Evan Hau is a pro climber, but most Americans still don’t know his name. He’s the first Canadian to climb 5.15a, and swears his success comes from consistently honing his strengths (and mostly ignoring his weaknesses). In this episode, we chat about how he balances pushing his limits, with his tutoring business, and the process of climbing his first 15a, Sacrifice. We cover the magic of the Bow Valley—the epic limestone crags near Canmore, Alberta—as well as what happens when Adam Ondra comes to town to try to flash your proj. We discuss trying hard on long trips, and his send of Death of Villains last year, his second 15a. Plus, we chat about aging as a climber, with his 40th birthday just around the corner.

The Prescription—Ground Fall

It’s February, and yours truly is bouldering in sunny Hueco Tanks, Texas. I was reminded a few weeks ago that all climbing is not without risk, when a close friend fractured his ankle bouldering in the park and had to be extracted by SAR. The situation was compounded when a rescuer fell off the low-fifth-class approach and also required extraction.

This accident, like the one featured below, happened despite the fact that everyone was playing by the book. In the accident below, two apparently textbook cam placements failed when the leader applied body weight to the top cam on a lead of a slippery granite crack. More serious injury was prevented because the climbers in question had built a solid belay anchor on the ledge below, and the leader and the belayer were both wearing helmets. Still, this is a case in point that you can do everything right and still end up in the hospital.

The Metolius TCU is an old version with all cam lobes an equal width. Later, the single middle lobe was widened to provide more opposing surface area. The U-stem Black Diamond Camalot Junior is from the mid-1990s. This version’s cam lobes were fabricated from very hard 7075-T6 aluminum—a material implicated in several incidents in which the cam lobes tracked out of apparently perfect placements. Both models of gear have been improved over the decades and form the backbone of many standard trad climbing racks.

Ground Fall | Multiple Pieces of Protection Pulled

California, San Diego, Mission Gorge

On May 18, 2024, at about 10:40 a.m., my climbing partner and I prepared to climb Gallwas Crack (5.9) at the Main Wall of Mission Gorge in San Diego. Another friend was with us for his first outdoor climbing session. The three of us had already warmed up.

Access involved scrambling eight feet up to a large, flat ledge, then up and over to another ledge at the base of the route. This ledge was big enough to not worry about falling off, but there was a risk of the belayer getting pulled off if the leader fell before placing any gear. We all wore helmets and were very safety focused.

The ledge was 40 feet above the trail. We built a three-piece gear anchor to secure the belayer (me), and our other friend sat untethered on the large ledge below and left. Gallwas Crack looked challenging, with slippery rock, but my climbing partner had led higher-rated climbs at similar areas, so I thought it would be possible, though perhaps at his limit. There appeared to be plentiful gear placements.

He racked up and we did thorough safety checks. He got up a short fourth-class ramp to a secure stance and put in a No. 0.5 Camalot, clipped with an alpine draw. He climbed to where his feet were level with the first cam and placed another, then climbed to where the second cam was at his waist and placed a third cam.

When the third cam was at his waist, he paused to figure out the move, then yelled, “Take! Take! Take!” I pulled in a couple of arm lengths of slack as fast as I could. The rope started becoming taut just before he fell, but it never became completely tight during the fall. I did not get pulled toward the wall as one would expect. The highest (third) piece pulled immediately, and he continued falling. The second piece also pulled as he rotated backward and began falling headfirst. The first piece caught him. I don’t remember being pulled by the rope despite the fact that he fell 30 feet total, past the ledge, and ended hanging upside down, about 30 feet above the trail.

He was not moving. Our other friend yelled, “He’s bleeding out of his right ear.” I can't recall the sequence, but someone yelled to ask if they should call 911. I asked our other friend to attend, since he had emergency medical training. I slowly lowered my partner as he was pulled over to the large ledge. As I was lowering, his body shook for a few seconds. On the flat ledge, he had a pulse and breathing was heavy. I called 911 at 10:56 a.m. and learned that someone else had already called in.

I clipped my climbing partner into the anchor so I could be freed up to help. I held his head, and he’d periodically sit up and moan, then lie back. We tried to keep him down, and he would tell us to stop touching him. A woman with emergency medical training came over and did a good job helping us all stay calm. She confirmed that my climbing partner could respond to his name, by turning his head. A helicopter arrived, lowering a paramedic with a radio and litter, who assessed his condition. The paramedic tried to place a neck brace, but my climbing partner refused it. When we got the brace on, he immediately took it off. Eventually, he was put on a litter and flown to a trauma center. It was less than an hour after he’d started the climb.

One of the pieces that pulled was a No. 3 (orange) Metolius TCU. The plastic trigger-wire guide on a green (No. 0.75) Camalot was tweaked, so this was probably the other pulled piece. I’m not sure which one pulled first. My climbing partner suffered a severe traumatic brain injury, but he made it through emergency surgery and has mostly recovered.

Video Analysis

Accidents in North American Climbing Editor Pete Takeda and IFMGA/AMGA guide Jason Antin are back at North Table Mountain in Golden, CO to analyze this accident.

They break the accident down into things that could be improved and things that were done really well. Watch the video for a visual analysis.

ANALYSIS

What went right: I was anchored, so I couldn’t get pulled off the ledge when my partner fell. He was wearing a helmet, which probably saved his life. It’s good that we had a third person there, because he was able to respond quickly and help save our friend’s life. We've been able to talk about what happened and support each other. (Source: Anonymous.)

*Editor’s Note: A climber posted on Mountain Project that, in Mission Gorge, “two separate near-fatal accidents” involving cams pulling out occurred in 2024—one on May 18 (Gallwas Crack; described here) and the other on May 19 on the adjacent Nutcracker (5.9+). He also wrote, “Be aware that cams do not hold well on this rock in hot conditions.” Perhaps the Mission Gorge’s slick rock combined with recent rain-generated dirt and silt contributed to the gear pulling. The gear itself may have played a role. Not up for conjecture is that several elements combined to produce an unpredictable accident. The fallen leader was 34 years old and had “many years” of trad experience; the cams did not suffer obvious deformation that would have indicated a high load. As the belayer stated, “They just came right out, with seemingly less than body weight. They didn’t slow the fall at all.”

Support Climbers Recovering From Accidents

The AAC’s Climbing Grief Fund exists to ensure that climbers and their loved ones are met with compassion, care, and community when they are navigating grief, loss, injury, or trauma. It’s one way we look out for one another—long after the ropes are packed away.

When you donate to the Climbing Grief Fund through March 10, your donation is matched—GIVE TODAY!

Donors can recognize someone on our virtual dedication wall by adding a name with—Honoring, In Memory of, or In Gratitude—in the comments field on the donation page.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

Tales from Red Rock's Risk Mistress: Joanne Urioste

Joanne Urioste is a powerhouse in Red Rocks climbing history, and we had her on the podcast to share stories from her recently published memoir, “Collages of Rock & Desire.” Her book is a detailed catalogue of the climbing legacy she shares with her husband George Urioste, including the creation of iconic multi pitch climbs like Epinephrine, Levitation 29, A Dream of Wild Turkeys, and many others. The book is also a detailed account of gear innovations and changing climbing ethics through the ‘70s and 80’s—from swami belts and belay plates, to early adoption of nuts and frontpointing on ice, and adding a run-out bolt here and there to connect discontinuous cracks and make many climbs possible on Red Rocks soaring faces. In the interview, we dive into all of this, plus Joanne and George’s wild love story, managing fear on lead, and climbing as a metaphor for life.

You can find a copy of Joanne Urioste's book on Amazon.

The Prescription—The Stacked Rappel

Rappelling is one of the most accident-prone facets of climbing, with improper/incomplete setup being an all-too-common cause of misadventure. In the 2025 ANAC, we featured an accident that involved a rappel fatality from a difficult ice/mixed route in the Canadian Rockies. Steep, multi-pitch winter climbing combines a challenging environment with the technical complexities of big-wall climbing. Gloved hands, copious gear, and often-cumbersome clothing can impede the usual streamlined rappel setup and safety checks. As John Godino mentioned in his 2025 ANAC Know the Ropes feature, the stacked rappel can help ameliorate these issues by promoting “More efficient rappels with reduced risk—what’s not to like?”

Drama Queen climbs a series of ice flows interspersed with steep mixed sections. In this photo of the Stanley Headwall, the route is roughly left of center. In winter, this 300-meter-tall crag is a crucible for hard ice and mixed climbing; in summer, it’s home to a host of difficult single- and multi-pitch rock climbs. Photo by Parks Canada.

