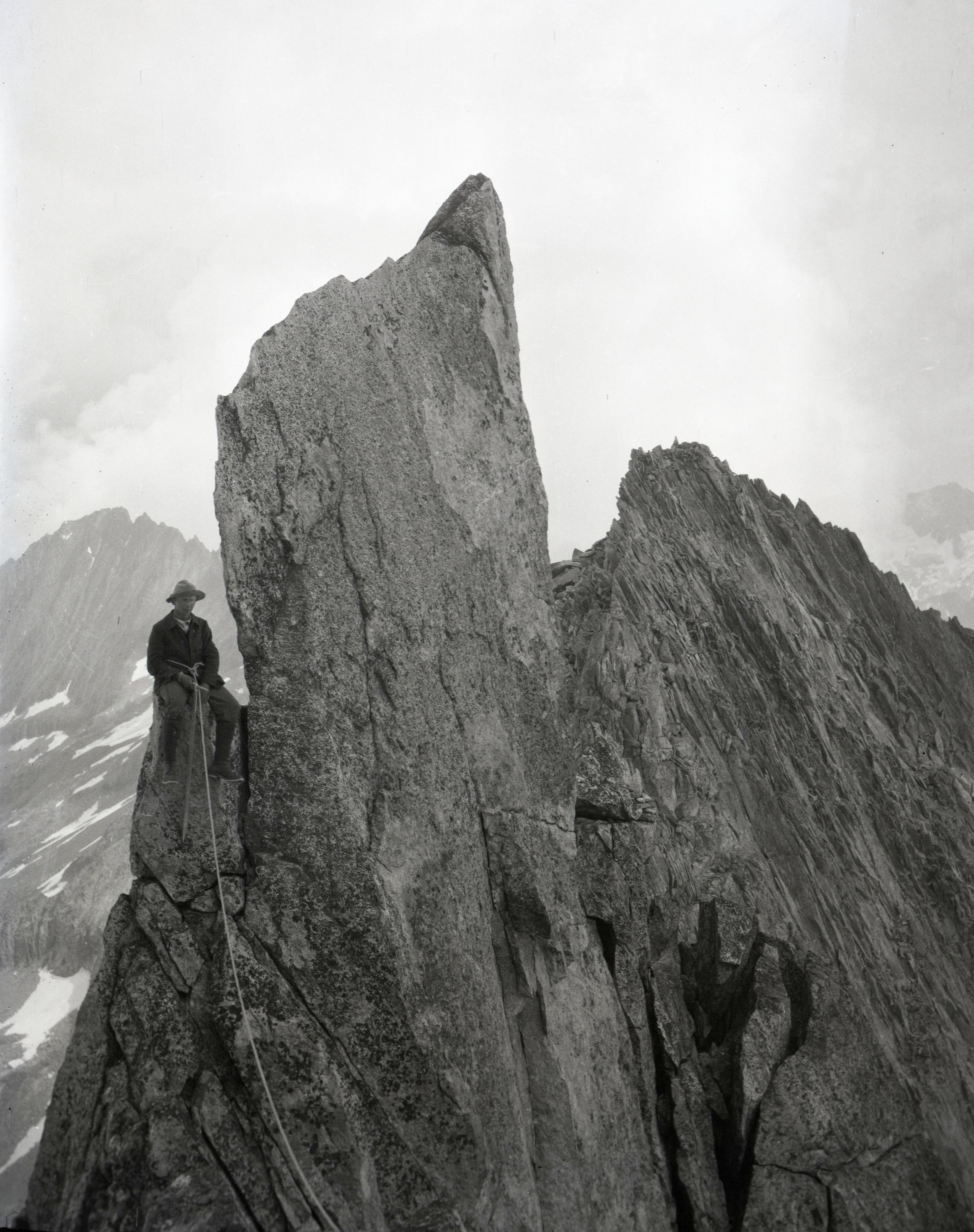

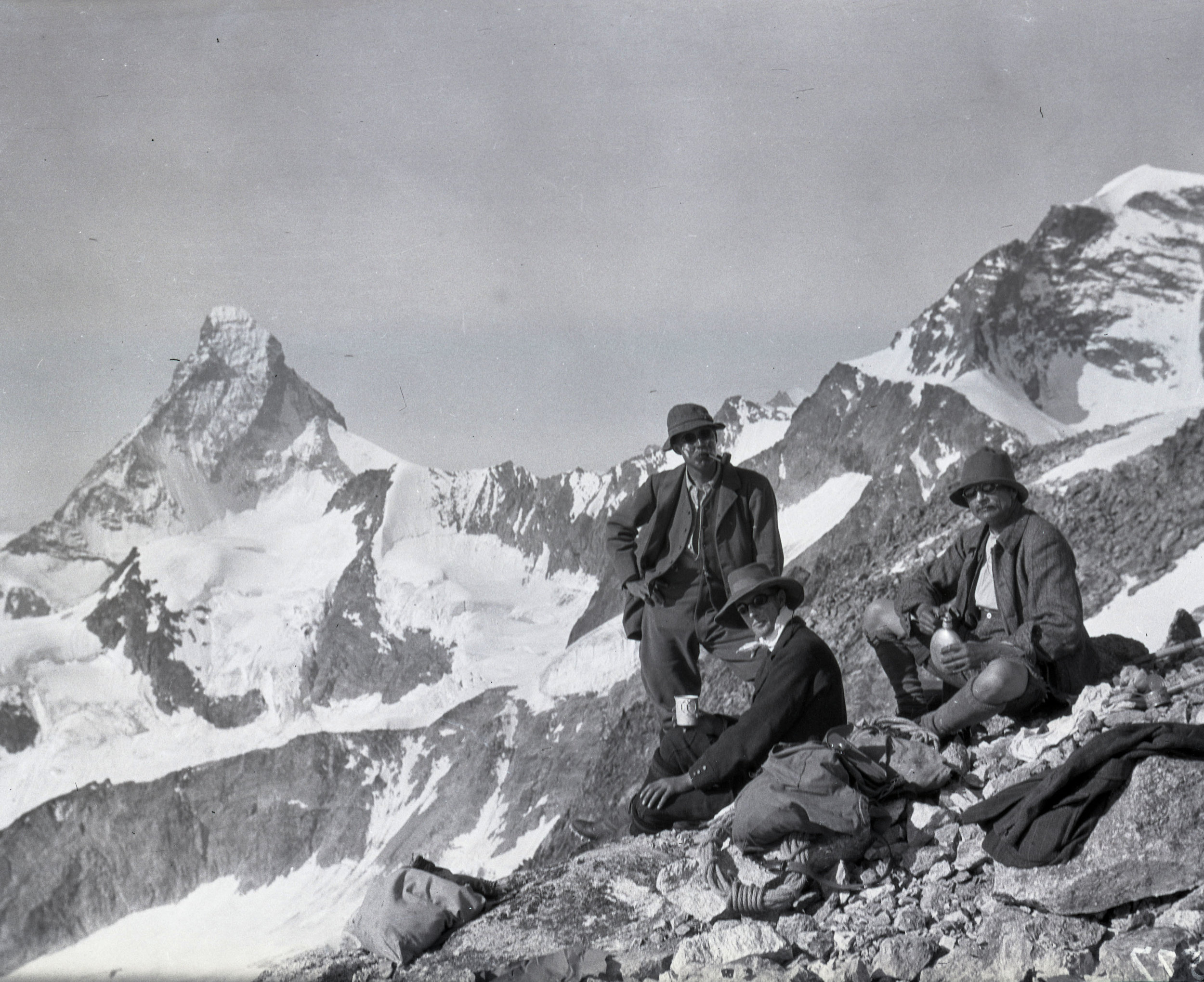

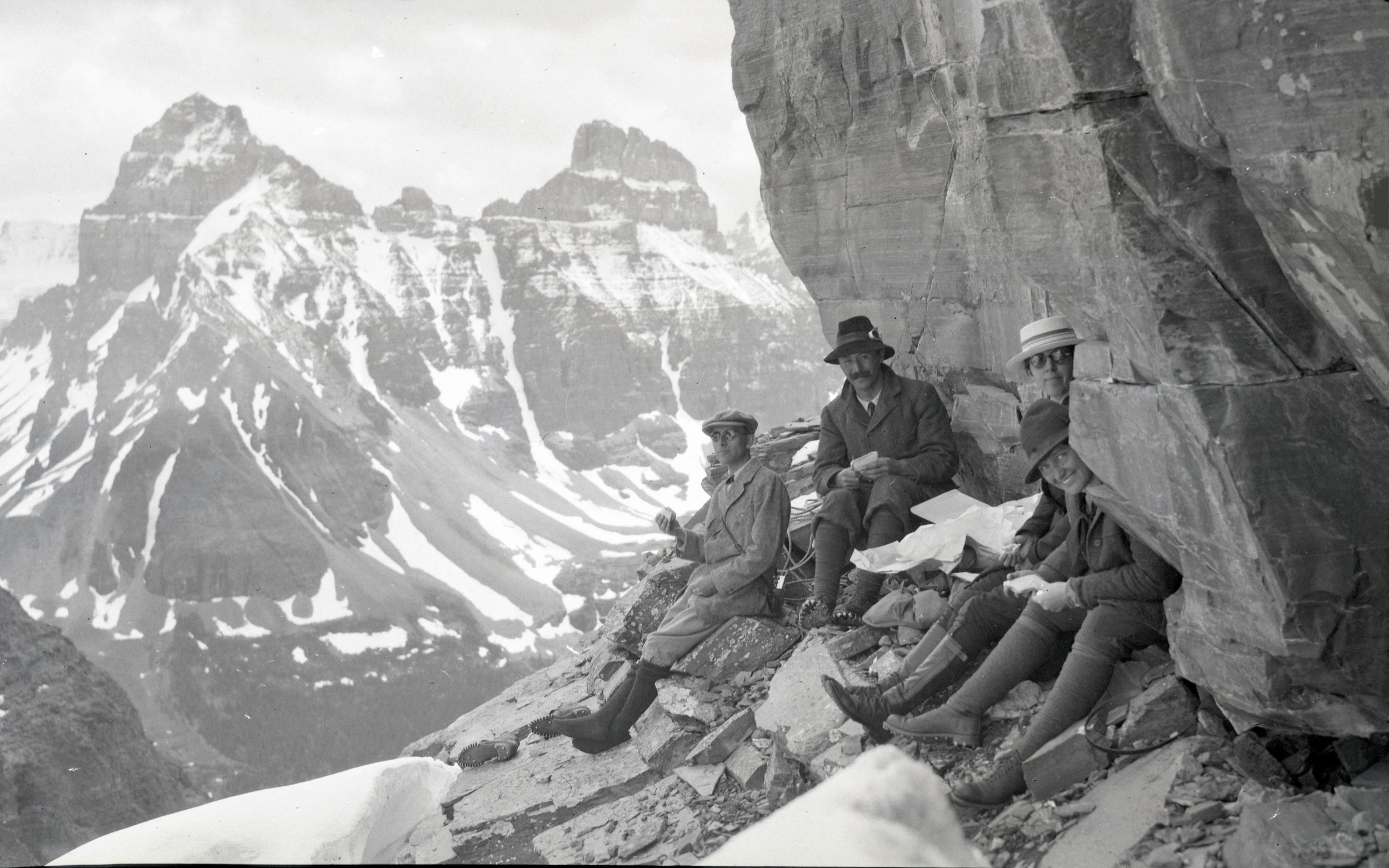

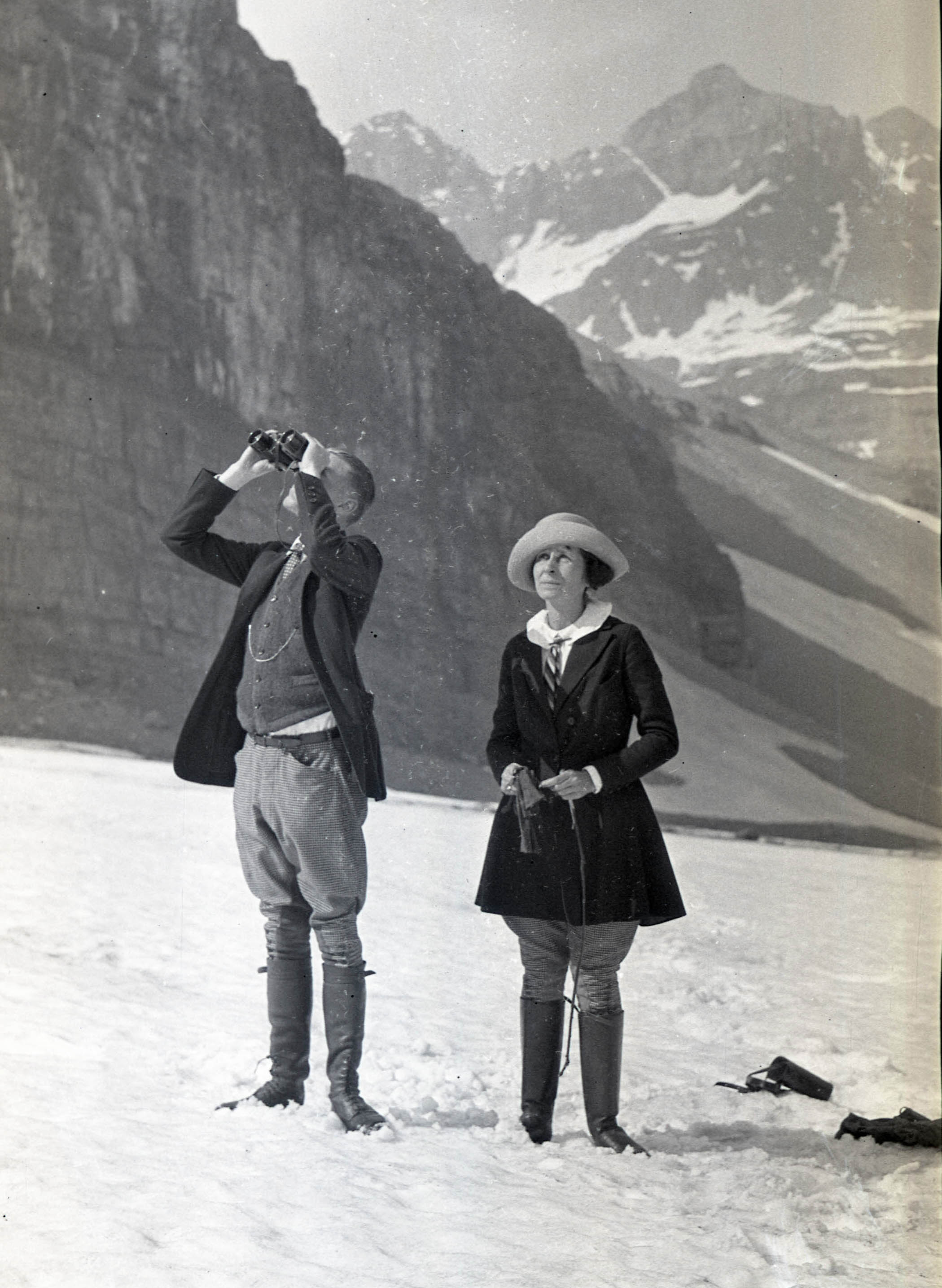

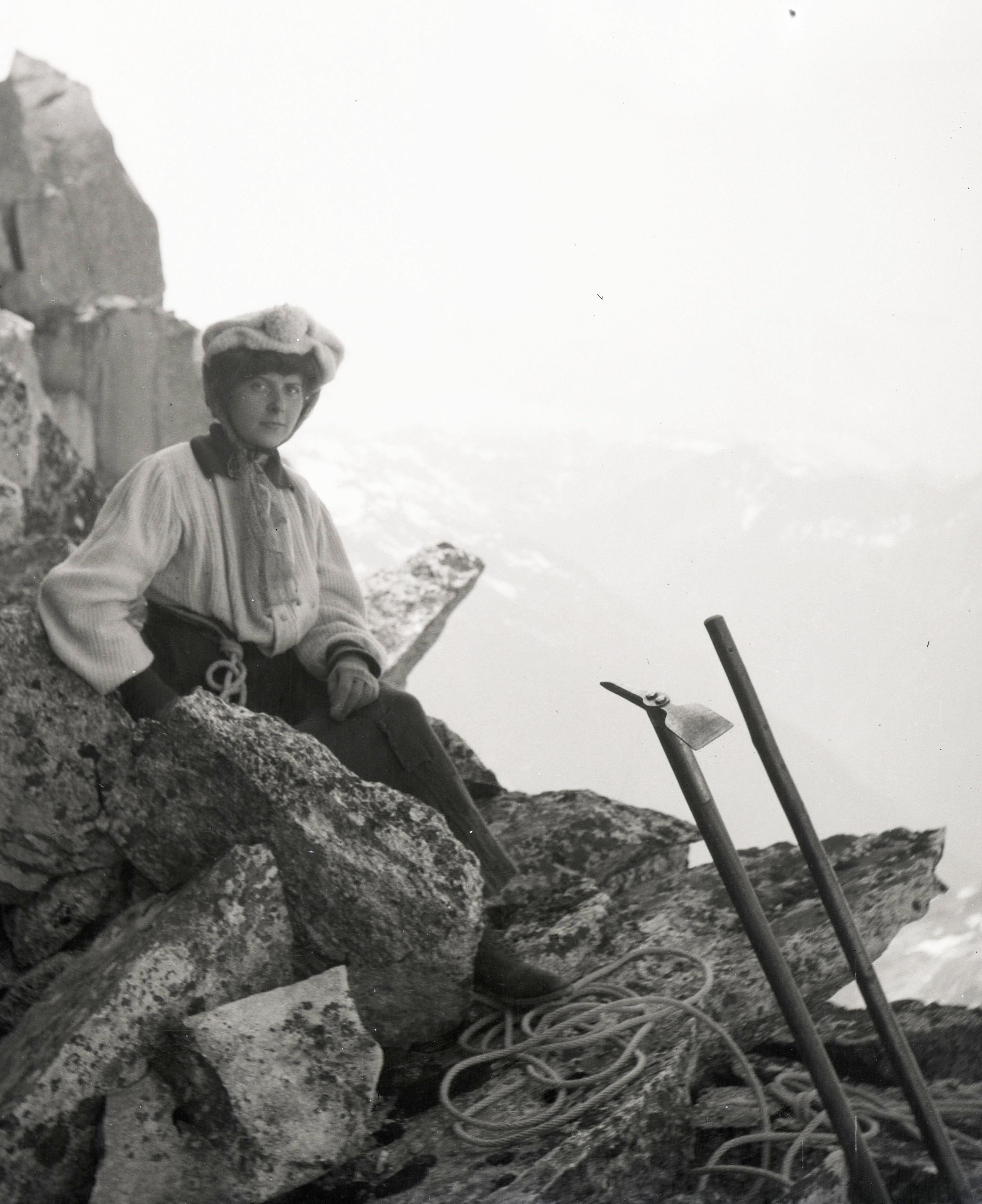

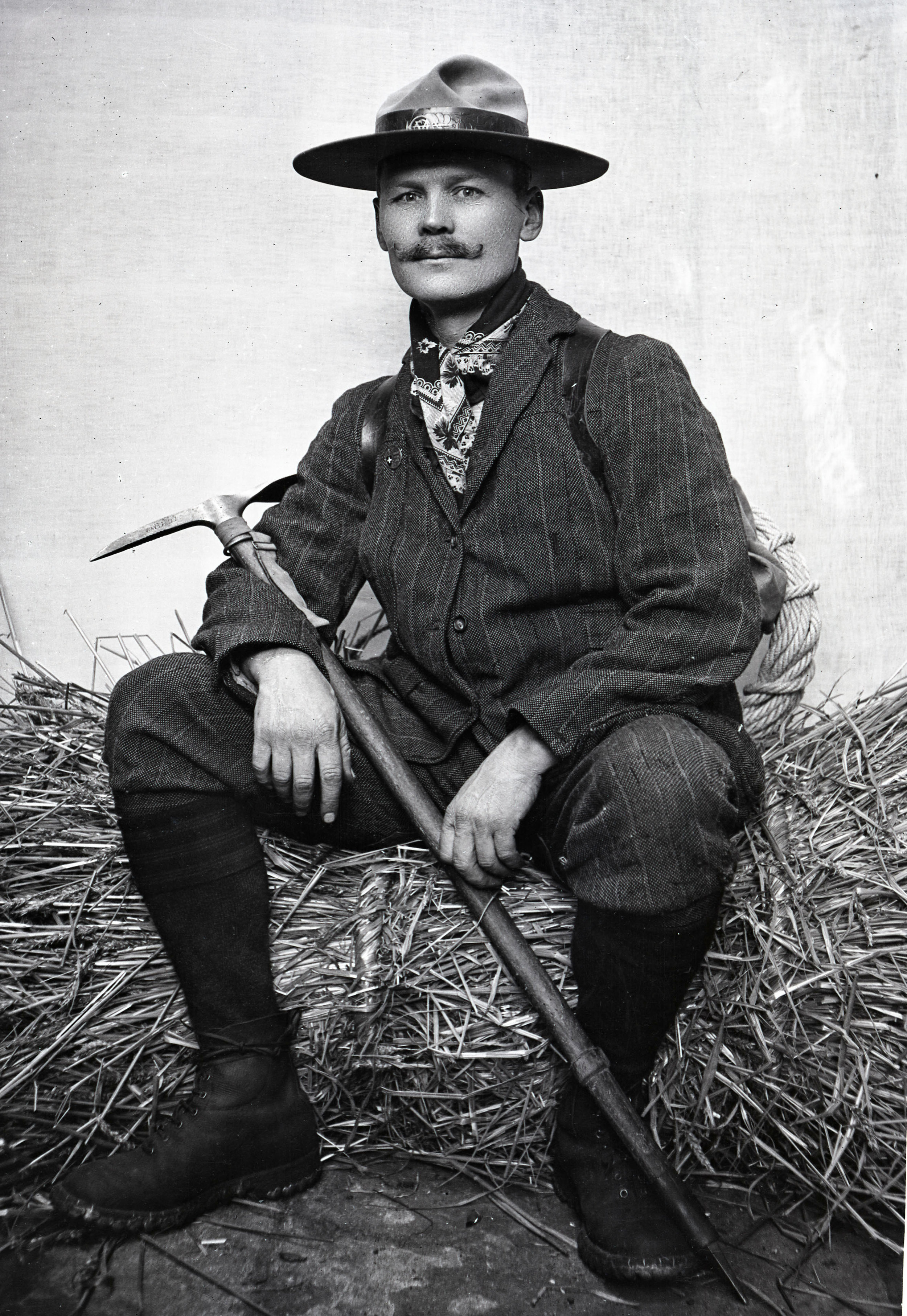

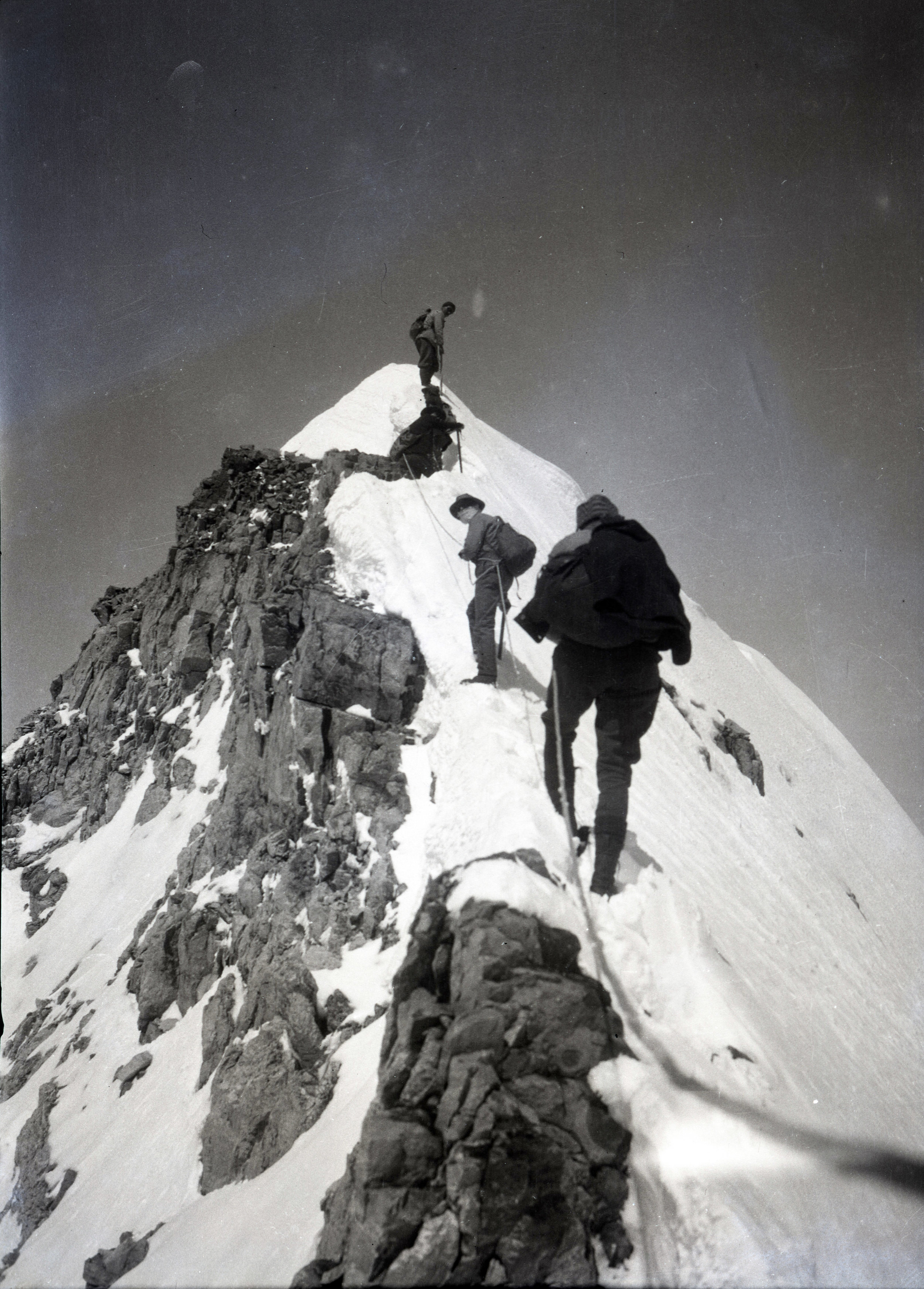

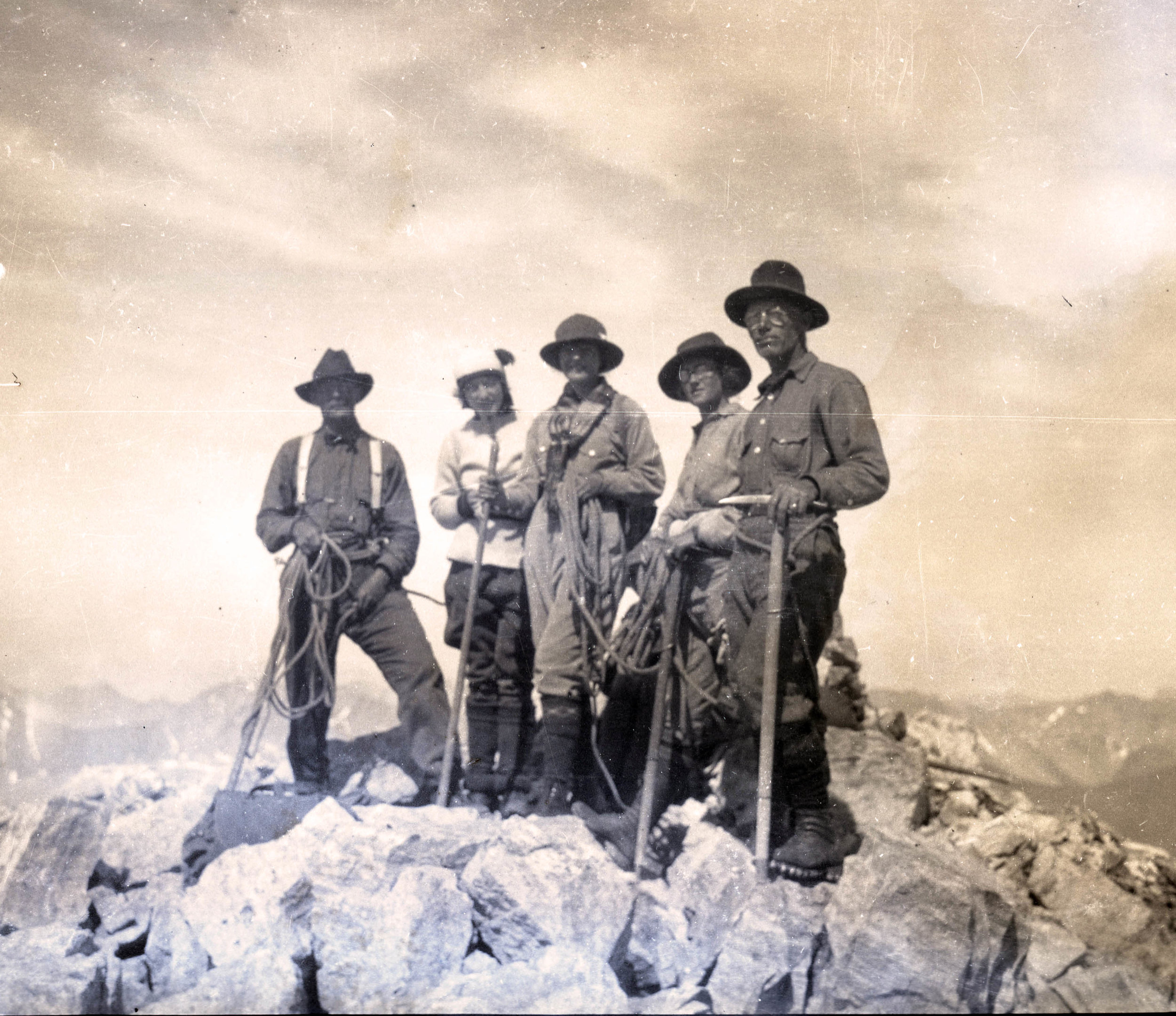

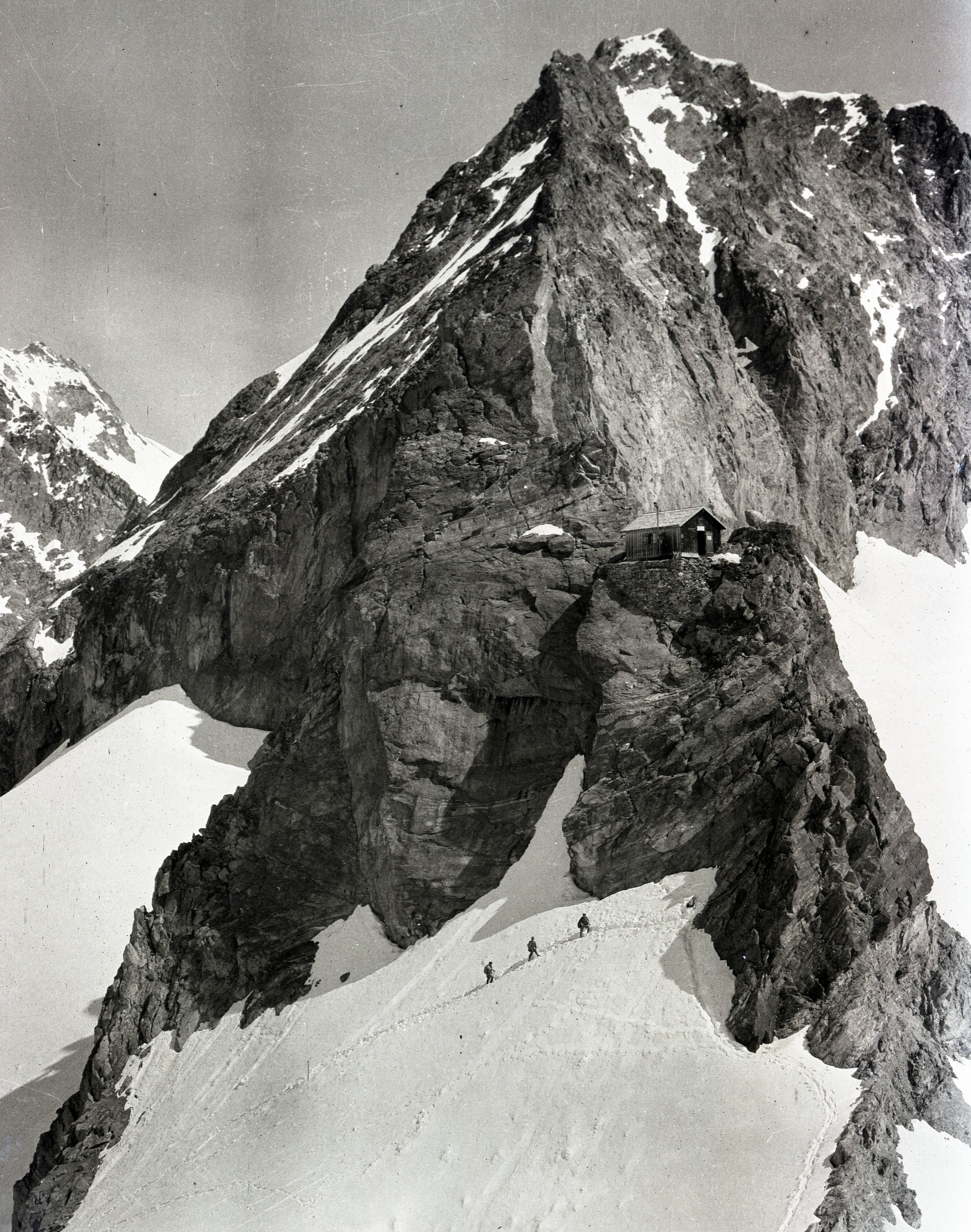

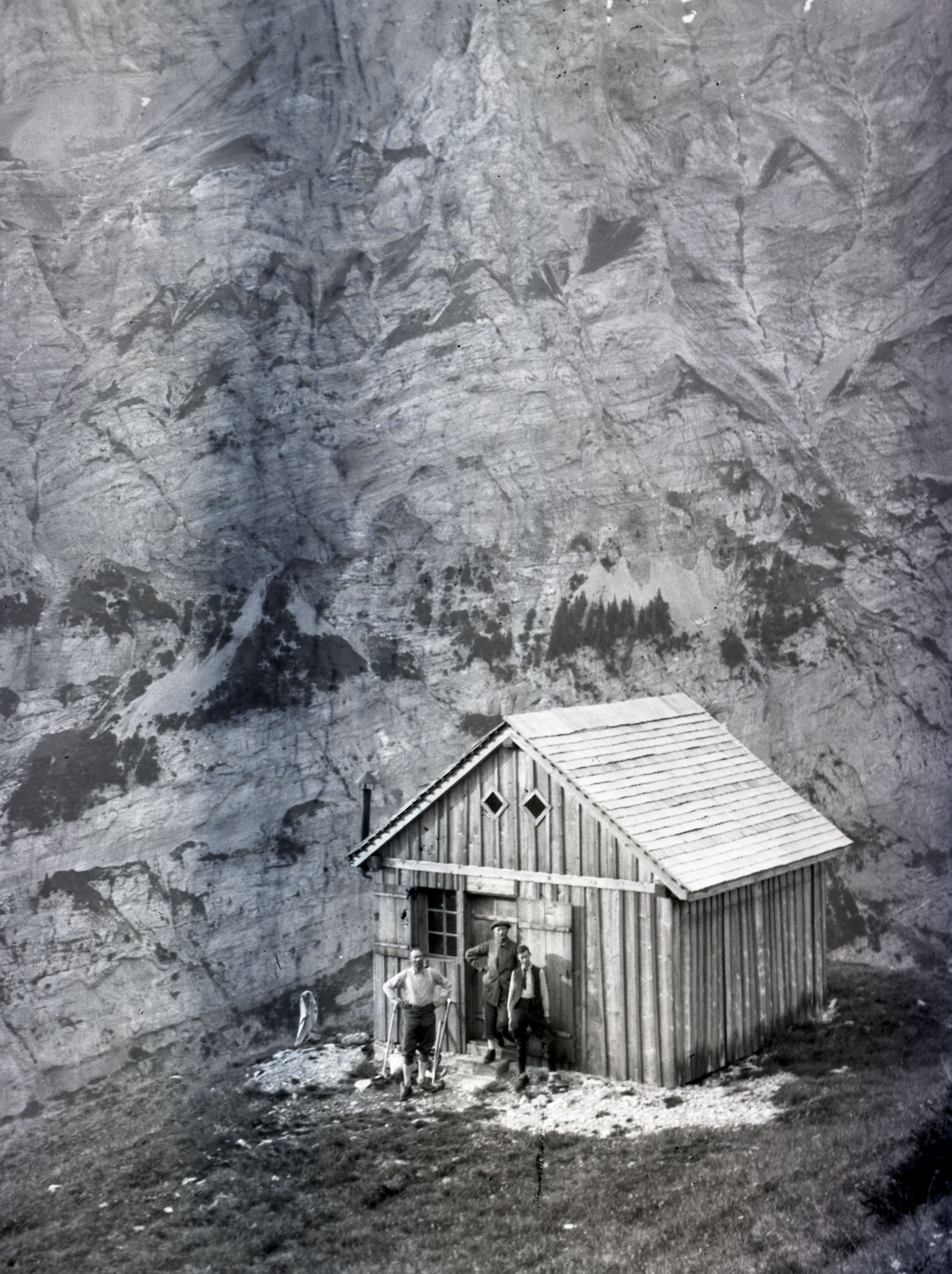

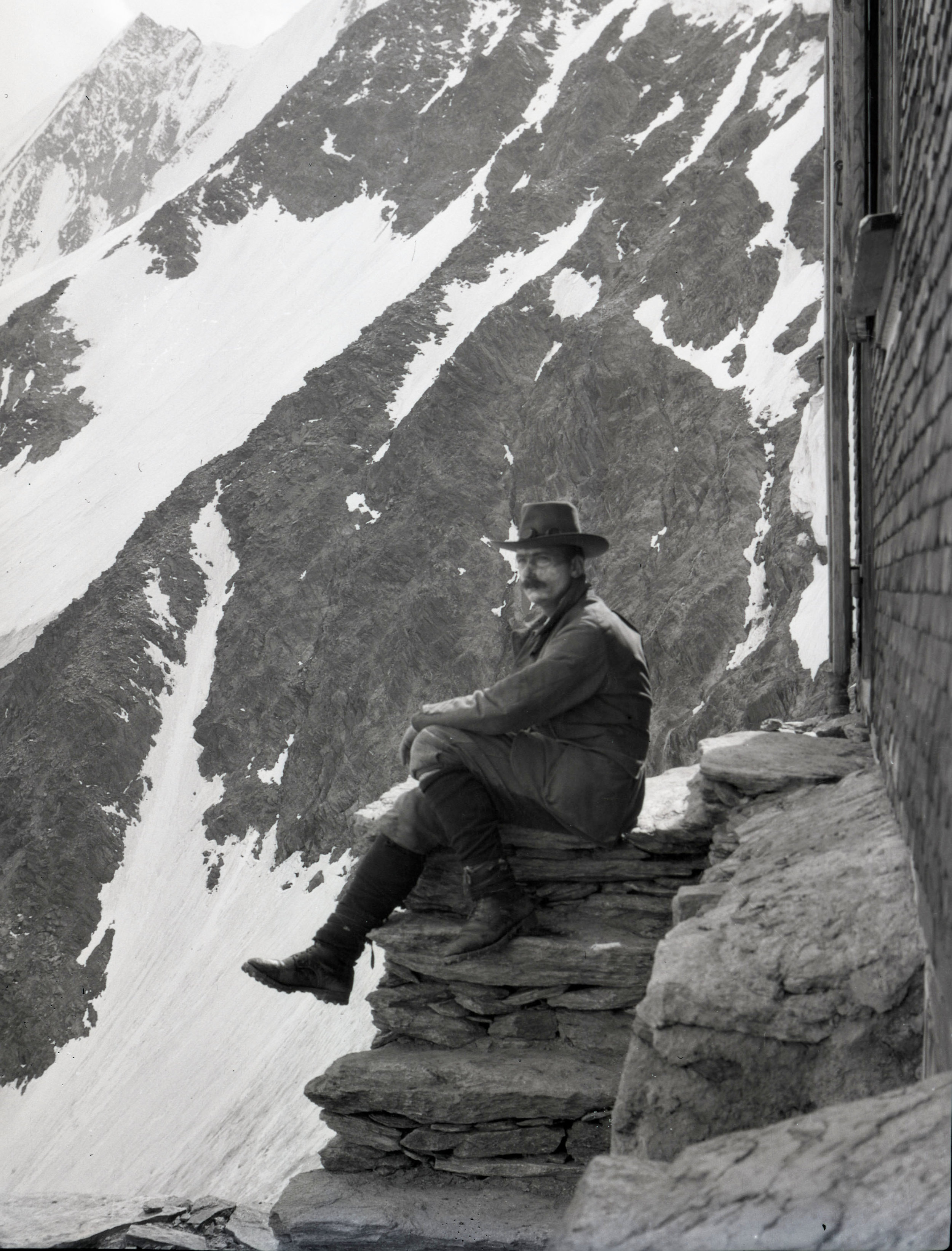

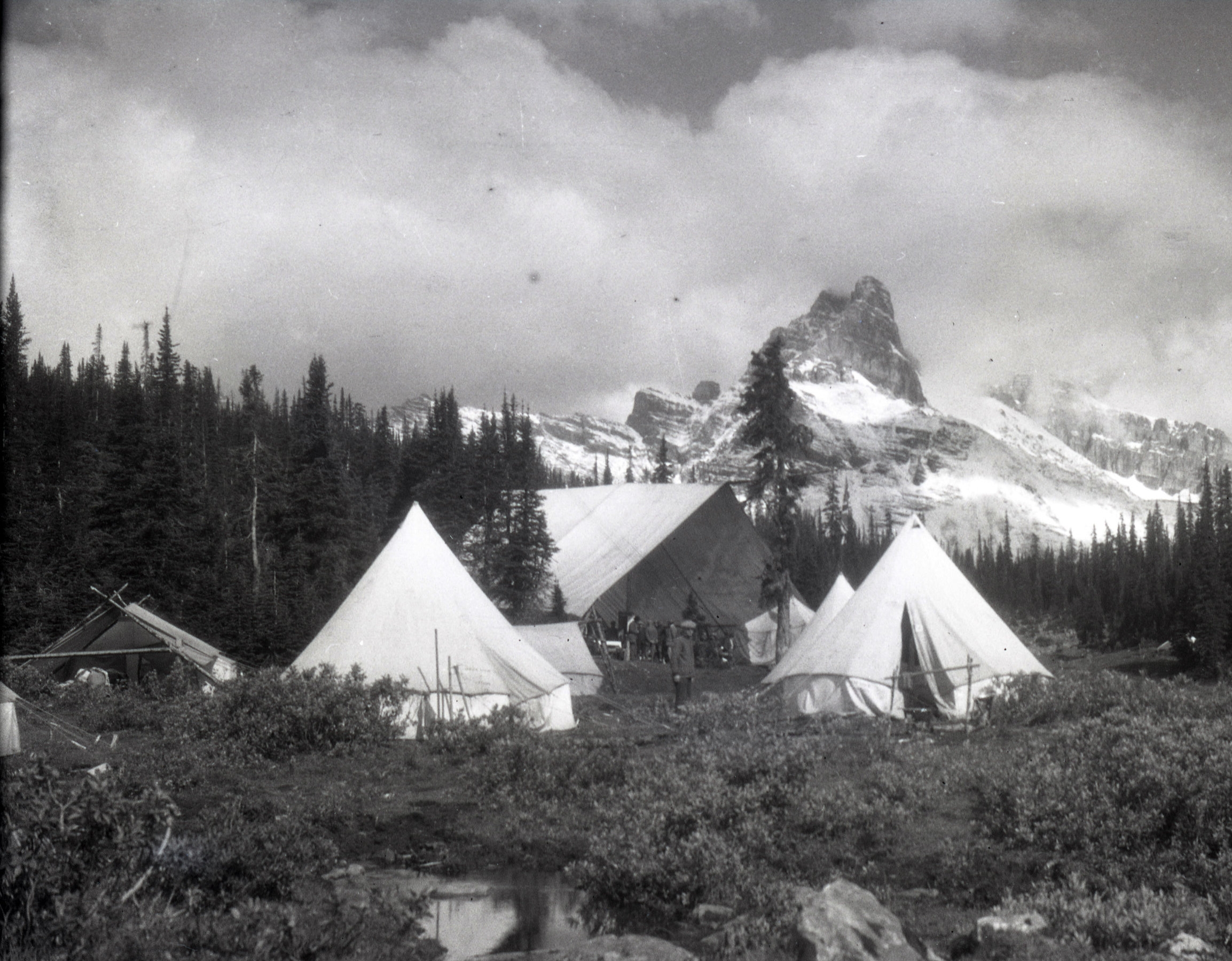

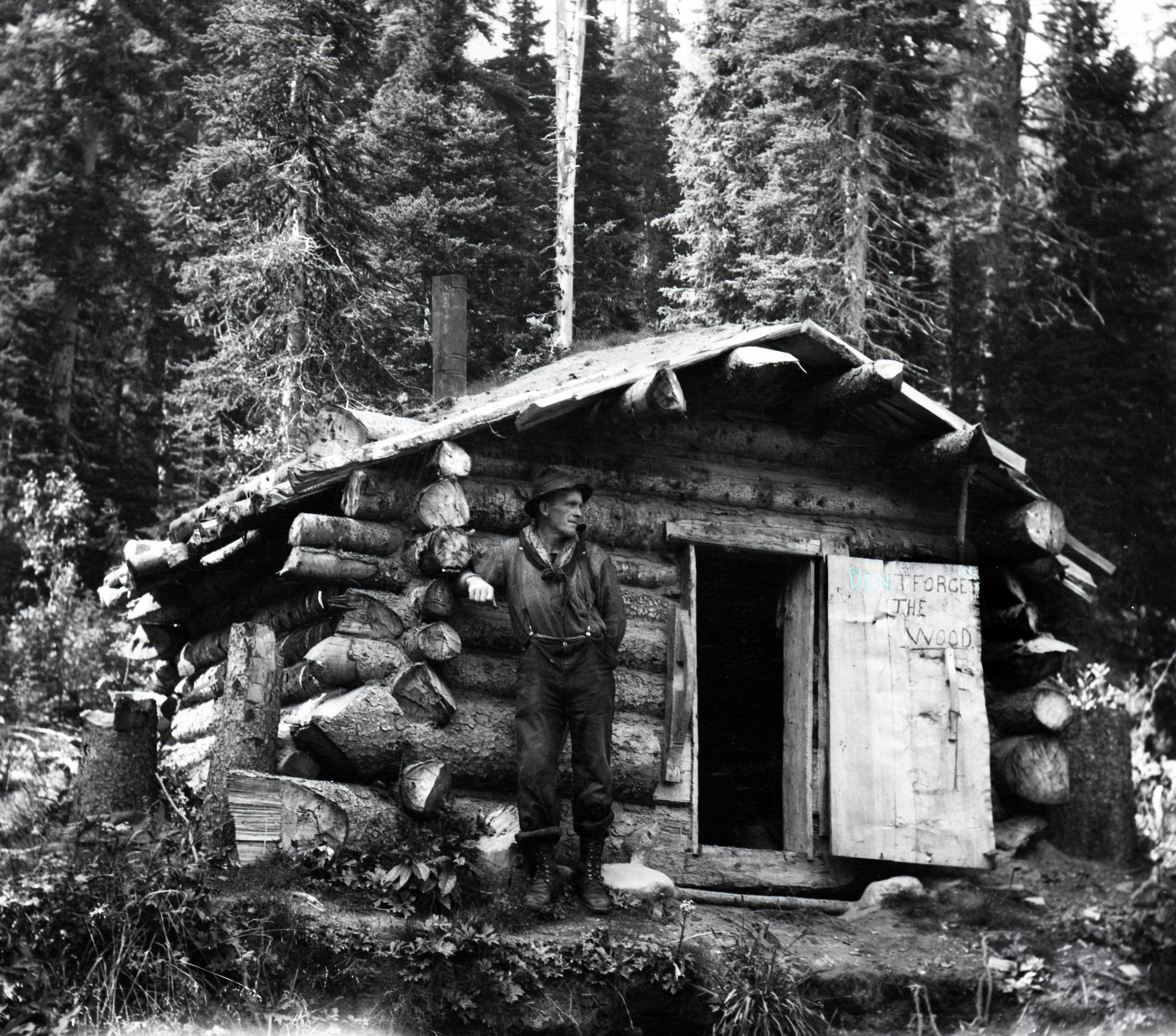

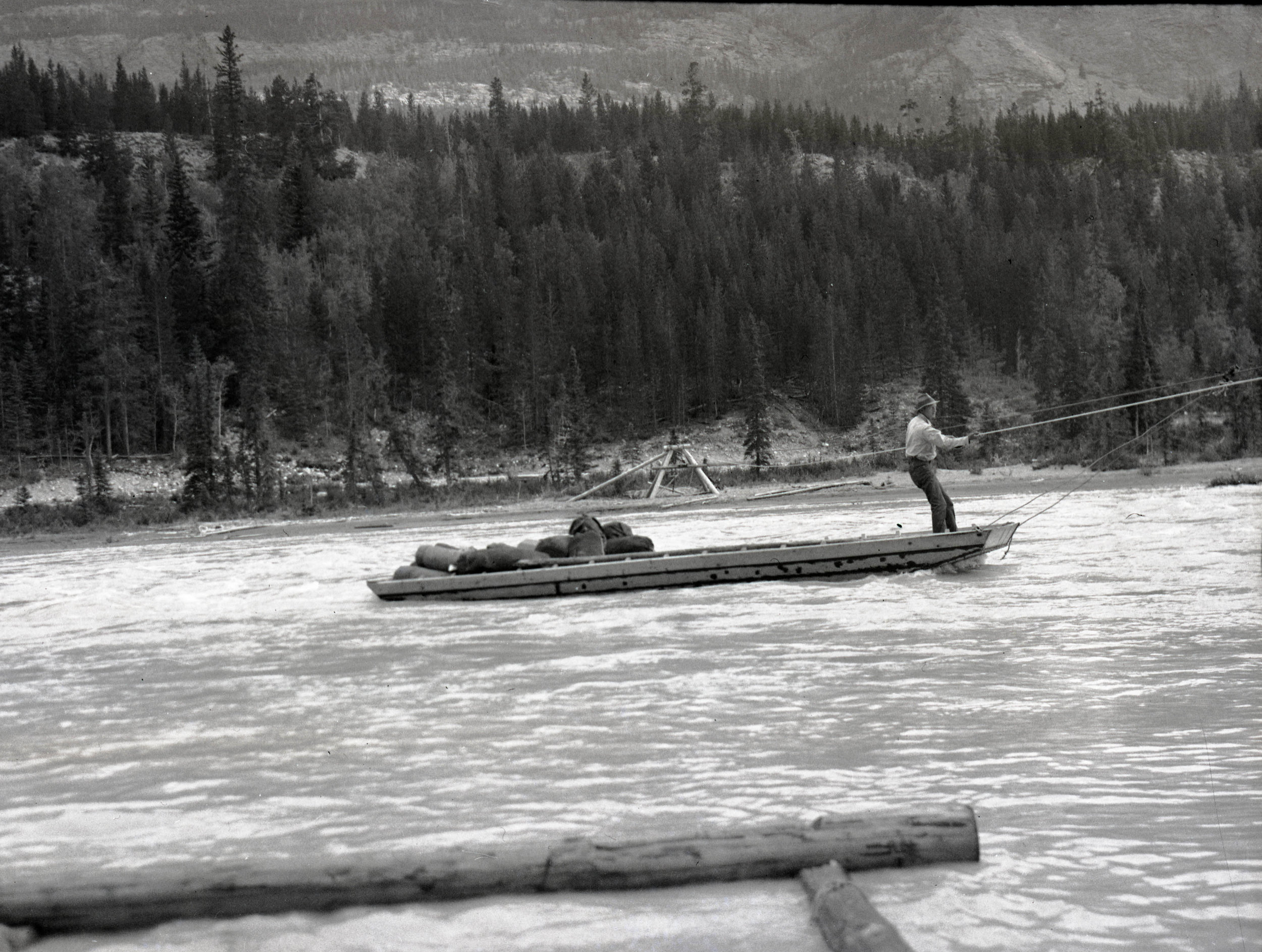

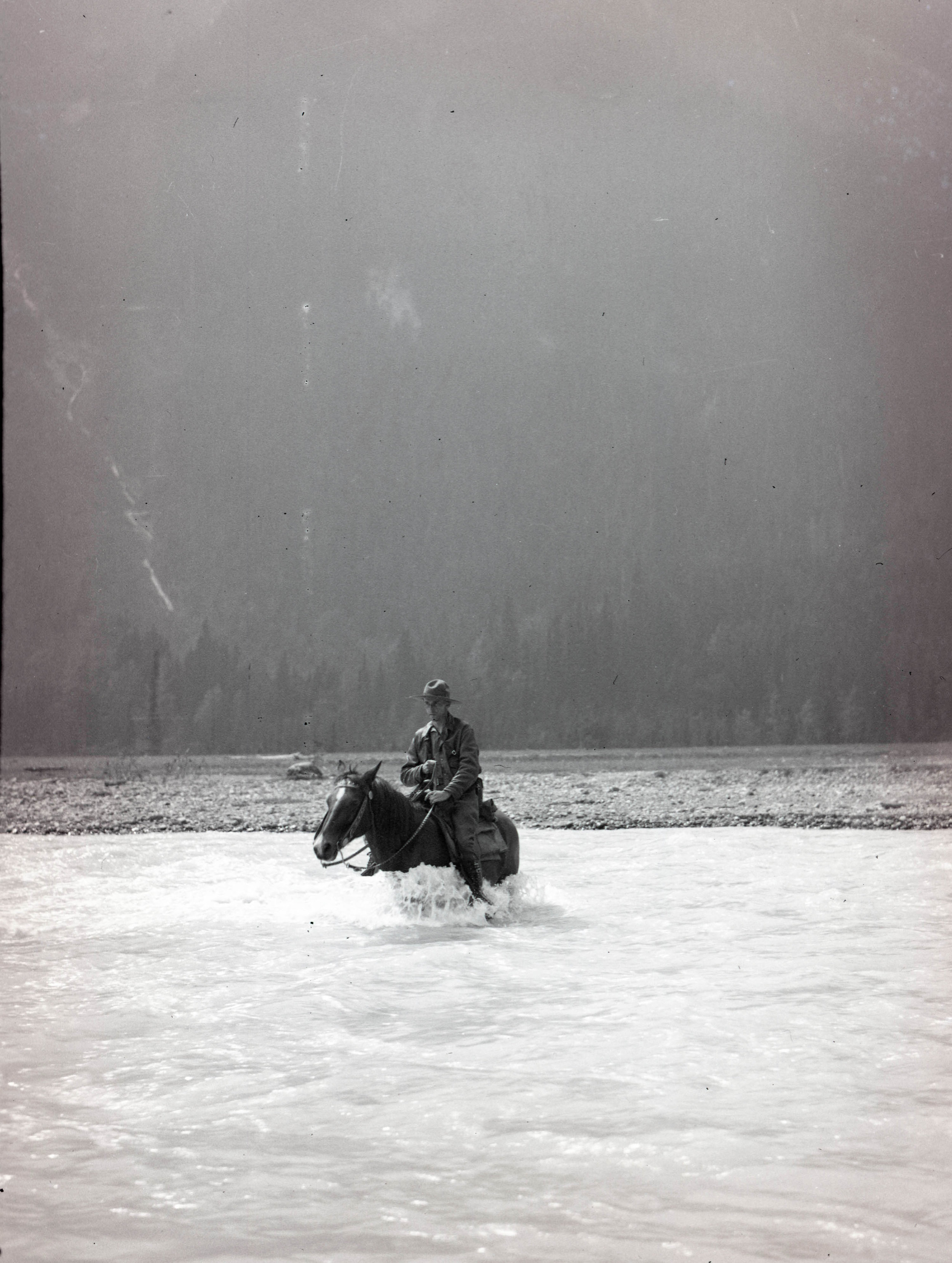

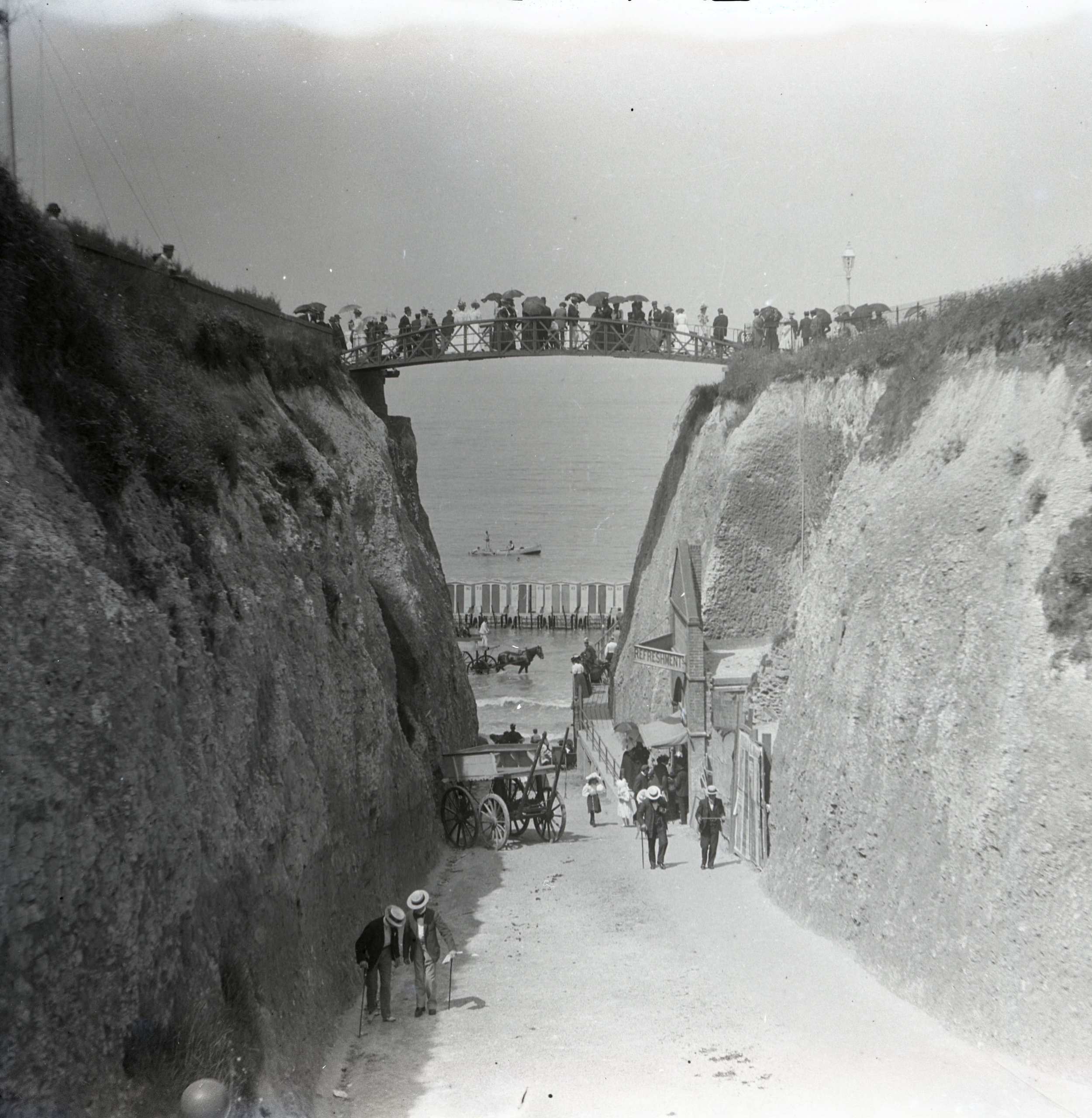

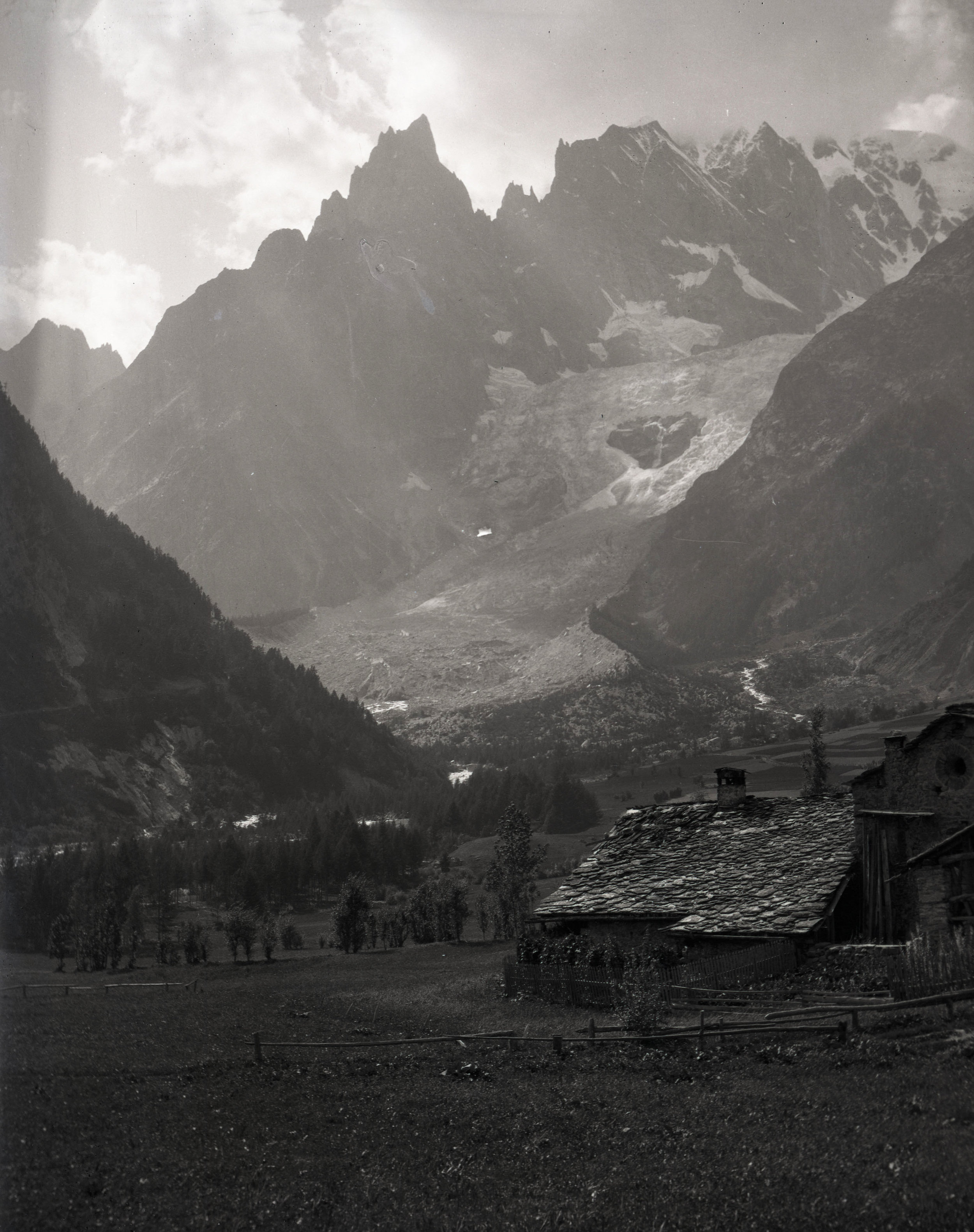

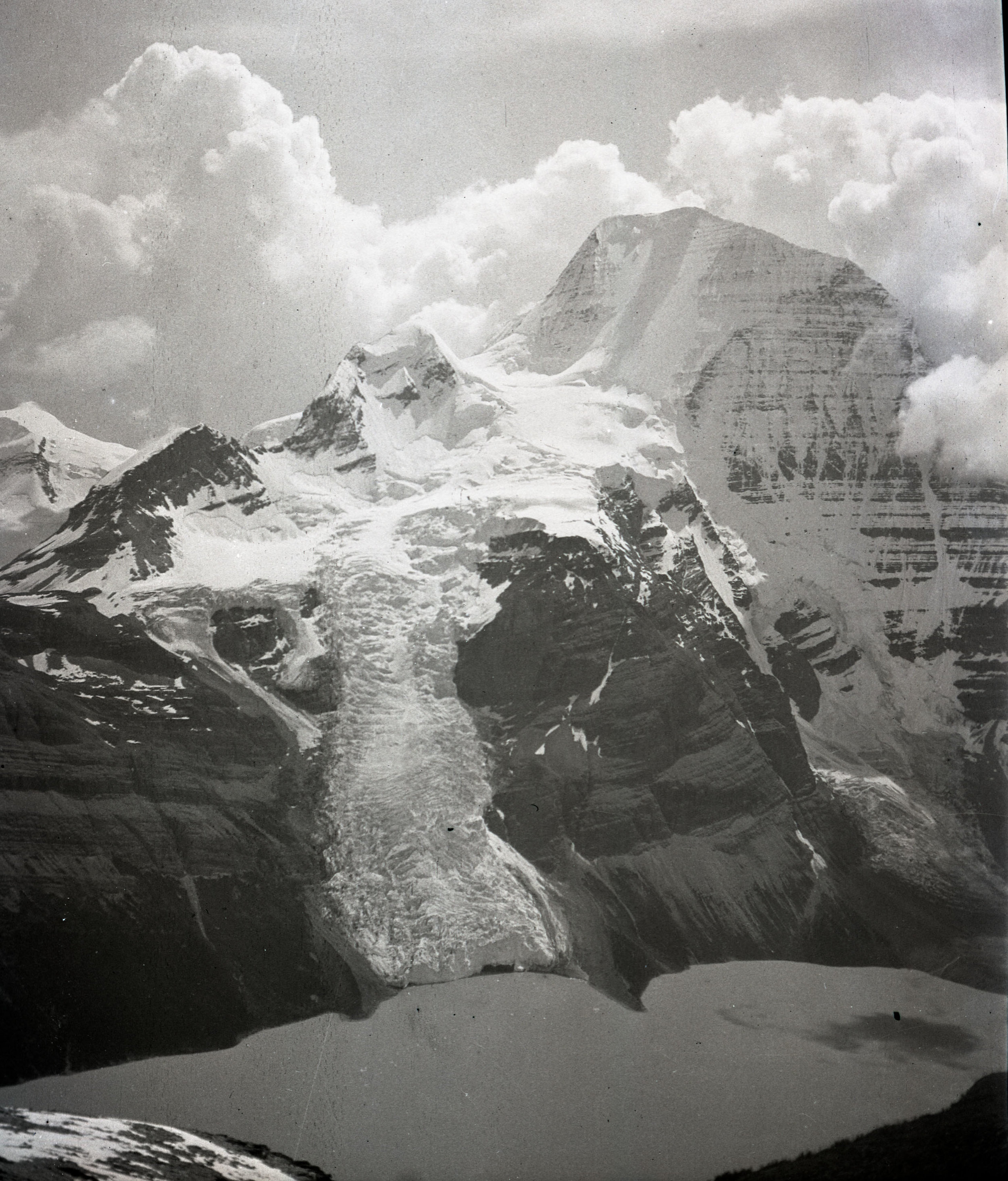

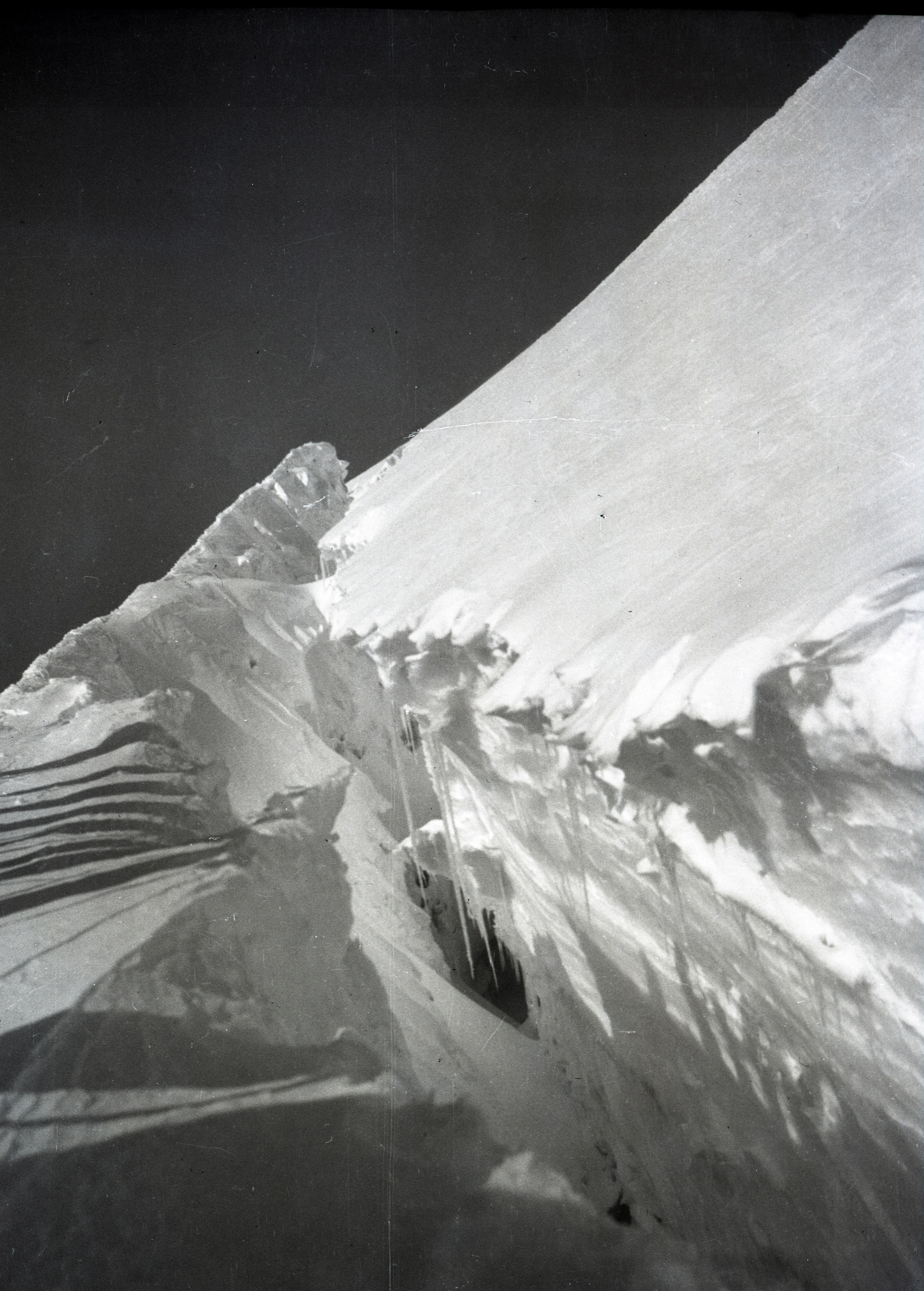

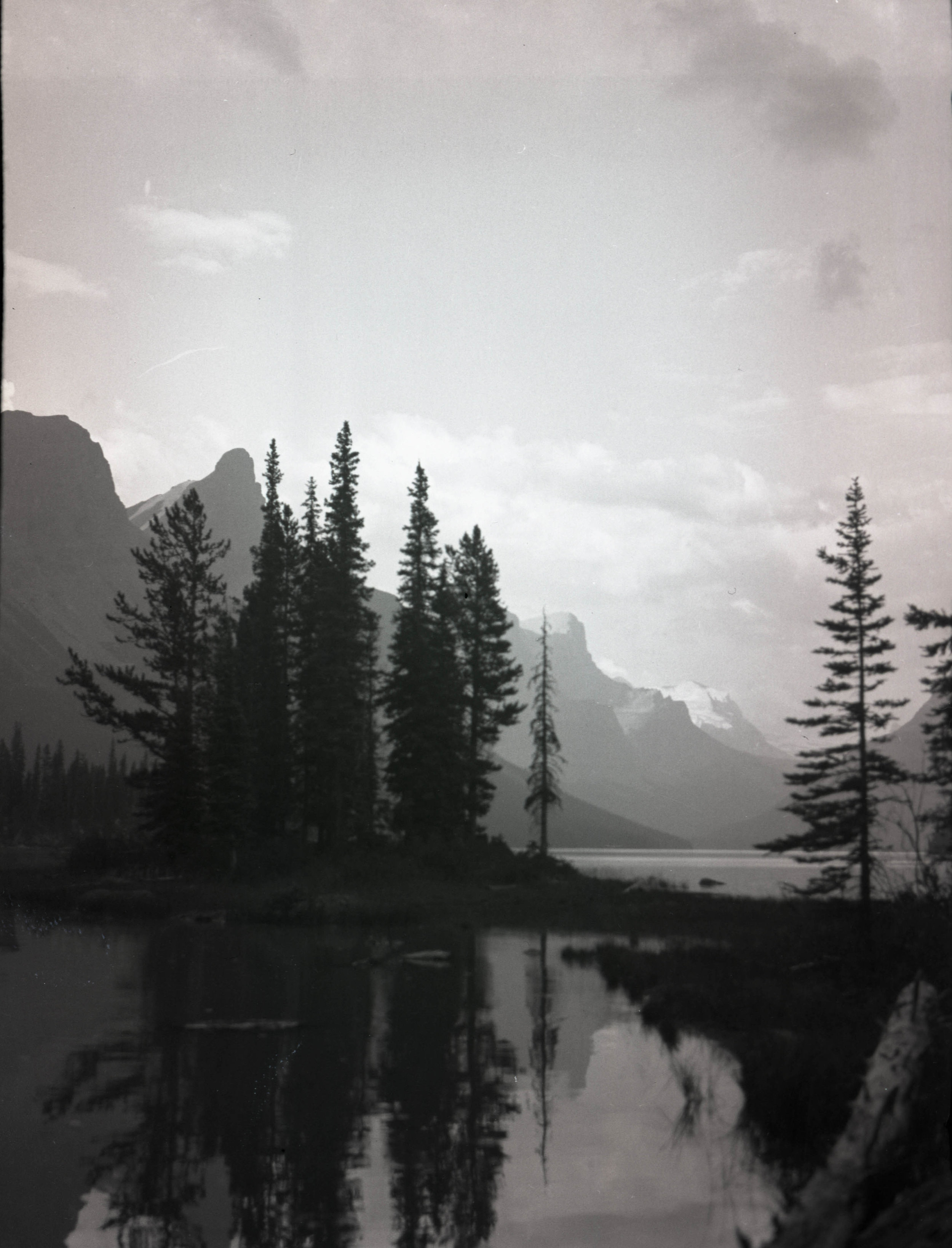

At the American Alpine Club Library, we’re very fortunate to have quite a few collections of photographs of climbing and mountaineering from the early 20th century. One of these, a collection of roughly 3000 photographic negatives dating from 1900 to about 1930, has been digitized in its entirety and made available to everyone.

It’s a great feeling to complete a project.

We’re excited to be able to increase access to this collection through digitization, which also reduces wear and tear on the original negatives and adds an additional layer of preservation.

