During this unprecedented time of self-quarantines and social distancing many of us have found that we have some extra free time. Time to read. Time to watch movies. Time to plan for the next big trip when things return to normal. The American Alpine Club Library is currently closed to the public indefinitely to limit person to person contact but we will still be doing our best to keep book mail going. If you don’t know about the book mail membership benefit now is the time to become acquainted.

As AAC members you have access to the Henry S. Hall American Alpine Club Library!

This benefit allows you to checkout up to 10 items at a time. We’ll ship the items to you for free! Your only cost is the return shipping. Checkout periods are 35 days and you just have to get the book in the mail heading back to us by the due date.

To checkout books log into your Library profile at: booksearch.americanalpineclub.org First time users will have to notify us to set up their Library account; the best way to do that is for you to send an email to library@americanalpineclub.org and we’ll be able to create your account with the information from the main AAC member database.

We will carry on with book mail as long as there is no link to transferring the virus through the mail and as long as we are able to make it into the Library to ship the materials. If the Denver metro area goes into a shelter in place protocol or another similar quarantine then we will not be able to continue shipping books.

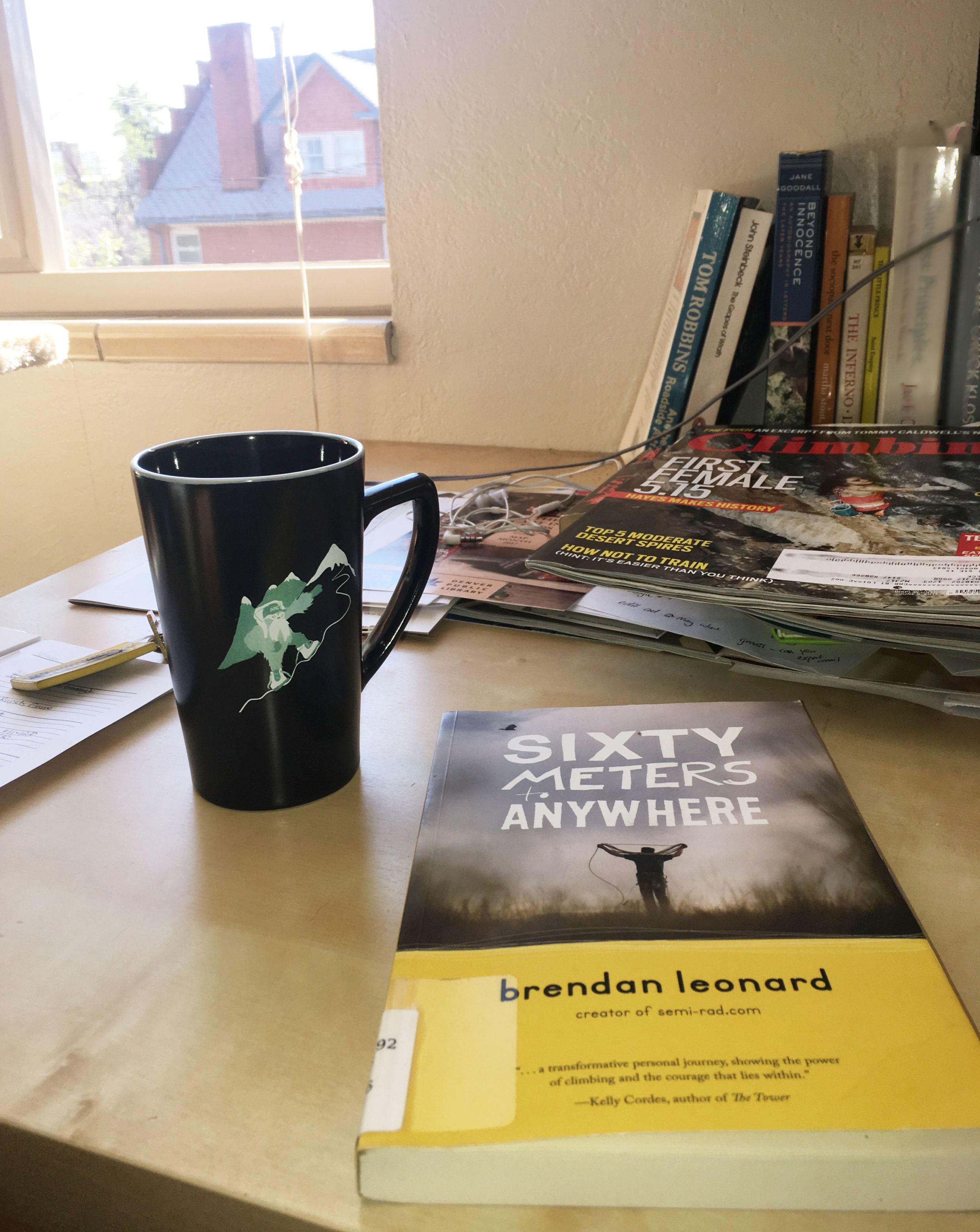

For some ideas on what to read two of our librarians put a list together of some of their favorite books last year for the REI climbing blog which can be seen at https://www.rei.com/blog/climb/aac-librarians-top-favorite-climbing-books Be sure to look at the comments of the post for other great recommendations as well!