Rappel Fatality | Possible Unsecured Knot

British Columbia, Kootenay Park and Banff National Park, Stanley Headwall

At the end of 2024, a very experienced climber named Dave Peabody (48) fell to his death while rappelling from a route on the Stanley Headwall. Alik Berg was Peabody’s partner on that day. Berg wrote to ANAC:

Dave and I had been regular climbing partners for about 12 years, with many seasons of winter, alpine, and rock climbing. On December 26, we headed to the Stanley Headwall to climb Drama Queen (170m, WI6 M7). This was a fairly routine climbing day for us. That morning, we saw teams on the neighboring climbs French Reality and Dawn of the Dead.

We topped out at dusk (around 5 p.m.) and began rappelling by headlamp. We both used an ATC-Guide on our belay loops and a prusik backup on our leg loops. The last pitch (P4) was the steepest, and we climbed on a single rope (blue) with the second rope (red) as a tag line. The pitch was short enough to be rappelled with the blue rope, while we left red fixed at the beginning of the pitch to pull ourselves back into the anchor atop P3.

This awkward rappel was partly free hanging, and pulling back into the belay required care to not disturb a large, dripping ice dagger. Dave descended first. I soon joined him. He had already begun setting up the next rappel, threading the red rope through the anchor and joining the two ropes with a single flat overhand knot.

The P3 anchor is a pair of modern bolts with Fixe rap rings. There was enough space on the small ice ledge to not be crowded, and we busied ourselves with the routine tasks of rigging the next rappel. I pulled the blue rope, verbally confirming with Dave that the joining knot was in place before making the final tug and pulling up the tail to add a stopper knot. We tied an additional stopper knot in the red rope before tossing it off. We noted a bit of a tangle in the red rope that we’d deal with on the way down.

Dave readied himself to start the rappel. I was distracted with untangling and tossing the remaining rope from the ledge and did not directly observe his connection to the ropes. He started the rappel, moving normally. As Dave descended, my gaze at that moment was on the overhand knot joining the rope ends. I sensed something was off but couldn’t register what it was.

At this point, Dave fell. The interval between sensing something was amiss to when Dave started falling was very short, maybe one to two seconds or fewer. There was enough time to register this thought but not enough to assess, let alone react. I believe he was about five to 10 meters below the anchor when he fell—not when he first stepped off the ledge and weighted the system.

In the immediate aftermath, I became fixated on something being “off” with the knot and that being the likely point of failure. It wasn’t until reaching the ground the next morning that it became clear that the knot was not the cause of the accident.

When Dave fell, I reacted by grabbing the free-running (red) rope and squeezing hard enough to melt my gloves and burn my fingers, but not enough to slow his fall. In the darkness, I could not see him at the base, only the faint glow of his headlamp. It was about 6 p.m.

The team on French Reality had already left the area. The party on Dawn of the Dead had descended, traversed the base of the wall, and were around the corner and out of earshot. About 15 minutes after the accident, their headlamps reappeared as they looped back into view near valley bottom—about one kilometer northwest of my location. I was able to yell down, and they turned around. At 6:45 p.m., they reached the base, and we could communicate properly. It was then that they realized the severity of the situation and activated their inReach.

Dave and I had both carried a cell phone and an inReach. I had my cell phone but my inReach was at the base, while Dave had been carrying his on the climb. The party below had enough cell reception to make calls with Garmin dispatch and Parks Canada.

Parks Canada later reported that I was secure on an anchor and wearing warm clothing. The rescue team decided that given the exposure and technical nature of the location, they would wait until sunrise to mount a rescue.

During the night, I acquired sporadic cell reception, and in the morning was able to send a few texts to the rescue team, who suggested delivering ropes to me so I could descend on my own. This was a great idea, as it eliminated the risk of doing a direct extrication from the steep wall. At 9:20 a.m., a bag containing two ropes and a radio was delivered to me by helicopter long-line. At 9:50 a.m., I was at the base of the route, where I met rescue-team members.

(Sources: Alik Berg and Parks Canada.)

Video Analysis—The Stacked Rappel

One way that rappelling accidents might be avoided is by using the stacked or pre-rigged rappel method. In this video analysis, IFMGA/AMGA guide Jason Antin walks us through the benefits of the stacked rappel.

ANALYSIS

Dave was found with only the blue rope threaded through his device and backup. The device was five to 10 meters from the overhand knot.

The matching, triple-rated 8.7mm ropes showed no signs of damage, and the joining knot and stopper knots were intact. The stopper knots were unfortunately not photographed, so this comes from the rescuers and my own recollections. However, both parties agreed that both stopper knots were present.

It appears that Dave’s accident was caused by an improperly threaded rappel device. The simple solution to that is a basic partner or function check. Alternately, rappelling using the stacked rappel method is a solution. It is common in guiding practice and deserves broader adoption in the climbing community. (See ANAC 2025 KTR, “Crafty Rappel Techniques,” by John Godino.)

Stacked rappel method. Image by AAC Staff Foster Denney.

Though we’ll never know exactly what happened here, these are the scenarios that I’ve come up with:

Device and prusik only loaded on blue rope. During the initial shuffle off the ledge and transition onto steeper ground, both of Dave’s hands were gripping the ropes. Once the ropes were fully weighted, Dave transitioned to a looser grip, perhaps one hand, or maybe he released both hands to deal with the tangled red rope.

Same as above, except the red rope snarled the small ice daggers near the end of P3. They supported his body weight on the initial lower-angle terrain while providing similar tactile feedback to a functioning system. Once Dave was on steeper ground, his full weight caused the ice to fail or pulled the rope tangle through the constriction that had held it in place.

ATC-Guide was properly threaded but prusik backup was attached to the blue rope only. When his hands came off braking, the red rope ran free. The stopper knot was not present, and the rope tail ran through the ATC. (Source: Alik Berg.)

This was a deeply impactful and traumatic event. Writing the above notes and going back to that place in detail has been really hard. But it is important to me that we get this right.

(Source: Alik Berg.)

Got a question about accidents or climbing safety?

Send it to accidents@americanalpineclub.org and hear answers from Accidents in North American Climbing editor, Pete Takeda, and the AAC team on an upcoming March episode of the AAC Podcast.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

The Line—Unclimbed Baffin

Most climbers journeying to Baffin Island in Canada head to the Weasel River Valley in Auyuittuq National Park, home to the world-famous walls of Mt. Asgard and Mt. Thor, among many others. Yet despite more than 50 years of climbing history in this area, there’s still enormous potential just outside the main valley. In April 2025, an ambitious and creative British team explored the glacier systems east of the Weasel River, finding numerous unclimbed peaks and walls.

A striking unclimbed peak to the south of Mt. Bilbo, at the head of the Nerutusôq Glacier. Photo by Tom Harding.

Nerutusôq Glacier and Fork Beard Glacier, Seven First Ascents

Unclimbed walls about 25 kilometers from Kingnait Fjord, which is accessible by boat in summer. The photo is taken from the eastern side of the Fork Beard Glacier, looking approximately southeast. Photo by Tom Harding.

In April 2025, a four-person team made up of Leanne Dyke, James Hoyes, Ben James, and I flew into the settlement of Pangnirtung. Our hope was to use spring snow cover to ski the length of the mountains to the east of the Weasel River Valley, ascending unclimbed peaks along the way. However, on April 7, strong winds and lack of sea ice prevented us from accessing our planned snowmobile drop-off in Kingnait Fjord (the next fjord east of Pangnirtung Fjord). After this false start, we changed plans and were dropped on April 10 just below Summit Lake at the head of the Weasel River Valley.

An aerial view to the east over the Fork Bear Glacier complex, showing the 2025 team’s ascents in this area. Photo by Tom Harding.

We had hoped to ski straight up onto the Nerutusôq Glacier, to the southeast of Summit Lake’s outlet, but a lack of snow meant we spent three exhausting days portaging our sleds, food, and equipment up onto the glacier. We made camp three kilometers southwest of Mt. Bilbo (1,842m).

The team on the summit of Uppijjuaq (1,823m). Photo by Ben James.

From this camp, we made two first ascents. On April 14, we climbed the east slopes to the south ridge of a 1,823-meter peak we named Uppijjuaq. The next day, we made the first ascent of Minas Tirith (1,950m) via its three-kilometer west ridge (PD-), passing tricky steps and steeper granite cracks to an impressive summit tower.

We then skied south onto the Fork Beard Glacier, making two more first ascents, the southwest rib of Aqviq (1,860m) and the west face of Inutuaq (1,637m), as well as a failed attempt on a third peak.