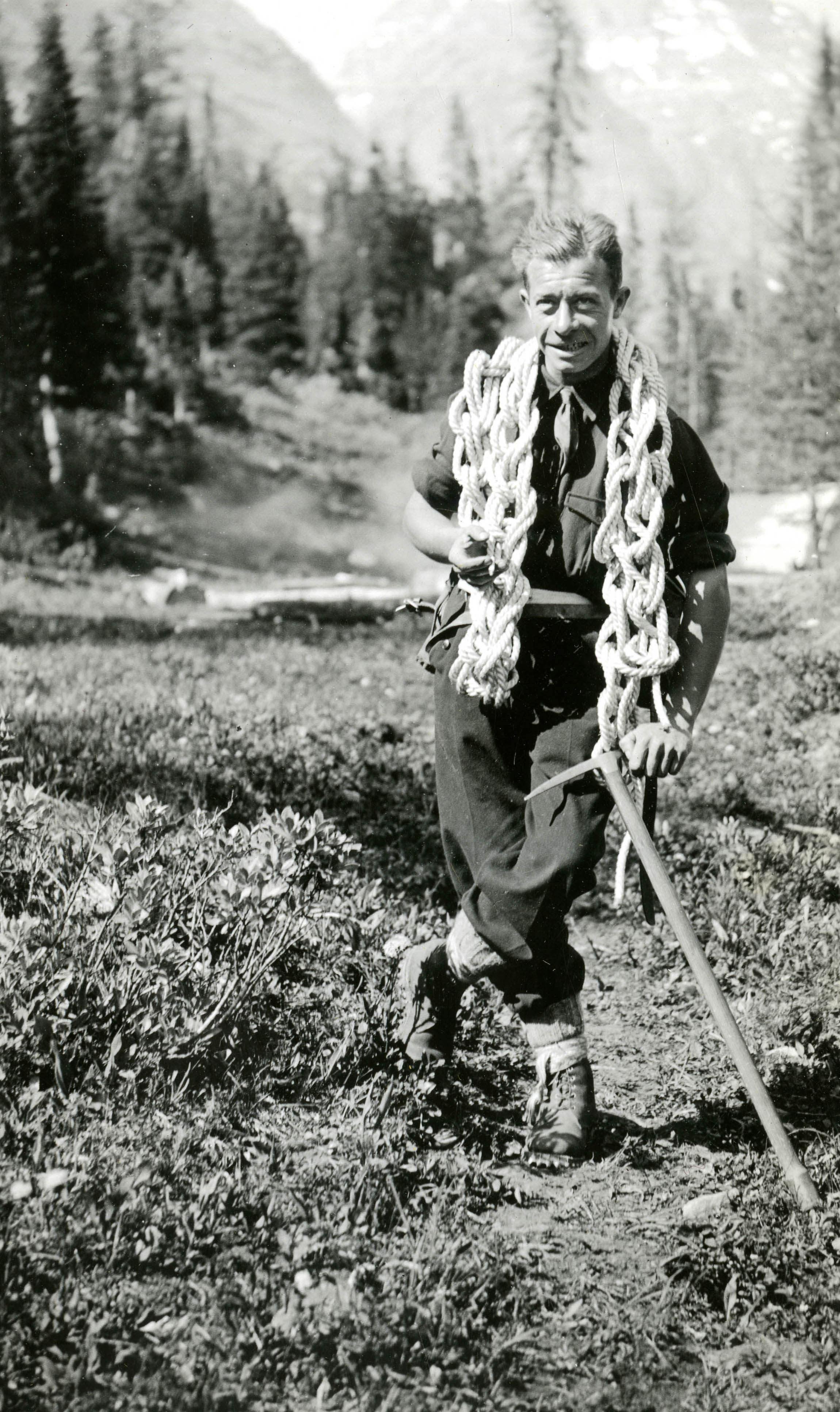

This collection of photos belonged to Andrew J. Gilmour, a dermatologist living and working in New York who was an avid climber and active member of the American Alpine Club during the 1920s and 1930s. He did a number of ascents in the Alps, the Canadian Rockies, the Cascades and the Western U.S., as well as Wales and the Lake District in the UK. His photos show us a lot about climbing at that time, the techniques, equipment, conditions and the people and places involved. It also provides us with a glimpse of what the world was like about 100 years ago.

We’ve gathered some of our favorite images from this collection in the slideshows below. Enjoy!

To see more of these images, check out our Andrew J. Gilmour album on Flickr.

Climbing and Mountaineering

Photos of climbing parties and mountaineering expeditions from about 1910 to the mid 1930’s.

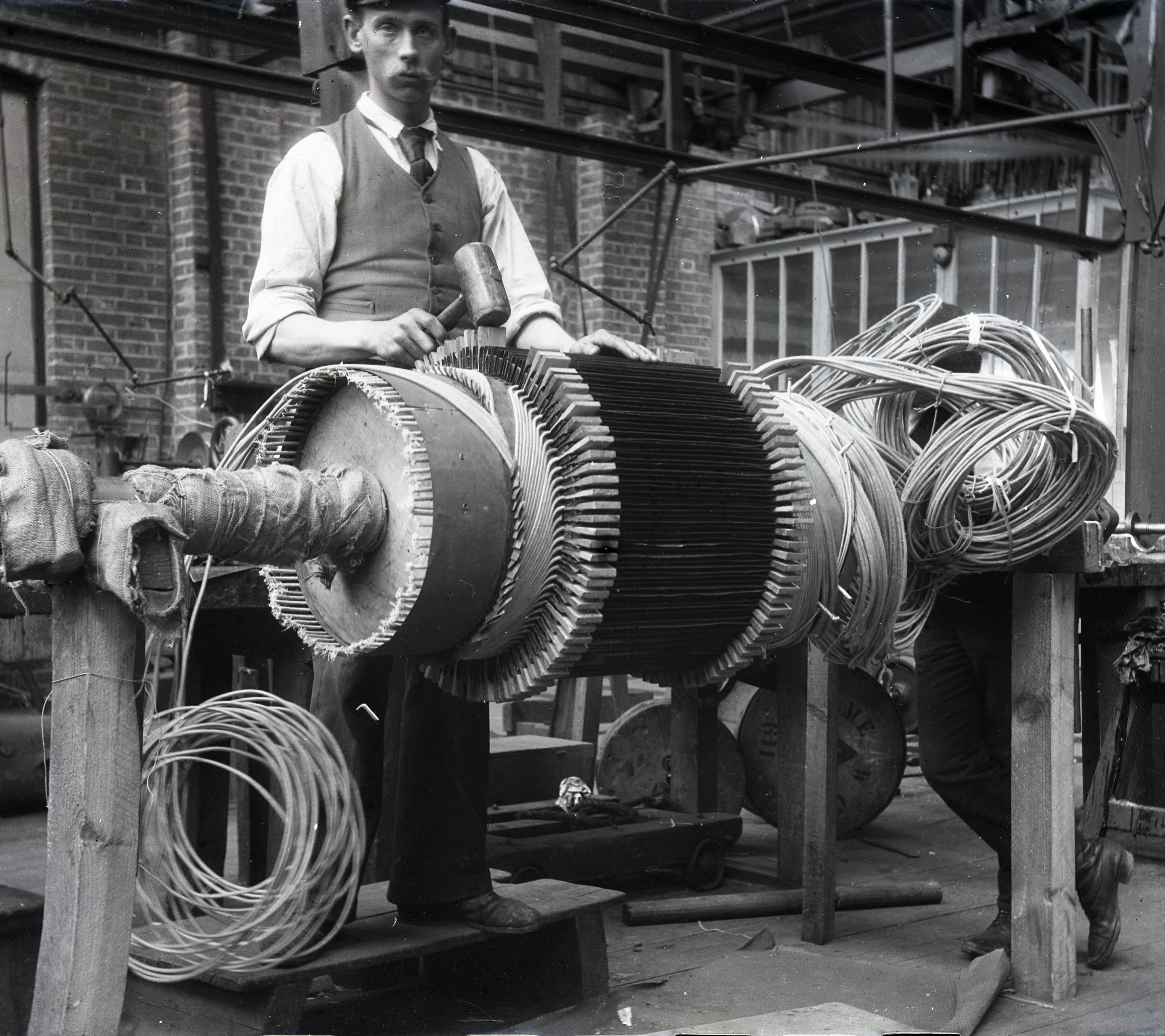

Equipment

Hobnail boots, hemp rope, canvas and silk tents and men’s and women’s climbing attire.

Summits

Men and women on top

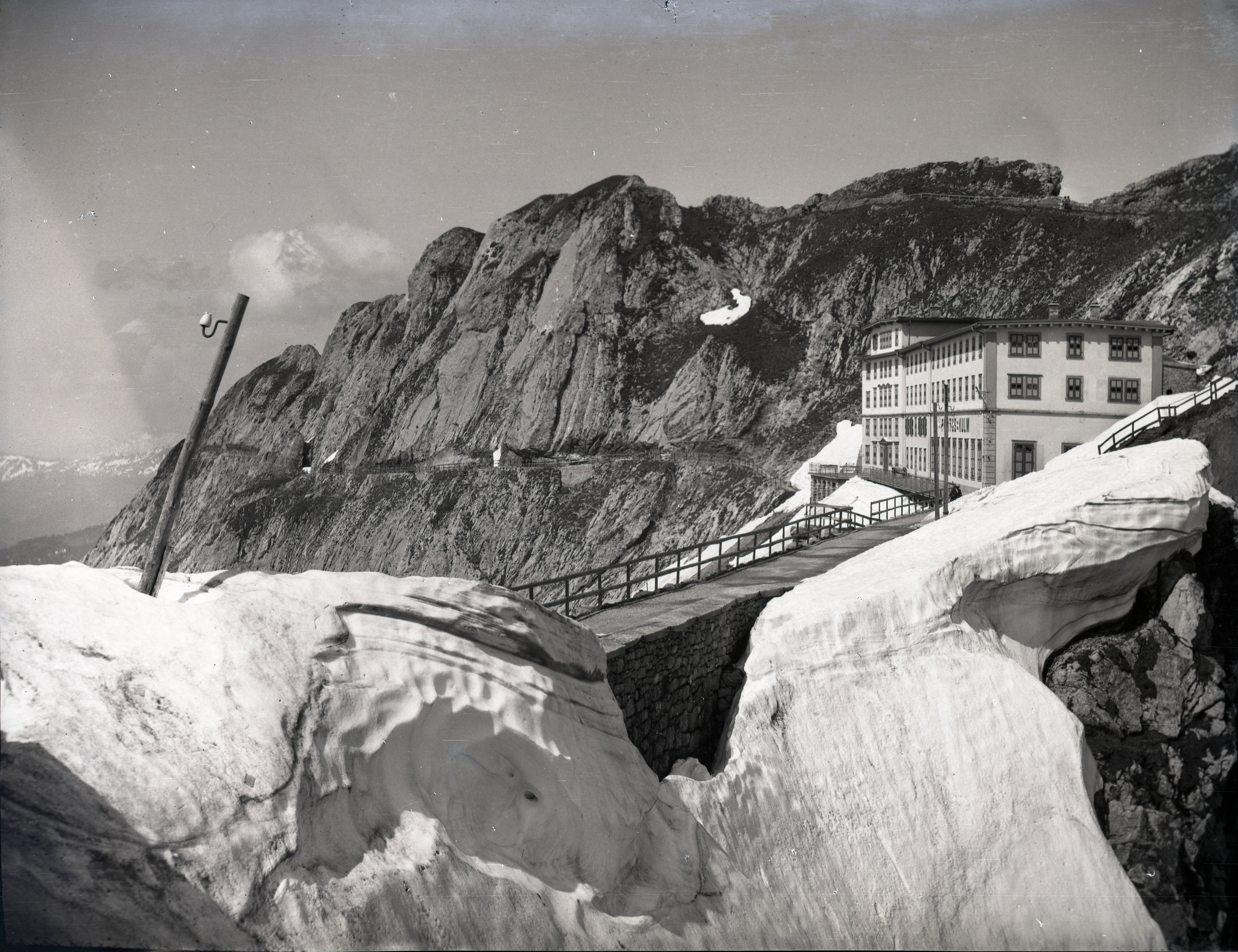

Camps and Huts

Huge camps for gatherings with the Alpine Club of Canada, tents and lean-tos in the woods, Swiss Alpine Club huts - many of which are still in use today.

Travel