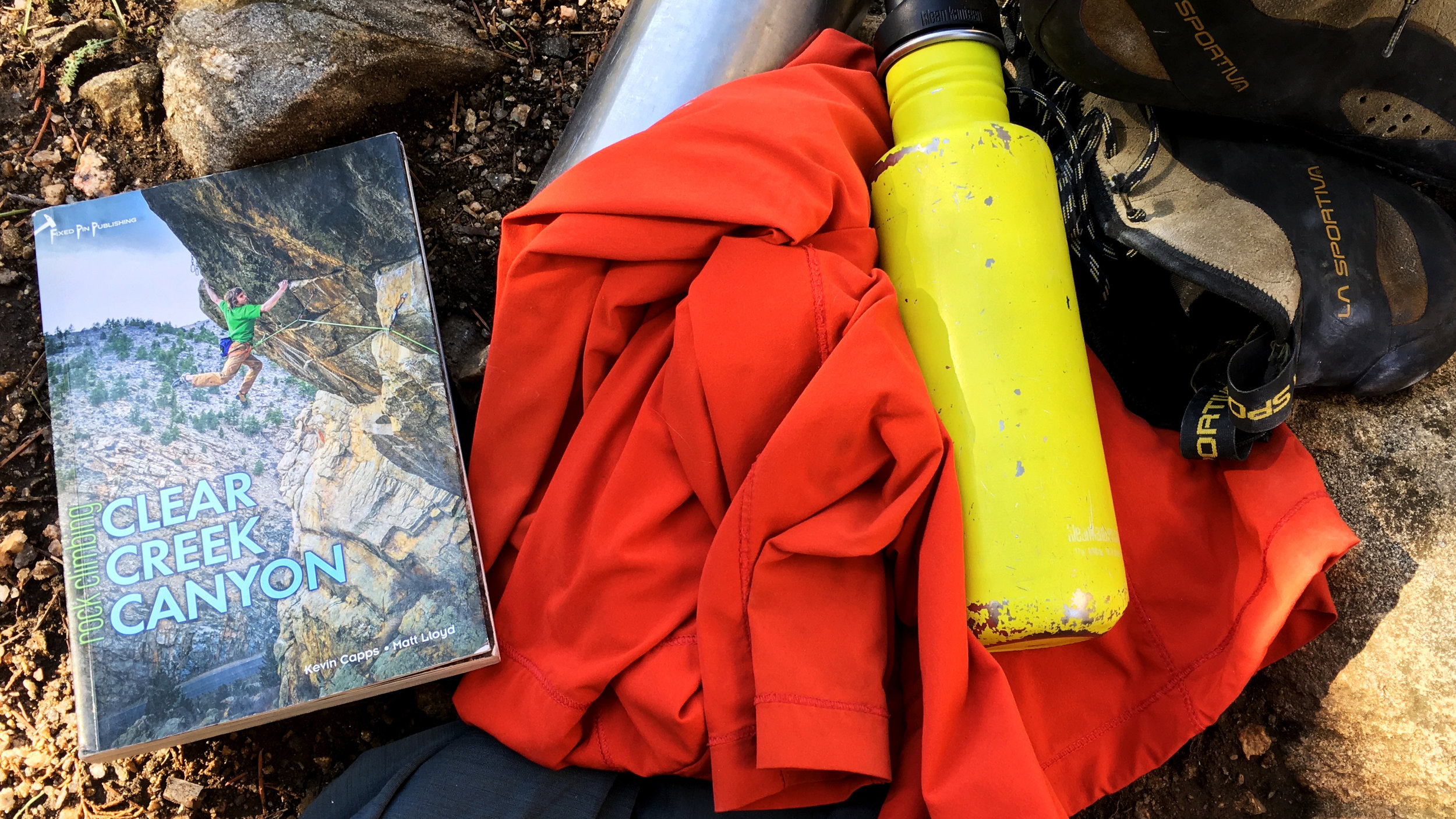

A few of our Utah guidebooks

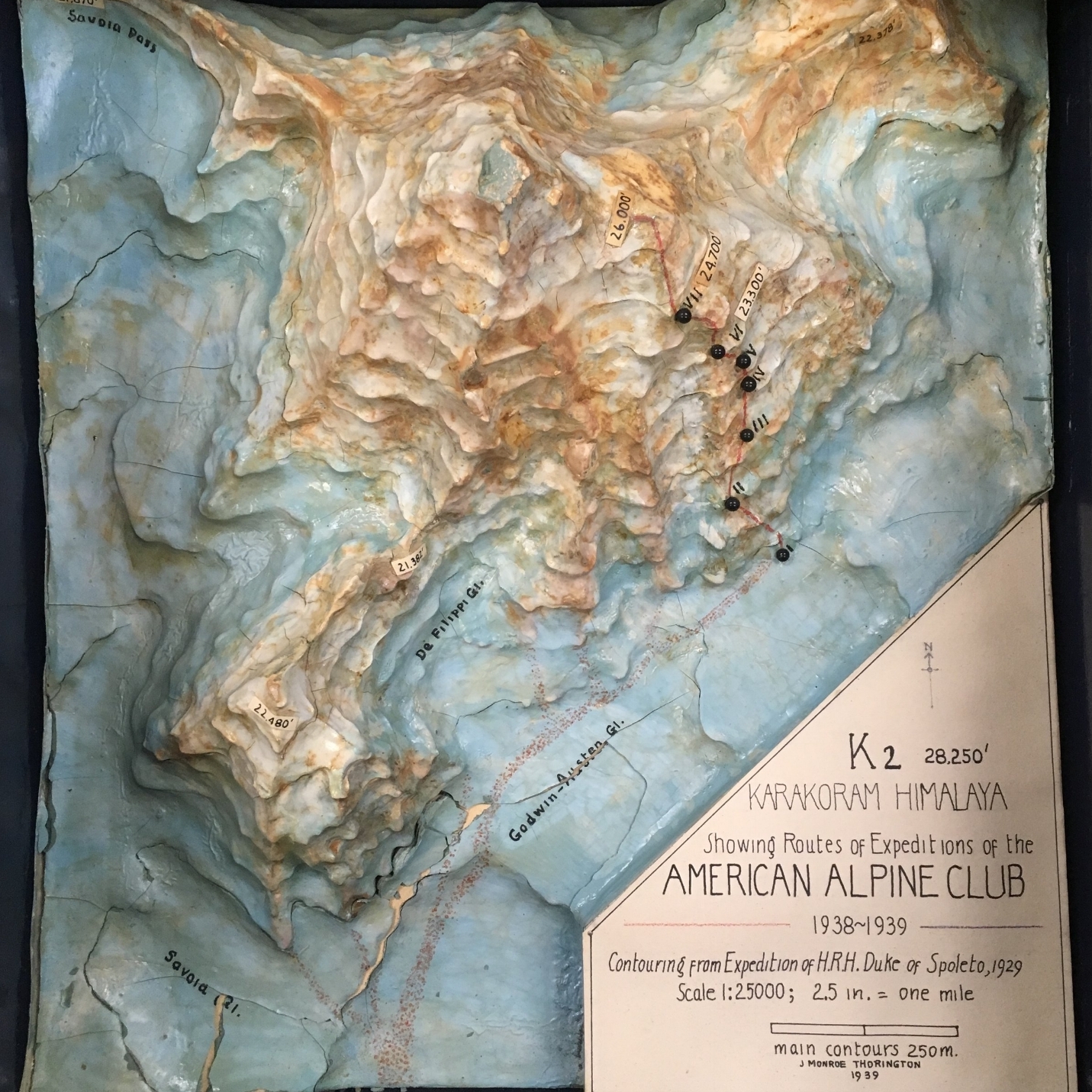

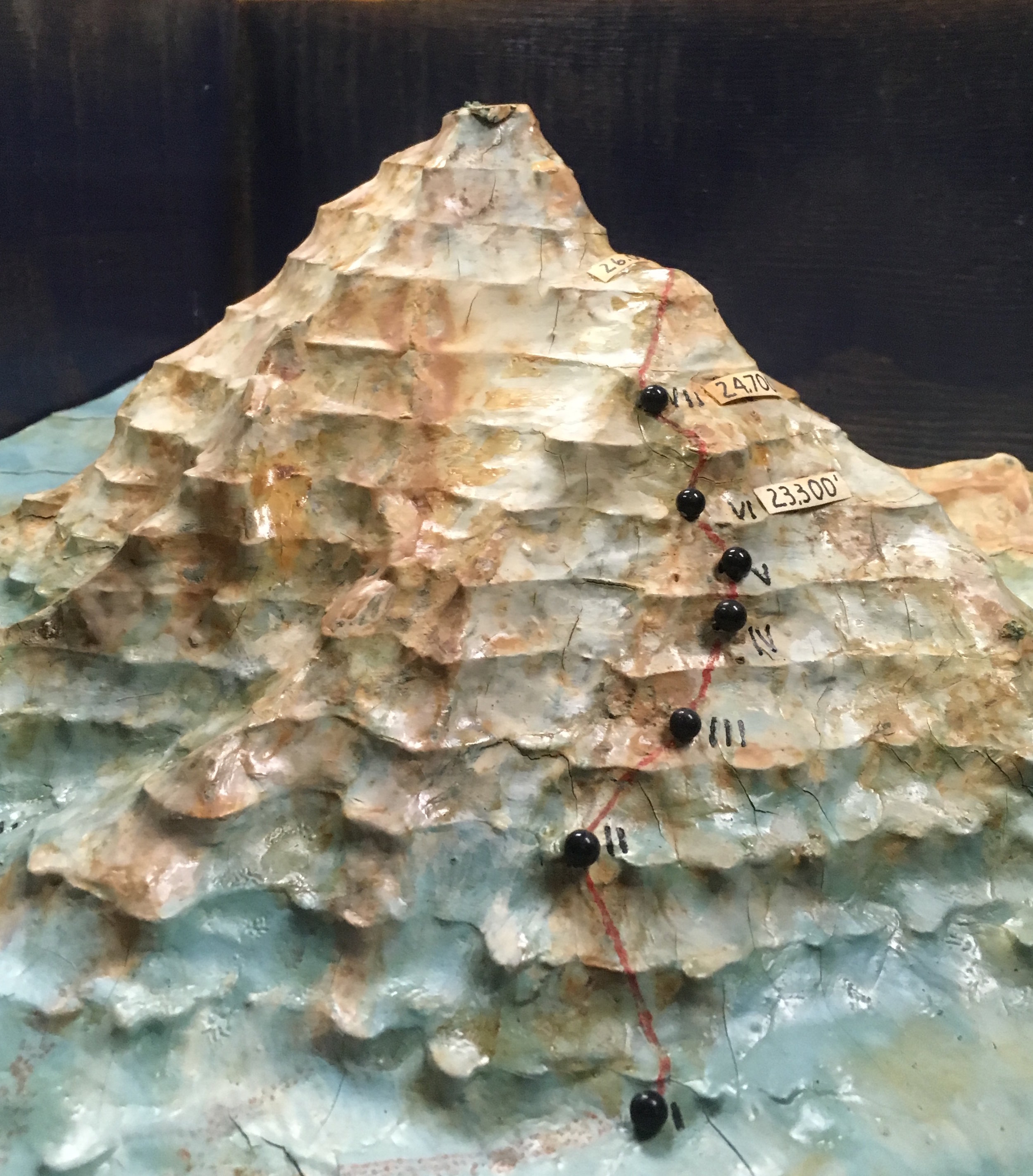

To prepare for your next trip we have both the hiking and climbing guides you need for planning the trip, and we have the how-to-guides that can teach you the techniques you need to know.

Need to learn how to climb?

Not sure what to read or want to recommend a book? Leave a comment below.