Next, we headed south on the Fork Beard Glacier, hoping to find a pass at the top of the Turnweather Glacier that would connect us to the Gateway Glaciers to the south, but after two days of searching, no feasible route was found. Fortunately, this unnamed valley had never been visited by climbers, to the best of our knowledge, and we went on to make three more first ascents: the south face of Ukaliq (1,532m), west to north ridge of Uvingajuq (1,615m), and the south slopes of Atangiijuq (1,600m).

With so many of the peaks in this area of Baffin given Norse or English names, our team thought it would be nice to instead use the Inuit language to name most of the first ascents. Traditionally, the local population gives names for what the peak looks like or what they see in the local area, and we followed this method. For example, Uppijjuaq means “snowy owl,” Aqviq is “humpback whale,” and Uvingajuq means “diagonal,” after the distinctive ramp we climbed.

The team’s camp on the Fork Beard Glacier, with Inutuaq (1,637m) in the center right of the photo. They made the first ascent by traversing around the right side of the mountain and climbing the west ridge. Photo by Ben James.

To end our trip, we skied four days to exit the mountains: first to the west via the branch of the Fork Beard Glacier flowing south of Tirokwa Peak, then south along the frozen Weasel River, and finally to the sea ice in Pangnirtung Fjord. We returned to Pangnirtung village on April 30, having completed seven likely first ascents and skied around 150 kilometers. The weather was surprisingly stable, with many blue-sky days, and although temperatures at the start of the trip dropped to -30°C, it quickly warmed to a comfortable -10°C.

The eastern portions of the Nerutusoq and Fork Beard glaciers still have potential for future teams. Accessing this area in summer would be a long journey, but using the spring snow opens up the area. [This mostly British team received support from the Mount Everest Foundation; their extensive trip report can be downloaded here. They received additional support from the Arctic Club, British Mountaineering Council, Austrian Alpine Club, and the Alpine Club (U.K).]

—Tom Harding, United Kingdom

Last Call for Canada Reports—AAJ 2026

The 2026 AAJ will publish four more reports from Baffin Island, in addition to the one shared above. We plan to wrap up the Canada section of the book in early February. If you or a friend climbed a long new route anywhere in Canada in 2025, and you aren’t already in contact with an AAJ editor, we’d love to hear about it no later than January 31. Reach us at aaj@americanalpineclub.org.

New Episode—The Direct Line on El Capitan

In November 2025, Sasha DiGiulian free climbed The Direct Line (a.k.a. Platinum Wall), a 39-pitch 5.13d on El Cap, in a 23-day push, including nine days trapped by a storm high on the route. For this episode, host Jim Aikman explores the history and highlights of this relatively new route (first free ascent: 2017), which is becoming known as one of El Cap’s most sustained and high-quality free climbs. Other guests include Elliot Faber, co-developer of The Direct Line and Sasha’s partner for the climb, and Alex Honnold, who also freed the route in November, with Tommy Caldwell.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

Thank You For Making Our Work Possible

Photo by AAC member Jeremiah Watt.

You did it! Thanks to the generosity of our community, the American Alpine Club is starting 2026 on a strong note.

Together, we’re protecting climbing’s future — one gift, one climb, one community at a time.

Looking Back: 2025

The American Alpine Club made a real, measurable impact on the climbing community.

Dispersed $87,000 in climbing and expedition grants, including securing double the funding for our Climbing Grief Fund

Welcomed over 19,900 climbers from around the world to our lodging facilities—all while investing in major upgrades across each location

Advocated for and supported the passage of the EXPLORE Act to prioritize climbing access and outdoor recreation opportunities on America’s public lands

Preserved the culture and knowledge of climbing through our Library and Archives, including supporting over 112 research projects

Reached over 6 million climbers who viewed our new Prescription Videos, and delivered copies of our world-renowned publications, Accidents in North American Climbing and the American Alpine Journal to our members—offering 90 in-depth accident reports and analysis, and 249 inspiring stories from the cutting edge of our sport

Every one of these wins reflects your belief in the power of this community and your commitment to the AAC. Your generosity is what makes the AAC not just an organization—but a movement built by climbers, for climbers.

Looking Forward: 2026

In 2026, the American Alpine Club plans to continue providing these unique benefits to the climbing community, as well as deepening the quality of our resources for climbers. This includes:

Providing our rescue benefit and $5,000 in medical expense coverage to our Partner, Leader, Advocate, and GRF level members.

Continuing to deliver world-renowned publications and media, including the American Alpine Journal, Accidents in North American Climbing, Prescription videos, and the AAC and Cutting Edge podcasts.

Building programming that strengthens members’ connections and creates more opportunities to gather, learn, and celebrate climbing.

Delivering double the amount of Climbing Grief Fund Grants to climbers who need therapeutic support in processing trauma and grief.

Increasing funding for the Research Grant to $9,000 during the AAC 2026 spring grants cycle.

Cultivating community hubs at our six lodging facilities situated near world-class climbing and outdoor recreation destinations.

Expanding our Great Ranges Fellowship events and communications.

Thank you so much for your contribution to the AAC. Your gift enables us to continue delivering critical resources to climbers and fuels the evolution of this shared passion.

We’re excited to continue delivering these invaluable resources and look forward to the next chapter.

Thank you for tying in with us.

Local Hero Dave Hume, on Bringing 5.14 to the Red in the 90s

In the 90s, Dave Hume was one of the Red River Gorge's original kid crushers. After climbing became a family hobby, Dave Hume got obsessed—and left his own mark on the sport.

Dave Hume is now based in Colorado, but loves going back to the Red as often as possible!

In this episode, we talk about what it was like being one of the original Lode Bros, bringing 5.14 to the Red with his ascent of Thanatopsis in 1996, and the one time he beat Chris Sharma in a competition.

He shares the story of how his dad and brother bolted the infamous Breakfast Burrito, one of the Red’s most classic 5.10s, and the sense of discovery of finding new crags like Drive By and Bob Marley.

Plus, we cover the early evolution of the Red from trad to sport climbing, reminisce about Miguel’s before they sold pizza, and how Dave repeated Just Do It, the U.S.’s first 14c, in an insulting few tries. Dive in to hear some fun stories from this Red River Gorge local hero.

If you believe conversations like this matter, a donation to the AAC helps us continue sharing stories, insights, and education for the entire climbing community!

The Line—Desert Towers in Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia is nearly ten times the size of Utah, and most of it is desert. Like Southern Utah, the terrain is riven with sandstone canyons and towers, nearly all of them unclimbed. Last January and February, a German trio did a three-week, 4,600-kilometer loop around the desert kingdom, exploring the traditional-climbing potential. So, how did their expedition turn out? It was a mixed bag.…

Gemini Tower, north of Wadi Al Disah in western Saudi Arabia. After the first ascent of the four-pitch formation, the German team was informed that climbing is not permitted in this area. Photo: Daniel Hahn Collection

Wadi Al Disah, Bajdah, Wadi Dham: 12 First Ascents

Excited and somewhat stressed, we plunged into the crazy traffic of the seven million–strong metropolis of Riyadh in our rental car. Excited because a journey into the unknown lay ahead: a search for climbs in a country that has only been open to Western tourism since mid-2019. And stressed because only five of our six pieces of luggage had arrived.

With a day to kill, Michael “Michi” Bänsch, Daniel Hahn, and I first shopped for supplies, then drove out of the metropolis toward the Edge of the World, a rocky escarpment northwest of Riyadh. The traffic was terrible; one construction site followed another. The entire country is being dug up; money seems endless. Due to the construction work, neither Edge of the World nor the stunning sandstone tower of Faisal’s Finger were accessible. But at least we spent a nice first night in the desert, giving us some relief and preparing us for the coming weeks.

The next day, January 20, our last piece of luggage arrived. We took a deep breath and set off toward Wadi Al Disah, 1,300 kilometers to the northwest, fairly near the Red Sea. Settlements were very sporadic, and the closer we got to the Hejaz Mountains, the more fascinating the landscape became. When we entered Wadi Al Disah, our jaws dropped: endless sandstone cliffs, magnificent scenery, and potential for generations of adventurers. Atir Tower, the valley’s landmark, glowed in the evening light. After finding a place to sleep and cook dinner, we went swimming—yes, swimming! A stream flows through the wadi, providing gloriously green vegetation and offering us a welcome cool-off every evening.

Seppo and Michi starting up the first pitch on Hinterhaus, a 200-meter formation in Wadi Dham. Photo: Daniel Hahn

The next morning, we headed straight to the Atir, a 350-meter tower and one of the few Saudi formations with documented routes. It was climbed by a chimney route on the east side in 2013, by a party including Donald Poe, a U.S. oil engineer and Saudi Arabia resident. In 2020, a group led by Leo Houlding from the U.K. found a new line on the west face and named it Astro Arabia (5.11). We climbed the original route (UIAA V or about 5.7), hoping to encounter rock roughly akin to the well-known Wadi Rum in Jordan, about 230 kilometers to the north. In fact, the rock turned out to be quite brittle and dirty. But what a summit!

