Every year, the AAC bestows awards to climbing changemakers and celebrates their accomplishments at the AAC Gala. We’ll be announcing those award winners in mid July, but first, we wanted to give our listeners a sneak peak into the stories awaiting you, through diving into the life and personality of one awardee. We invited the alpinist and climber Kelly Cordes, who will be receiving the Pinnacle Award this year, onto the pod to celebrate his outstanding mountaineering and climbing achievements, and simply to ramble a bit and tell good stories. Though too humble to brag, Cordes is known for his bold ascents, including the Azeem Ridge on Great Trango Tower, a link-up on Cerro Torre, many first ascents in Peru and Alaska, as well as his “disaster style” and “suffer well” philosophy. With a 20-year lens, we have Cordes reflect on the Azeem Ridge story and tell it anew with all that he’s learned since then. We also spend some time talking about his writing life, including supporting editing the AAJ for 12 years, and co-writing the bestseller, The Push, with his close friend Tommy Caldwell. Dive in to get just a taste of Cordes’ story, and why he’s committed to suffering well.

Guidebook XIV—Member Spotlight

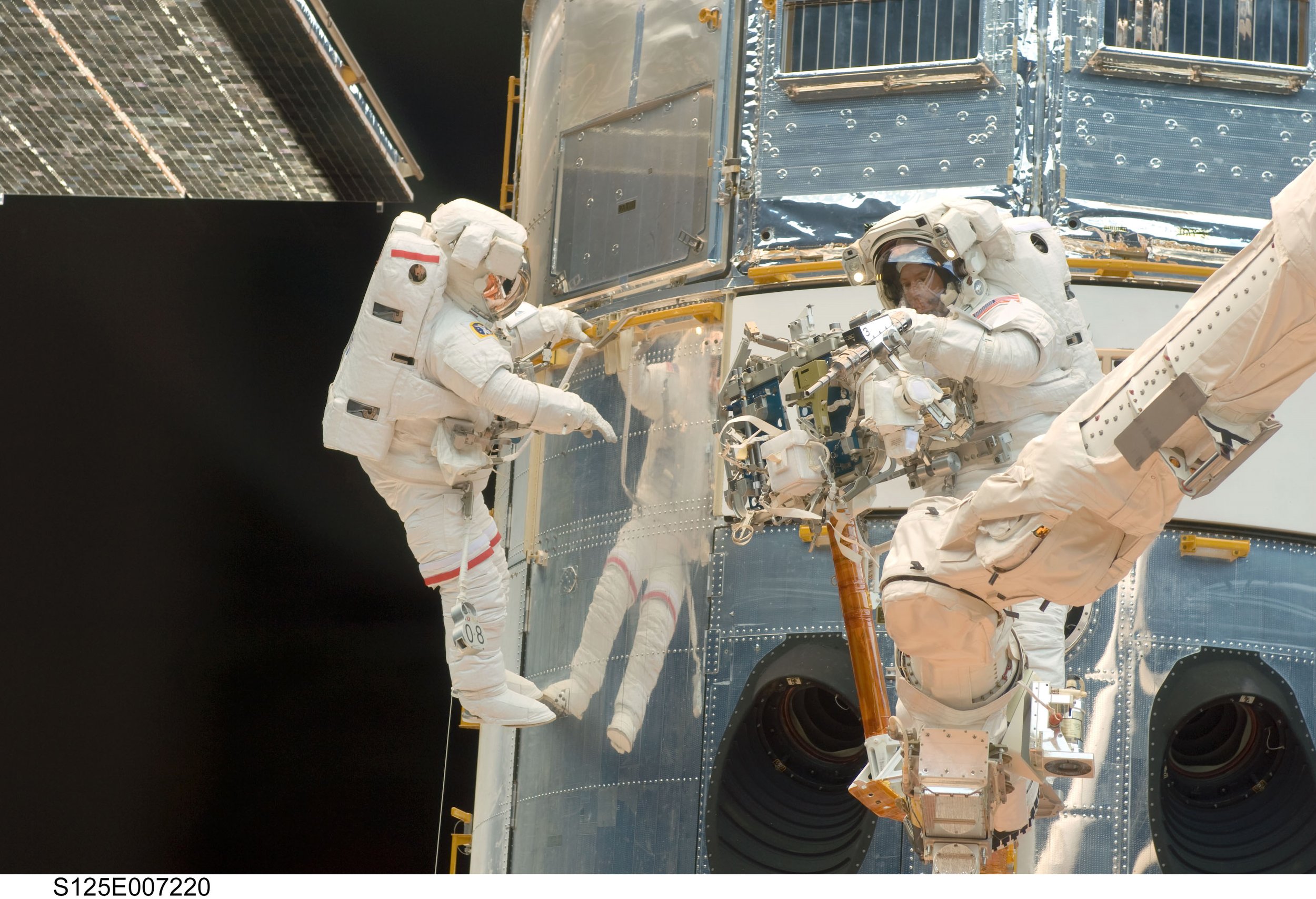

Photo courtesy of the Grunsfeld Collection.

No Mountain High Enough

The Intersections between Space Travel and High-Altitude Mountaineering

Member Spotlight: Dr. John Grunsfeld, Astronaut

By Hannah Provost

Spacewalking outside the Hubble Space Telescope, John Grunsfeld wasn’t that much closer to the stars than when he was back on the surface of Earth, but it certainly felt that way. The sensation of spacewalking, of constantly being in freefall, but orbiting Earth fast enough that it felt like weightlessness, was more of a thrill than terrifying. Looking out to the vaster universe, seeing the moon in its proximity, the giant body of the sun, stole his breath away. Grunsfeld was experiencing a sense of exploration that very few humans get to. It was deeply moving, a sensation he also got in the high glaciated ranges when he’d look around and be surrounded by crevasses and granite walls of rock and ice. Throughout his life, he couldn’t help but seek out the most inhospitable places on the planet, and even beyond.

You might think that there is nothing similar between climbing and spacewalking. But when you ask John Grunsfeld, former astronaut and NASA Chief Scientist—and an AAC member since 1996—about the similarities, the connections are potent.

The focus required of spacewalking and climbing is very much the same, Grunsfeld says. Just like you can’t perform at your best on the moves of a climb high above the ground without intense focus on the next move and the currents of balance in your body, so, too, suited up in the 300-pound spacesuit, with 4.3 pounds per square inch of oxygen, and 11 layers of protective cloth insulation, you still have to be careful not to bump the space shuttle, station, or telescope as you go about the work of repairing and updating such technology—the job of the mission in the first place. Outside the astronaut’s suit is a vacuum, and Grunsfeld is not shy about the stakes. “Humans survive seconds when vacuum-exposed,” he says. With such high risks, it’s a shame that the AAC rescue benefit doesn’t work in space.

Not only is spacewalking, like climbing, inherently dangerous, it also requires intense focus, and it can be a lot like redpointing. Grunsfeld reflects that “it’s very highly scripted. Every task that you’re going to do is laid out long before we go to space. We practice extensively.” In Grunsfeld’s three missions to the Hubble Space Telescope, his spacewalks were a race against the clock—the battery life and limited oxygen that the suit supplied versus the many highly technical tasks he had to perform to update the Hubble instruments and repair various electronic systems. It’s about flow, focus, and execution—skills and a sequence of moves that he had practiced again and again on Earth before coming to space. Similarly, tether management is critical. Body positioning, and not getting tangled in the tether, is important in order to not break something—say, kick a radiator and cause a leak that destroys Hubble and his fellow astronauts inside. But to Grunsfeld, the risk is worth it. The Hubble Space Telescope is “the world’s most significant scientific instrument and worth billions of dollars. Thousands of people are counting on that work.”

Indeed, perhaps a little more is at stake than a send or a summit.

Grunsfeld climbing at Devil’s Lake, WI. Land of the Myaamia and Peoria people. Photo by AAC member Tom Loeff.

Growing up in Chicago, Grunsfeld’s mind first alighted on the world of science and adventure through the National Geographic magazines he devoured, and a school project that had an outsized effect. Grunsfeld’s peers were assigned to write a brief biography of people like George Washington and Babe Ruth. Rather than these more familiar figures, Grunsfeld was assigned to research the life of Enrico Fermi—a nuclear physicist who was instrumental in the Manhattan Project, the creator of the world’s first artificial nuclear reactor, and a lifelong mountaineer. Suddenly, science and the alpine seemed deeply intertwined.

Grunsfeld started climbing as a teenager, top-roping in Devil’s Lake, back when the cutting edge of gear innovation meant climbing by wrapping the rope around your waist and tying it with a bowline. Attending a NOLS trip to the Wind River Range and further expanding on his rope and survivor skills truly cemented his love of climbing in wild spaces. Throughout the years, climbing was a steady beat in his life, a resource for joy. He would climb in Lumpy Ridge, the Sierra, the White Mountains of New Hampshire, Tahquitz, Peru, Bolivia, and many other places with his wife, Carol, his daughter, and close friends like Tom Loeff, another AAC member.

If climbing was a steady beat, his fascination with space and astrophysics would be a starburst. At first, his application to become a NASA astronaut was denied, but in 1992, Grunsfeld joined the NASA Astronaut Corps. It would shape the rest of his life’s work. Between 1995 and 2009, Grunsfeld completed five space shuttle flights, three of which were to the Hubble Space Telescope—which many consider to be one of the most impactful scientific tools of modernity, because of how its 24/7 explorations of space have informed astronomy. On these missions, Grunsfeld performed eight spacewalks to service and upgrade Hubble’s instruments and infrastructure. Over the course of his career, he has also served as the Associate Administrator for Science at NASA and the Chief Scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC. His own research is in the field of planetary science and the search for life beyond Earth.

Grunsfeld [left] and team on the summit of Denali (Mt. McKinley), Denali National Park, AK. Photo provided by Grunsfeld Collection.

But in 1999, even with two space missions under his belt, Grunsfeld couldn’t get the pull of high-altitude mountaineering out of his mind. He has an affinity for the adventure of exploring some of the most adverse places humans have ever explored. He was ready for his next great adventure. He wanted to climb Denali (Mt. McKinley).

Many aspects of Grunsfeld’s Denali saga are familiar. Various trips resulted in unsuccessful summit attempts: from a rope team he didn’t fully trust, to eight days at the 17,000-foot high camp with bad weather. On his 2000 attempt, he was followed around by cameras for a PBS special that never came to fruition, and he attempted an experiment about core temperatures in high-altitude terrain using NASA technology. Ultimately the expedition came back empty-handed—without a summit and with a faulty premise for their measurements of core temperature. When he returned in 2004 with a team of NASA colleagues, Grunsfeld was able to stand atop Denali and take in the jagged peaks all around him.

The connections between climbing and space travel aren’t limited to the physical demand, focus, and calm required. Both activities are inherently dangerous, and nobody participating in either of these activities has been left unscathed. Just like how many climbers have had a friend or an acquaintance experience a significant climbing accident, Grunsfeld knew the true danger of space travel. In 2003 while Grunsfeld was still in Houston, one of the most tragic space shuttle disasters in American space history occurred. On reentry into the atmosphere, the space shuttle Columbia experienced a catastrophic failure over East Texas. According to NASA’s website, the catastrophic failure was “due to a breach that occurred during launch when falling foam from the External Tank struck the Reinforced Carbon Carbon panels on the underside of the left wing.” Grunsfeld was the field lead for crew recovery—picking up the pieces of the disaster so as to bring the bodies of the lost crew members home. It’s no wonder that in other parts of his life and in his climbing, he is deeply committed to safety and disseminating as much climbing knowledge as possible about safety concerns.

After the Columbia disaster, Grunsfeld was often asked why he would consider going back to space when the risks were so high. On his final flight to the Hubble Space Telescope in 2009, Grunsfeld reports, there was a 62% probability that he and his team would come back alive. Those aren’t the most inspiring mathematical odds. But as a crew, and for the agency NASA, it was critical to update the technology on the Hubble Space Telescope at that time. He reflects: “It may seem crazy to fly with those odds, but in fact my earlier missions were much more risky, we just didn’t know it at the time.” In comparison, risk assessment in the mountains is considerably more individualized.

Space exploration and mountaineering also have a distinct investment in monitoring the state of our natural landscapes and environment. From space, it’s a lot easier to see how fragile and small Earth is, in the grand scheme of things. It’s also easier to see the changing climate and its impact across the planet. Putting on his scientist hat, Grunsfeld tried to capture the significance of space observations to climate research, saying, “Most of what we know about our changing climate is now from space observations, because we get to see the whole Earth all the time, and you really have to look at sea level not as a local phenomenon, but [look at] how does it change over a whole Earth for a variety of different reasons.”

From sea level rise to vanishing bodies of water, Grunsfeld has seen some dramatic changes to Earth’s surface from the first time he was in space, in 1995, to his last time in 2009. With his decades of exploration in the mountains, he’s also seen glaciers and once permanent snowfields disappear. You can tell from the passion in his voice that Grunsfeld has a keen awareness of what’s at stake as the climate changes—he’s seen it happening already.

In addition to bringing Grunsfeld to incredible places, climbing also brought him into close connection with incredible people. Grunsfeld had originally met the famous photographer, and fellow AAC member, Brad Washburn through AAC annual meetings and at Boston’s Museum of Science, where Washburn was the director for many years. Their friendship would result in two incredibly rare moments for climbing, photography, and space exploration.

Photo provided by the Grunsfeld Collection.

Washburn, the raspy-voiced photographer who was excellent at pulling off the unbelievable, was working on a documentary recreating the famous journey of the explorer Ernest Shackleton when he called up Grunsfeld for a favor. For the film crew to cross the mountainous, cold, and deeply unfriendly landscape of South Georgia just like Shackleton did in 1916 was still an incredibly unlikely feat. Luckily, Grunsfeld had what you might call “pull.”

“I was able to get space shuttle photography from a classified DOD shuttle flight which flew over South Georgia and made these huge prints for Brad,” Grunsfeld says—ultimately giving Washburn and his team the information they needed to safely traverse this rugged terrain.

But that wasn’t the end of Grunsfeld and Washburn’s story. Grunsfeld was attempting Aconcagua in 2007 when Barbara Washburn called to share the news that her husband had passed away. When Grunsfeld landed back in the States and was able to connect with Barbara on the phone, he offered to do something to honor his relationship with Washburn. His 2009 space mission was coming up, and he could take something of Washburn’s along. In the end, Grunsfeld brought Washburn’s camera from the famous Lucania expedition on his last flight to the Hubble Space Telescope. The 80-year-old camera (at the time) was used to take photographs from Hubble, including an image of the Hubble Space Telescope with Earth’s rim in the background, as seen on the back cover of this Guidebook. Washburn’s camera and the prints of the photos that Grunsfeld took remain as some of the AAC Library’s most fascinating holdings in the climbing archives.

But in fact, Grunsfeld’s (and Washburn’s) story isn’t the first to connect the vastly different fields of astrophysics and mountaineering. Lyman Spitzer, a longtime AAC member and supporter of the Club, and a prolific mountaineer, is credited for the idea that led to the Hubble Space Telescope. It almost makes Grunsfeld’s life’s work seem written in the stars.

Surprisingly, Grunsfeld reflects that there is little time for fear in space travel. Take launch, for example. The astronauts in the space shuttle are sitting on “four and half million pounds of explosive fuel,” says Grunsfeld, ticking down the seconds until they are launched into space. The launch mechanics are so powerful that within eight and a half minutes, the shuttle is traveling 17,500 miles per hour, orbiting Earth. Grunsfeld recalls that on his first mission, sitting in the flight deck of space shuttle Endeavor, at 30 seconds to launch, he heard the final instructions over the intercom: Close your visor, turn your oxygen on, and have a good flight. Was this the point he was supposed to get scared? There was no turning back, no getting off, no stopping the ride. So he didn’t let fear in. There was no use for it. And at the same time, there was so much awe that despite the risk, he felt deeply alive. It was a lot like the calm that comes with executing in the face of danger when climbing or in the mountains. In the face of danger, utter clarity.

With the focus and body awareness and rehearsal, the firsthand witnessing of our changing climate and its impacts, the risks involved and the utter sense of awe, space-walking and climbing are not as different as they might at first seem. And for Grunsfeld, one adventure could fuel another. In his downtime floating within Hubble, one of his favorite activities used to be looking back down on Earth, using a camera with a long lens to zoom in on various alpine regions—and scout the next mountain to climb.

Hand Holds: The Many Cruxes of Parenting and Climbing

In this episode we have Allyson Gunsallus on the podcast to talk about an under-discussed part of the climbing community—the joys and struggles of parenting and climbing. Allyson recently produced Hand Holds, an educational film series now free to watch on Youtube, which cover a range of topics, from shifting identities, logistical challenges, and new relationships to risk as a parent and climber. After all, a toddler waddling around at the crag isn’t just a cute climbing mascot—they can also be a seismic shift in a new parent’s relationship to climbing. The series features Becca and Tommy Caldwell, Beth Rodden, Chris Kalous and Steph Bergner, Kris Hampton, Jess and Jon Glassberg, Majka Burhardt, and Anna and Eddie Taylor. Hand Holds gets into the real (and messy) beta of negotiating life through climbing and parenting, and this episode gets a sneak peak of Allyson’s philosophies and personal experience behind the project.

Sea to Summit

Found in Translation

Life: An Objective Hazard

Zach Clanton’s Climbing Grief Fund Story

by Hannah Provost

Photos by AAC member Zach Clanton

Originally published in Guidebook XIII

I.

Zach Clanton was the photographer, so he was the last one to drop into the couloir. Sitting on the cornice as he strapped his board on, his camera tucked away now, his partners far below him and safe out of the avalanche track, he took a moment and looked at the skyline. He soaked in the jagged peaks, the snow and rock, the blue of the sky. And he said hello to his dead friends.

In the thin mountain air, as he was about to revel in the breathlessness of fast turns and the thrill of skating on a knife’s edge of danger, they were close by—the ones he’d lost to avalanches. Dave and Alecs. Liz and Brook. The people he had turned to for girlfriend advice, for sharing climbing and splitboarding joy. The people who had witnessed his successes and failures. Too many to name. Lost to the great allure, yet ever-present danger, of the big mountains.

Zach had always been the more conservative one in his friend group and among his big mountain splitboard partners. Still, year after year, he played the tricky game of pushing his snowboarding to epic places.

Zach is part of a disappearing breed of true dirtbags. Since 2012, he has lived inside for a total of ten months, otherwise based out of his Honda Element and later a truck camper, migrating from Alaska to Mexico as the seasons dictated. When he turned 30, something snapped. Maybe he lost his patience with the weather-waiting in Alaska. Maybe he just got burnt out on snowboarding after spending his entire life dedicated to the craft. Maybe he was fried from the danger of navigating avalanche terrain so often. Regardless, he decided to take a step back from splitboarding and fully dedicate his time to climbing, something that felt more controllable, less volatile. With rock climbing, he believed he would be able to get overhead snow and ice hazards out of his life. He was done playing that game.

Even as Zach disentangled his life and career from risky descents, avalanches still haunted him. Things hit a boiling point in 2021, when Zach lost four friends in one season, two of whom were like brothers. As can be the case with severe trauma, the stress of his grief showed up in his body—manifesting as alopecia barbae. He knew grief counseling could help, but it all felt too removed from his life. Who would understand his dirtbag lifestyle? Who would understand how he was compelled to live out of his car, and disappear into the wilderness whenever possible?

He grappled with his grief for years, unsure how to move forward. When, by chance, he listened to the Enormocast episode featuring Lincoln Stoller, a grief therapist who’s part of the AAC’s Climbing Grief Fund network and an adventurer in his own right—someone who had climbed with Fred Beckey and Galen Rowell, some of Zach’s climbing idols—a door seemed to crack open, a door leading toward resiliency, and letting go. He applied to the Climbing Grief Grant, and in 2024 he was able to start seeing Lincoln for grief counseling. He would start to see all of his close calls, memories, and losses in a new light.

Photo by AAC member Zach Clanton

II.

With his big mountain snowboarding days behind him, Zach turned to developing new routes for creativity and the indescribable pleasure of moving across rock that no one had climbed before. With a blank canvas, he felt like he was significantly mitigating and controlling any danger. There was limited objective hazard on the 1,500-foot limestone wall of La Gloria, a gorgeous pillar west of El Salto, Mexico, where he had created a multi-pitch classic called Rezando with his friend Dave in early 2020. Dave and Zach had become brothers in the process of creating Rezando, having both been snowboarders who were taking the winter off to rock climb. On La Gloria, it felt like the biggest trouble you could get into was fighting off the coatimundi, the dexterous ringtail racoon-like creatures that would steal their gear and snacks.

After free climbing all but two pitches of Rezando in February of 2020, when high winds and frigid temperatures drove them off the mountain, Zach was obsessed with the idea of going back and doing the first free ascent. He had more to give, and he wasn’t going to loosen his vise grip on that mountain. Besides, there was much more potential for future lines.

Dave Henkel on the bivy ledge atop pitch eight during the first ascent of Rezando. PC: Zach Clanton

But Dave decided to stay in Whistler that next winter, and died in an avalanche as Zach was in the process of bolting what would become the route Guerreras. After hearing the news, Zach alternated between being paralyzed by grief and manically bolting the route alone.

In a world where his friends seemed to be dropping like flies around him, at least he could control this.

Until the fire.

It was the end of the season, and his friend Tony had come to La Gloria to give seven-hour belays while Zach finished bolting the pitches of Guerreras ground-up. Just as they touched down after three bivvies and a successful summit, Tony spotted a wildfire roaring in their direction. Zach, his mind untrained on how fast forest fires can move, was inclined to shrug it off as less of an emergency than it really was. Wildfire wasn’t on the list of dangers he’d considered. But the fire was moving fast, ripping toward them, and it was the look on Tony’s face that convinced Zach to run for it.

In retrospect, Zach would likely not have made it off that mountain if it weren’t for Tony. He estimates they had 20 minutes to spare, and would have died of smoke inhalation if they had stayed any longer. When they returned the next winter, thousands of dollars of abandoned gear had disintegrated. The fire had singed Zach’s hopes of redemption—of honoring Dave with this route and busying his mind with a first ascent—to ash. It would only be years later, and through a lot of internal work, that Zach would learn that his vise grip on La Gloria was holding him back. He would open up the first ascent opportunity to others, and start to think of it as a gift only he could give, rather than a loss.

But in the moment, in 2021, this disaster was a crushing defeat among many. With the wildfire, the randomness of death and life started to settle in for Zach. There was only so much he could control. Life itself felt like an objective hazard.

III.

In January 2022, amid getting the burnt trash off the mountain and continuing his free attempts on Guerreras, Zach took a job as part of the film crew for the National Geographic show First Alaskans—a distraction from the depths of his grief. Already obsessed with all things Alaskan, he found that there was something unique and special about documenting Indigenous people in Alaska as they passed on traditional knowledge to the next generation. But on a shoot in Allakaket, a village in the southern Brooks Range, his plan for distraction disintegrated.

In the Athabascan tradition, trapping your first wolverine as a teenager is a rite of passage. Zach and the camera crew followed an Indigenous man and his two sons who had trapped a wolverine and were preparing to kill and process the animal. In all of his time spent splitboarding and climbing in these massive glaciated mountains that he loved so much, Zach had seen his fair share of wolverines— often the only wildlife to be found in these barren, icy landscapes. As he peered through the camera lens, he was reminded of the time he had wound through the Ruth Gorge, following wolverine tracks to avoid crevasses, or that time on a mountain pass, suddenly being charged by a wolverine galloping toward him. His own special relationship with these awkward, big-pawed creatures flooded into his mind. What am I doing here, documenting this? Was it even right to allow such beautiful, free creatures to be hunted in this way? he wondered.

The wolverine was stuck in a trap, clinging to a little tree. Every branch that the wolverine could reach she had gnawed away, and there were bite marks on the limbs of the wolverine where she’d attempted to chew her own arm off. Now, that chaos and desperation were in the past. The wolverine was just sitting, calm as can be, looking into the eyes of the humans around her. It felt like the wolverine was peering into Zach’s soul. He could sense that the wolverine knew she would die soon, that she had come to accept it. It was something about the hollowness of her stare.

He couldn’t help but think that the wolverine was just like all his friends who had died in the mountains, that there had to have been a moment when they realized they were going to be dead—a moment of pure loneliness in which they stared death in the face. It was the loneliest and most devastating way to go, and as the wolverine clung to the tree with its battered, huge, human-like paws, he saw the faces of his friends.

When would be the unmarked day on the calendar for me? He was overwhelmed by the question. What came next was a turning point.

With reverence and ceremony, the father led his sons through skinning the wolverine, and then the process of giving the wolverine back to the wild. They built a pyre, cutting the joints of the animal, and burning it, letting the smoke take the animal’s spirit back to where it came from, where the wolverine would tell the other animals that she had been treated right in her death. This would lead to a moose showing itself next week, the father told his sons, and other future food and resources for the tribe.

As Zach watched the smoke meander into the sky through the camera lens, the cycle of loss and life started to feel like it made a little more sense.

IV.

After a few sessions with Lincoln Stoller in the summer of 2024, funded by the Climbing Grief Fund Grant, Zach Clanton wasn’t just invested in processing and healing his grief—he was invested in the idea of building his own resiliency, of letting go in order to move forward.

On his next big expedition, he found that he had an extra tool in his toolbox that made all the difference.

They had found their objective by combing through information about old Fred Beckey ascents. A bush plane reconnaissance mission into the least mapped areas of southeast Alaska confirmed that this peak, near what they would call Rodeo Glacier, had epic potential. Over the years, with changing temperatures and conditions, what was once gnarly icefalls had turned into a clean granite face taller than El Cap, with a pyramid peak the size of La Gloria on top. A couple of years back, they had received an AAC Cutting Edge Grant to pursue this objective, but a last-minute injury had foiled their plans. This unnamed peak continued to lurk in the back of Zach’s mind, and he was finally ready to put some work in.

As Zach and James started off up this ocean of granite, everything was moving 100 miles per hour. Sleep deprived and totally strung out, they dashed through pitch after pitch, but soon, higher on the mountain, Zach started feeling a crushing weight in his chest, a welling of rage that was taking over his body and making it impossible to climb. He was following James to the next belay, and scaring the shit out of himself, unable to calm his body enough to pull over a lip. This was well within his abilities. What was happening? How come he couldn’t trust his body when he needed it most?

At the belay, Zach broke down. He was suddenly feeling terrified and helpless in this ocean of granite, with the unknown hovering above him. They had stood on the shore, determined to go as far into the unknown sea of rock as they could, while still coming back. When would be the breaking point? Could they trust themselves not to go too far?

Hesitantly at first, Zach spoke his thoughts, but he quickly found that James, who had similar experiences of losing friends in the mountains, understood what he was going through. As they talked through their exhaustion and fear and uncertainty, they recognized in each other the humbling experience of being uprooted by grief, and also the ability to process and keep going. They made the decision to keep climbing until sunset, swapping leads as needed. Zach was inspired, knowing how shattered he had felt, and yet still able to reach deep within to push through. With the resiliency tools he had worked on with Lincoln, this experience didn’t feel so debilitating.

Yet resilience also requires knowing when to say no, when something is too much. After a long, uncomfortable bivy halfway up a 5,000-foot rock climb, the two decided to start the long day of rappels, wary of a closing weather window.

Zach Clanton and his dog, Gustaf Peyote Clanton, at Widebird. “He [Gustaf] is a distinguished gentleman.” Photo by Holly Buehler

Back safely on the glacier, the two climbing partners realized it was their friend Reese’s death day. Taking a whiskey shot, and pouring one out for Reese, they parted ways—James to his tent for a nap, and Zach to roam the glacier.

The experience of oneness he found, roaming that desolate landscape, he compares to a powerful psychedelic experience. It was a snowball of grief, trauma, resilience, meditation, the connection he felt with the friends still here and those gone. It was like standing atop the mountain before he dropped into the spine, and the veil between this world and those who were gone was a little less opaque. He felt a little piece of himself—one that wanted a sense of certainty—loosen a little. The only way he was going to move forward was to let go.

He wasn’t fixed. Death wouldn’t disappear. Those friends were gone, and the rift they left behind would still be there. But he was ready to charge into the mountains again, and find the best they had to offer.

Support This Work—Climbing Grief Fund

The Climbing Grief Fund (CGF) connects individuals to effective mental health professionals and resources and evolves the conversation around grief and trauma in the climbing, alpinism, and ski mountaineering community. CGF acts as a resource hub to equip the mental health of our climbing community.

Sign Up for AAC Emails

Celebrating AAC Member Bill Atkinson's 100th Birthday

Provided by Holley Atkinson.

Climbing is a powerful force that connects us. Even when climbing takes a backseat in our lives, we are still connected to the people we have partnered with, the places we have climbed, and the impact we have had.

Today, we celebrate the 100th birthday of one of our members, Bill Atkinson. