By Sierra McGivney, research supported by the AAC Library

Originally Published in Guidebook XVI

Fuller, Miss Fay

Peary, Mrs. Robert E.

Peck, Miss Annie S.A.M.

Workman, Mrs. Fanny Bullock, F.R.S.G.S.

Their names were written in ink, part of the list of founding members of the American Alpine Club in the AAC bylaws and register book. These four women answered Angelo Heliprins' call to establish an “Alpine Society.” The American Alpine Club was established in 1902, but would not get its name until 1905.

The founding members determined that dues were to be five dollars a year, about $186.90 in today's money. This early version of the Club was interested in projecting a reputation of mountain expertise: members had to apply for membership with a resume of mountain climbing or an explorational expedition they had participated in. Those without a sufficiently impressive resume would not be accepted as members. All the founders had lists of their ascents and exploratory expeditions underneath their names to drive the point home that this was a club of high mountain achievers.

It was no small feat that these women were invited to participate in founding an alpine club at the turn of the 20th century. After all, women weren’t allowed in the British Alpine Club until 1974, forcing women to create their own alpine or climbing clubs.

But Fay Fuller, Josephine Peary, Annie Peck, and Fanny Bullock Workman were forces to be reckoned with, each in their own way. They helped steer the American Alpine Club from its beginnings and pushed boundaries in mountain climbing and Arctic exploration, all well before the 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, gave women the right to vote. Each year, their new accomplishments were published in the bylaws and register book under their name, and some were even invited to speak during the AAC Annual Gathering about their expeditions.

Ultimately, these four women are foremothers to American climbing and exploration. Their stories are shaped by their historical context, but the meaning of their mountain achievements is timeless.

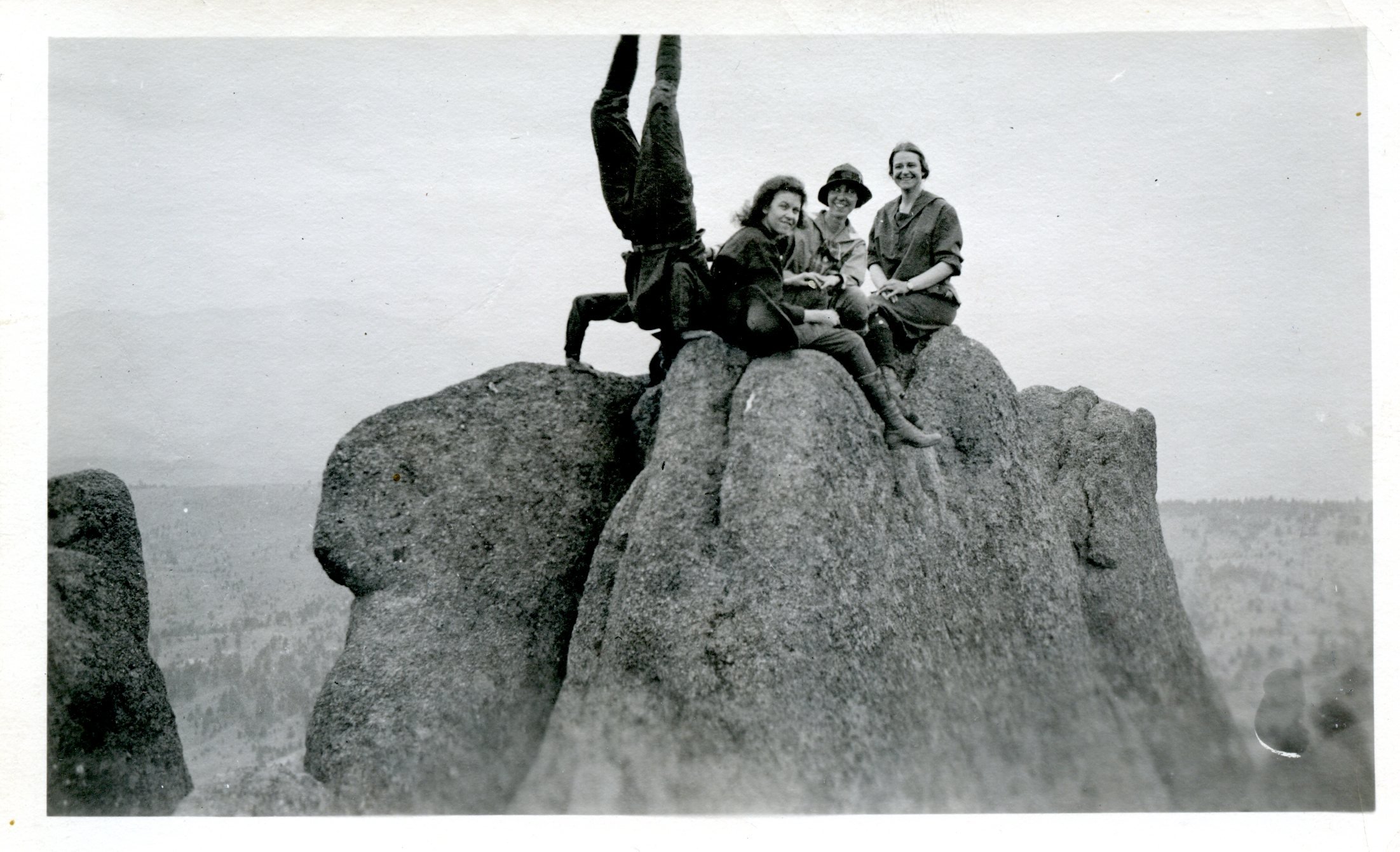

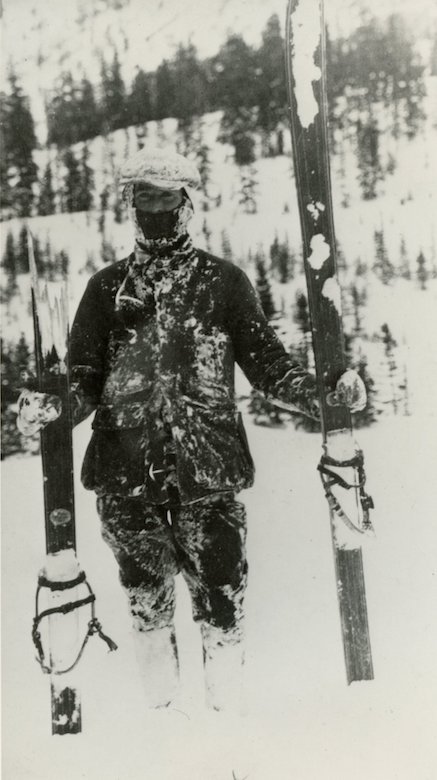

Miss Edwina Fay Fuller was the first woman to summit Mt. Rainier in 1890. Fuller also climbed other glaciated peaks in the Cascades: Mt. Hood, Mt. Adams, Mt. Pitt (now Mt. McLoughlin, which still had a glacier until the early 20th century), and Sahale Mountain. She was described as self-reliant and dogged.

Fay Fuller’s ascent of Rainier nearly ostracized her from Tacoma society—not because she was mountaineering but because of what she wore and who she traveled with.

Her party of five, all men except for her—scandalous for the time—woke up on August 10, 1890, at half past four and began their arduous journey toward the summit. In a 1950 feature article about Fuller in Tacoma’s newspaper, The News Tribune, she said, “I was very nearly ostracized in Tacoma because of that trip—a lone woman and four men climbing a mountain, and in that immodest costume.”

Her “immodest costume,” an ankle-length bloomer suit covered with a long coatdress, was made of thick blue flannel. She also covered her face in charcoal and cream to prevent a sunburn (unfortunately, it didn’t work). Fuller was determined to reach the summit on this attempt, her second up Mt. Tahoma or Tacoma, now Mt. Rainier.