Over the next few days, we searched for more climbable rock, which was harder than expected: There are endless formations, but upon closer inspection, many turned out to be too difficult, too fragile, or both. The fact that we did not have a drill or bolts didn’t make it any easier. But we soon made the first ascent of a beautiful tower (which had obviously been climbed by locals up to its forepeak), right at the valley entrance. We called it Burg (“Castle”) and the route Uralter Weg (“Ancient Path,” 80m, VI/5.10-).

Further into the valley, another peak tempted us, perhaps 100 meters high and with what appeared to be a climbable route. Soon after we started climbing, however, we heard strange noises from below. The SFES (Special Forces Environmental Safety) rangers had spotted us and were ordering us back down. After a lengthy but quite friendly discussion, we were surprised to learn that climbing is prohibited in the entire Wadi Al Disah.

We detoured to a nearby canyon just to the north, Wadi Tarban (or Tourpan), where we climbed Gemini Tower (130m, 4 pitches, V+) and Porcelain Tower (scrambling plus 25m, VI), before being informed by friendly locals that climbing was not allowed there either. So, we left the Wadi Al Disah area earlier than planned and continued to Bajdah, a small town farther north, near the city of Tabuk, where we had been told climbing is officially permitted.

Michi in Al Gharameel Nature Reserve, where the climbers ascended five needles up to 20 meters high. Photo: Daniel Hahn

Here, a completely different landscape awaited us: an open plain from which countless rocks rise, some enormous massifs, some picturesque needles. It may be hard to imagine, but deciding where to start in a sea of rock is truly challenging. But we soon found some nice objectives, including a two-pitch needle that we named Stoneman, climbed by a new route called Triumph des Willens (“Willpower,” ca 100m, VII-/5.10). We also reached all five summits of a formation we named Felsenbrüder (“Brothers of Stone”), about 150 meters high, by the route Geschenk der Wüste (“Gift of the Desert,” VII-). The climbing here was challenging, with brittle overhangs that had to be overcome or bypassed, followed by easy scrambles to the summits.

Next, we visited the nearby Wadi Dham (Damh), where we fanned out, eyes upward, looking for opportunities. We chose a pagoda-like formation we called Hinterhaus. Although generally easy, it also had many small overhangs, and one even required aid: Weg des Willens (VI+ C1). Two more days here brought us the first ascent of another small tower and some beautiful hikes in an impressive landscape—simply a wonderful time.

On all of our climbs, we only used cams, nuts, and slings. No bolts were placed. We live in Dresden, near the famed sandstone towers of Elbsandsteingebirge and Adršpach (Czechia), and we are very experienced sandstone climbers. Yet, even though Saudi Arabia seems to offer endless sandstone climbing, the rock is very unpredictable, even when it looks great—sometimes a hold stays put when weighted, sometimes it pops off. With all the dust and coarse sand, the ropes got stiffer every day—all of our gear suffered as much as our nerves.

After two weeks I headed home, while Michi and Daniel stayed for another week. During this time, they visited Al Gharameel Nature Reserve and found countless sandstone needles. They climbed five towers, up to about 20 meters high and UIAA VI (5.9+/5.10-), without seeing a single trace of previous climbers.

During our travels, we met incredibly friendly people, some of whom offered us water or invited us to share tea or coffee, and shared interesting conversations, sometimes in perfect English, sometimes with gestures and Google Translate. We enjoyed a simple life, sleeping out on the sand. On some mornings, our sleeping bags sparkled with frost. We pushed or dug the car out of the sand twice. In all, we summited 13 formations, probably 12 of them first ascents.

—Stephan “Seppo” Gerber, Germany

Sport Climbing in Saudi Arabia

In addition to the desert towers explored by this team in 2025 and the British group in 2020, a bit of early traditional climbing was reported on granite in the western part of Saudi Arabia, south of Ranyah (AAJ 1989). Of more interest to many climbers will be the sport routes developed in late 2018 at various sandstone, granite, and limestone crags—some of them quite impressive—by Read Macadam (Oman) and various European climbers, who worked with the Saudi Climbing and Hiking Federation. The federation has published PDF guides to these crags, and many of these routes have been posted at Mountain Project.

Overview of the impressive Olympic Crag, which has about 40 routes on steep granite, two and a half hours east of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Astro Arabia

In early 2020, shortly after Saudi Arabia opened to tourism, British climbers Waldo Etherington and Leo Houlding visited Wadi Al Disah and climbed two large towers, leading to a film, Great Sheiks, as part of the Brit Rock series. Here’s the opening segment from the film, covering the first ascent of the 100-meter Leaning Tower of Disah—it gives a good sense of the “acquired taste” for exploring variable Saudi sandstone.

The Cutting Edge Podcast: Cerro Torre Solo in Winter

On September 7, Colin Haley reached the summit of Cerro Torre all alone—a climb that tested this Patagonia veteran perhaps more than any before. It was the first winter solo of the stunning granite needle, and the culmination of a nearly 20-year dream. Don’t miss this extraordinary episode of the Cutting Edge.

The Line is Powered By:

The Line is Supported By:

Sign Up for AAC Emails

Know Before You Go—Calling for a Rescue

Originally published in Guidebook XVI

If you’re an AAC member at the Partner, Leader, Advocate, or Great Ranges Fellowship level, then you have access to the AAC’s rescue benefit. Make sure you know how to initiate a rescue—before you find yourself in that kind of situation.

Pre-Program Your Garmin inReach

We know that a lot of our members put their trust into Garmin products* as a backup for when a cell phone isn’t reliable. Here’s how to prepare your Garmin device to contact Redpoint Travel Protection in the case of an emergency away from home:

Add Redpoint’s operations team as one of your emergency contacts with the email operations@redpointtravelprotection.com.

Save your preset messages for emergency and nonemergency scenarios.

Send a test message to Redpoint to confirm that you’ve successfully set them up in your device.

Go to americanalpineclub.org /rescue to learn more about your rescue and medical benefit and find further details about how best to set up your Garmin device.

Other Ways to Prepare

Make sure your climbing/adventure partners also have AAC memberships! If not, make sure they know that you are covered in the event of a medical emergency and how best to contact Redpoint on your behalf if you are incapacitated.

Inform your family and loved ones that if the worst thing happens, you are covered for $15,000 in mortal remains transport through Redpoint.

If you’re working with a guide company, inform them of your preference for using Redpoint Travel Protection in the event of a medical emergency.

*Did you know that AAC members receive 20% off Garmin products through ExpertVoice? Sign up for your account today at expertvoice.com/group/aac to start shopping with hundreds of brands.

The Prescription—Crevasse Fall

This month, we feature an accident that occurred in 2025 on Mt. Baker’s Squak Glacier, on the peak’s southern facet. On May 23, Daton Nestlebush fell into a crevasse while on a snowboard descent. His partner Manny Pacheco, travelling on skis, effected a rapid rescue. Pacheco captured a rare POV video of this successful 1:1 partner crevasse rescue and later posted it on Instagram (@pmannyy). Below, we feature this remarkable video, along with a blow-by-blow analysis by IFMGA guide Jason Antin.

Mt. Baker’s Squak Glacier is the glacier/snowfield on the left-center of the peak. This classic ski-mountaineering route, known for its excellent corn skiing, is one of Baker’s most popular ski descents. It requires extensive glacier travel and offers thousands of feet of descent. Photo by AAC member and grant recipient Craig Muderlak.

Crevasse Rescue | Fall Into Crevasse

Mt. Baker, Squak Glacier

On May 23 at 3 a.m., my longtime friend Daton Nestlebush (26) and I, Manny Pacheco (27), set out to ski Mt. Baker via the Squak Glacier route. I’m experienced in ski mountaineering and crevasse rescue, and I hold an AIARE 1 avalanche-training certification. Daton had limited experience in high-alpine terrain—this was his first time on a glacier attempting to summit a Cascade volcano.

Earlier, our team had thinned from four members down to two. I took the risk of glacier travel with an inexperienced partner because of my familiarity with the route. We reached the toe of the Squak Glacier at 5:15 a.m. and put on harnesses. I taught Daton how to bury a picket and fix a rope to it—the minimum self-rescue skill one needs if one falls into a crevasse and is still conscious.