It was harder in those days to get to some of these remote locations. There were far fewer roads, almost no highways and air travel was still in its infancy. Trains, ships and horses were commonly used.

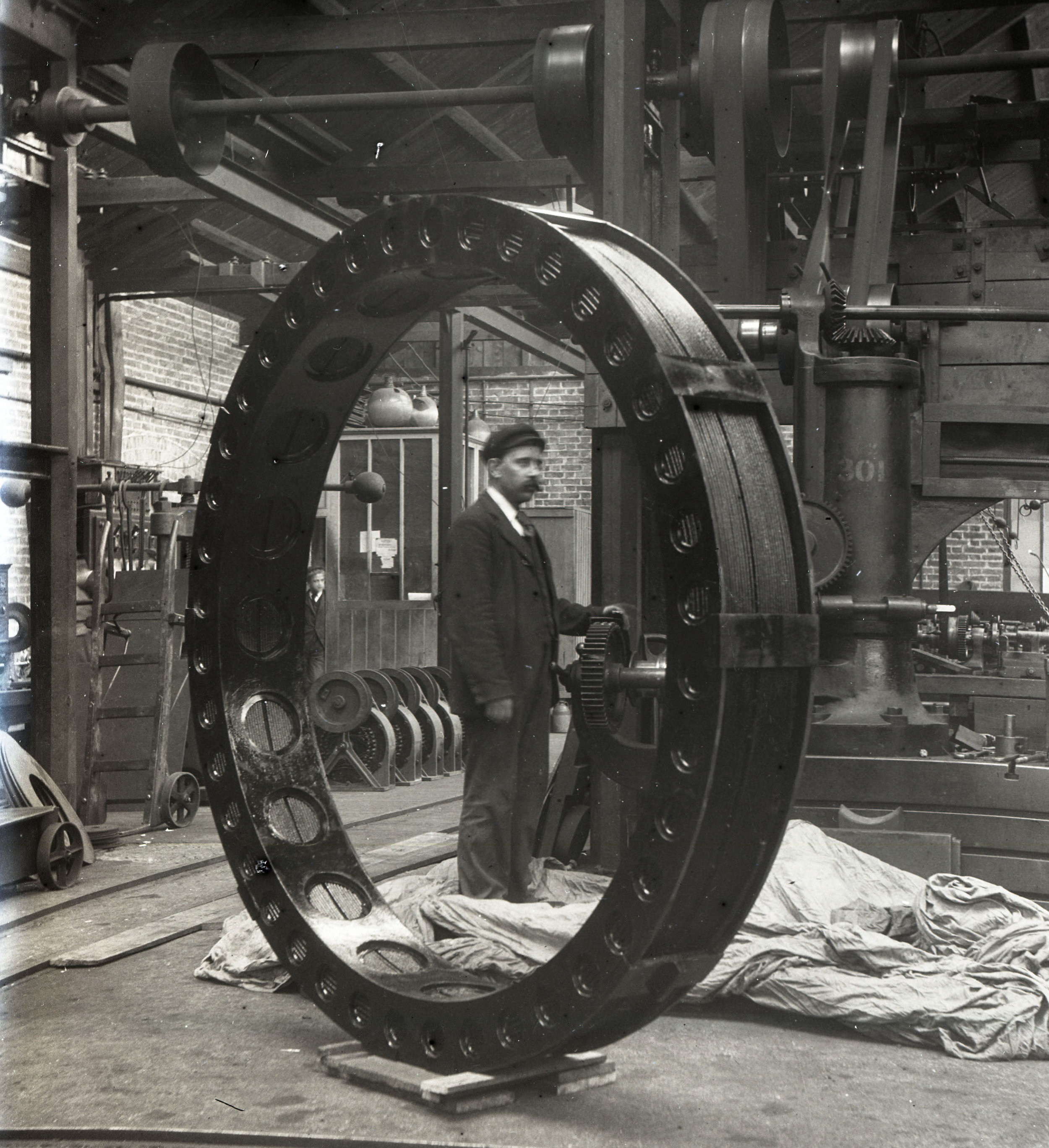

Life and Times

The world has changed a lot since 1900 - these photos illustrate just a few of the differences.

Places

Some gorgeous photos of some famous locations as they used to be.

Check out our Flickr account for more! Or, to view all the photos, head to our archival collections site and scroll down to Collection Tree.

Suggested reading:

For details of mountaineering and climbing in the first decades of the 20th century, check out the handbook Mountain Craft by Geoffrey Winthrop Young.

For more about some of the places depicted in these photos:

Mount Rainier a Climbing Guide by Mike Gauthier

Cascades Rock the 160 Best Multipitch Climbs of all Grades by Blake Herrington

The North Cascades by William Dietrich

Mont Blanc the Finest Routes: rock, snow, ice and mixed by Philippe Batoux

Mont Blanc: 5 routes to the summit by Franȯis Damilano

Swiss Rock Granite Bregaglia: a selected rock climbing guide by Chris Mellor

Canadian Rock select climbs of the west by Kevin McLane

Sport climbs in the Canadian Rockies by John Marin and Jon Jones

Mixed Climbs in the Canadian Rockies by Sean Isaac

For more information about the person who took these photos, you can read Gilmour’s obituary in the American Alpine Journal.