Fuller and her group climbed the Gibraltar Ledges, a Grade II Alpine Ice 1/2 with moderate snow climbing and significant rockfall hazard. Today, the most popular route on Rainier is Disappointment Cleaver, a mix of snowfields, steep switchbacks, and crevassed glaciers, but no technical climbing. Fuller and her team navigated the difficult and exposed terrain of there route with little prior experience and with gear we wouldn’t dare use today, successfully summiting Rainier.

Len Longmire, their guide—though he had never been to the summit—recalled that one of the group members offered Fuller a hand at an especially dangerous place. “No thanks,” she replied, “I want to get up there under my own power or not at all.”

That night, under the stars, the team slept in one of many craters on the stratovolcano, listening to avalanches raging down the mountain. The team continued down safely the next morning, leaving a sardine can containing their names, a tin cup, and a flask filled with brandy as proof of their adventure.

Fuller went on to summit the mountain once more with the Mazamas in 1894.

Her ascent led to her becoming a fierce journalist. She went on to cover the Chicago and St. Louis world’s fairs, and helped found the Mazamas in 1894, the American Alpine Club in 1902, and The Mountaineers in 1906. She became the world’s first harbor mistress in Tacoma and was an actress. Expectations be damned.

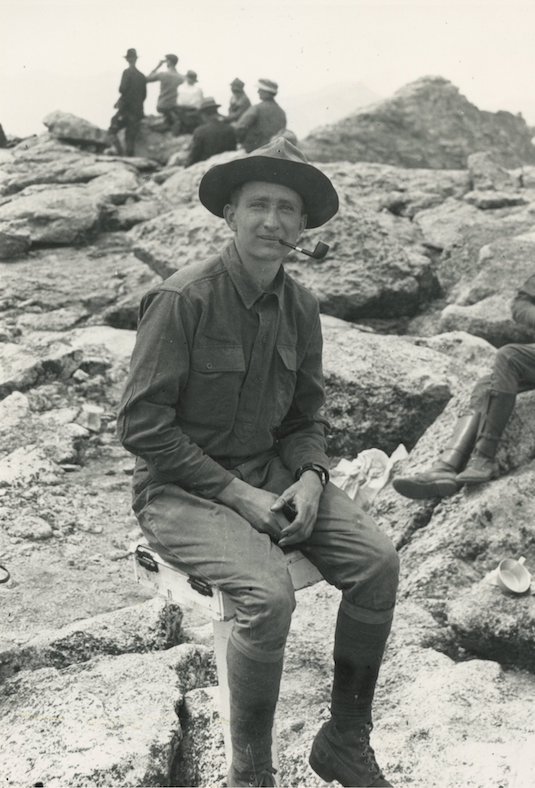

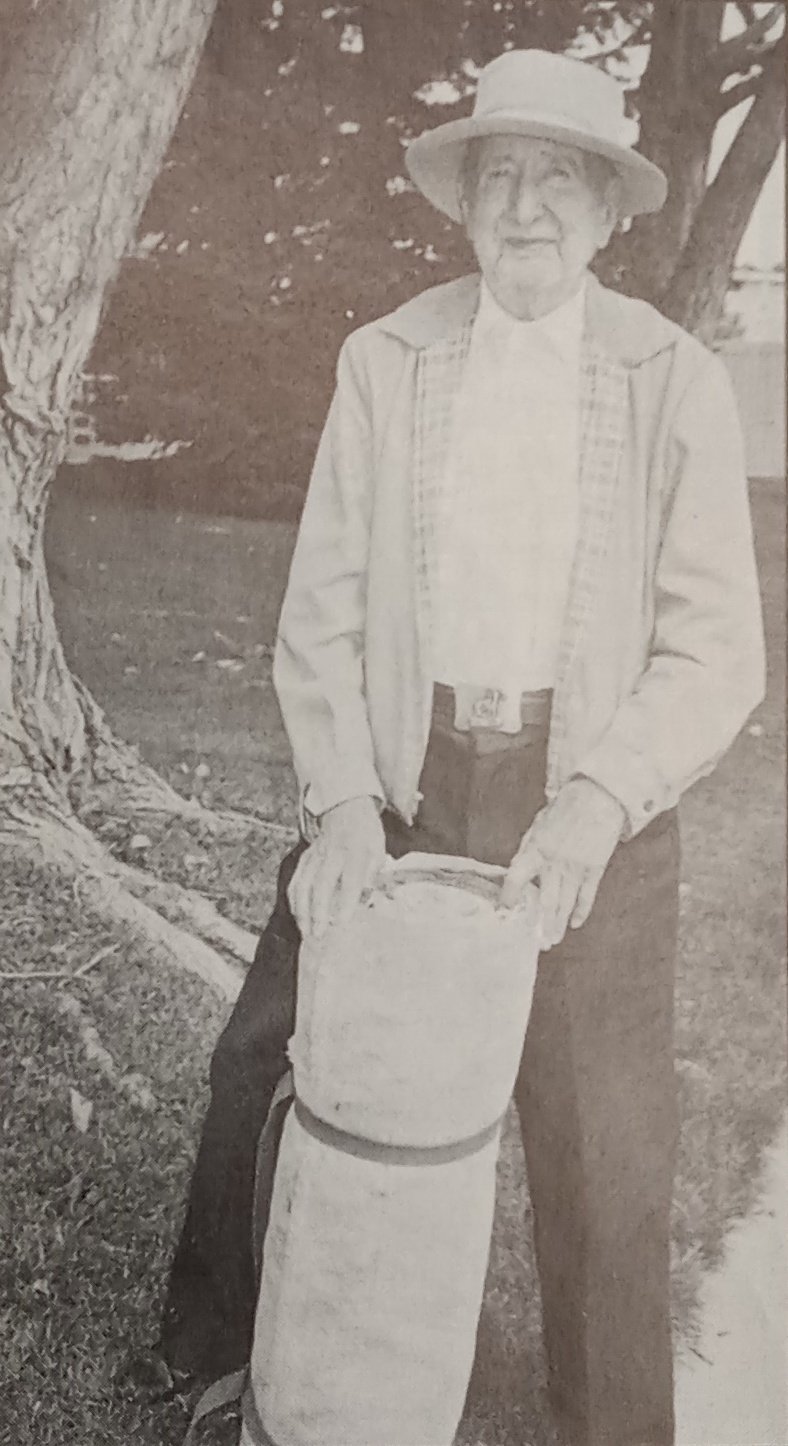