We reached the top by noon (my seventh Mt. Baker summit). We then transitioned into descent mode and made our way down to the Squak Glacier, skiing 500-foot pitches while taking turns watching each other. At 1:15 p.m., at 7,950 feet, I stopped abruptly when I saw large crevasses 100 feet ahead. I radioed Daton, still above me, to traverse to skier’s right and keep a high line. He passed, and we both started a 300-foot descending traverse to bypass hazardous convex terrain.

As I followed, Daton collapsed a thin snow bridge and dropped into a crevasse. He raised his arms into a “T” shape, catching himself between the uphill and downhill crevasse lips. His snowboard tip caught an ice chunk four feet below the surface. Only his arms and head were visible.

My most pressing goal was to anchor Daton. I immediately redirected uphill and crossed another small crevasse. I stationed myself 20 feet uphill, using my pole to probe. I told Daton not to move and that I’d throw him a rope in 60 seconds. “You’re going to be okay,” I reassured him.

He was holding himself strenuously by his arms above the crevasse, which we later estimated to be 60 feet deep. He said, “Can you make that 45 seconds?”

Fortunately, the late-spring snow was perfect, and I made a trench and buried a picket in a deadman position, stomped it one foot deep, and backfilled the trench. I clipped the picket and tied another figure eight on a bight 20 feet from the anchor and threw it to Daton. My split-second decision to use the eight was based on urgency. Daton was able to grab the large loop—he later said this was critical to his survival.

I knew the clock was ticking but stayed methodical. Daton grabbed the figure-eight loop with his right hand. As he let go of the uphill lip to clip, he dropped a couple feet, fully weighting the system. At the same time, I attached myself to the rope as a secondary anchor. This all felt like ten minutes but, in reality, it was probably more like 30 seconds.

Daton Nestlebush emerging from the crevasse. Minutes prior, Nestlebush’s head was five feet below the surface after he fell ten to twelve feet into the deep pit. Photo by Manny Pacheco.

I wanted Daton to pull himself over the lip, but after his head dropped below the surface, this was no longer possible. I began setting up a haul system by burying my ice axe in a deadman, connecting it to the picket, and creating a master point. I took myself out of the system and reconnected with an extended prusik. The weight transfer lowered Daton another few inches; his head was now five feet under the surface.

Although this stage was less time-sensitive, I was still concerned about “Harness Hang Syndrome”—suspension trauma in which the victim loses consciousness due to lack of blood circulation. I began to rig a 3:1 haul system. I threw a rope end down to Daton, and he clipped it onto his belay loop. Although I was unable to “prepare the lip” with a pole/axe underneath the loaded rope due to the probability of a secondary crevasse, I figured we could problem-solve for this once his head was above the surface. I placed a Micro Traxion on the master point and a prusik on the load line. I clipped the redirected load line onto my belay loop and told Daton to expect to be raised. After double-checking the system, I bear-crawled uphill until the prusik had to be reset. A 3:1 system with friction meant I was pulling 100 to 120 pounds. I repeated the sequence of bear crawling, resetting the prusik, and repeating.

Daton’s face was now above the surface, but progress halted as the haul rope cut into the lip. I threw him the original end of the rope to clip onto his pack. I also told him to unbuckle one of his snowboard boots and use the original fixed rope as a handline. Being able to use his feet, eliminating the pack weight, and having a handline allowed Daton to escape the crevasse.

VIDEO ANALYSIS

Manny Pacheco’s video gives us a firsthand look at a real-time crevasse rescue. In this month’s Prescription video, IFMGA/AMGA Guide Jason Antin reacts to the footage and walks through the rescue step-by-step, highlighting what went well and offering recommendations for similar situations.

ANALYSIS

Regardless of how “chill” or (seemingly) filled, an unlucky pressure point on a glacier can lead to a nightmare scenario. The snow bridge was intact; the hidden crevasse was exposed only after the bridge failed.

Fortunately, Daton was in front and I had a visual. Had he fallen into the crevasse behind me, I might not have immediately noticed. This would have dramatically delayed any rescue.

It was lucky that the less experienced person was the one who fell. Had I fallen and become unconscious, we’d likely have needed the help of other skiers nearby. It was also good that Daton caught his fall at the lip—preventing a 60-foot fall—and was able to hold on for the two minutes it took to fix the line. Had Daton been alone with no witnesses, he likely would have fallen below the surface. Snow/ice dampens any yelling.

The process and system I used were not flawless, but I had to act decisively. In practice scenarios, you have time to prep, but in reality, things happen fast. The key is to stay methodical; slow is smooth, smooth is fast.

I should have stopped Daton before he passed me, as he is much less experienced in this terrain. Had he followed me in a higher traverse line, he likely would have avoided the crevasse fall. Also, if I had looked at our position before reaching the convexity, we could have bypassed the crevasse earlier. I was too caught up having fun and skiing.

I’m now much more cognizant of communicating with my partners during glacier travel, as well as of their experience level. This report should encourage glacier recreators to acquire competence to handle worst-case scenarios. Please take crevasse-rescue courses from professionals and/or partner with knowledgeable friends and mentors. Had I not learned and annually refreshed these skills, the outcome would have been much different.

(Source: Manny Pacheco.)

The Prescription is Supported By:

Sign Up for AAC Emails

Explore Prescription Stories

A Tribute to Chuck Fleischman

PC: AAC member Jeremiah Watt

We are sad to share that beloved AAC community member Charles (Chuck) Fleischman passed away in November of 2025. Chuck was a devoted member of the AAC board of directors from 2013 to 2019, and was truly a person who lived out loud.

Chuck was a Harvard graduate who cofounded Digene Corporation, a molecular diagnostics company. Chuck’s work with Digene, as President, CFO, and director, resulted in the first FDA-approved test to detect high-risk HPV before it caused cervical cancer.

Photo provided by Chuck Fleischman during his BOD tenure

When he semi-retired, he threw himself into supporting other meaningful work, including his board term at the AAC. With Jackson Hole as their home, Chuck and his wife Lisa wanted to make a difference in their community. So their first step, beyond membership, was giving back to the local AAC community by supporting the introduction of solar panels on Cabin 2 at the AAC’s Grand Teton Climbers’ Ranch.

As an AAC board member, Chuck was the kind to always be outspoken and always push for greatness. He was very mission driven, always pursued excellence, and held the AAC to those same standards. Phil Powers, past AAC Executive Director, remembers his tough questions, but offered always with an upbeat demeanor, as well as a gregarious laugh.

Chuck’s commitment to the AAC was grounded in his love of the mountains and wilderness. He would ski as many days as the weather gods would allow, including more than 80 days each season, even as he was fighting off cancer. He regularly went on big ski adventures with partners like Jimmy Chin and Kit DeLauriers. Chuck was also a river rat and a committed climber, having summited El Cap, gone on expedition to K2, and floated the Grand Canyon many times.

Chuck lived larger than life, and his impact on the AAC will be felt for years to come. Our thoughts are with Chuck’s family as they process his passing.

Memories From AAC Community Members:

“Chuck has been a career mentor, as well as a climbing and adventure mentor for me. He taught me how to be an effective business professional and how to take my experience on the board of the Bay Area Climbers Coalition and carry it into my role as an AAC board member. He also taught me how to look for big objectives in the mountains. Serving on the AAC board was probably the biggest summit I could have aimed for, and he inspired me to pursue fourteeners like Shasta, Whitney, and other big goals. All of it was a direct result of his mentorship.”

—Jen Bruursema, former AAC board member

“If I was going on a hike with Chuck, I knew it was going to be A) a great day, and B) there were going to be some hard questions to tackle along the way. I knew it meant he really just cared about the Club. He wasn’t going to let a day go by without pushing us forward.”

—Phil Powers, former Executive Director of the American Alpine Club

Foremothers: The Story Behind the Four Women Who Helped Found the American Alpine Club

By Sierra McGivney, research supported by the AAC Library

Originally Published in Guidebook XVI

Fuller, Miss Fay

Peary, Mrs. Robert E.