Beasts of Burden

The Secret History of the Ice Axe

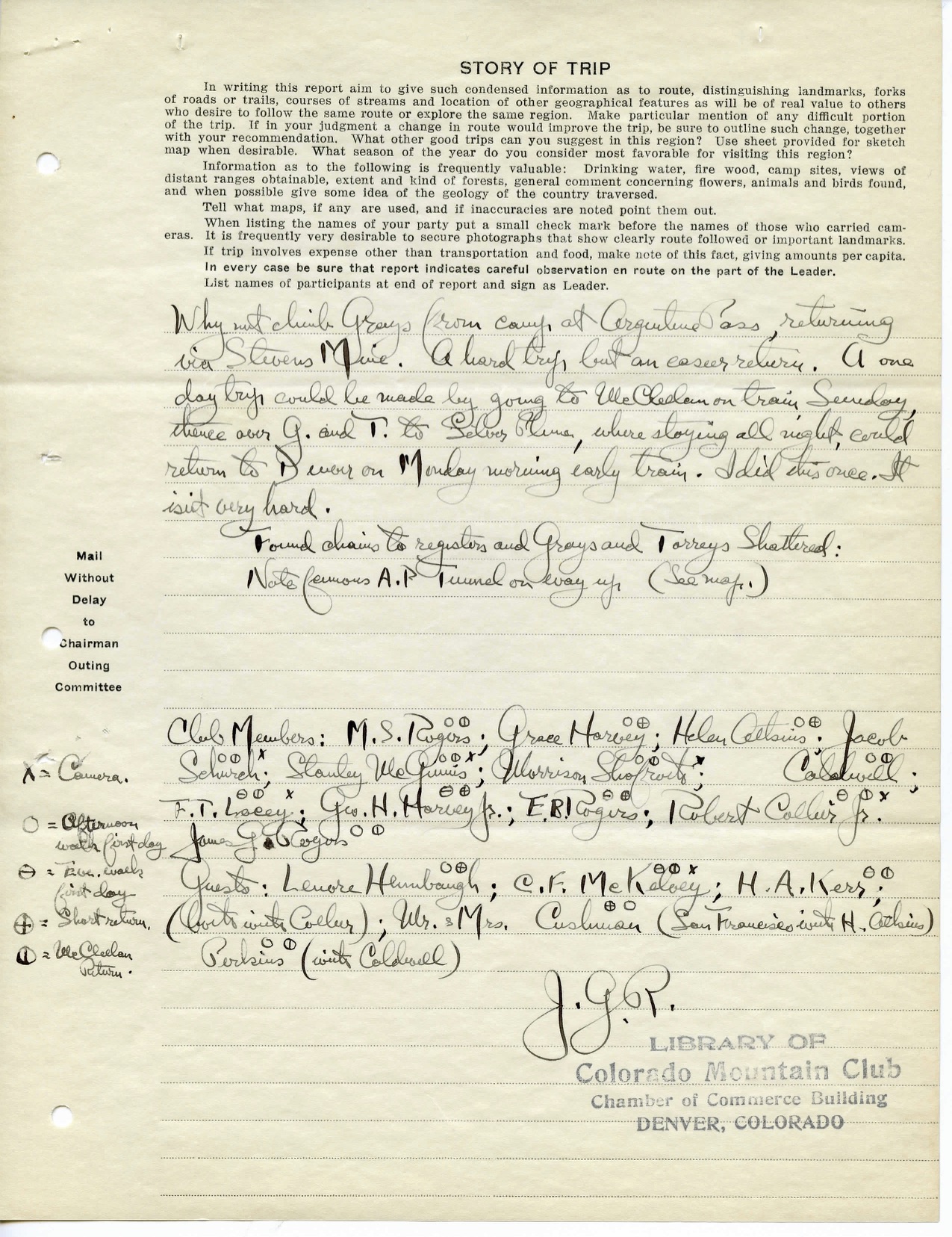

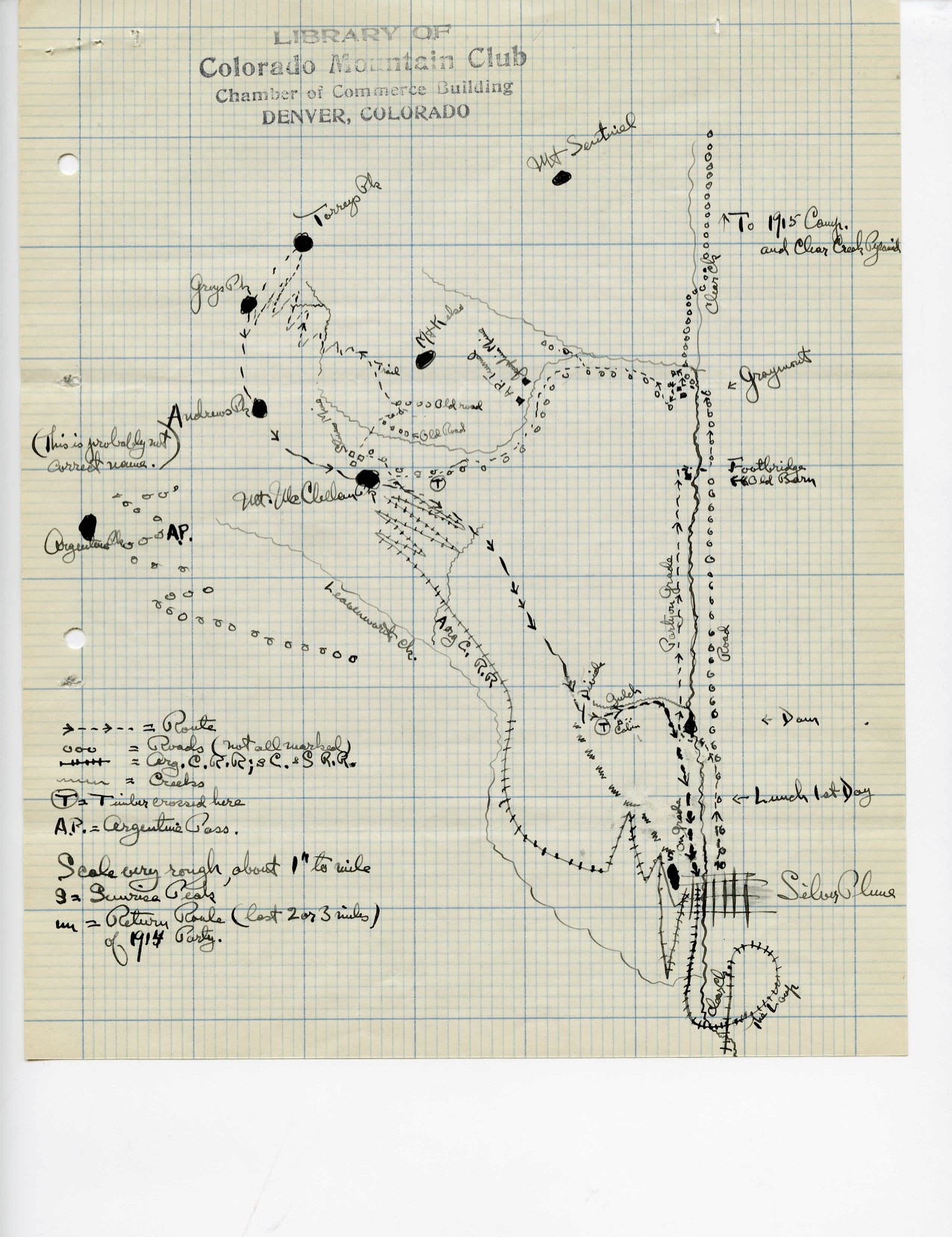

The Colorado Mountains: View from the Archives

Atop Mount Audubon, circa 1916-18.

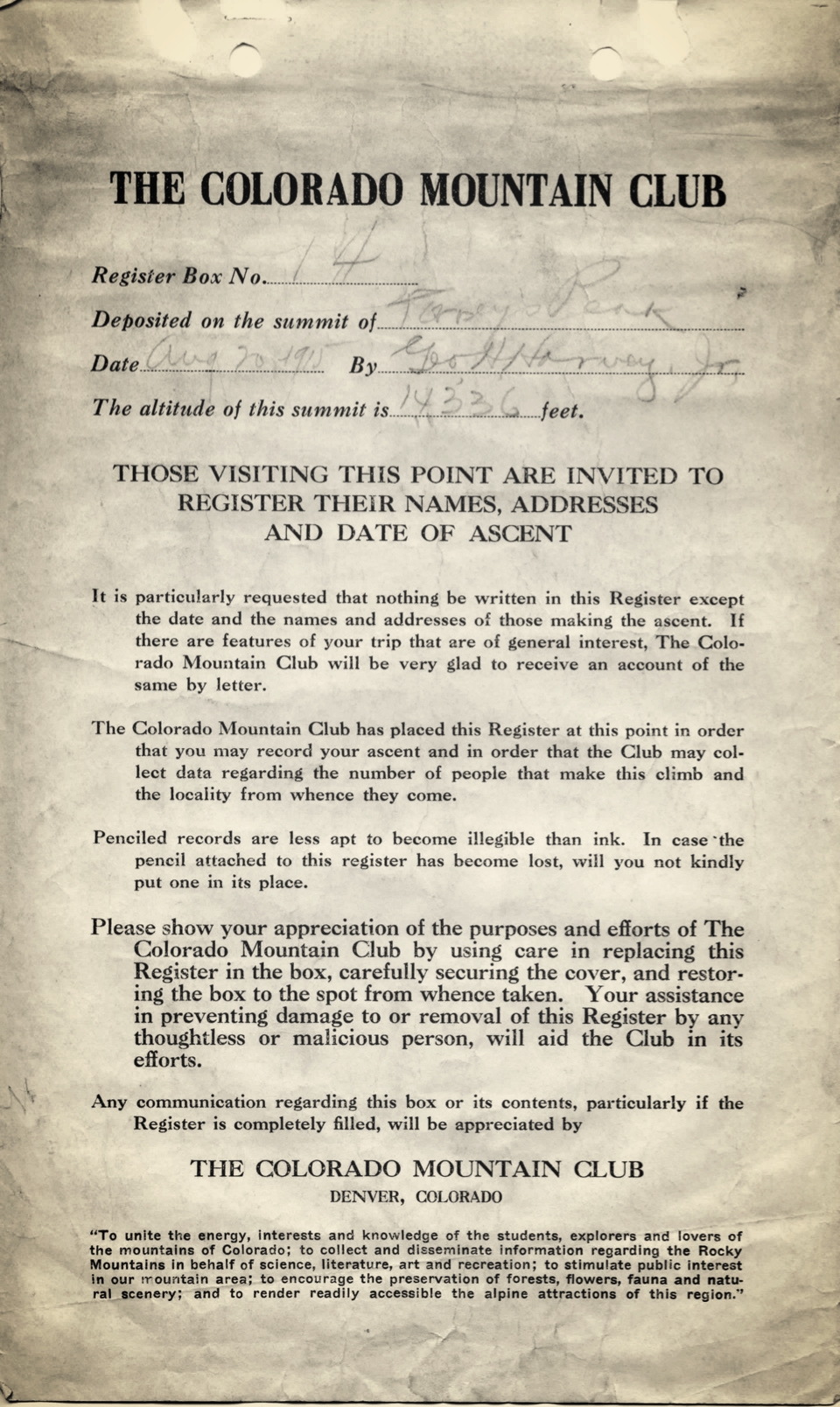

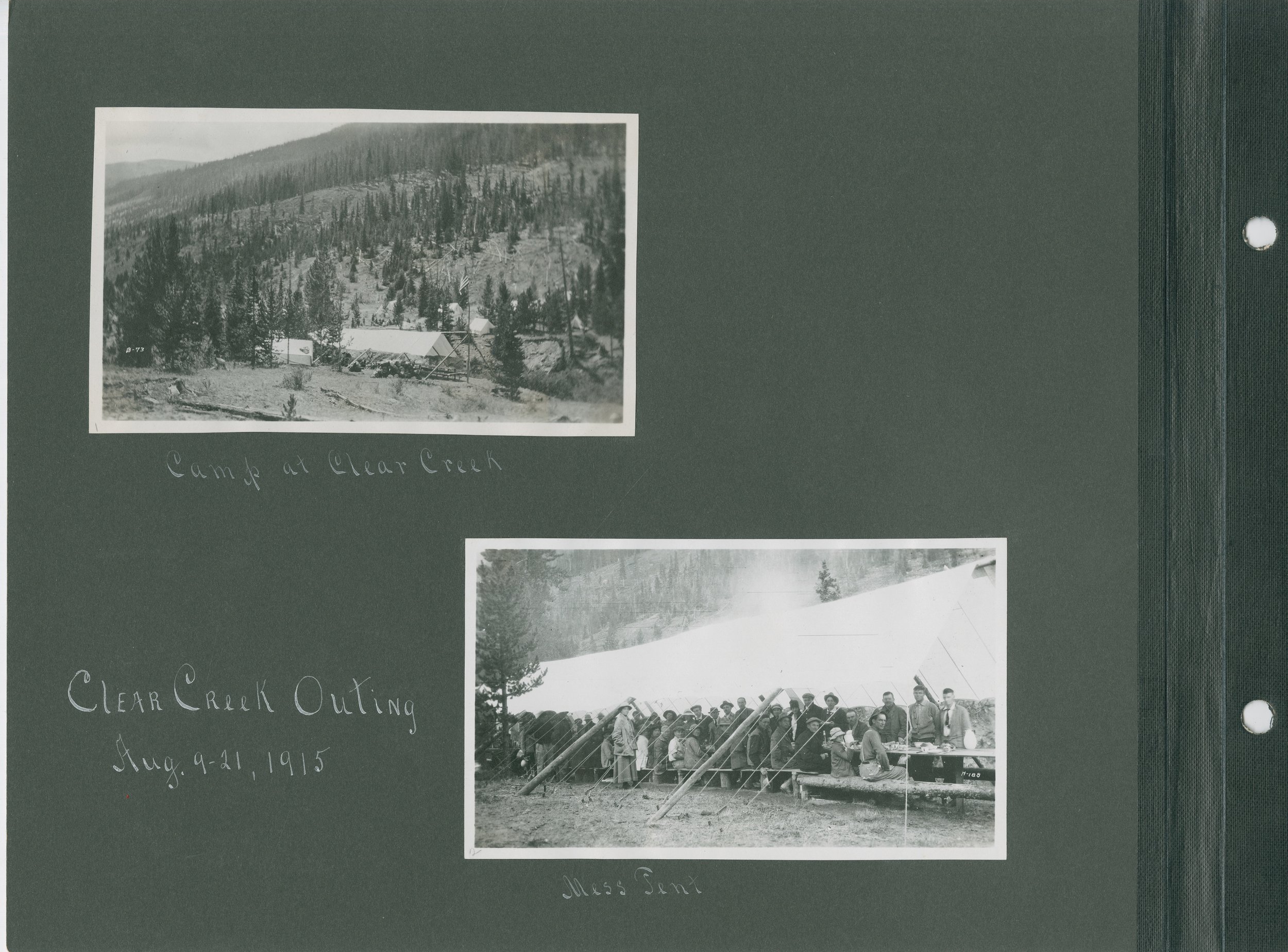

Now more accessible than ever! Thanks to a grant from the Colorado Historical Records Advisory Board, we were able to process and digitize a portion of the Colorado Mountain Club Archives.

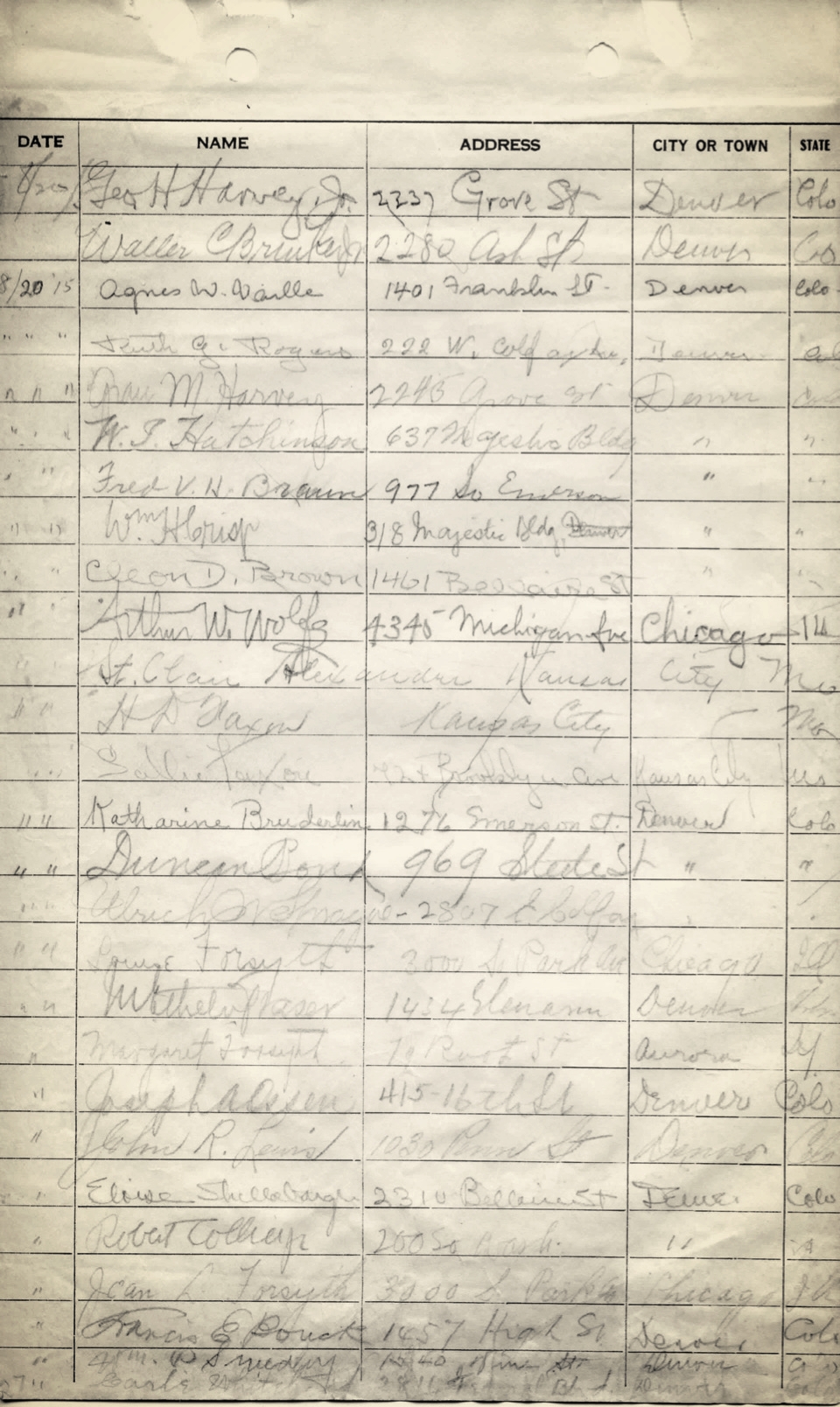

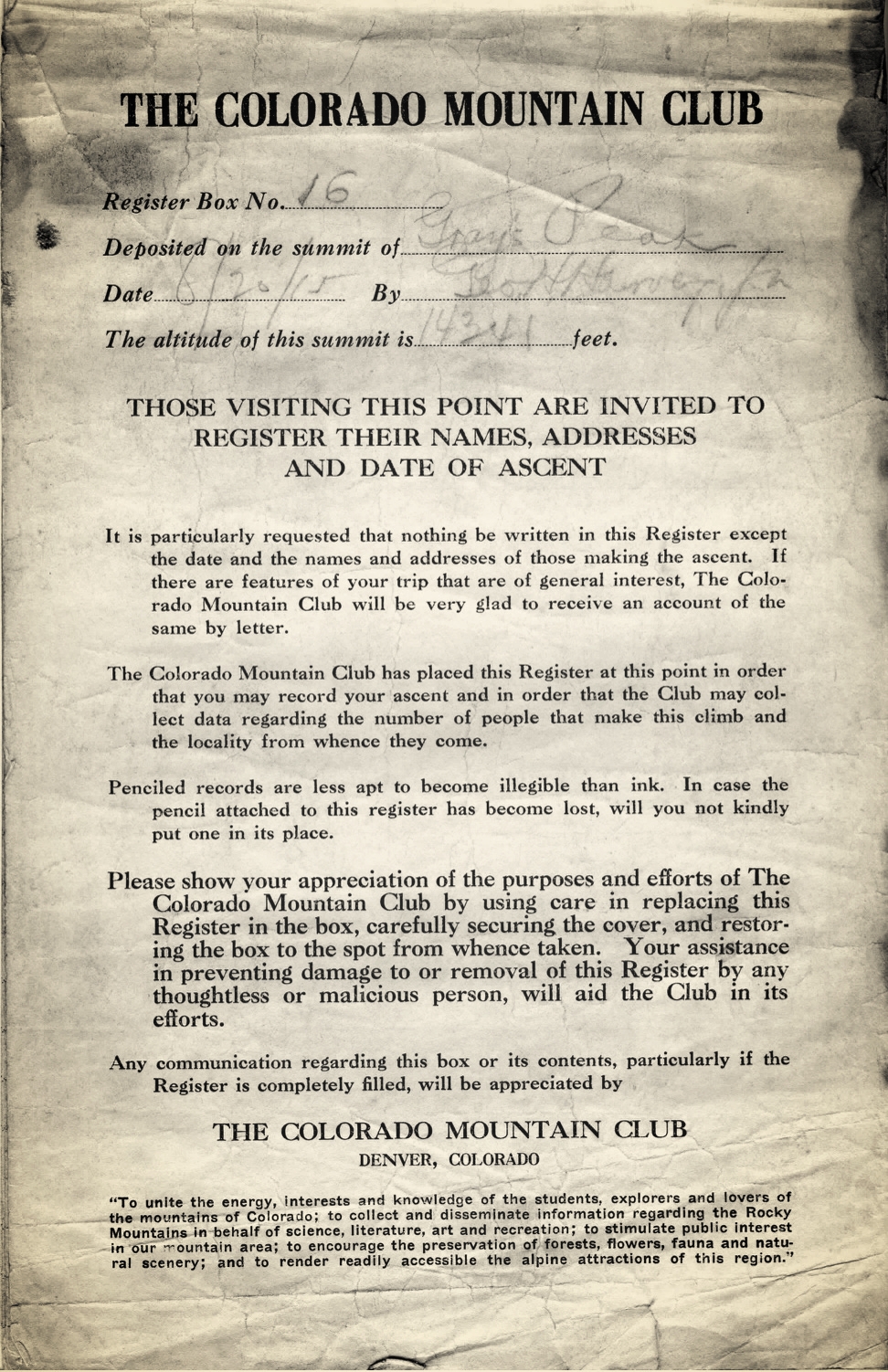

Located in the American Mountaineering Center, the Colorado Mountain Club (CMC) Archives are maintained by the staff of the American Alpine Club (AAC) Library. From April 2017 to May 2018, with a dedicated group of enthusiastic CMC & AAC volunteers, we organized, inventoried, rehoused, and digitized much of this collection. The most painful part was organizing the huge duplicate collection of Trail & Timberline back issues and flattening summit registers. Interested in purchasing back issues of the T&T? Contact us at library@americanalpineclub.org. Proceeds will go towards archives maintenance.

What's in the Colorado Mountain Club Archives?