Mrs. Josephine Peary attended Spencerian Business College and graduated as the class valedictorian in 1880. Fueled by her own sense of adventure, she accompanied her husband on four of his Arctic expeditions, learning how to hunt, fighting off walruses, and exploring the breathtaking beauty of Greenland. She was considered the “First Lady of the Arctic” and gave birth to her first child, Marie, about 13 degrees, or just under 900 miles, from the North Pole in 1893.

“I cannot but admire her courage. She has been where no white woman has ever been, and where many a man hesitates to go,” wrote her husband, Robert Peary—who was embroiled in his own controversy in the early 1900s about whether he “discovered” the North Pole and his treatment of the Greenlandic Inuit—in the preface of Josephine’s book My Arctic Journal.

When the American Alpine Club was formed, sport and trad climbing didn’t exist, and ice climbing was extremely primitive. Exploration was nearly as important as mountaineering in defining the sport.

The American Alpine Club’s foundation was based on exploration and mountain climbing. Indeed, included in the 1902 bylaws was the following mission: “The objects of the Club shall be the scientific exploration and study of the higher mountain elevations and of the regions lying within or about the Arctic and Antarctic Circles; the cultivation of the mountain craft...”

Josephine Peary was not a climber. Her expertise was Arctic exploration, which was wholly unknown to the Western world at the time. In 1891, Peary ventured to northern Greenland with her husband and their crew on the Kite. She spent days under the midnight sun gathering yellow arctic poppies and shooting auks, gulls, and eider ducks.