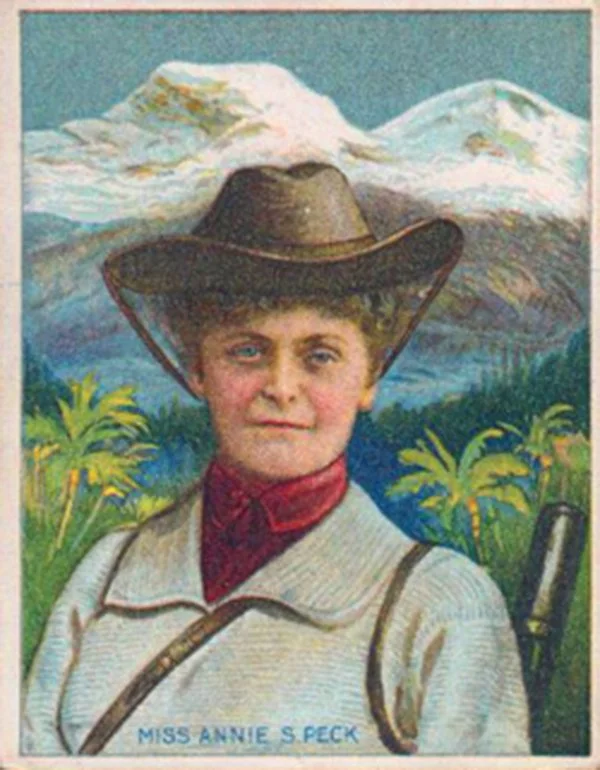

Peck, Miss Annie S.A.M.

Workman, Mrs. Fanny Bullock, F.R.S.G.S.

Their names were written in ink, part of the list of founding members of the American Alpine Club in the AAC bylaws and register book. These four women answered Angelo Heliprins' call to establish an “Alpine Society.” The American Alpine Club was established in 1902, but would not get its name until 1905.

The founding members determined that dues were to be five dollars a year, about $186.90 in today's money. This early version of the Club was interested in projecting a reputation of mountain expertise: members had to apply for membership with a resume of mountain climbing or an explorational expedition they had participated in. Those without a sufficiently impressive resume would not be accepted as members. All the founders had lists of their ascents and exploratory expeditions underneath their names to drive the point home that this was a club of high mountain achievers.

It was no small feat that these women were invited to participate in founding an alpine club at the turn of the 20th century. After all, women weren’t allowed in the British Alpine Club until 1974, forcing women to create their own alpine or climbing clubs.

But Fay Fuller, Josephine Peary, Annie Peck, and Fanny Bullock Workman were forces to be reckoned with, each in their own way. They helped steer the American Alpine Club from its beginnings and pushed boundaries in mountain climbing and Arctic exploration, all well before the 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, gave women the right to vote. Each year, their new accomplishments were published in the bylaws and register book under their name, and some were even invited to speak during the AAC Annual Gathering about their expeditions.

Ultimately, these four women are foremothers to American climbing and exploration. Their stories are shaped by their historical context, but the meaning of their mountain achievements is timeless.

Miss Edwina Fay Fuller was the first woman to summit Mt. Rainier in 1890. Fuller also climbed other glaciated peaks in the Cascades: Mt. Hood, Mt. Adams, Mt. Pitt (now Mt. McLoughlin, which still had a glacier until the early 20th century), and Sahale Mountain. She was described as self-reliant and dogged.

Fay Fuller’s ascent of Rainier nearly ostracized her from Tacoma society—not because she was mountaineering but because of what she wore and who she traveled with.

Her party of five, all men except for her—scandalous for the time—woke up on August 10, 1890, at half past four and began their arduous journey toward the summit. In a 1950 feature article about Fuller in Tacoma’s newspaper, The News Tribune, she said, “I was very nearly ostracized in Tacoma because of that trip—a lone woman and four men climbing a mountain, and in that immodest costume.”

Her “immodest costume,” an ankle-length bloomer suit covered with a long coatdress, was made of thick blue flannel. She also covered her face in charcoal and cream to prevent a sunburn (unfortunately, it didn’t work). Fuller was determined to reach the summit on this attempt, her second up Mt. Tahoma or Tacoma, now Mt. Rainier.

Fuller and her group climbed the Gibraltar Ledges, a Grade II Alpine Ice 1/2 with moderate snow climbing and significant rockfall hazard. Today, the most popular route on Rainier is Disappointment Cleaver, a mix of snowfields, steep switchbacks, and crevassed glaciers, but no technical climbing. Fuller and her team navigated the difficult and exposed terrain of there route with little prior experience and with gear we wouldn’t dare use today, successfully summiting Rainier.

Len Longmire, their guide—though he had never been to the summit—recalled that one of the group members offered Fuller a hand at an especially dangerous place. “No thanks,” she replied, “I want to get up there under my own power or not at all.”

That night, under the stars, the team slept in one of many craters on the stratovolcano, listening to avalanches raging down the mountain. The team continued down safely the next morning, leaving a sardine can containing their names, a tin cup, and a flask filled with brandy as proof of their adventure.

Fuller went on to summit the mountain once more with the Mazamas in 1894.

Her ascent led to her becoming a fierce journalist. She went on to cover the Chicago and St. Louis world’s fairs, and helped found the Mazamas in 1894, the American Alpine Club in 1902, and The Mountaineers in 1906. She became the world’s first harbor mistress in Tacoma and was an actress. Expectations be damned.

Mrs. Josephine Peary attended Spencerian Business College and graduated as the class valedictorian in 1880. Fueled by her own sense of adventure, she accompanied her husband on four of his Arctic expeditions, learning how to hunt, fighting off walruses, and exploring the breathtaking beauty of Greenland. She was considered the “First Lady of the Arctic” and gave birth to her first child, Marie, about 13 degrees, or just under 900 miles, from the North Pole in 1893.

“I cannot but admire her courage. She has been where no white woman has ever been, and where many a man hesitates to go,” wrote her husband, Robert Peary—who was embroiled in his own controversy in the early 1900s about whether he “discovered” the North Pole and his treatment of the Greenlandic Inuit—in the preface of Josephine’s book My Arctic Journal.

When the American Alpine Club was formed, sport and trad climbing didn’t exist, and ice climbing was extremely primitive. Exploration was nearly as important as mountaineering in defining the sport.

The American Alpine Club’s foundation was based on exploration and mountain climbing. Indeed, included in the 1902 bylaws was the following mission: “The objects of the Club shall be the scientific exploration and study of the higher mountain elevations and of the regions lying within or about the Arctic and Antarctic Circles; the cultivation of the mountain craft...”

Josephine Peary was not a climber. Her expertise was Arctic exploration, which was wholly unknown to the Western world at the time. In 1891, Peary ventured to northern Greenland with her husband and their crew on the Kite. She spent days under the midnight sun gathering yellow arctic poppies and shooting auks, gulls, and eider ducks.

On September 23, Mrs. Peary joined a small group on a smaller boat, the Mary Peary, to head up Inglefield Gulf. They searched for walruses to obtain the ivory in their tusks and meat for the coming winter. At this time, ivory was in high demand, with the United States taking in 200 tons per year by 1913. The devastating effects of the ivory trade on animal populations have made it illegal since 1989.

Robert Peary had brought a Kodak camera and asked the crew members to row until he said stop. He was so engrossed in getting his picture just right—much like a national park tourist—that he forgot to tell them to stop and ran right on top of an ice cake, nearly tipping the boat over. In the chaos, a walrus was harpooned and it dove underneath the water, dragging the boat off the ice cake and righting it.

But the damage was already done. According to Peary, 250 walruses surrounded the boat and bullets started flying. The walruses were not going down without a fight. Bullets whistled by Josephine’s ears in all directions while she reloaded guns.

“I thought it about an even chance whether I would be shot or drowned,” wrote Peary in My Arctic Journal.

This was just the beginning of their time in the Arctic, and danger was all around them, but she was excited by the uncertainty.

Support the Library

The Henry S. Hall Jr. American Alpine Club Library houses one of the world’s finest collections of mountain-related artifacts, archives, rare books, maps, and media. A climbing bibliophile’s dream, the library contains more than 60,000 books and all the information you could ever want on mountain history, mountain culture, climbing routes, and more.

Donate to the AAC Library to support climbing archives and research!

Today, Annie Peck might be best known for wearing knickerbockers on her 1895 ascent of the Matterhorn. According to Peck’s article “A Woman’s Ascent of the Matterhorn” for McClure's Magazine, wearing knickerbockers with or without a short skirt was the norm when “high climbing.”

Annie Peck. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

But not everyone felt this way. Both in and outside the context of mountain climbing, women could face retribution, such as arrest or fines, for wearing pants, but most of the time, they just walked away with damaged reputations or faced social exclusion for their fashion choices. However, some women were arrested for wearing pants and even jailed. Emma Snodgrass, in 1852, was arrested several times for wearing pants in Boston, and Helen Hulick spent five days in jail in 1938 for wearing slacks to a court hearing in Los Angeles.

Peck was a suffragette—whether her pants-wearing was an act of political defiance or a matter of safety, other women had been badly injured or perished while wearing skirts climbing, and she would not be one of them.

“For a woman in difficult mountaineering to waste her strength and endanger her life with a skirt is foolish in the extreme,” wrote Peck in a 1901 article for Outing Magazine titled “Practical Mountain Climbing.”

Peck was a former Latin professor at Smith College who left it all behind to climb mountains and lecture about her adventures. From 1890 to 1910, she climbed a dozen mountains in Europe and Latin America. She would lecture, save up her money, climb mountains, and then repeat the process.

Peck was on the hunt to stand on the apex of America and thought she had found it in Mt. Huascarán in Peru. In 1908, at the age of 58, she successfully summited the mountain on her sixth attempt. She was the first known person to ever stand on top of Mt. Huascarán.

With the help of fellow American Alpine Club member Herschel Parker, a physicist and mountaineer, she determined that the top of the mountain was around 23,520 feet, but she took no measurements from the summit, only the saddle. Peck’s ascent and the associated height she had achieved meant she now held an altitude record, eclipsing Fanny Bullock Workman’s previous record. The claim would start one of the biggest disputes of mountaineering history.

Fanny Bullock. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

Fanny Bullock Workman was a fierce woman you wouldn’t want to cross. She had an impressive climbing resume, with ascents in the Alps, the Karakoram, and the Punjab Himalaya— she had one of the longer lists of ascents in the AAC’s founders section.

Deeply ambitious, Workman snatched the women’s altitude record from Annie Peck in 1906 when she climbed Pinnacle Peak in the Nun Kun massif in the Himalaya. This spurred Peck to try to take the record back with her climb of Mt. Huascarán, which she claimed to be higher than Pinnacle Peak.

People were engrossed in their feud. The media couldn’t get enough of two powerful women in the same field fighting for the top spot—or rather, the highest spot. Both women gave interviews for articles in newspapers like the Trenton Evening Times, Harrisburg Daily Independent, Detroit Free Press, and Suburbanite Economist, to name a few—defaming one another and trying to frame the story's narrative for their benefit. Whether their feud was malicious or mutually beneficial, people knew their names and accomplishments as mountaineers first, then as women.

In 1909, the American Alpine Club invited Annie Peck to speak about her ascent of Mt. Huascarán. However, the Club grew concerned when newspaper coverage and fans began to question how she ascertained the height of the mountain. Earlier on the same day of her lecture at the AAC’s annual meeting, Charles E. Fay, Vice President of the AAC, proposed an investigation into the height of Huascarán since “exaggerated reports have recently been circulated by the press...regarding the altitude of Mt. Huascarán.”

News outlets exaggerated the peak’s height to up to 26,000 feet. Peck had not brought an aneroid barometer—a sealed metal chamber that expands and contracts depending on the atmospheric pressure around it—with her on the climb to measure the altitude, nor did she take a measurement from the summit, so she couldn’t be sure about the height.

Workman wanted to end speculation and get her title back. In 1909, she spent the equivalent of half a million dollars to send surveyors to Peru to find the true height of Mt. Huascarán. The surveyors returned with triangulated heights for both the north and south peaks. They determined that the north peak was 21,812 feet (modern technology has determined it is actually 21,831 feet) and the South Peak was 22,187 feet (actually 22,205 feet). Either way, Pinnacle Peak was higher than both.

According to a 1911 New York Times article, the Academy of Sciences ruled in Workman’s favor. The year prior, in a letter sent from Henry G. Bryant, then AAC President, to Annie Peck, Bryant said the AAC sided with Workman’s assessment of the peak’s height. Workman had won back the altitude record, retaining her reign over women’s alpinism.

Caught off guard, Peck didn’t hesitate to make a quippy remark in a letter back to Bryant: “I had not been aware that her interest in my ascent of Huascarán extended so far, though I am not surprised. What fine thing it is to have plenty of money!”

But not all was lost for Peck. In 1910, the Hassan Cigarette Company featured a series of trading cards titled “World’s Greatest Explorers.” Out of 25 cards, Peck was the only woman featured. That same year, the Singer Sewing Machine Company gave away a packet of postcards featuring Peck’s travels and climbing accomplishments with every machine they sold. She still published her book about her expedition on Mt. Huascarán, but switched the title from The Apex of America to A Search for the Apex of America. She was a household name, something money can’t buy.

Still, you wouldn’t have wanted to be seated between Peck and Workman at the American Alpine Club Annual Gathering that year.

These four women helped shape the Club as we know it today. Fuller, Workman, Peck, and Peary were strong-willed, educated women in a world governed by rules and regulations of what a woman should be. Each woman stood defiant in her own way. Fuller was independent. Peary welcomed exploration. Peck believed in safety regardless of norms. Workman was dogged in all of her pursuits. They were courageous and ambitious, petty and imperfect. They were history makers. They were part of something bigger than themselves.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

Setting the Climbing Record Straight, with Gunks Legend Russ Clune

Russ Clune is a climbing lifer. He came up climbing at the Gunks, traveled around the world to climb with friends and legends like Wolfgang Gullich, and would help establish the iconic Gunks 5.13 Vandals, alongside Jeff Gruenberg, Lynn Hill, and Hugh Herr. He also shares about sending Mantronix, his hardest climb ever, “back when 5.14 was hard.” These days, he’s a keeper of stories from the Gunks and across the world, and has a running record of Gunks climbing history in his head. On this episode, we meander through stories from Russ’s many climbing travels, explore Gunks toproping ethics and the often forgotten tactic of yo-yo climbing, and set the record straight on some of the most iconic cutting edge Gunks ascents from the 70s and 80s.

If you believe conversations like this matter, a donation to the AAC helps us continue sharing stories, insights, and education for the entire climbing community. Donate today!

Guidebook XVI—AAC Updates

The Lizard Life: A Glimpse at Hueco Climbing Culture in Its Modern Age

By Hannah Provost

Originally published in Guidebook XVI

Luis Contreras is breathing steadily, forcefully, with intention.

He is 15 feet off the deck, and has 20 more feet of textured edges, sidepulls, and huecos to top out Wyoming Cowgirls, a 35-foot V5 on Hueco Tanks’ North Mountain that has recently been reopened.

A few pads sit lonely in the rocks below. Each of his precise foot placements and composed breaths are indicators of the stakes, and they reflect the time this climber put into top-rope rehearsing such a consequential highball. His movements are linked in chains of powerful bursts punctuated by rests. A certain barely observable shaking reverberates from his core into his limbs, but his breaths and the wind are the song he is dancing to—the shaking and the fear squashed down.

For Contreras, “the best climbs are the ones that even if you’re not a climber you walk by and you say, 'Wow that’s a sick climb...' I [am] drawn to these striking tall faces.” Wyoming Cowgirls had always been one of those climbs.

Contreras tops out quietly, his focus unwavering until he is fully over the rounded slab of this immense boulder, where he sits. No whoops, no cheers. Just a private adrenaline high coursing through his veins.

Instead of celebration, he gazes out to the brush-filled desert beyond.

How do you understand the essence of a place? There are of course the facts and figures, the ecology and topography of the terrain, but there are also the traditions and rituals and history of the people who move across it. Such entanglements are why some might say that “the climbing community” (singular) is a misnomer. Our landscapes too-specifically shape us.

For example, Rifle is the land of lifers. That tight canyon, with its near-instant access to climbing seconds from the car, allows for kids splashing in the stream, craggers at Project Wall rubbernecking as you drive by, and the daily parking shuffle as you move from crag to crag. Ten Sleep is Adult Summer Camp: Given the long journey required to get there and its minimal infrastructure, the place welcomes tech bros and remote workers to set up shop for a month or the whole summer, with scheduled camp activities limited to river time, brewery time, or climbing time. As a final example, the Red River Gorge is never never land, where a dirtbag might never grow up.

Climbing cultures, like any culture, are a mixture of language, beliefs, rituals, norms, legends, and ethics that are largely shared by a community and emerge from the interaction of that community with their landscape. Hueco’s iconic roofs, abundant kneebars, airy highballs, deep bouldering history, importance to Indigenous cultures like the Tigua Indians of Ysleta del Sur, and fragile and rare ecosystem shape its climbers too, on an individual level and at scale.

Bouldering in Hueco is an intimate affair. With guides required to access most of the climbing, and groups capped at ten people, “most people know most people, and if you don’t know them it’s only a matter of time,” says Luis Contreras, who is a Hueco guide of a decade and El Paso born and raised.

Most climbers at Hueco fall into one of four groups: the El Paso “city” climbers, the lifers who own property right outside Hueco Tanks State Park, the seasonal dirtbags who migrate every winter, and the out-of-town visitors who pilgrimage there (often yearly) when they can scrabble together some PTO. Even the visitors become known entities—once you have a guide you trust, why not come back to climb with them again and again? You’ll likely find who you’re looking for at one of three community hubs: the Iron Gnome, the AAC’s Hueco Rock Ranch, or the Mountain Hut.

Photo by AAC member Dawn Kish.

Within such a small community, a run-in with an old head or unique character is considered commonplace. You might chat with Lynn Hill over beers at the Iron Gnome, or spot Jason Kehl out in the distance developing a new line. You’ll likely wave at Sid Roberts as he leaves the park from his early-morning session, or even share a laugh with the colorful John Sherman—the originator of the V-Scale.

But no matter what kind of Hueco climber you are, climbing at Hueco feels deeply entangled—it requires a self-consciousness of landscape, access, and ethics that doesn’t just fall away when you throw down your pads and pull onto rock. But that’s not a downside for locals like Luis Contreras and Joey McDaniel. That’s the richness of it.

Among the javelinas and ringtails, among the scooped huecos and textured patina crimps, it’s common to hear the idea that “climbing in Hueco is a privilege.”

Again and again, locals point to a shared ethic when asked about the culture of Hueco. There is a protectiveness over the ecological uniqueness of the place. The Chihuahuan Desert holds 25 percent of the world’s cacti diversity after all—including prickly friends like the Texas rainbow cactus, scarlet hedgehog cactus, and horse crippler cactus. Hueco guide Joey McDaniel always likes to say, when it comes to Hueco, “the more you look, the more you see.” And indeed, for the ancient water systems in the huecos for which the park gets its name—where the famous fairy shrimp eggs lie in wait, for years at a time, anticipating the water that will enable them to hatch— this is most certainly the case.

Some Hueco climbers express pride in the sandbagged nature of the grading. Others hold tight to the humbling challenge posed by the proliferation of highballs in the area.

Others note the awe of walking past ancient rock art on your way to the proj, or learning from a tribal elder during the park’s Community Fair (also known as the Interpreter Fair) about the way local tribes continue to celebrate Hueco as a sacred space.

For some, there is something special about how knowledge and local ethics are passed down orally—from guide to climber as they laze about in the shade between burns. Whether it’s the story behind the FA of Scarface and The Flame, or how Verm started it all.

Plus, climbing at Hueco doesn’t come easy. It’s serious business that you follow established trails, and climbing is an absolute no-go until at least 24 hours after it rains. Water scarcity in this desert area can be a pain for van-lifers, and group dynamics among tours can be a challenge when climbers don’t agree on an itinerary, or are restricted by the number of groups that can be in one area at a time. Evidently, going with the flow is essential.

Photo by AAC member Michael Lim.

Photo by AAC staff Foster Denney.

Book Your Stay at the Hueco Rock Ranch

The AAC’s lodging facilities are a launch pad for adventure and a hub for community and the Hueco bouldering season is upon us! Experience this place for yourself by booking your stay at the Huceo Rock Ranch today.

AAC members enjoy discounts at lodging facilities across the country. Not a member? Join today.

But these are the rules of the Hueco game.

Some of Hueco’s traditions flirt with a classic climbing motivator: competition.

Photo by AAC member Foster Denney.

Challenges are what you get when locals get bored—or when climbers want to break from the bleariness of project-send-repeat. They range from famous and lauded, like the Big Five in Fontainebleau—a circuit of five classic problems from 7c to 8a (V9 to V11) in the Cuvier Rempart sector, which pro climbers now complete in a day—to locally legendary, like the Dungeon Master challenge at Staunton Rocks, which involves sending all the 5.13s at the crag in a day (still unclaimed).

At Hueco, there’s the Wanker 101.

The Wanker 101 is a list of one-hundred-and-one boulders on North Mountain, ranging up to V2 but most in the V0 range, that essentially functions as a tour-de-North Mountain and an iconic test piece of volume, skin strength, and planning. These days, a number of the original lines are closed due to proximity to rock art or fragile environmental surroundings, so alternative problems have been chosen to ensure the challenge lives on.

Carrie Cooper, reflecting on her experience completing the challenge in an article for Climbing, highlights how unexpectedly challenging the Wanker is, even if by the numbers it looks trivial. But with that volume of climbing, and romping on beautifully sculpted holds, can come a climber’s high: “It felt like falling in love. Problems 96 to 99 were fantastic, every move a joy. We would rest at interesting holds, 15-plus feet up, no pad, almost singing to one another the beauty of the climb.”

During the 2024-2025 winter season, AAC Hueco Rock Ranch camper Jackson Jewett on-sighted the challenge in a very impressive time of 5 hours 38 minutes.

In recent years, a new challenge has emerged that’s a little more bite-sized, though one climber reflects that “so far, all who've completed it have tasted blood.” The car-to-car format of the No One Runs Out of Here Alive Challenge is familiar, but with a bouldering twist. Competitors bust up the infamous chain trail on North Mountain, top out Nobody Gets Out of Here Alive (one of the most iconic and classic V2s at Hueco) and return to the starting position. The fastest time is currently held by Jake Croft at 6 minutes, 24 seconds.

Of course, other traditions have popped up, shaped by Hueco’s unique environment. One that stands out is the newer tradition of Aoudad Feast.

Aoudads are barbary sheep that roam in and out of Hueco Tanks State Park and the surrounding area. These brown mountain-goat-looking creatures are actually invasive, and have posed a growing problem in the park, due to overgrazing, kicking up soil, displacing native animals, and competing for the same resources. For Aoudad Feast, local climber Billy Heart hunts a few aoudad (outside the park boundaries of course) and provides a meal for local climbers—an excuse to gather and bring attention to the ecological impact of the aoudad, which is often incorrectly attributed to climbers. Appropriately for the desert, the party can get a little weird.

While not necessarily making a dent in this environmental issue, the event is symbolic at the least—these local climbers are tuned in to what matters to Hueco climbing, and how access is complexly intertwined with the landscape’s environmental health.

Hueco, importantly, has a critical role in bouldering history and the cutting edge of the sport. It has become known as a proving ground for climbers of all levels. And it certainly has been the site of many a sending rampage. Though no doubt it requires “paying your dues” to learn the movement and style, the rock also largely rewards strength and power—something plenty of pro boulderers have in spades. For example, Nathaniel Coleman showed up to the AAC’s 2024 Hueco Rock Rodeo and flashed Slashface (V13) and sent Li (V13) and Coeur de Leon (V14), among plenty of other double-digit boulders.

Similarly, Michaela Kiersch had her “best bouldering day ever” at the same Rodeo, reclimbing Crown of Aragorn (V13) and standing atop plenty of other double-digit boulders, like Thrilla in Manilla (V12), Rumble in the Jungle (V12), Phantom Limb (V12), Power of Landjager (V11), and Sunshine (V11).

Matt Fultz, a pro climber known for being down-to-earth with an unusually long wingspan, has been at the forefront of recent hard ascents in Hueco in the last year. Last winter he reopened a climb that previously had been done at V12, located on the left side of the famous Martini Cave. A key hold had broken around 2005, and the route was proclaimed impossible. Fultz was able to reopen the problem again as The Hangover, playing into the martini theme of the area. According to Fultz, it was “probably the most morpho problem [he’s] ever done.” He shares: “I thought the original sequence looked so fun, but was disappointed to hear it was broken and impossible. It wasn’t until last year that I realized I could potentially span the move, but only using every inch of my [six-foot-five] wingspan, along with extra strategy on how I would grip the holds and set up for the move. After a few days of dialing in the sequence, I was able to open up the line again.”

Photo by AAC member Keith Allen Peters.

That same season, Fultz also did the second ascent of Desesperación, and has proposed an upgrade to V15 for the climb, since he thought it was at least a grade harder than its twin, Esperanza (V14). Reflecting on his process, Fultz shares that Desesperación “involves some cryptic moves in and out of a kneebar to some very intense shoulder and tension positions, all through a 60-to-70 degree roof. It’s so cool! It was a pleasure to work out the moves from scratch, as all I had for clues on beta were a couple pictures from the first ascensionist, Martin Mobraten. Projecting Desesperación was different from trying The Hangover in that the biggest challenge was solving the puzzle rather than spanning the moves.”

Of course, Jason Kehl has proved ever-prolific in his ongoing development of boulders in the park, but first ascents on the cutting edge of the sport have slowed down. Fultz thinks that will change in the future: “To my knowledge there is currently nothing harder than V15 that has been climbed at Hueco, but I believe that there is so much potential for harder problems! And with how incredibly talented the upcoming generation of boulderers are, I have no doubt V16 and beyond will come to Hueco in the near future. I think generally people can find Hueco difficult for projecting or having extended trips due to the regulations, but what I’ve found is that they're really not as bad as their reputation.”

Photo by AAC member Michael Lim.