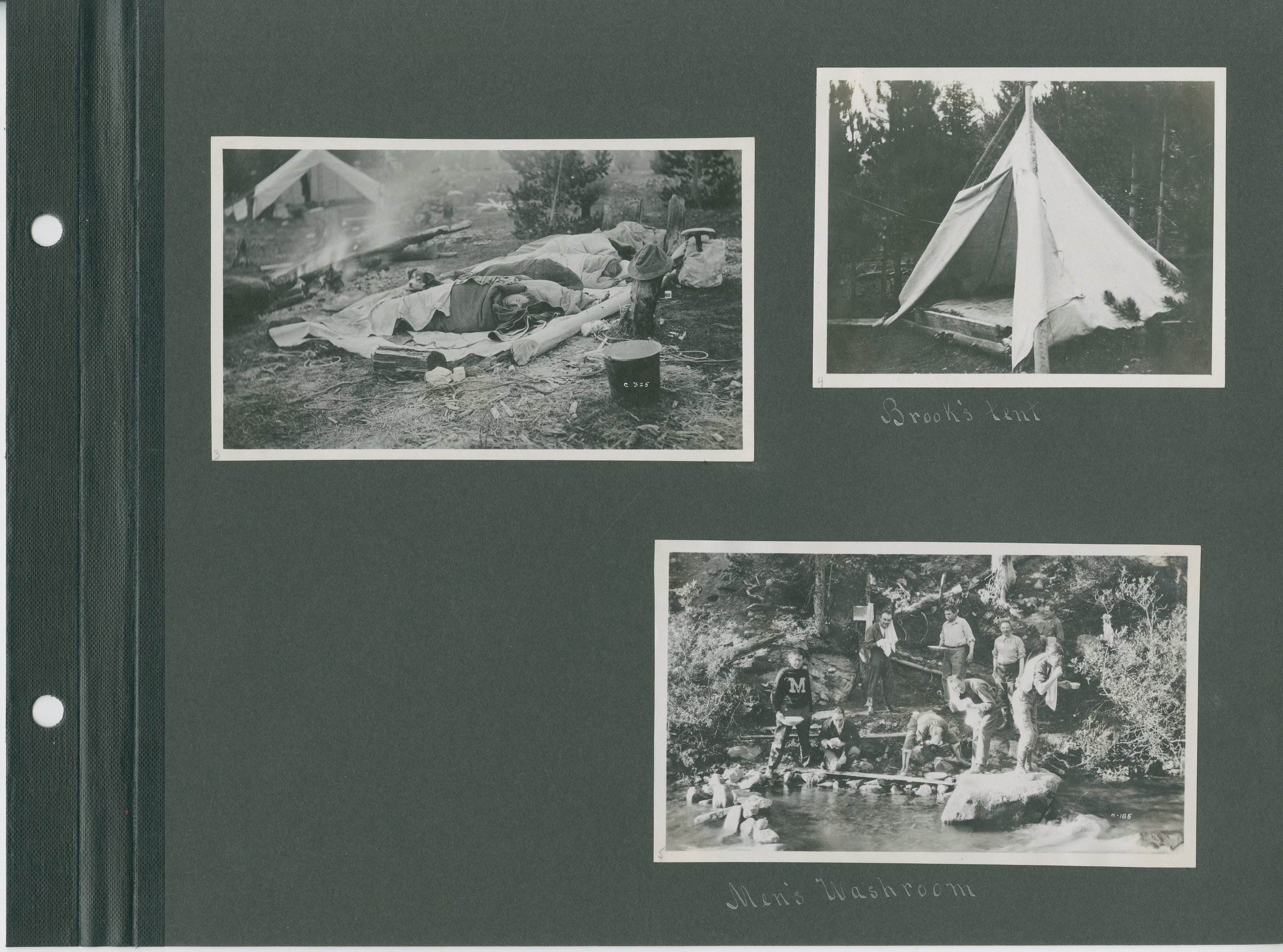

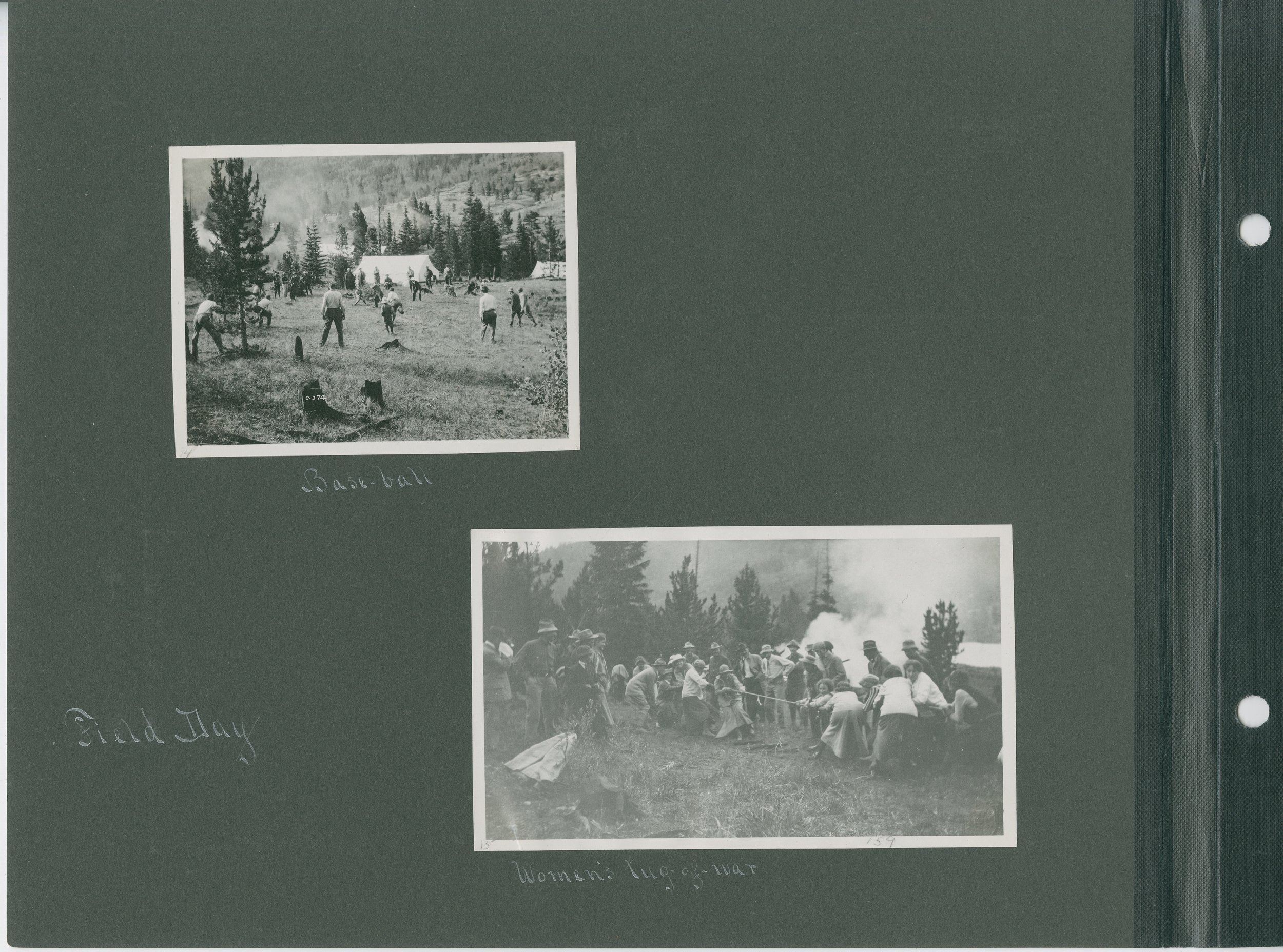

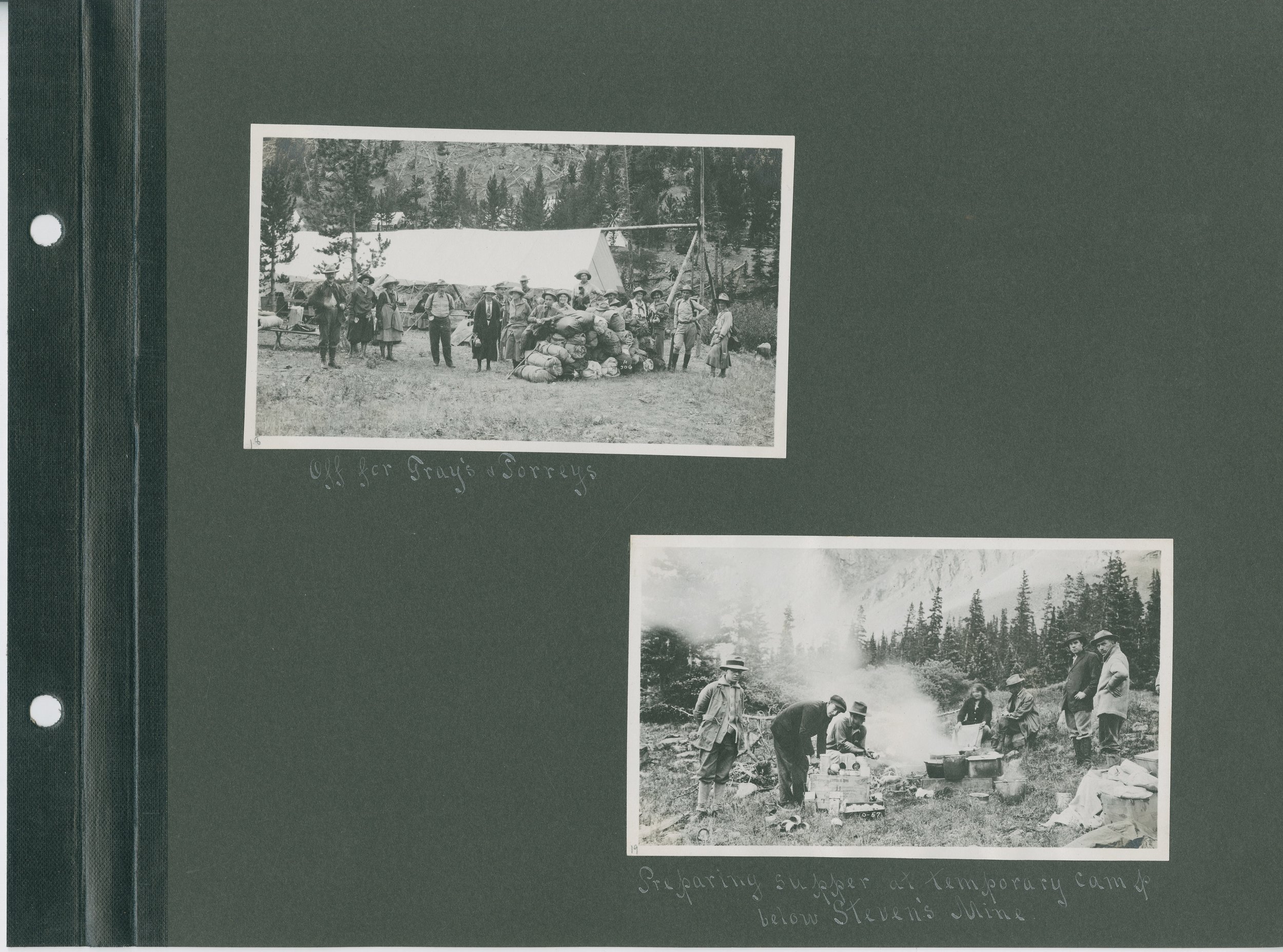

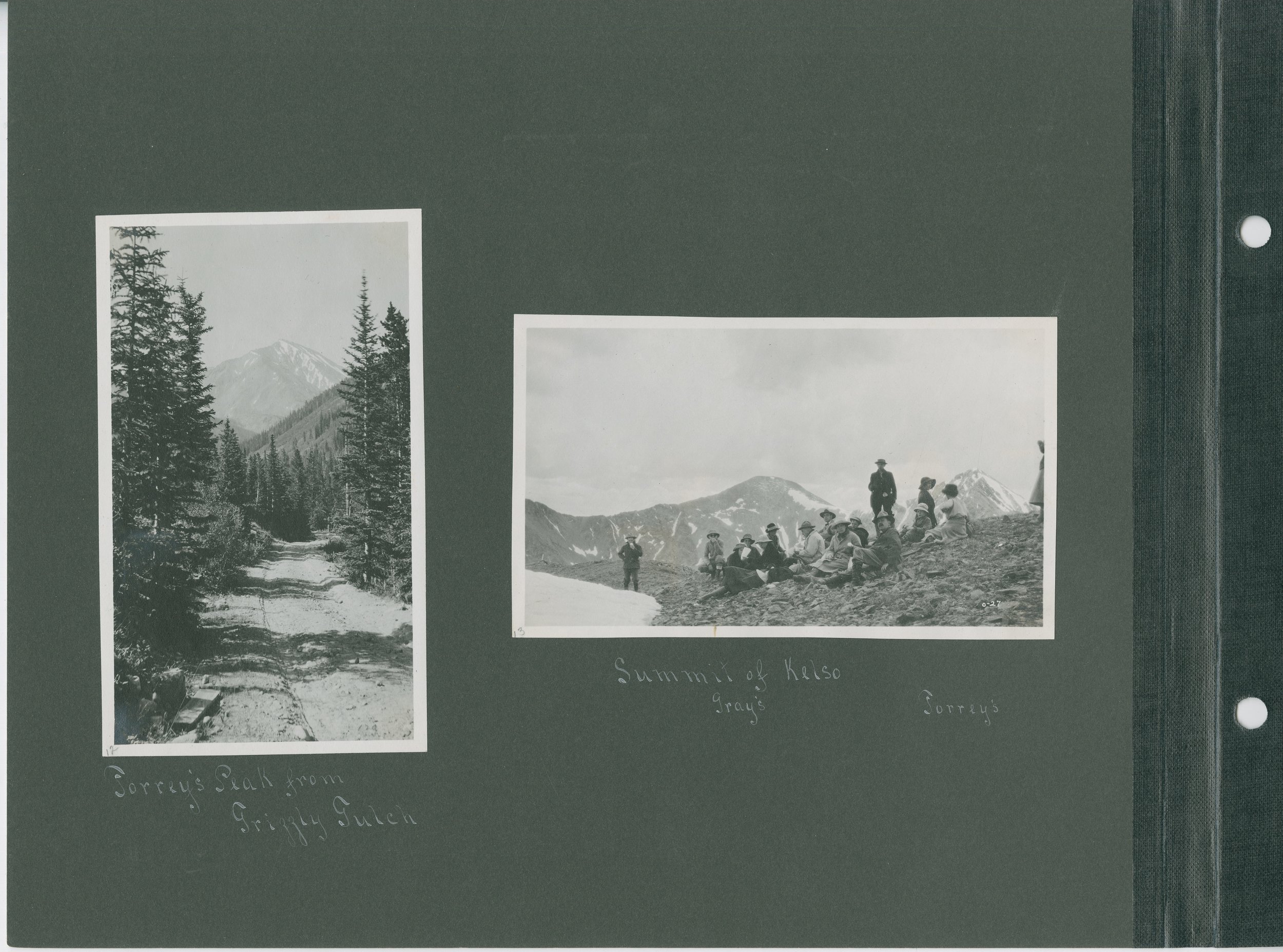

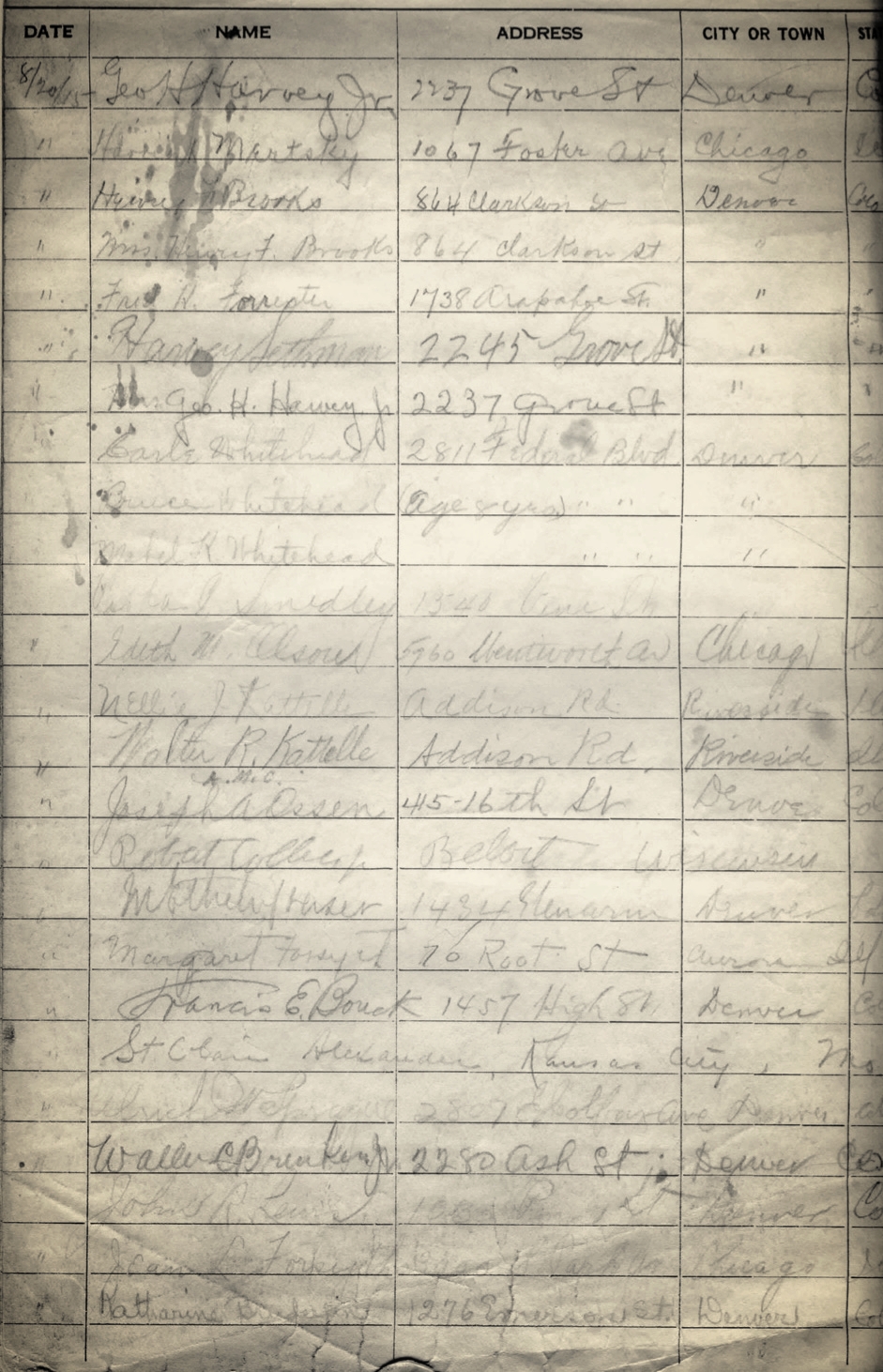

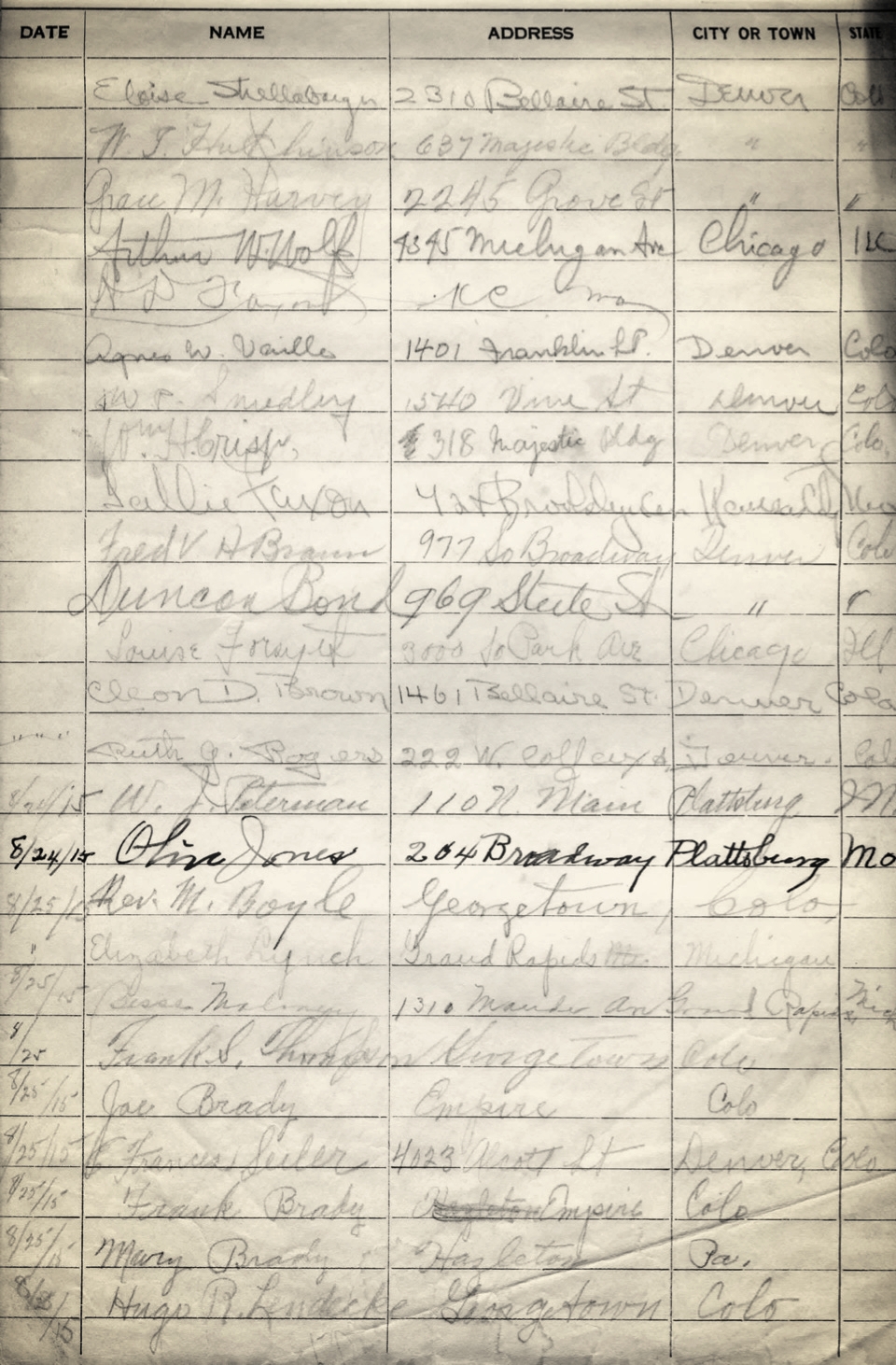

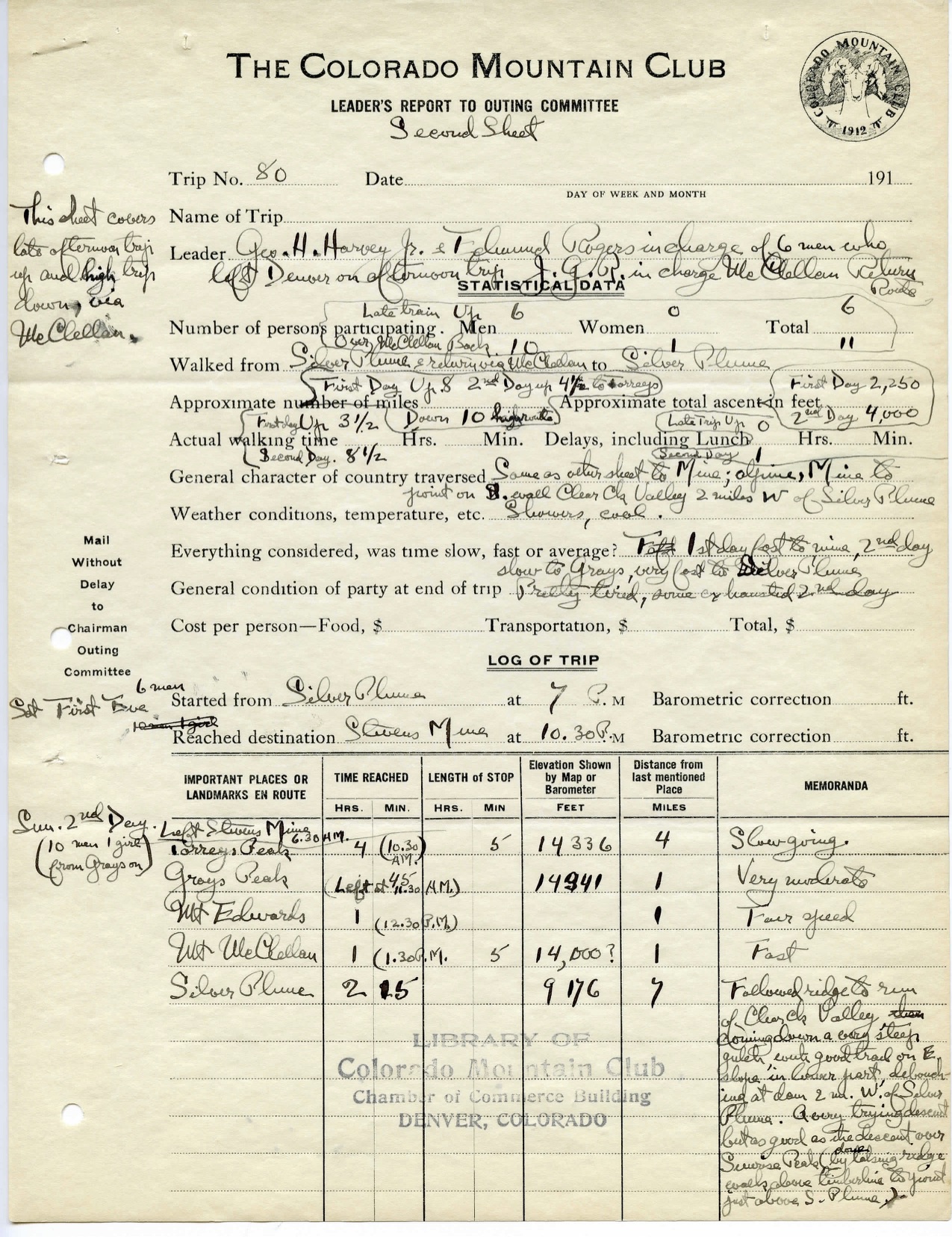

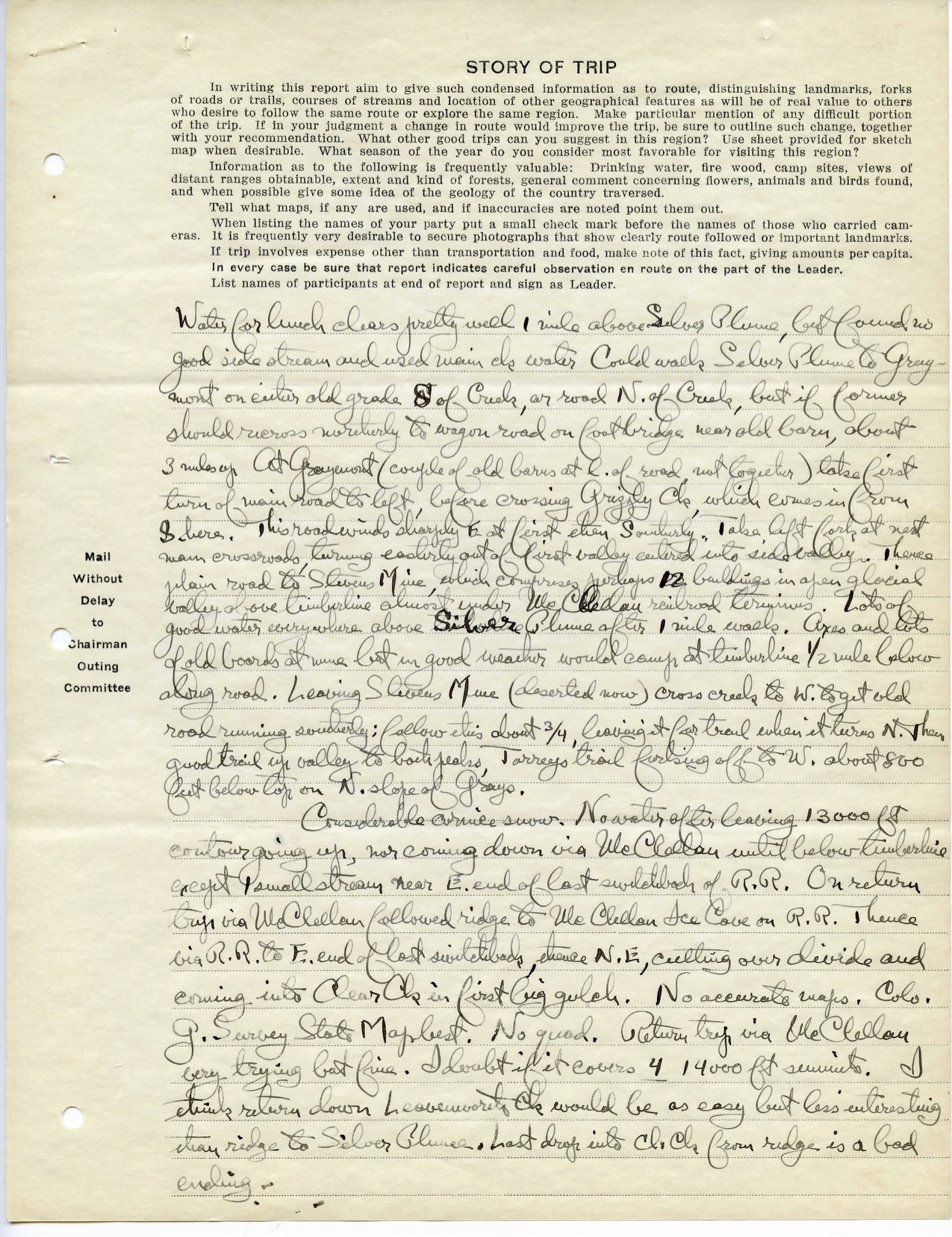

The archives date back to before the founding of the Colorado Mountain Club in 1912. There are trip reports, photographs, lantern slides, scrapbooks, old gear, 'Save the Wildflowers' posters, and much more. Currently, most of the early trip reports (over 1,150) have been digitized and eight photo scrapbooks. We are gradually adding them to our Digital Collections website. As we create and catalog finding aids, you can find them in our catalog here.

Putting It All Together

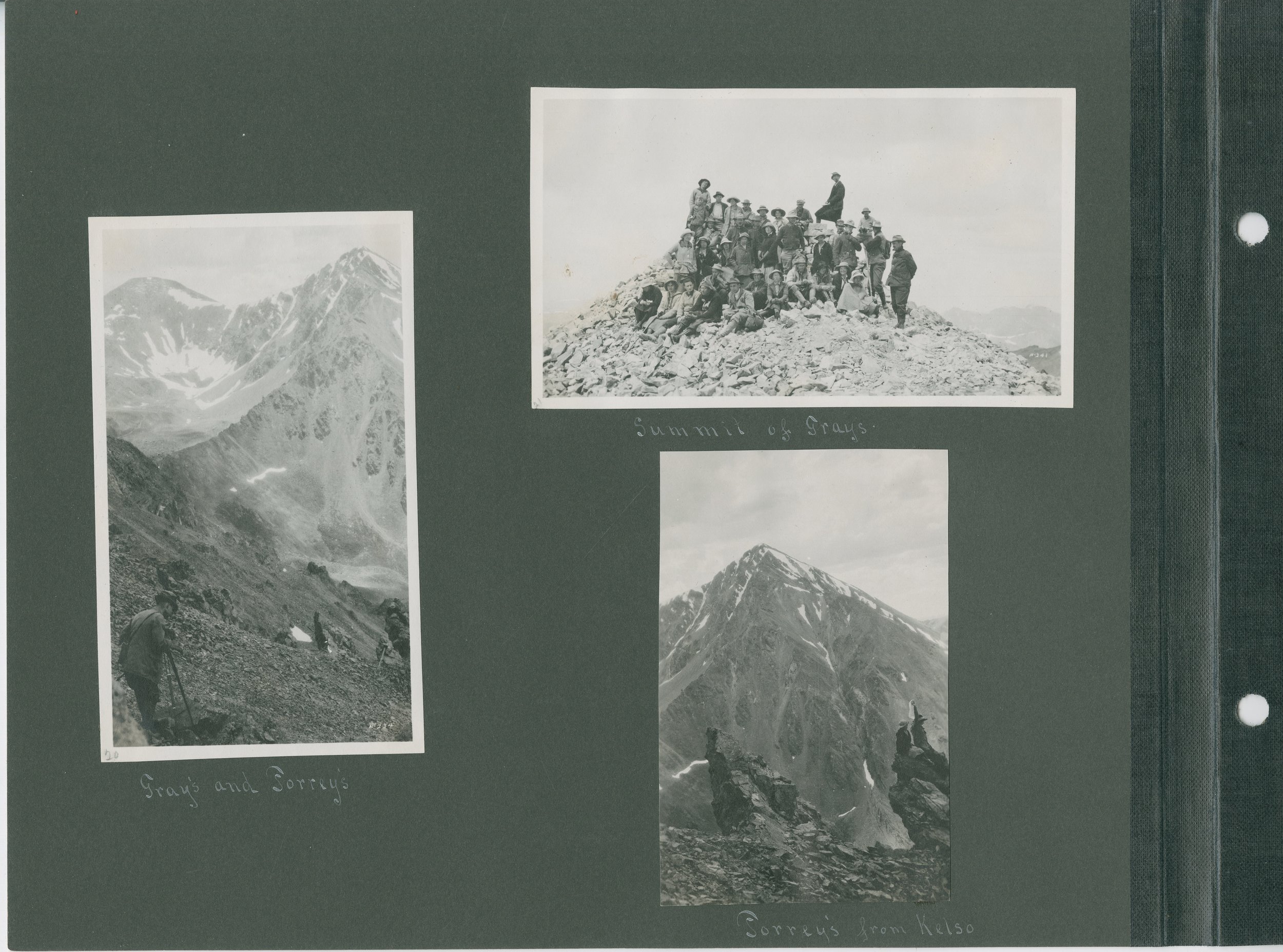

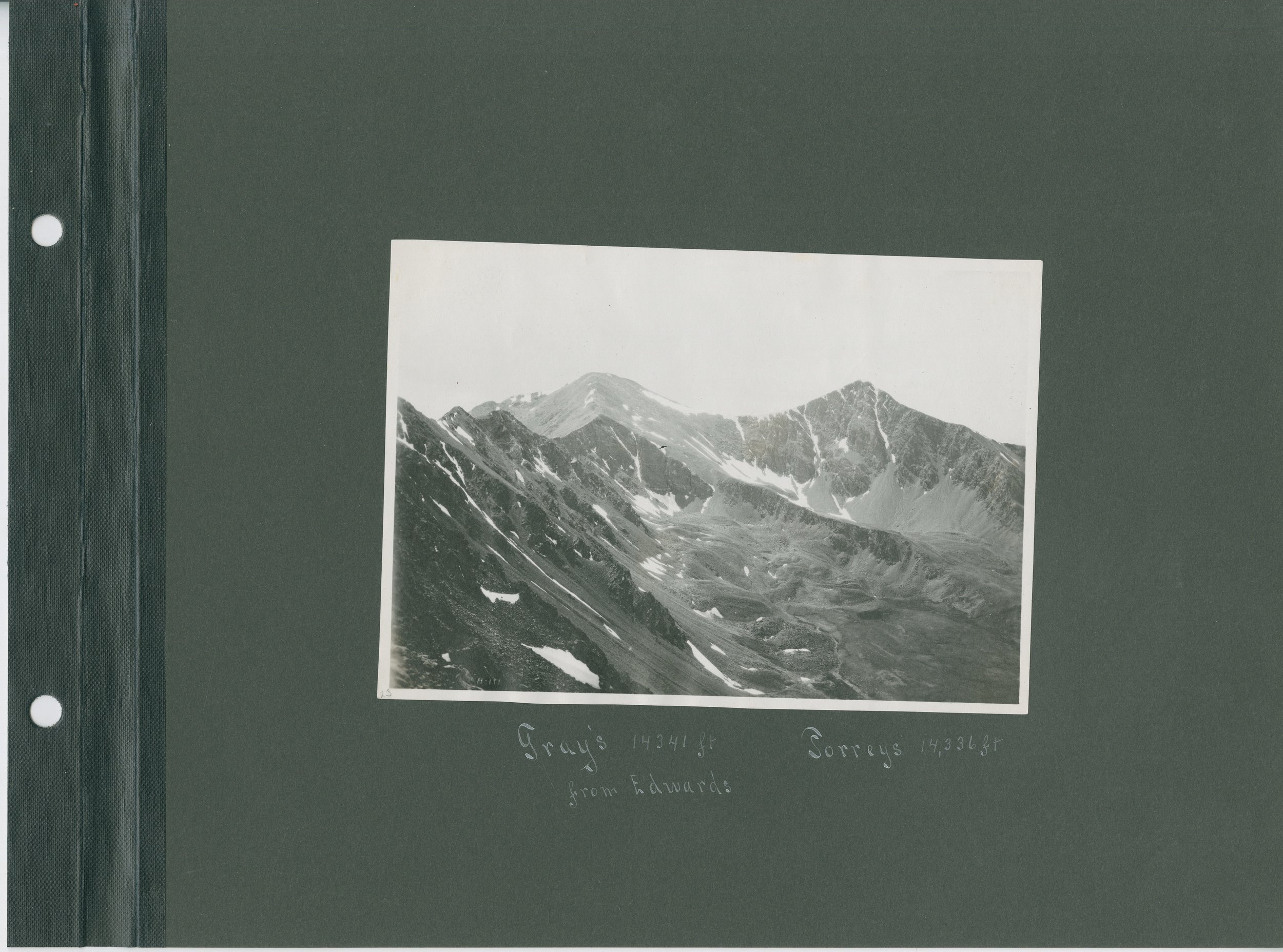

Having all of these records inventoried and cataloged makes it so much easier for researchers to find information. For example, you can now find photographs from the 1915 Clear Creek Outing on our Digital Collections website, with a selection seen below.