On September 23, Mrs. Peary joined a small group on a smaller boat, the Mary Peary, to head up Inglefield Gulf. They searched for walruses to obtain the ivory in their tusks and meat for the coming winter. At this time, ivory was in high demand, with the United States taking in 200 tons per year by 1913. The devastating effects of the ivory trade on animal populations have made it illegal since 1989.

Robert Peary had brought a Kodak camera and asked the crew members to row until he said stop. He was so engrossed in getting his picture just right—much like a national park tourist—that he forgot to tell them to stop and ran right on top of an ice cake, nearly tipping the boat over. In the chaos, a walrus was harpooned and it dove underneath the water, dragging the boat off the ice cake and righting it.

But the damage was already done. According to Peary, 250 walruses surrounded the boat and bullets started flying. The walruses were not going down without a fight. Bullets whistled by Josephine’s ears in all directions while she reloaded guns.

“I thought it about an even chance whether I would be shot or drowned,” wrote Peary in My Arctic Journal.

This was just the beginning of their time in the Arctic, and danger was all around them, but she was excited by the uncertainty.

Support the Library

The Henry S. Hall Jr. American Alpine Club Library houses one of the world’s finest collections of mountain-related artifacts, archives, rare books, maps, and media. A climbing bibliophile’s dream, the library contains more than 60,000 books and all the information you could ever want on mountain history, mountain culture, climbing routes, and more.

Donate to the AAC Library to support climbing archives and research!

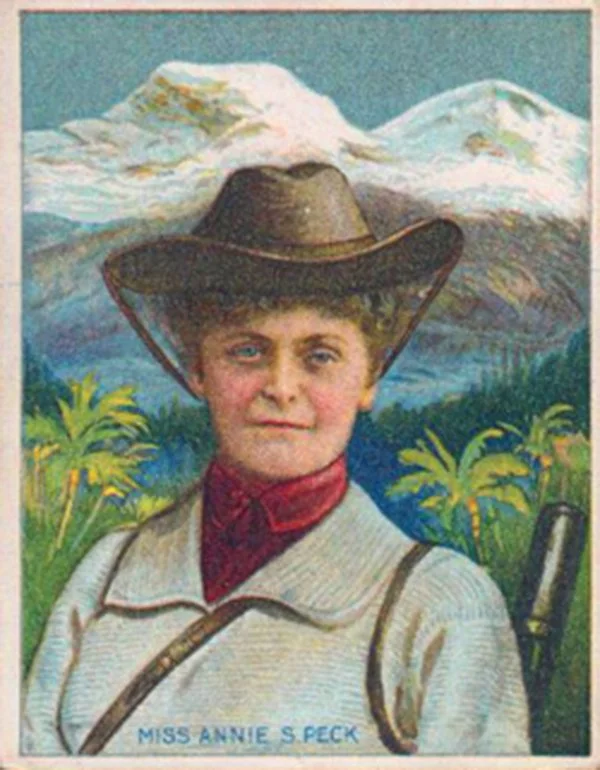

Today, Annie Peck might be best known for wearing knickerbockers on her 1895 ascent of the Matterhorn. According to Peck’s article “A Woman’s Ascent of the Matterhorn” for McClure's Magazine, wearing knickerbockers with or without a short skirt was the norm when “high climbing.”

Annie Peck. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

But not everyone felt this way. Both in and outside the context of mountain climbing, women could face retribution, such as arrest or fines, for wearing pants, but most of the time, they just walked away with damaged reputations or faced social exclusion for their fashion choices. However, some women were arrested for wearing pants and even jailed. Emma Snodgrass, in 1852, was arrested several times for wearing pants in Boston, and Helen Hulick spent five days in jail in 1938 for wearing slacks to a court hearing in Los Angeles.

Peck was a suffragette—whether her pants-wearing was an act of political defiance or a matter of safety, other women had been badly injured or perished while wearing skirts climbing, and she would not be one of them.

“For a woman in difficult mountaineering to waste her strength and endanger her life with a skirt is foolish in the extreme,” wrote Peck in a 1901 article for Outing Magazine titled “Practical Mountain Climbing.”

Peck was a former Latin professor at Smith College who left it all behind to climb mountains and lecture about her adventures. From 1890 to 1910, she climbed a dozen mountains in Europe and Latin America. She would lecture, save up her money, climb mountains, and then repeat the process.

Peck was on the hunt to stand on the apex of America and thought she had found it in Mt. Huascarán in Peru. In 1908, at the age of 58, she successfully summited the mountain on her sixth attempt. She was the first known person to ever stand on top of Mt. Huascarán.

With the help of fellow American Alpine Club member Herschel Parker, a physicist and mountaineer, she determined that the top of the mountain was around 23,520 feet, but she took no measurements from the summit, only the saddle. Peck’s ascent and the associated height she had achieved meant she now held an altitude record, eclipsing Fanny Bullock Workman’s previous record. The claim would start one of the biggest disputes of mountaineering history.

Fanny Bullock. Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

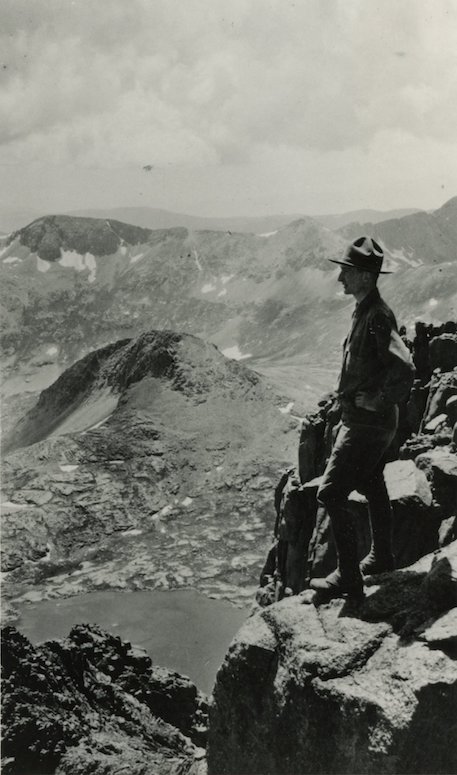

Fanny Bullock Workman was a fierce woman you wouldn’t want to cross. She had an impressive climbing resume, with ascents in the Alps, the Karakoram, and the Punjab Himalaya— she had one of the longer lists of ascents in the AAC’s founders section.

Deeply ambitious, Workman snatched the women’s altitude record from Annie Peck in 1906 when she climbed Pinnacle Peak in the Nun Kun massif in the Himalaya. This spurred Peck to try to take the record back with her climb of Mt. Huascarán, which she claimed to be higher than Pinnacle Peak.

People were engrossed in their feud. The media couldn’t get enough of two powerful women in the same field fighting for the top spot—or rather, the highest spot. Both women gave interviews for articles in newspapers like the Trenton Evening Times, Harrisburg Daily Independent, Detroit Free Press, and Suburbanite Economist, to name a few—defaming one another and trying to frame the story's narrative for their benefit. Whether their feud was malicious or mutually beneficial, people knew their names and accomplishments as mountaineers first, then as women.

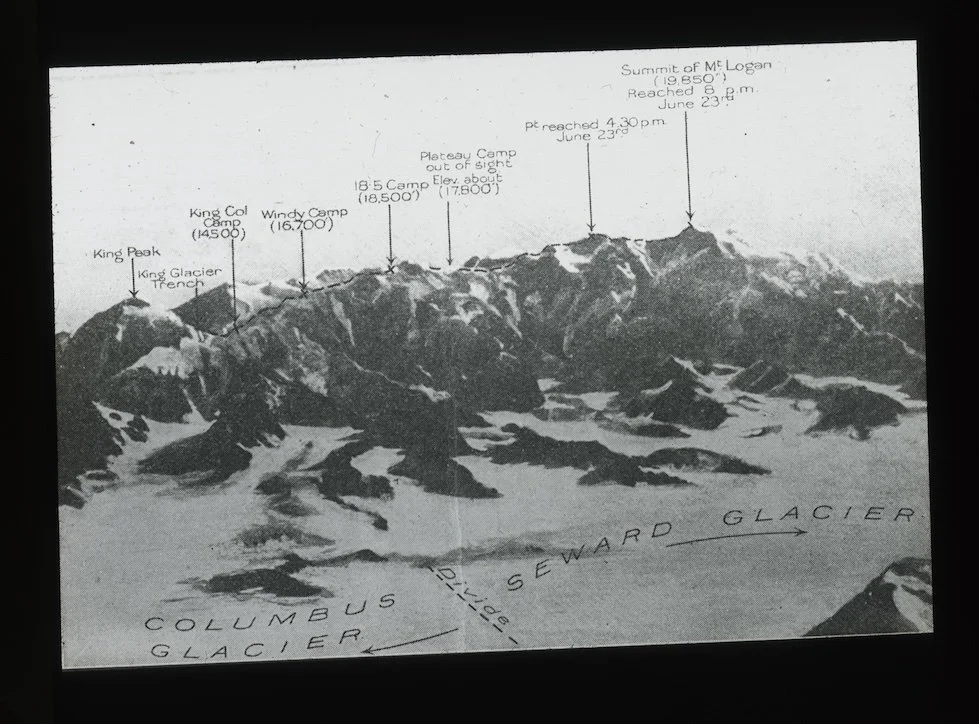

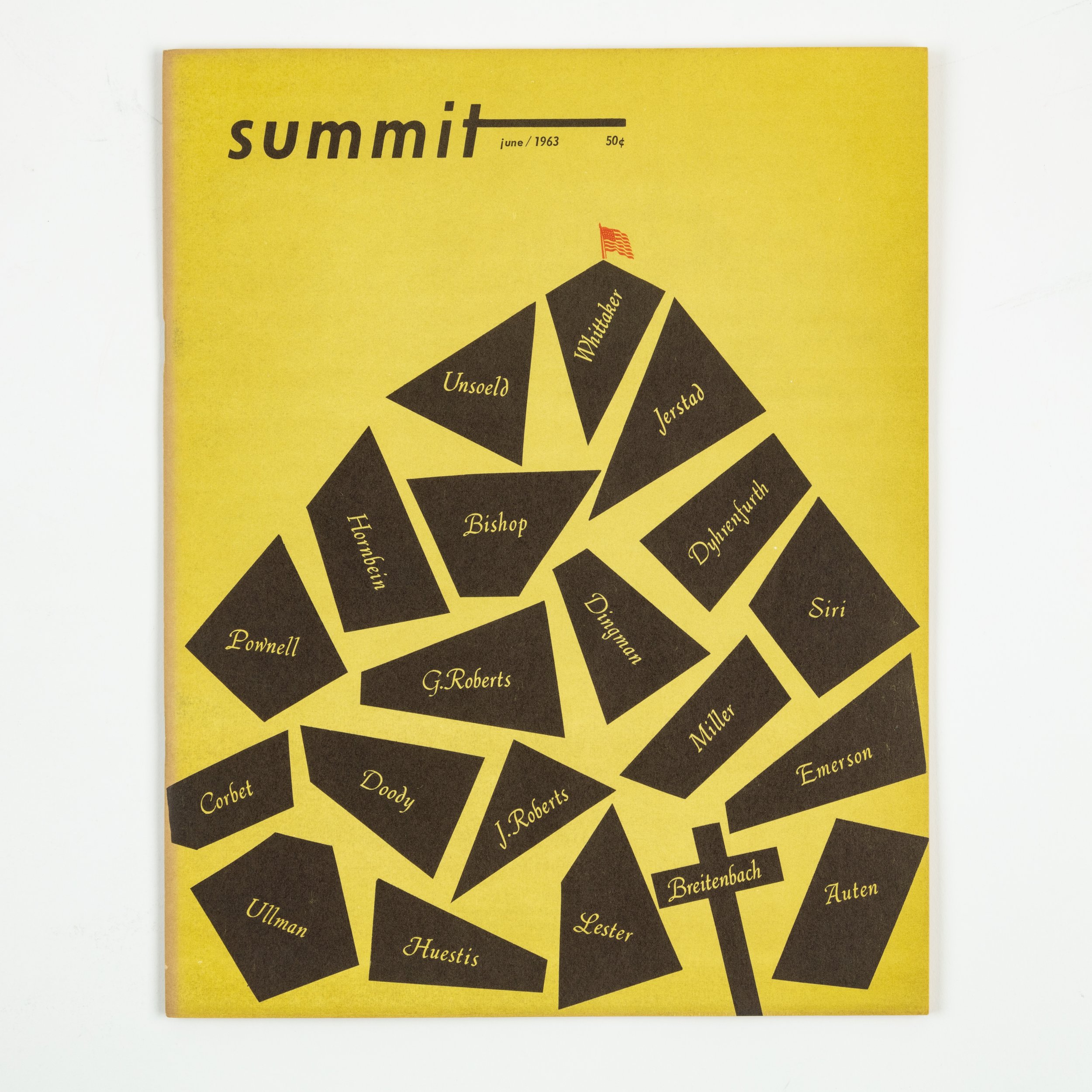

In 1909, the American Alpine Club invited Annie Peck to speak about her ascent of Mt. Huascarán. However, the Club grew concerned when newspaper coverage and fans began to question how she ascertained the height of the mountain. Earlier on the same day of her lecture at the AAC’s annual meeting, Charles E. Fay, Vice President of the AAC, proposed an investigation into the height of Huascarán since “exaggerated reports have recently been circulated by the press...regarding the altitude of Mt. Huascarán.”

News outlets exaggerated the peak’s height to up to 26,000 feet. Peck had not brought an aneroid barometer—a sealed metal chamber that expands and contracts depending on the atmospheric pressure around it—with her on the climb to measure the altitude, nor did she take a measurement from the summit, so she couldn’t be sure about the height.

Workman wanted to end speculation and get her title back. In 1909, she spent the equivalent of half a million dollars to send surveyors to Peru to find the true height of Mt. Huascarán. The surveyors returned with triangulated heights for both the north and south peaks. They determined that the north peak was 21,812 feet (modern technology has determined it is actually 21,831 feet) and the South Peak was 22,187 feet (actually 22,205 feet). Either way, Pinnacle Peak was higher than both.

According to a 1911 New York Times article, the Academy of Sciences ruled in Workman’s favor. The year prior, in a letter sent from Henry G. Bryant, then AAC President, to Annie Peck, Bryant said the AAC sided with Workman’s assessment of the peak’s height. Workman had won back the altitude record, retaining her reign over women’s alpinism.

Caught off guard, Peck didn’t hesitate to make a quippy remark in a letter back to Bryant: “I had not been aware that her interest in my ascent of Huascarán extended so far, though I am not surprised. What fine thing it is to have plenty of money!”

But not all was lost for Peck. In 1910, the Hassan Cigarette Company featured a series of trading cards titled “World’s Greatest Explorers.” Out of 25 cards, Peck was the only woman featured. That same year, the Singer Sewing Machine Company gave away a packet of postcards featuring Peck’s travels and climbing accomplishments with every machine they sold. She still published her book about her expedition on Mt. Huascarán, but switched the title from The Apex of America to A Search for the Apex of America. She was a household name, something money can’t buy.

Still, you wouldn’t have wanted to be seated between Peck and Workman at the American Alpine Club Annual Gathering that year.

These four women helped shape the Club as we know it today. Fuller, Workman, Peck, and Peary were strong-willed, educated women in a world governed by rules and regulations of what a woman should be. Each woman stood defiant in her own way. Fuller was independent. Peary welcomed exploration. Peck believed in safety regardless of norms. Workman was dogged in all of her pursuits. They were courageous and ambitious, petty and imperfect. They were history makers. They were part of something bigger than themselves.