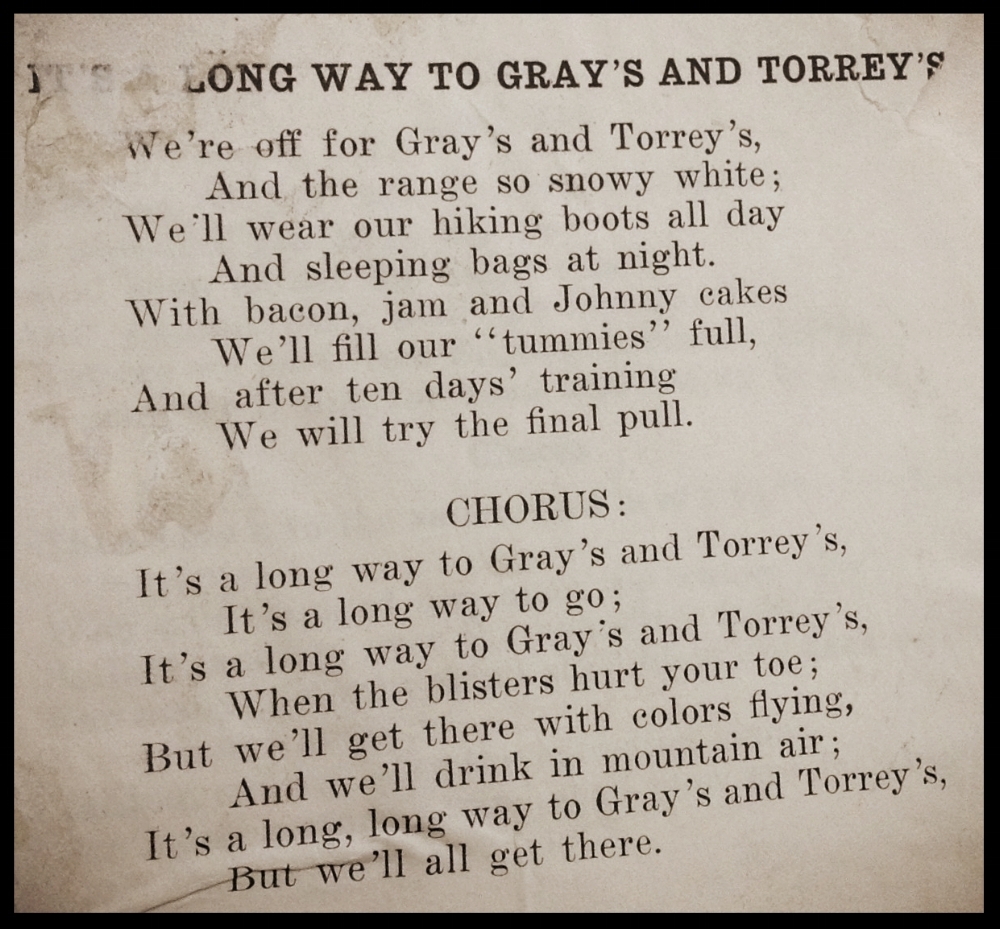

By searching the inventories, you can pair those photographs with the Song Book written by the Club members, the Grays and Torreys trip report and the summit registers that were signed by the CMCers when they climbed Grays and Torreys on August 20, 1915.

There are many more great records. Feel free to drop by the library and take a look. Keep an eye on our Digital Collections website as we are constantly adding more photographs and records.

This project was supported in part by an award from the Colorado Historical Records Advisory Board, through funding from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC), National Archives Records Administration. This project would not have been possible without the volunteers that inventoried, sorted, boxed, re-foldered, and scanned. Many thanks to Donna Anderson, Karyn Bocko, Dan Cohen, RoseMary Glista, Ann Hudgins, Peter Hunkar, Mike Lovette, Jan Martel, Barbara Munson, Roxy Rogers De Sole, Linda Rogers, Lin Wareham-Morris and Pat Yingst.

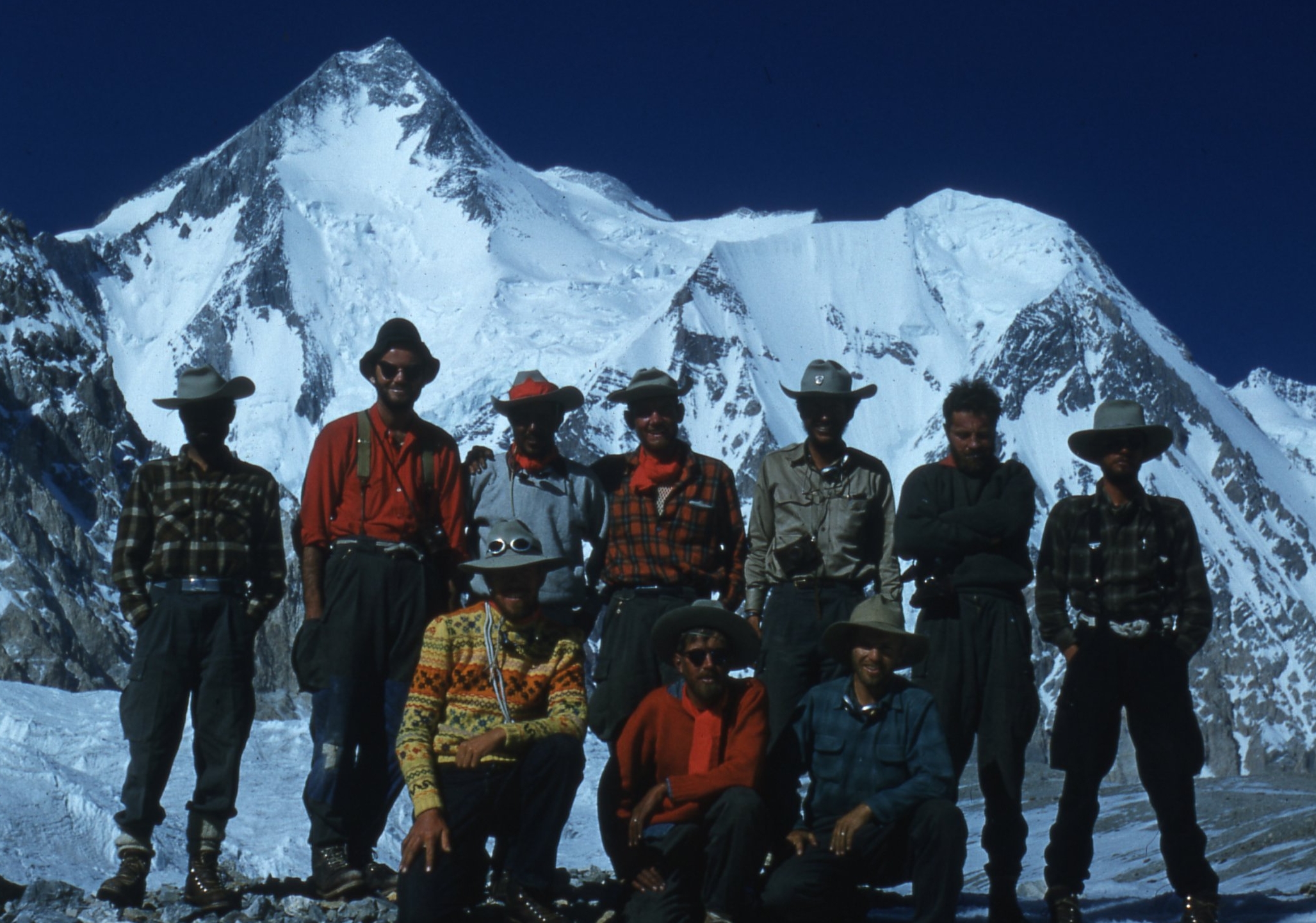

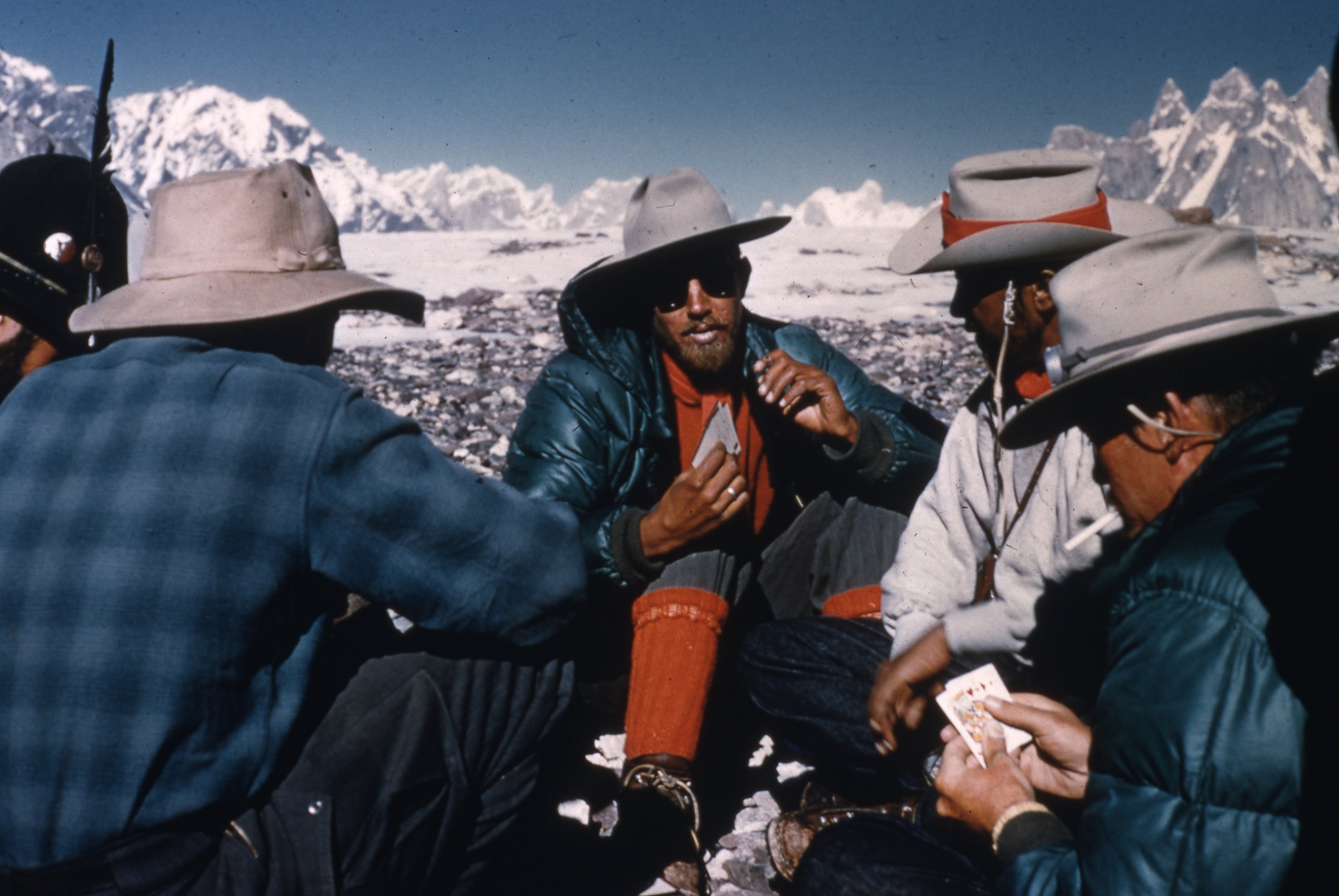

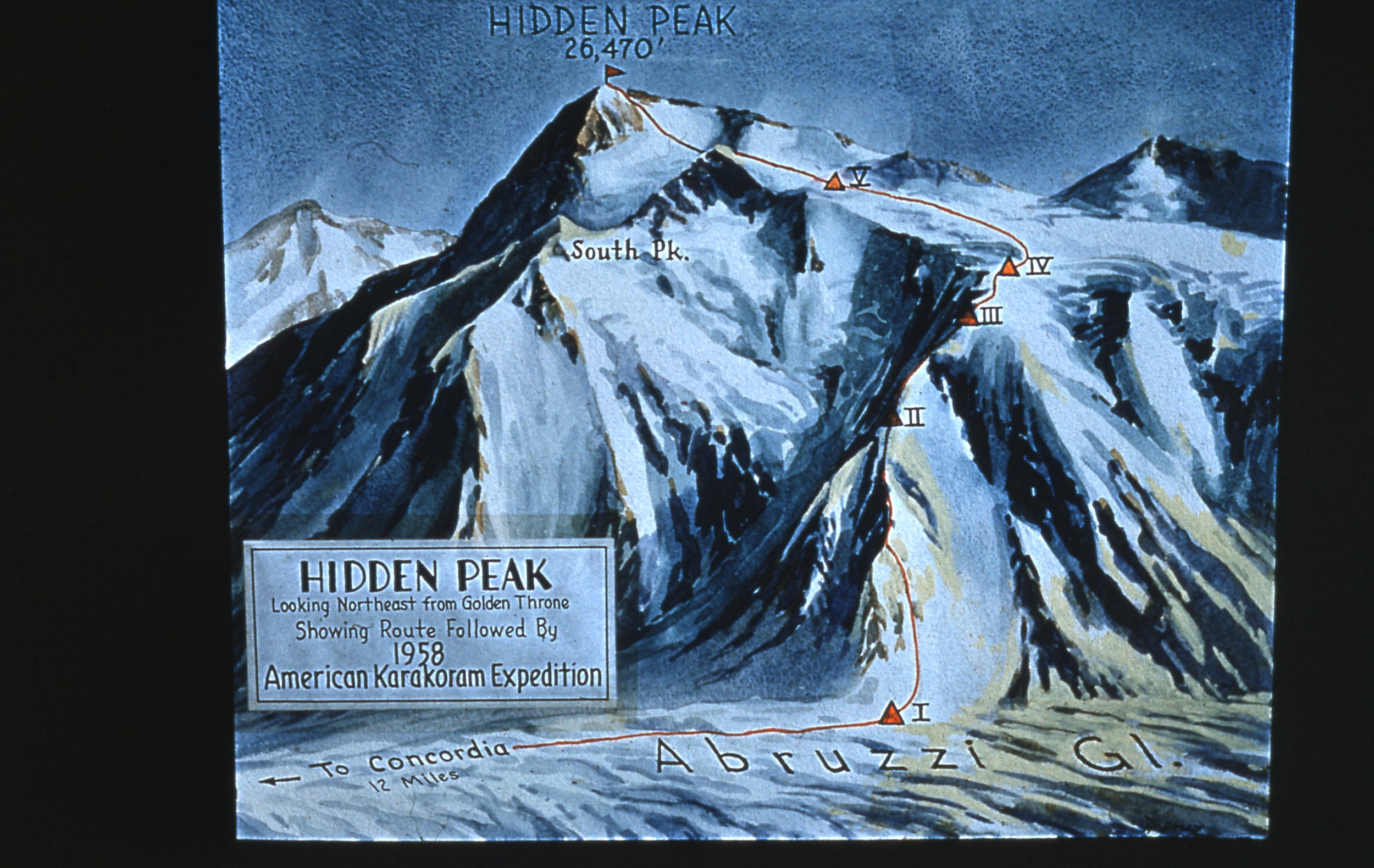

Happy Anniversary, Gasherbrum I First Ascent!

by Eric Rueth

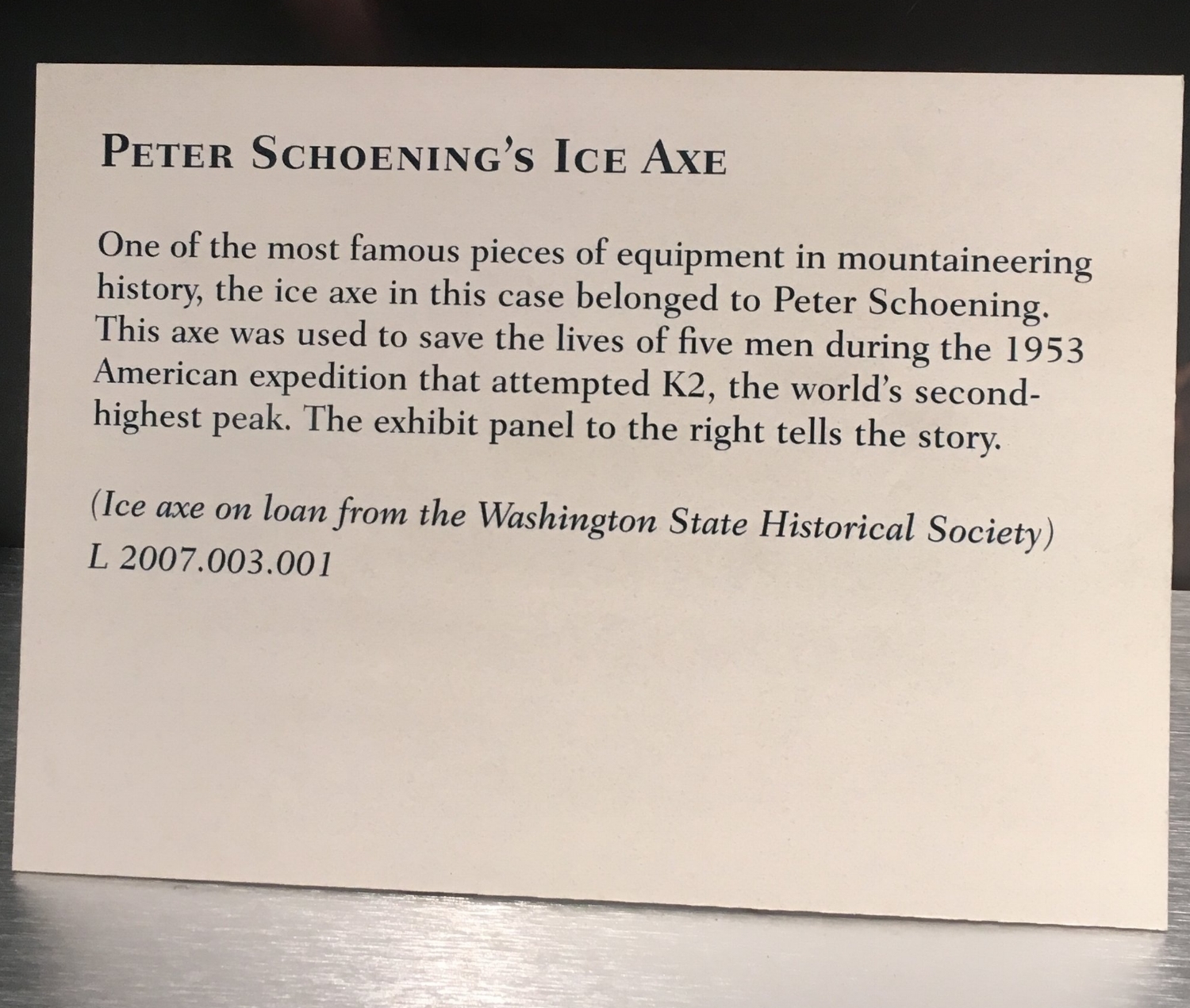

60 years ago today, Peter Schoening and Andy Kauffman topped a rounding ridge and had nowhere higher to go. After eight hours of climbing they found themselves on the summit of Gasherbrum I and became the only Americans to make a first ascent of an 8,000-meter peak.

"On July 4 all five os us started for Camp V which we hoped to establish at the 24,000-foot col between the south summit and the main peak" (Schoening, 1959).

To celebrate the ascent we're sharing some photo's from Andy Kauffman's collection.

To add some context here is the introduction to Pete Schoening's article from the 1959 American Alpine Club Journal and a link to the full article below.

"There is something exciting about expeditions. In part it must be the uncertainty of them. Perhaps this is adventure. But for Hidden Peak there was something even more. It could be the last chance for an American first ascent of an achttausender, and it seems extremely probable that first ascents of the fourteen achttausenders will become forever historically indicative of the mountaineering activity and ability of the various areas in the world.

Whether for adventure or history or whatever other reason, the ascent of Hidden Peak still required a party, permission and assistance from Pakistan, money, equipment, and an effort to carry out the attempt. Nick Clinch was the driving force behind the 1958 American Karakoram Expedition.* He was the "Director" and organizer.

Late in November 1957, Nick received Pakistani approval through the American Embassy in Karachi. From then on events began to occur at an increasing pace. Our freighter would leave New York by the end of March. In the middle of February as the party was being completed, I became a member. Besides Nick and myself, there were Andy Kauffman, Captain S. T. H. Risvi and Captain Mohd Akram of the Pakistan Army, Tom McCormack, Bob Swift, Dr. Tom Nevison, Gil Roberts, and Dick Irvin."

Click here to read the full "Ascent of Hidden Peak" article.

By Eric Rueth

For the Lady Mountaineer

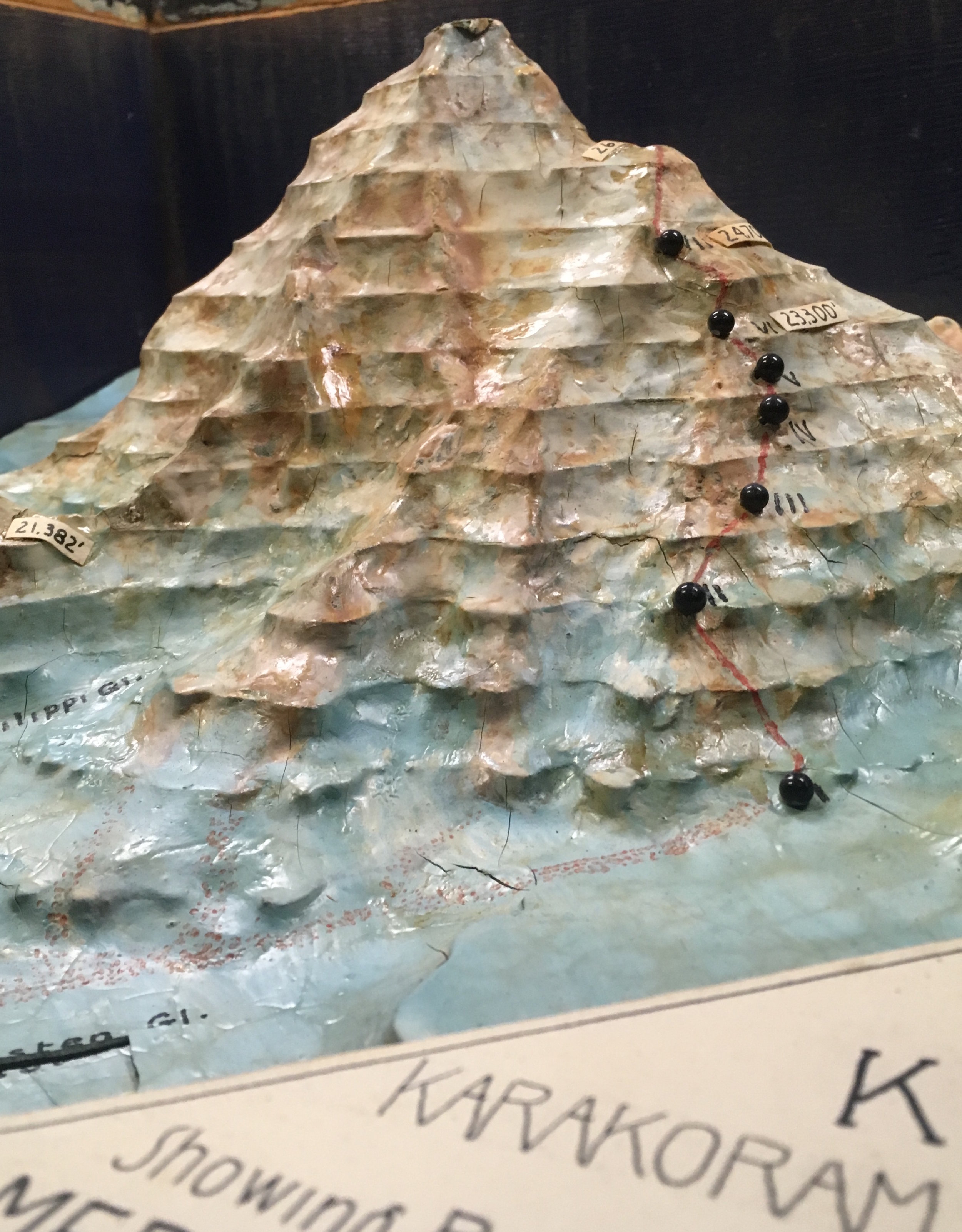

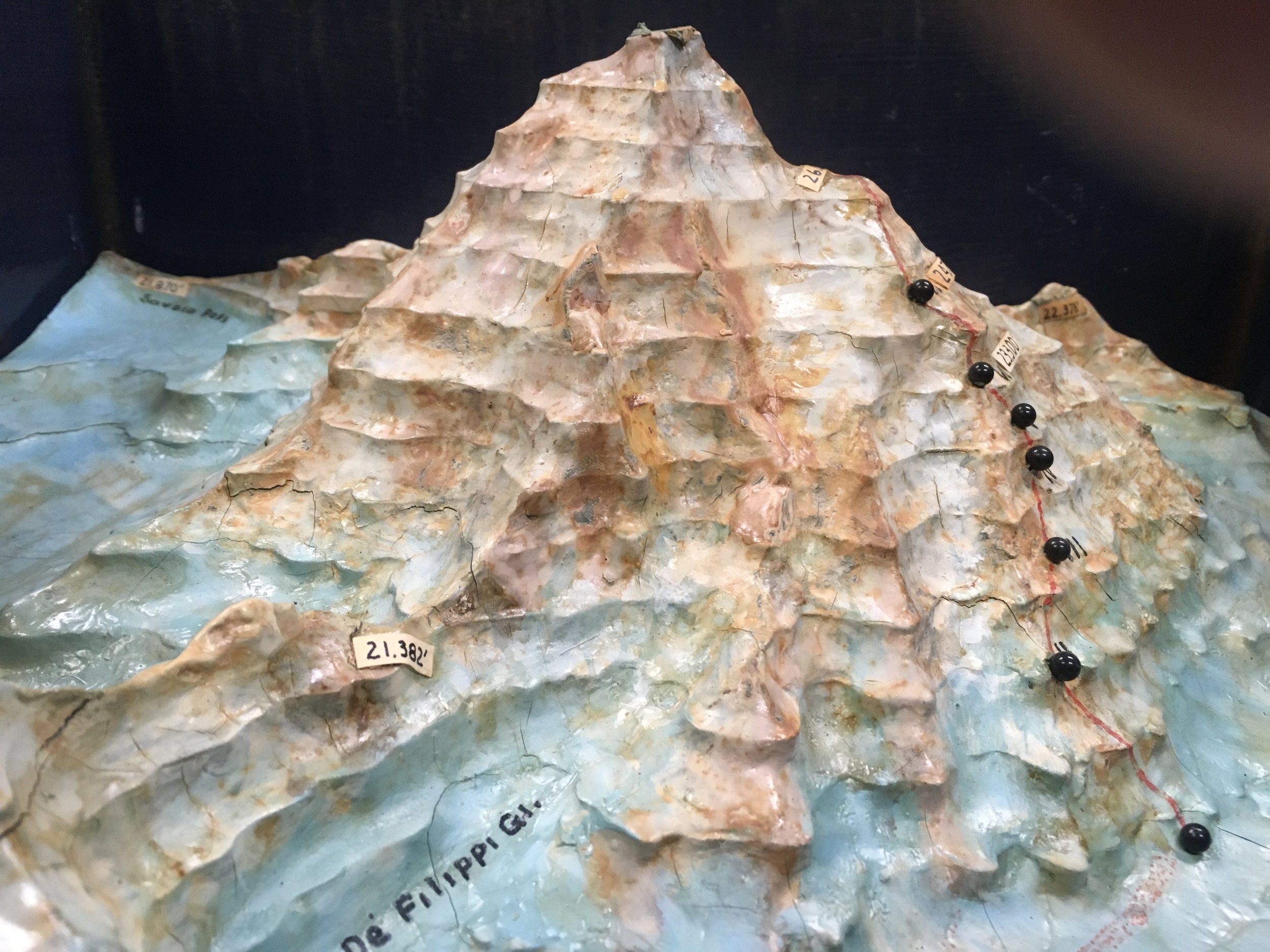

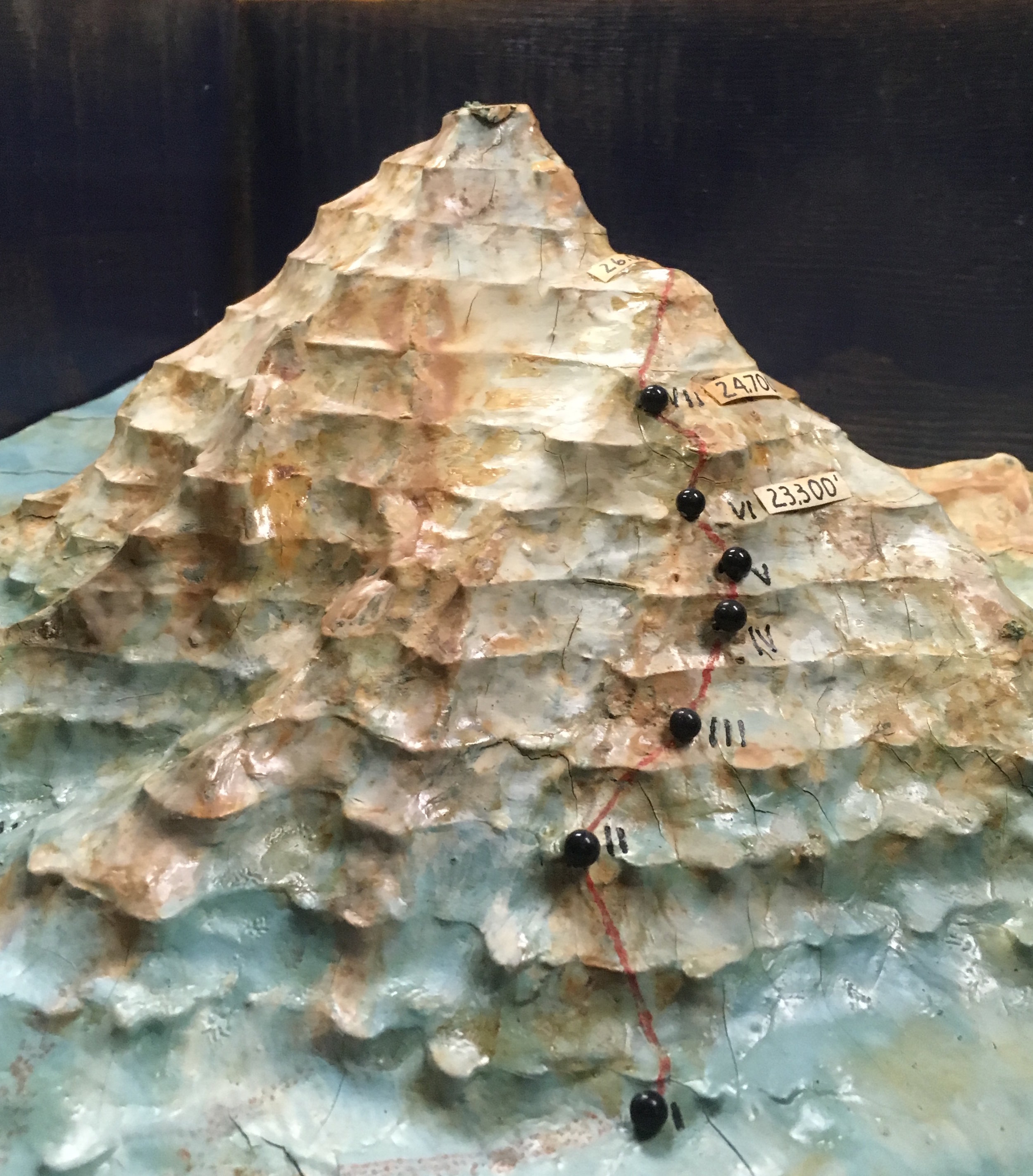

K2 1953: The Third American Karakoram Expedition

by Eric Rueth

Camp V (22,000 ft.) with Mashrabrum [sic] in the background. Photo, Third American Karakoram Expedition.

For the third and final installment of our pre-2018 Annual Benefit Dinner Americans on K2 wrap-up, we’ll take a look at the Third American Karakoram Expedition in 1953. It doesn’t seem possible to start this blog post better than the way Robert Bates started his article about the expedition in the 1954 American Alpine Club Journal,

“On 2 August 1953 all eight members of the climbing party of the Third American Karakoram Expedition, in excellent physical condition, were camped at 25,500 feet on K2 with ten days’ food. The summit of the second highest mountain in the world (28,250 ft.) rose less than 3000 feet above us. It was our hope to establish two men at Camp IX, at 27,000 feet or slightly higher, on August 3rd; and on the following day, if all went well, to thrust at the summit.”

The men high up on K2 were Dr. Charles Houston, Robert Bates, George Bell, Robert Craig, Arthur Gilkey, Dee Molenaar, Peter Schoening and Capt. H. R. A. Streather. After the 1938 First American Karakoram Expedition, Houston and Bates had been dreaming of returning to K2. Delayed by World War II and political conflicts between India and Pakistan they were finally able to return to K2 15 years later for a second attempt at the summit.

The optimism of reaching the summit by those eight men on August 2nd was met with a multi-day storm. At Camp VIII (25,500 ft.), the party was battered by heavy winds. One tent was completely ripped apart, forcing its occupants to seek refuge and residence in nearby tents. Even worse, the wind made keeping stoves alight impossible. Without being able to keep the stoves consistently lit, the party could not melt enough snow to stay hydrated.

After five days of being tent bound and becoming increasingly dehydrated, the storm began to lull. Now that it was possible to hear each other over the wind discussion of pushing higher up the mountain arose. But again optimism was met with disaster. When Gilkey emerged from his tent on April 7th, he immediately passed out.

Gilkey passed out from the pain that a charley horse had caused him. That charley horse turned out to be thrombophlebitis. Gilkey had blood clots in his leg. Getting Gilkey off of the mountain was now the main objective but hope still remained for an attempt on the summit. The party immediately broke camp to begin the descent, only to be turned back by the likelihood of an avalanche along the route. The storm raged on and the party bunkered down. On August 11th, the party’s hand was forced, Gilkey now had a clot in his other leg and more seriously in his lungs.

Capt. Streather at Camp III. Photo, Third American Karakoram Expedition

With the storm still raging, there was no other option than to descend. Any thoughts of a summit attempt were abandoned. Getting Gilkey down was now the only objective. Gilkey, who was unable to walk, was wrapped in his sleeping bag and the remnants of the destroyed tent; he would have to be lowered down the mountain.

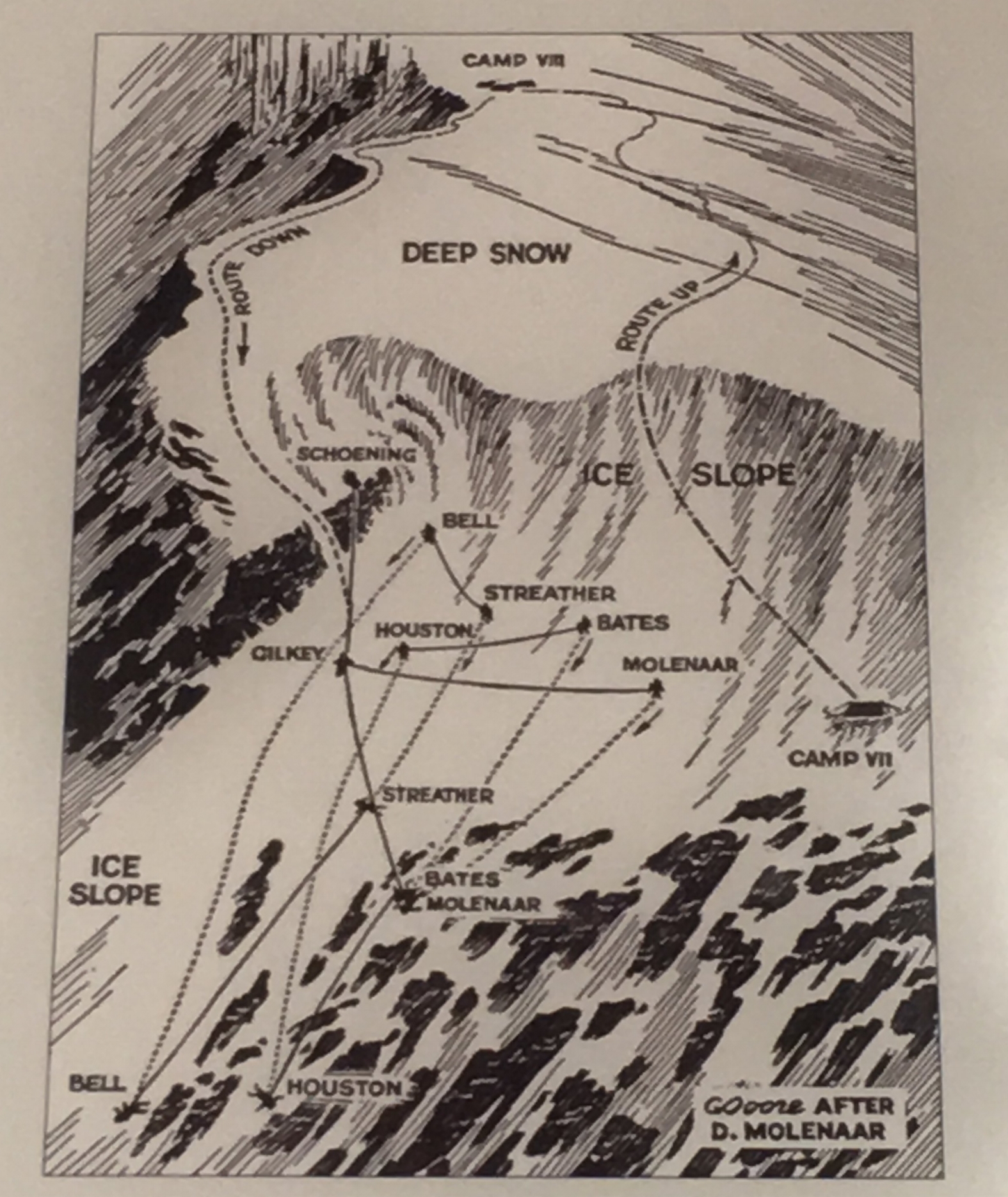

The going was slow and required every ounce of strength and focus from the party. The route used to climb up the mountain did not work for descending now that Gilkey had to be lowered. Schoening and Molenaar led the descent by finding a suitable route. The rest of the party would belay Gilkey and each other.

On the steepest pitch of lowering, the storm obscured the line of sight and made vocal communication with others below futile. First Schoening and Molenaar disappeared into the storm. Then Craig escorted Gilkey while he was being lowered until he too disappeared. Streather descended to a point where he could see Craig’s arm signals and relay commands to the rest of the party belaying. Already physically exhausted by the task of lowering Gilkey and being battered by the storm, those belaying were in for a test. Streather turned to the group and shouted, “Hold tight! They’re being carried down in an avalanche!” The group, the ropes, and the anchors held fast. Craig, who was not tied into any ropes, grabbed the ropes lowering Gilkey and held on for the duration.

Following the avalanche, the party was absolutely exhausted. The party was close to the small ledge that served as Camp VII. Craig traversed to the Camp VII to gather himself after surviving the avalanche and to attempt to enlarge the ledge so the entire party could recuperate from the physically and mentally demanding day.

With Craig at Camp VII, the rest of party continued the extremely slow process of working their way towards the ledge. Bell was working his way over a difficult stretch of an ice gully when another catastrophic event occurred, Bell lost his purchase and started falling down the mountain. The hard ice prevented a self-arrest by Bell and Streather, who was tied into the other end of Bell's rope. The location of the pair when they fell set off a chain reaction that would send the entire expedition, except for Craig alone at Camp VII, down the mountain to the Godwin-Austin Glacier two miles below.

Only the entire expedition didn’t disappear over the edge of the mountain and fall two miles through the void. As members one by one were caught up in ropes and pulled from their feet, they tumbled and somersaulted downwards picking up momentum along the way until all of a sudden the rope grew taught. Schoening arrested the fall of his six companions in a moment that will forever be known as, “the belay.”

The entanglement that caused the catastrophic fall down the mountain also worked to save the expedition. Various injuries and lost gear resulted but the expedition suffered no loss of members.

This diagram by Clarence Doore follows an illustration by Dee Molenaar. It is one display at the American Mountaineering Museum.

Eventually making it to Camp VII the ledge still needed to be bigger before tents could be set up and the party could put the horrific day behind them. Gilkey was secured with two ice axes beneath a rock rib while the space was expanded. When camp construction was completed Streather, Craig and Bates went to retrieve him. Only, upon their arrival at the rock rib they found a bare slope. Gilkey and his anchors were gone, swept away by an avalanche.

The night that followed the horrific day would offer little rest. The party had been pushed to the limit physically, mentally, and emotionally and were now cramped together in two tents on a precarious ledge. The storm still raged on and Houston, who had suffered a concussion, would wake up in a state of confusion consequently waking up everyone else.

The next day the storm continued and so did the party. It took four days for the battered party to descend from Camp VII to Camp II. At Camp II, the party was met by porters who provided food and comfort after their heroic and tragic descent.

As they departed the mountain, the expedition built a large cairn memorial for Gilkey near the confluence of the Savoia and Godwin-Austen Glaciers. The memorial still stands to this day and has grown to be more than a memorial only to Art Gilkey; the Gilkey Memorial is now used to remember all who have perished on the Savage Mountain.

With the conclusion of the 1953, there had been three attempts made by Americans on K2. The first had been successful as a reconnaissance but failed to reach the summit. The following two ended without the summit being reached and tragic loss of life. Americans had paid a high price for their efforts on the mountain and it wouldn’t be until 1978 that the mountain would finally yield to Americans.

Read about the Second American Karakoram Expedition here.

Read about the First American Karakoram Expedition here.

*These blog posts were an attempt to sum up the American attempts on K2 prior to the successful expedition in 1978. Unfortunately they leave out a lot of the nitty gritty details and personalities of those involved. If your interests have been piqued you can read the full expedition reports in the American Alpine Club Journal at publications.americanalpineclub.org or if you're an AAC member you can checkout some of the many books about K2 in the AAC Library at booksearch.americanalpineclub.org.

By Eric Rueth

K2 1939: The Second American Karakoram Expedition

by Eric Rueth

K2. Jack Durrance Collection.

After the successful reconnaissance of K2 in 1938, the Second American Karakoram Expedition was poised to make history. A route on the Abruzzi Ridge had been established up to 26,000 ft. with locations for campsites and beta on the difficult sections of climbing. If weather permitted, there seemed to be no good reason why history would not remember the Second American Karakoram Expedition as the first to summit K2 and the first to conquer an 8,000m peak. But the events would play out differently on the mountain and history now remembers the 1939 expedition for its tragedy and the controversy that followed.

The party that arrived at the base of K2 in 1939 was not a strong one. It was originally planned to include 10 members but after dropouts for various reasons it dwindled to five. The biggest issue with the loss of these members was that they were the five most qualified members (excluding Wiessner) and left the expedition with no returning members of the 1938 expedition. A last minute addition brought the party up to six and included: Fritz Wiessner, Eaton Cromwell, George Sheldon, Chappel Cranmer, Dudley Wolfe, Jack Durrance (the last minute addition). They were also accompanied by a British Transport Officer, Lt. George Trench and 8 Sherpa who climbed up the mountain: Lama, Kikuli, Dawa, Tendrup, Kitar, Tsering, Phinsoo, and Sonam.

1939 Expedition members. Left to right, standing: George Sheldon, Chappell Cranmer, Jack Durrance, George Trench; seated: Eaton Cromwell, Fritz Wiessner, Dudley Wolfe. Jack Durrance Collection

The weakness of the team was not that any of the members were on the team; it was that these members were the team. Each team member had their strengths but unfortunately also their limitations. As climbers kept dropping out of the expedition, it lost its well-rounded and experienced members that could have potentially brought the best out of the team. Fritz Wiessner was the only fully qualified and experienced climber to arrive at K2. To add to the weakness of the team, a number of events weakened it further.

First was that due to the timing of Durrance’s addition, his boots were set to arrive at some point after the party’s arrival at K2. The boots finally arrived four weeks after the party was making their way up the mountain. Durrance proved to be one of the harder working team members but was hindered by his footwear. Without his high altitude boots he was limited to staying below 20,000 ft. Even with staying at the lower camps Durrance’s feet were taking a beating and hindering his productivity.

The second event was one that had the expedition not ended in disaster probably would have gone unnoticed. When Wiessner and Wolfe were gathering the supplies for the expedition they did not purchase enough snow goggles for the porters. Expedition members created makeshift glasses by cutting narrow slits into pieces of cardboard. Shortly after beginning the days march toward K2 three porters suffered from snow blindness. The three were sent back to Askole and their loads were divided between Cranmer, Durrance, Sheldon, and Trench. The extra weight effectively created a double-carry for the four.

The third event would weaken the expedition’s manpower by one sixth. On May 30th, Cranmer spent some time in a crevasse trying to retrieve a tarpaulin that was dropped by one of the porters. Cranmer emerged with the tarpaulin but also severely chilled and exhausted. Cranmer then carried the extra weight from the loss of porters to snow blindness on May 31st adding even more exhaustion. Cranmer rose from his tent on June 1st to announce that he did not feel well before he retreated back inside. Hours later, Cranmer would be coughing up more than three coffee cups worth of a, “clear, frothy fluid” and was slipping in and out of states of delirium and consciousness. Years later Durrance stated, “I never knew anyone could be so sick and stay alive.”

Now at the mountain and before committing to the difficult climbing on the Abruzzi Ridge, Fritz and Cromwell took a day to get a view of northeast ridge. But as it was in 1938, no viable route presented itself. So, the Abruzzi Ridge was the route to the summit. Loads were carried and routes established following the footsteps of the year before. To avoid the dangers of rock fall Camp III (20,700 ft.) was used only as a supply cache.

As the route progressed upward, almost exclusively led by Wiessner, morale began to decline. Storms battered the expedition and battered ambition. A chasm was beginning to open in the expedition, one of motivation and physical distance. Wiessner and Wolfe never wavered in their ambition or optimism of reaching the summit, while the rest of the members seemed to grow lethargic and hesitant to continue pushing up the mountain. Wiessner and Wolfe continued up while the majority of the expedition tended to stay in the lower camps with Durrance typically somewhere in between.

The battering storms that weakened morale also made a physical impact on the team. The cold of the storms nipped Sheldon’s toes. Sheldon continued working on the mountain until the weather improved. With the arrival of warmer weather his feet began to swell and he could do little more than hobble, which he did down to basecamp. Physically, two of the six of the expedition members were incapacitated.

The 1939 expedition would establish two camps higher than the previous year. Camp VIII was established at 25,300 ft. and Camp IX at 26,050 ft. Both were stocked well enough to support a push to the summit. July 18th saw an attempt for the summit from Camp IX by Wiessner and Lama. Meanwhile, Wolfe was well supplied but alone at Camp VIII. Durrance, the closest American to Wolfe was at Camp II (19,300 ft.).

It was a harrowing attack that brought the pair to 27,500 ft. just 700 ft. from the summit. Wiessner wanted to continue upwards but Lama did not. The time was 6:30 p.m. and proceeding upward would mean descending at night. Wiessner saw the route that lay ahead and was confident they would be able to reach the summit on the second attempt.

On the retreat to Camp IX, Lama’s crampons that were strapped to his pack became tangled in rope and ended up being lost. On the second attempt the loss of crampons came into play. In order to ascend without crampons step cutting became necessary and it was apparent that the task would take too long. So the team descended again, this time to Camp VIII, to restock.

Jack Durrance Collection

Wolfe informed the pair upon their arrival that no loads from below came up during their absence. This left the provisions at Camp VIII too little to support another summit attempt and another descent was made. Now a trio, Wiessner, Lama and Wolfe made their way to Camp VII. What was found at Camp VII was devastating and exacerbated by a fall that Wolfe had taken en route where he lost his sleeping bag. The majority of the supplies at the camp had been stripped leaving the trio with one air mattress and one sleeping bag.

With much frustration and confusion about their current situation, Wolfe would remain at Camp VII while Wiessner and Lama would continue downward to Camp VI. A deserted Camp VI saw the duo continue downward only to find empty camps littering the route. After an awful night’s sleep wrapped in a tent at Camp II, Wiessner and Lama made their way into basecamp exhausted and suffering from the cold. There would be no more attempts for the summit.

Wolfe still lay alone 24,000 ft. and Durrance, Dawa, Phinsoo and Kitar started up to retrieve him. On July 25th they ascended to Camp IV. Durrance and Dawa were ill the next day so Phinsoo and Kitar continued on the Camp VI. Camp VI also saw the arrival of Kikuli and Tsering who in a single day ascended from basecamp, 6,900 ft. below! The first contact with Wolfe on July 29th found him in dismal condition. He convinced his rescuers to come back for him on the morrow when he would be ready.

Poor weather delayed their second attempt until July 31st. With the weather still poor Kikuli, Kitar and Phinsoo went to retrieve Wolfe. On August 2nd Tsering returned to basecamp alone. He relayed the previous days’ activities and that he hadn’t seen or heard from the neither three Sherpa nor Wolfe since the second attempt to retrieve Wolfe departed Camp VI.

One more attempt was made to reach the high camps to see if there was any sign of life high up on the mountain, but Camp II would be the highest they could reach. On August 9th Kikuli, Kitar, Phinsoo and Wolfe were presumed dead and the expedition departed from K2.

Pasang Kikuli. Jack Durrance Collection

Read about the 1938 Reconnaissance of K2 here.

Read about the 1953 Third American Karakoram Expedition here.

*Photos from the Jack Durrance Collection restored by The Photo Mirage Inc.

By Eric Rueth

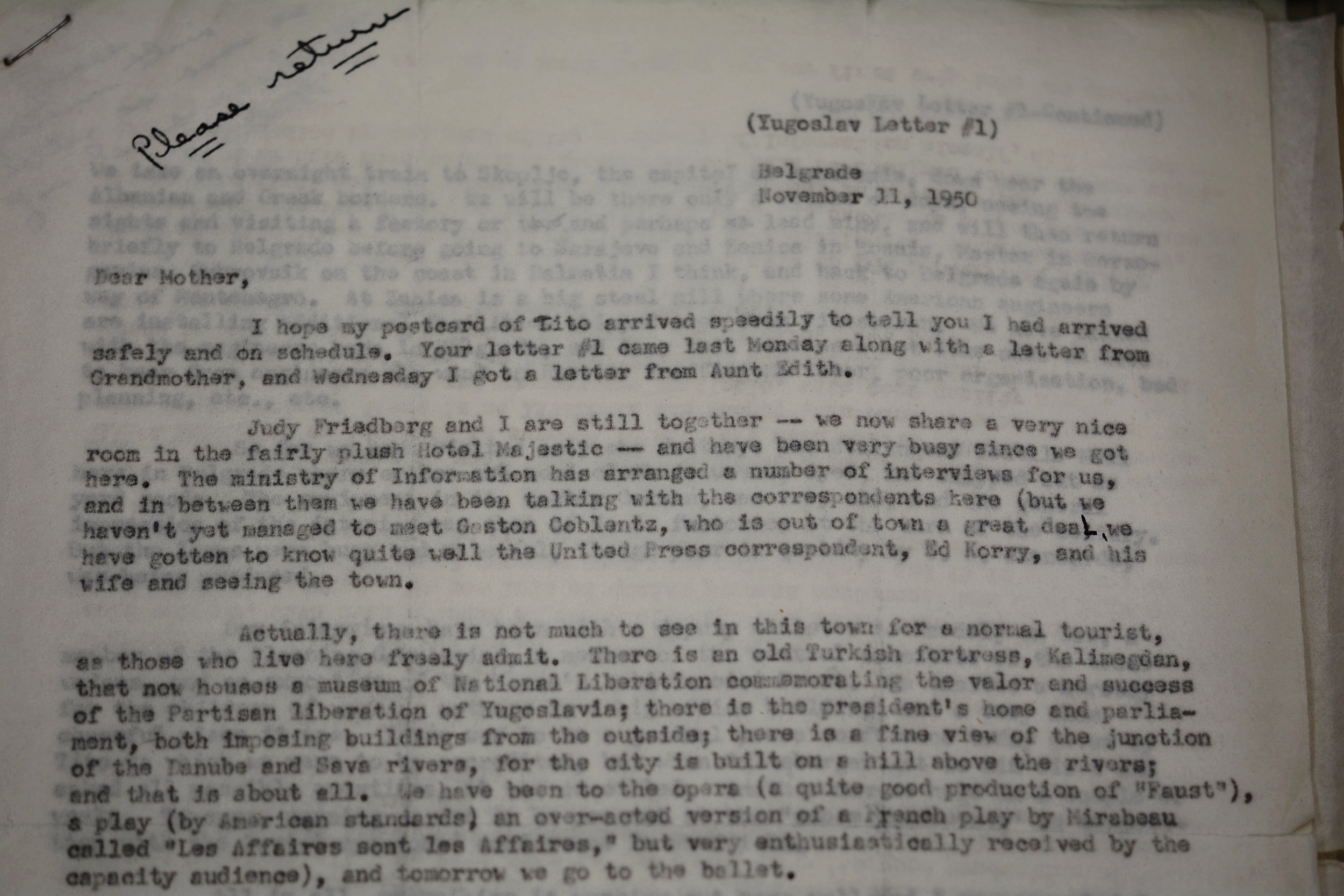

Elizabeth Hawley 1923 – 2018

Elizabeth Hawley, known as the Chronicler of the Himalayas, kept meticulous records of climbs in the Nepalese Himalaya for over half a century. Those records make up the Himalayan Database. She was a remarkable woman and will be missed.

Miss Hawley has donated her archives to the American Alpine Club Library, where they will be preserved for future generations. Already residing in the archives are Miss Hawley's correspondence, postcard collection and the newly arrived 1963 American Everest File. Her files and personal library collection will arrive in the coming months.

Below you will find tributes from Lisa Choegyal, good friend of Miss Hawley, and Richard Salisbury, friend, co-author and builder of the Himalayan Database.

By Lisa Choegyal

Nepali Times

Elizabeth Hawley, who died in Kathmandu on 26 January 2018 aged 94 years, was an American journalist living in Nepal since 1960, regarded as the undisputed authority on mountaineering in Nepal. Born 9 November 1923 in Chicago, Illinois and educated at the University of Michigan, she was famed worldwide as a “one-woman mountaineering institution”, systematically compiling a detailed Himalayan database of expeditions still maintained today by her team of volunteers, and published by the American Alpine Club.

Respected for her astute political antennae and famously formidable, Miss Hawley represented Time Life then Reuters since 1960 as Nepal correspondent for 25 years. She is credited with mentoring reporters and setting journalistic standards in Nepal, competing to file stories from the communications-challenged Nepal of the 1960s. She worked with the pioneer adventure tourism operators, Tiger Tops, from its inception in 1965 with John Copeman, until she retired as AV Jim Edward’s trusted advisor in 2007.

For Sir Edmund Hillary, she managed the Himalayan Trust since it started in the mid-1960s, dispensing funds to build hospitals, schools, bridges, forest nurseries and scholarships for the people of the Everest region. Generations of Sherpas remember being overawed by the rigor of Miss Hawley’s interviews, and quake at the memory of her cross-examinations when collecting their scholarship funds. Sir Edmund Hillary described Elizabeth Hawley as “a most remarkable person” and “a woman of great courage and determination.” She served as New Zealand Honorary Consul to Nepal for 20 years until retiring in 2010.

Elizabeth first came to Nepal via India for a couple of weeks in February 1959. She was on a two-year round the world trip that took her to Eastern Europe, the Middle East and South Asia. Bored with her job as researcher-reporter with Fortune magazine in New York, she had cashed her savings to travel as long as they lasted. Nepal had been on her mind since reading a 1955 New York Times article about the first tourists who visited the then-Kingdom.

Because of her media contacts, the Time Life Delhi bureau chief asked her to report on Nepal’s politics. It was an interesting time - as one of only four foreign journalists, she was present when King Mahendra handed over the first parliamentary constitution, which paved the way for democracy in Nepal. Fascinated by Nepal’s politics and the idea of an isolated country emerging into the modern 20th century, she returned in 1960 and never left, living in the same Dilli Bazaar apartment, the same powder blue Volkswagen beetle car, and generations of faithful retainers.

A diminutive figure of slight build with a keen look, Elizabeth was bemused at the universal attention she received. Her Himalayan Database expedition records are trusted by mountaineers, newswires, scholars, and climbing publications worldwide, published by Richard Salisbury and the American Alpine Club. She was one of only 25 honorary members of the Alpine Club of London, and has been formally recognized by the New Zealand Alpine Club and the Nepal Mountaineering Association. In 2004 she received the Queen's Service Medal for Public Services for her work as New Zealand honorary consul and executive officer of Sir Edmund Hillary’s Himalayan Trust. She was awarded the King Albert I Memorial Foundation medal and was the first recipient of the Sagarmatha National Award from the Government of Nepal.

Elizabeth’s career in the collection of mountaineering data started by accident: “I’ve never climbed a mountain, or even done much trekking.” As part of her Reuters’ job, she began to report on mountaineering activities and in those pioneering days of first ascents and mountain exploration, there was strong media interest in Himalayan expeditions. She relied heavily on the knowledge of mountaineer Col Jimmy Roberts, founder of Mountain Travel.

Since 1963 she has met every expedition to the Nepal Himalaya both before and after their ascents, including those who climbed from Tibet. Her records contain detailed information about more than 20,000 ascents of about 460 Nepali peaks, including those that border with China and India. Over the course of some 7,000 expedition interviews, her research work has sparked and resolved controversies. Elizabeth has seen the Nepal mountaineering scene transformed from an exclusive club to a mainstream obsession.

Elizabeth did not suffer fools gladly. Though some mountaineers were intimidated by her interrogations - sometimes jokingly referred to as an expedition's "second summit," - serious alpinists greatly admired her. "If I need information about climbing 8,000-meter peaks, I used to go to her," says Italian climbing legend Reinhold Messner. Nepali trek operator and environmentalist Dawa Steven Sherpa underlines the point: "Although it's the authorities that should have been doing this, they're not as strict or accurate as Miss Hawley. One of her biggest contributions is keeping mountaineers honest."

Elizabeth applied her trademark scrupulous precision to summarizing the political and development events in Nepal in her monthly diary, published in 2015 in two volumes as “The Nepal Scene: Chronicles of Elizabeth Hawley 1988-2007”. They stand as a faithful and unique historical record of the extraordinary changes that took place in Nepal over nearly two decades.

Her enviable journalistic sources were based on long friendships with the political, panchayat and Rana elite. She had the confidence of a wide range of prominent Nepalis, and shared a hairdresser with the (then) Queen. Educated as an historian, Elizabeth regarded herself as a reporter not a writer, stringently recording Nepal’s political and mountaineering facts with minimal opinion or analysis. Although there is no disguising her liberal bent and her admiration for the force of democracy. Former American Ambassador Peter Bodde said, Elizabeth Hawley was one of Nepal’s “living treasures” and “her contribution to the depth of knowledge and understanding between Nepal and the US was immense.”

Elizabeth Hawley’s achievements have featured in many books and articles about Nepal, and her biography by Bernadette McDonald, I’ll Call You in Kathmandu, was published in 2005, then updated and reprinted as Keeper of the Mountains. In 2013, to mark the 60th anniversary of the first ascent of Everest, Elizabeth was featured in the award-winning US television documentary of the same name, produced by Allison Otto. On screen in Keeper of the Mountains, her straightforward manner and fearless modesty made her something of a cult classic. In 2014 the Nepal government named a 6,182 meters (20,330 feet) peak in honour of her contribution to mountaineering. Elizabeth was not impressed:

"I thought it was just a joke. Mountains should not be named after people."

Miss Elizabeth Hawley is the last of the first generation of foreigners who made their life in Nepal, single and determinedly independent. She is survived by her nephew Michael Hawley Leonard and has bequeathed her library and records to the American Alpine Club. As both a successful woman in a man’s world and a highly visible foreigner recording Nepal’s history, we are all in her debt. She defied the conventions of her time, and determined to live life on her own terms and in her own incomparable style.

Elizabeth Hawley and the Himilayan Database

Remembrance of Elizabeth Hawley from Richard Salisbury, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 4 February 2018

I first met Liz Hawley in 1991 as the leader of the American Annapurna IV expedition when she came to interview me at the Malla Hotel. She was armed with the results of all of the previous expeditions to Annapurna IV, while I had prepared a spreadsheet taken from past American Alpine Journals showing the arrival and summit dates of the previous teams in order to make an estimate of the amount of supplies that would be needed for the climb.

Given what we both had, I suggested to Liz that we collaborate on building a database for her records. Liz initially declined saying that she was already working with a Nepali computer student to do this. But a year later in 1992, she contacted me telling me that her student had run off to graduate school in Arkansas and probably would never return to Nepal.

Thus began a multi-year project to design and enter her records into the database that the American Alpine Club published in 2004 as the Himalayan Database. Over 10,000 hours were spent entering the vast amount of information Liz had collected and stored in her wall-to-wall cabinets since she met the first American Everest expedition in 1963.

When the database was published, I hoped that we might be able to continue updating for 4 or 5 years, as Liz was then 80 years old. But Liz continued to thrive and we kept going strong ever since keeping the database up-to-date with all of the new teams coming to Nepal. With Billi Bierling now at the helm, we expect to continue for many years into the future.

I feel blessed to have had such a wonderful working relationship with Liz for 25 years and will greatly miss seeing her when I again come to Kathmandu later this year.

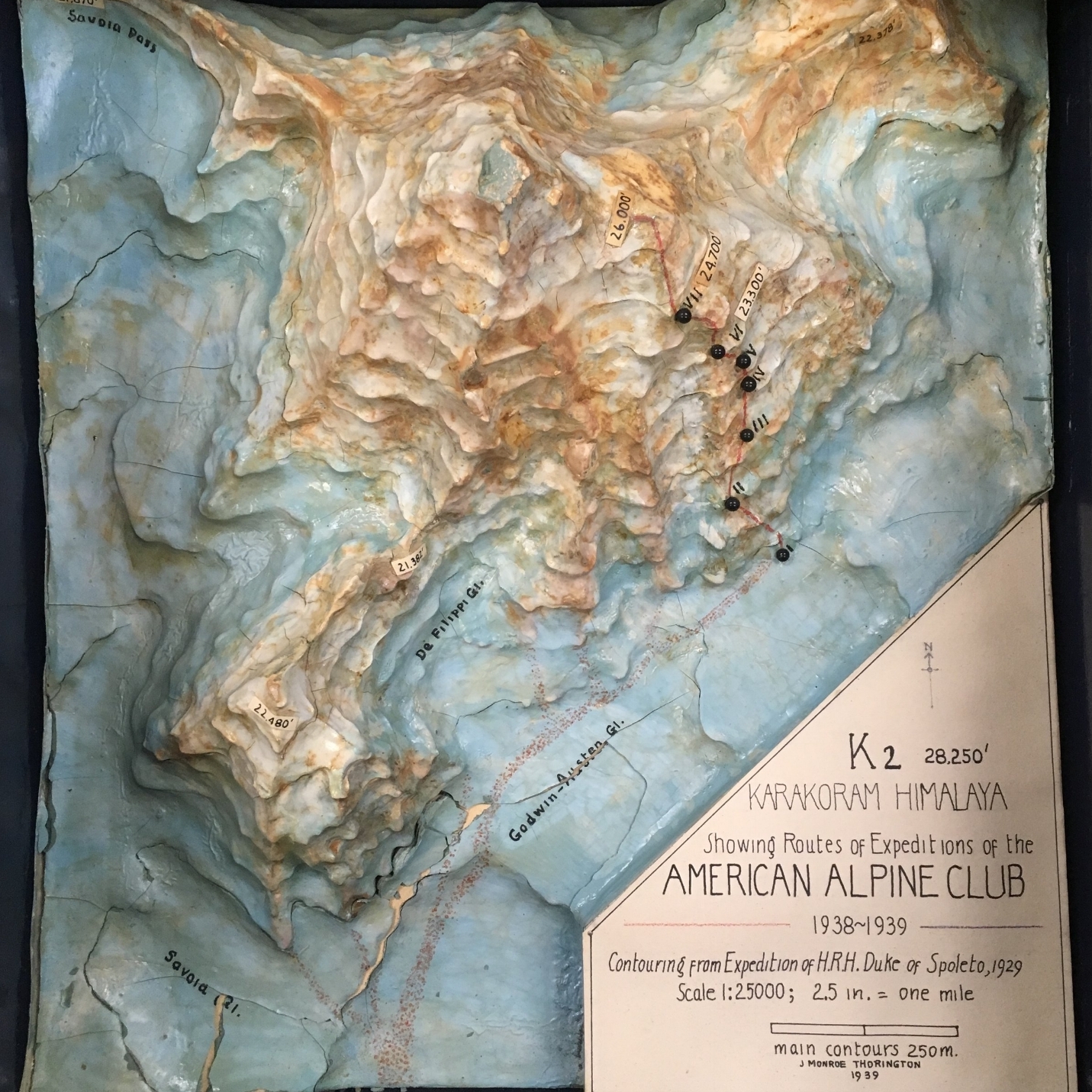

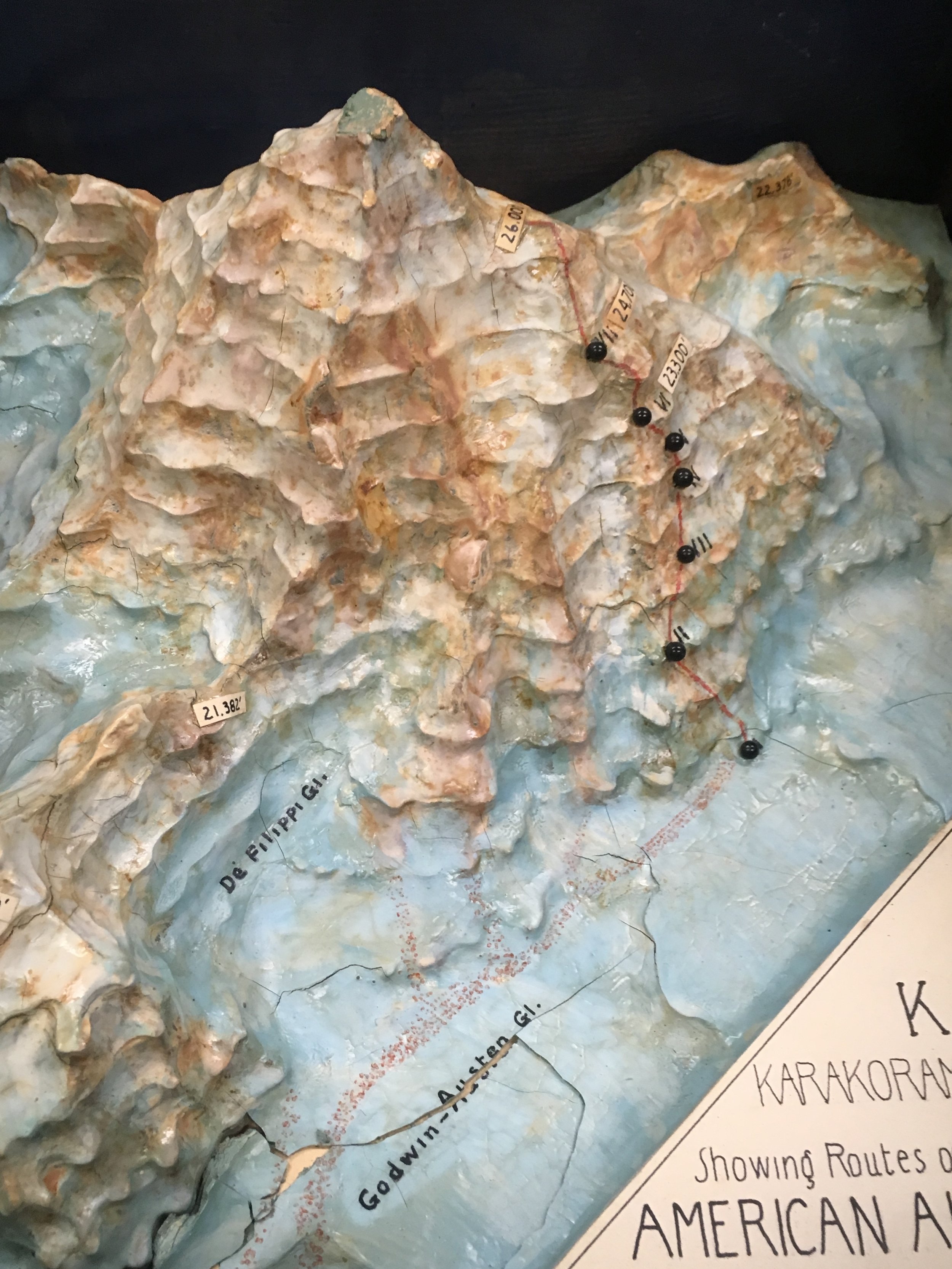

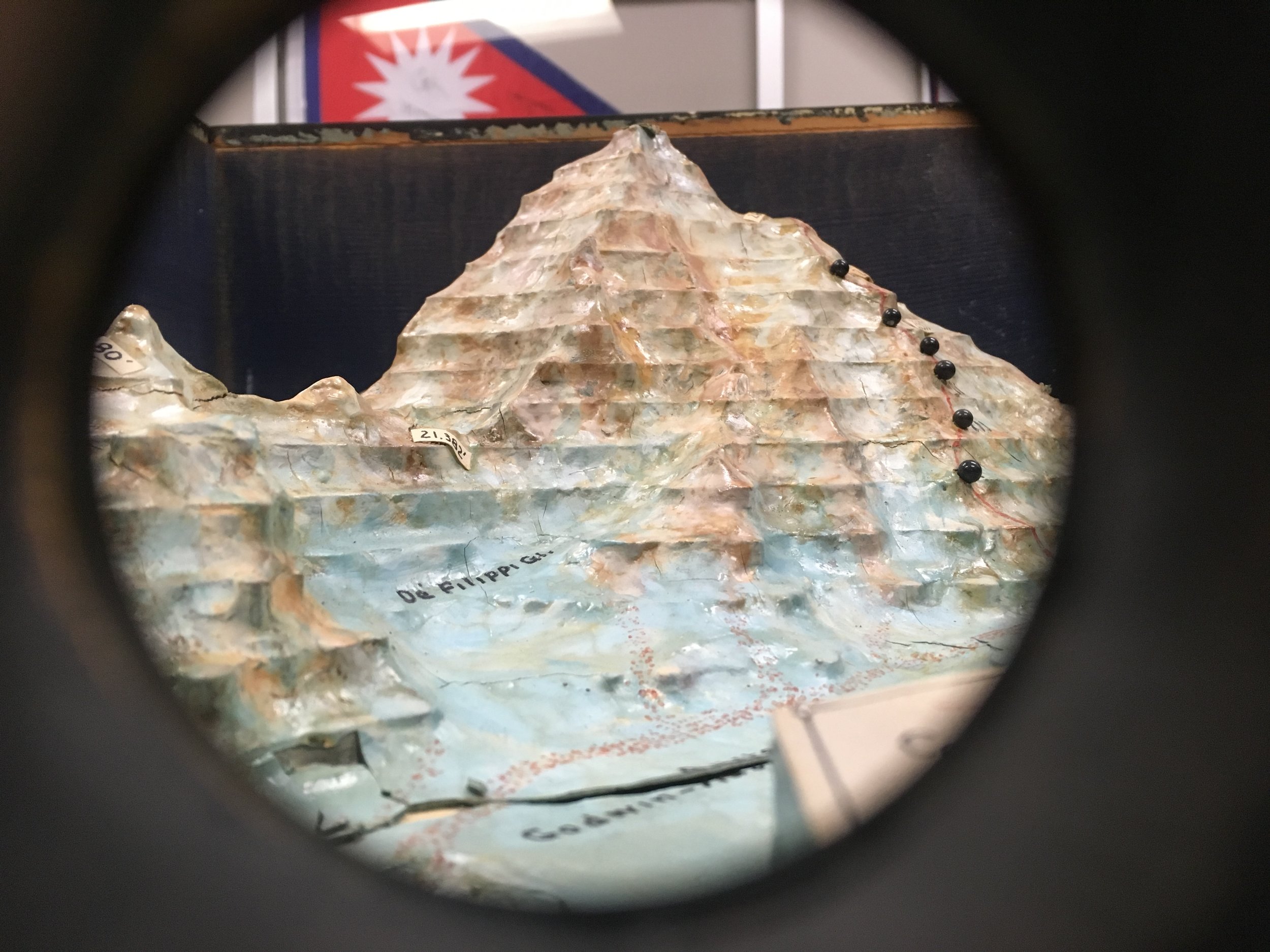

K2 1938: The First American Karakoram Expedition

by Eric Rueth

On February 24, The American Alpine Club will celebrate the first American ascent of the world’s second-highest peak, K2, at our Annual Benefit Dinner in Boston. It’s been 40 years since Jim Whittaker led an American expedition to the Savage Mountain but the history of American expeditions to the mountain goes back much farther and is one mired in adventure, tragedy and heroism.

Photograph of K2 from the Baltoro Glacier, taken by Vittorio Sella in 1909. Vittorio Sella Collection

The first American expedition to K2 took place in 1938. This was not only the first American expedition to the mountain but the 3rd ever attempt on the mountain and the first since the Duke of Abruzzi attempted K2 in 1909. The American Alpine Club had acquired permits to K2 for 1938 and 1939. With permits for back-to-back years, the main focus for the 1938 expedition was to reconnoiter the mountain and three ridges to determine the best route to the top. Of course if the opportunity presented itself they should reach the summit.

After evaluating photographs and surveys of the area from previous expeditions, it was determined that there were five potential routes. This meant there were five routes that had to be explored and hopefully at least one with a viable route to the summit.

The party, given the task that was laid before them, was relatively small. It included Charles Houston, Robert Bates, Paul Petzoldt, Richard Burdsall, Bill House, Captain Norman Streatfeild (British Liaison Officer), 6 Sherpa porters and 3 camp men.

On May 13, 1938 the party departed Srinagar to begin their 362-mile approach. After a month the confluence of the Savoia and the Godwin-Austen glaciers was reached on June 12. The confluence of the glaciers provided a centralized basecamp that allowed the expedition to have relatively easy access to both glaciers for reconnaissance.

Once base camp was established at 16,600 ft., the first task was to reconnoiter the Northwest Ridge. The ridge looked promising in photographs taken by the Duke of Abruzzi’s expedition, and two of his guides had reached the Savoia Pass on the ridge. After navigating over the crevasse covered glacier, Houston and House reached the bergschrund only to find disappointment in the form of hard green ice. It was fewer than 800 feet to better terrain above but they determined that chopping steps into the ice would be too consuming of time and energy and would be a dangerous link in the chain of camps up the mountain if the Northwest ridge offered a viable route. Fortunately, Petzoldt and Burdsall spied a rock route that they believed could unlock the ridge. When House and Petzoldt made an attempt to see if the rock route would go, they were met with unfavorable weather and had to abandon the thought for the moment.

On June 19th the entire party convened at basecamp to discuss what had been discovered thus far and how to proceed. Bates and Burdsall had made a trip down the Godwin-Austen Glacier and through brief clear weather windows were able to completely rule out the south face due to avalanche danger. After a good look at the Abruzzi Ridge, they reported that it didn’t look promising.

The northwest ridge wasn’t out of the question, but the obstacle of ice would be a time consuming one. So, the focus shifted to the east side of the mountain. The expedition would get a close look at the Abruzzi Ridge and the northwest ridge and return to the Savoia glacier if no route seemed better than what had already been discovered on the northwest ridge.

Continuing with the trend, the first views from the east side of K2 were not positive. The northeast ridge is a long knife-edge ridge littered with gendarmes. The south side of the ridge seemed like it could go but would require long stretches of travel through icy gendarmes that could topple over onto anyone traveling beneath them. The north side was prone to avalanches from high up the mountain and neither appeared to offer sites suitable for establishing camps. The Abruzzi Ridge at least looked possible, though difficult.

After the first views of these two ridges it was decided that Houston and House would climb the Abruzzi Ridge to determine the difficulty of climbing. On the first day of exploration of the ridge Houston discovered some small pieces of wood, these were remnants of the Duke of Abruzzi’s highest camp in 1909 and provided a psychological boost to the climbers. As they carried on up the ridge, the climbing grew more difficult and no suitable campsites were found. With the Karakoram’s penchant for sudden poor weather, the lack of adequate campsites was more concerning than the difficulty of climbing.

Photograph of K2 from Windy Gap, taken by Vittorio Sella in 1909. Vittorio Sella Collection

Uncertainty began to set in. Three routes remained as options: the northwest ridge, the northeast ridge and the Abruzzi Ridge. The big problem was that none of the routes seemed particularly better than the others. Each ridge had its own question looming over it. Could the northwest ridge be reached without devoting a lot of time and energy to carve out steps? Was there a potential route hidden on the northeast ridge that would not place the climbers in extreme danger? Were there any suitable locations to place campsites on the Abruzzi Ridge?

The party attempted to answer two of these questions. Bates and House returned to the Savoia Glacier. A few days of roaring avalanches off of the west face of K2, tumbling seracs, traversing ice slopes and heavy snow saw the pair reach a high point of 20,000 ft. before the rock became too steep. They came to the conclusion that reaching the northwest ridge under the current conditions was not possible.

Houston and Streatfeild had an easier time on the northeast ridge; easier in that they realized after several hours of step cutting that the route would not be adequate for carrying loads and the ridge offered little protection for any campsites that could be established.

So the Abruzzi Ridge was all that remained. As the last viable option all efforts and resources would now focus on the Abruzzi Ridge. Camp I was established at its base at 17,700 ft. While the rest of the expedition ferried loads to stockpile Camp I, Petzoldt and House continued scouring the ridge for campsites. After a day of searching and ascending a steep snowfield, hopes were waning and the pair was about to descend back to Camp I. Petzoldt decided to ascend one more pitch to peek around the corner of a crest. When Petzoldt reached the end of the rope, he let out an excited yell. Camp II was found. The campsite at 19,300’ was the first good news of the expedition since arriving the base of the mountain and lifted everyone’s spirits.

Rock taken from the Abruzzi Ridge. Karakoram translates to, "black gravel." Robert H. Bates Collection

Once Camp II was established and stocked with 10 days worth of supplies Petzoldt and House again led the way in search of the next camp. The ground grew steeper and steeper with any ledges discovered sloping downward. Once again the prospect of finding a campsite seemed slim and hopes began to waver. Around noon, as the going became more and more difficult, the pair noticed two buttresses a few hundred feet above them that may yield suitable terrain. With haste House began the first of two ice traverses that lay between them and the buttress. In an effort to save time House cut as few steps as possible. This time-saving maneuver led to House losing purchase and sliding towards the Godwin-Austen Glacier. Petzoldt was prepared for this possibility and held fast to the rope around House’s waist. After banging into the buttress that Petzoldt belayed from, House attacked the ice slope with new vigor. House completed the traverse placing pitons and running rope along the way. The reward for the day’s climbing was a tiny, uneven platform that sloped off the mountain on three sides.

Before Camp III (20,700 ft.) could be established Petzoldt and House needed to safeguard the route with 900 ft. of rope. The treacherous terrain was difficult for two unloaded men; it would be near impossible and reckless to attempt with a full load of supplies. The task of safeguarding the route took the entirety of the next day and still not satisfied with its security, was reinforced more as light loads were carried towards Camp III the day after that. Before the light loads could be brought all the way to Camp III, a storm began to build. The loads were left below a buttress and the pair descended all the way to Camp I when it appeared that the storm was gaining strength and was potentially going to be a long one.

The storm was not prolonged and the next day was relatively clear. With extreme caution, loads were carried to Camp III and more ropes placed to further secure the treacherous sections of the route. After 4 days of ferrying loads while snow fell and winds howled around them it was time to go higher than Camp III and search for Camp IV.

Petzoldt and Houston led the way in search of Camp IV. The climbing above Camp III grew more technical, the rock grew more rotten and was eventually blocked by a large gendarme. Petzoldt conquered the obstruction via an overhanging crack that led to a ledge with solid holds. A few hundred feet above the recently defeated gendarme another obstruction was reached, this time it was an impassable wall of reddish-brown rock. The duo descended back to the top of the gendarme and decided that it would be the location for Camp IV (21,500 ft.).

Once Camp IV was established it was time to push up the mountain. The new leaders were Houston and House. A location for Camp V was discovered at 22,000 ft., placing it only 500’ higher than Camp IV.

Above Camp IV the rock was near vertical and in worse condition than expected. This section was only climbed after House was able to work his way up an 80-foot chimney. The chimney now bears his name. Camp V was then located across a snowfield and under a rock pinnacle. This 500’ took four hours to achieve and would be an entire days work when moving supplies. House’s Chimney was impossible to climb with a load so a makeshift aerial tramway was constructed to haul the loads up.

After a few days of poor weather and load ferrying, a site for Camp VI was discovered at 23,300’. The climb up to Camp VI took serious skill in route finding and saw Petzoldt and Houston turned back at multiple points. Eventually they discovered a steep snow gully that tested their nerves. The snow was deep and anything that fell down the gully disappeared into nothingness. The snow gully led to more rotten rock, which led to a buttress whose base would be the location for Camp VI.

Above Camp VI lay the black pyramid, a near 1,000-foot buttress of dark rock that loomed over the expedition while they were scouting the ridge a month earlier. If they could make their way up the black pyramid, K2’s 2,200-foot summit cone would be within reach.

Petzoldt and Houston worked their way up the route; Petzoldt, with fine intuition about where the path lay ahead, led over steep technical rock and eventually up another snow gully that led to the top of the pyramid. With the snow shoulder above the black pyramid reached, the Abruzzi Ridge was conquered. A handshake was shared and a “restful cigarette” enjoyed.

Thank you note written by Houston and Petzoldt on a piece of toilet paper. It reads:

"Hi

Thanks a million for the campsite and tent. They were certainly welcome when we came down at 4:15. Very cold.

We went 700 ft. higher over climbing of varying difficulty and spotted c/c weather. Route ahead not too bad. Hope to make top of pyramid today.

We hoped you could make two platforms more on this ledge and one near the big notch [?] feet below here.

Good luck + thanks again

C +P"

Robert H. Bates Collection

The route was pushed higher and a good campsite was found for Camp VII at 24,700 ft. Even after ropes were fixed on the difficult terrain between Camp VI and VII, the route would remain difficult and would be unwise to attempt in bad weather. With supplies dwindling it was time to make a decision.

The expedition conceded to K2 and the mountain remained unclimbed. With supplies dwindling and difficult terrain between camps a prolonged storm would potentially be catastrophic to the group, added onto that the porters were due to arrive in seven days.

Before retreating down the mountain, one final push would be made. Houston and Petzoldt would make a dash as high up the mountain as they could reach. A Spartan Camp VII was established with just enough supplies for Houston and Petzoldt to climb for a day. Any sign of bad weather would force the pair to make a hasty retreat to Camp VI.

The weather the next day was clear so the pair went up. Though K2 had provided many difficult and technical days of climbing, the final day was one of plodding through snow. By noon a recognizable shoulder was reached at 25,600 ft. The Duke of Abruzzi had triangulated the altitude 29 years earlier and the climbers knew that they had reached the summit cone. The pair climbed up a few hundred more feet to gain a good view of the route that led to the summit. Both agreed that it did not appear any more difficult than the route below and that the summit could be reached from the Abruzzi Ridge. They then turned and started back down the mountain.

Though their high point of 26,000 ft. was 2,250 ft. below the summit, the First American Karakoram Expedition was a success. The entire south side of the mountain was reconnoitered and a promising route to the summit was discovered. More importantly there were no major injuries and everyone involved survived the attempt high up the Savage Mountain. It was now up to the Second American Karakoram Expedition to climb the mountain.

Read about the Second American Karakoram Expedition here.

Read about the Third American Karakoram Expedition here.

By Eric Rueth

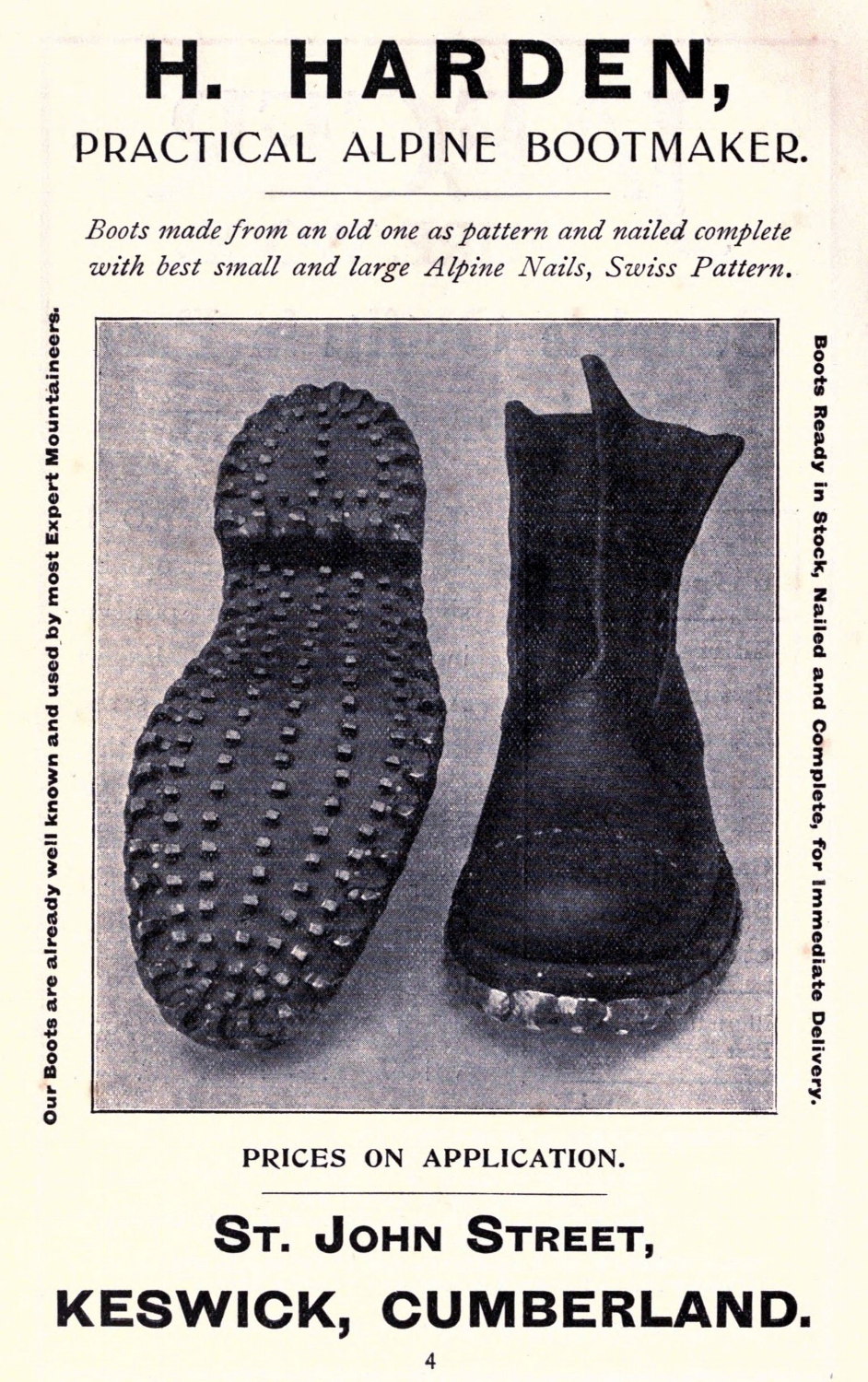

Mountaineering Boots of the early 20th century

A tale of horror and woe

by Allison Albright

Modern mountaineering boots are made to be comfortable, lightweight, insulated and waterproof. They're constructed of nylon, polyester, Gore-Tex, Vibram and involve things like "micro-cellular thermal insulation" and "micro-perforated thermo-formable PE." This technology costs anywhere from a couple hundred dollars to over $1000 and makes it much more likely for a mountaineer to keep all their toes.

We didn't always have it so good.

Mountaineering boots circa 1911.

By H. Harden - Jones, Owen Glynne Rock-climbing in the English Lake District, 1911, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9433840

Early mountaineering boots were made of leather. They were heavy, and to make them suitable for alpinism it was necessary for climbers to add to their weight by pounding nails, called hobnails, into the soles.

“The very best boot is without a doubt the recognized Alpine climbing boot. Their soles are scientifically nailed on a pattern designed by men who understood their business; their edges are bucklered with steel like a Roman galley or a Viking’s sea-steed. No doubt they are heavy, but this slight inconvenience is forgotten as soon as the roads are left.”

Tricouni nails were a recent invention in 1920 and could be attached to mountaineering boots to provide traction. They were specially hardened to retain their shape and sharpness.

Illustration from Mountain Craft by Geoffrey Winthrop Young. New York, 1920.

Illustration of boot nails from Mountaineering Art by Harold Raeburn, 1920.

In 1920 a pair of climbing boots went for about £3.00 - the equivalent of $28.63 in 2017 US dollars. However, climbers got much less for their money than we get out of our modern boots.

Original hobnails, stored in a reused box

“There is no use asking for “waterproof” boots; you will not get them.”

In addition to being heavy, the boots were not waterproof. Mountaineers had to apply castor oil, collan or melted Vaseline to the boots before each trip. This kept the boots flexible and also kept at least some water out. Animal fats were also an option, but they had a strong, unpleasant smell and would decompose, causing the leather and stitching of the boots to rot as well.

Hobnail boots

in action on Mumm Peak, Canada. 1915

Photo from our Andrew James Gilmour collection.

Boots with linings were not recommended for mountaineering, as the linings were usually made of wool and other natural fibers which were slow to dry when inside a boot. Wet boot linings, either due to water or snow leakage or human sweat, were a major cause of frostbite resulting in the loss of toes.

When not in use, the boots needed to be stuffed with dry paper, hay, straw or oats which were changed at intervals to ensure that all moisture was absorbed. If they weren't stuffed in this manner on an expedition, they were in danger of freezing and twisting out of shape.

A pair of worn hobnail boots set to dry over a fan in about 1920. This luxurious set-up was possible because the mountaineer was staying in a Swiss hotel.

Photo from our Andrew James Gilmour collection.

“Look with suspicion upon the climber who says he wears the same pair of boots without re-soling for three or four years. It will probably be found that his climbing is not of much account, or he is wearing boots which have badly worn and blunted nails, with worn-out and nail-sick soles, a worse climbing crime if he proposes to join your party, than if he were to wander up the Weisshorn alone.”

Crampons

Today crampons are made of stainless steel and weigh about 1 to 2 lbs. They can be bolted or strapped to the boot. In the early 20th century, crampons were made of steel or iron. They were strapped to the boot with hemp or leather straps passed through metal loops attached to the frames. Surprisingly, they didn't weigh too much more in the 1920s than they do today.

They could be bought in a variety of configurations, including models ranging from four to ten spikes. Mountaineers who recommended their use wrote that good crampons should have no fewer than eight spikes which should not be riveted to the frame. The crampons also should not be welded anywhere and the iron variety were likely to break if any real work were required of them.

A steel crampon with eight spikes and hemp and leather straps - ideal!

From the American Alpine Club Library archives

Good footwear is still one of the most important aspects of any trip. We're extremely grateful boot technology has advanced so much.

Care and Handling of Archival Nitrate Negatives

by Allison Albright

Nitrate film base was developed in the 1880s and was the first plasticized film base available commercially. It enabled photographers to take pictures under more diverse conditions, and its flexibility and low cost was partially responsible for making photography affordable and accessible to amateur consumers as well as professionals. It was widely used from the 1890s until the 1950s.

An album of nitrate negatives circa 1900

Nitrate negatives also happen to be mildly toxic and somewhat volatile. Because the material is the same chemical composition as cellulose nitrate (also known as flash paper or guncotton), which is used in munitions and explosives, it is incredibly flammable and prone to auto-ignition. It was also used in motion picture film in the early 20th century and was responsible for several movie theater fires during that era.

Below are some negatives in the early stages of deterioration.

As if the danger of combustion wasn’t enough, nitrate negatives also emit harmful nitric acid gas as they deteriorate, meaning that we need to use safety precautions such as respirators and latex gloves when handling these negatives.

HNO3 + 2 H2SO4 ⇌ NO2+ + H3O+ + 2HSO4

Nitric acid is considered a highly corrosive mineral acid.

Nitrate negatives usually deteriorate in just a few decades, making them an extremely unstable storage medium. As they deteriorate, the image begins to fade and the negative turns soft and gooey, causing it to weld itself to whatever it’s stored with, resulting in the loss of the image.

A clump of badly deteriorated negatives stuck together forever

When good negatives go bad - a negative in the process of becoming goo

Like most archival collections containing materials created from about 1890 to the early 1950s, the AAC’s collection includes some nitrate film negatives. For most of their lives, these negatives have been stored in a cold, temperature controlled area. We’re digitizing these negatives in order to capture the images and make them accessible to the public before we put them in deep freeze. The best way to preserve and store nitrate negatives for the long term is to freeze them to slow the process of deterioration and minimize the risk that they’ll start a fire.

Because of the unstable nature of nitrate negatives, some deterioration is to be expected. However, the vast majority of this collection is still in good shape. We've included a few selections below. Eventually, we’ll make all the images from our nitrate negatives available.

These photographs are taken from the collection of Andrew James Gilmour (1871-1941), an AAC member whose surviving photographs help inform our knowledge of the history of climbing and what the sport was like in the early 20th century.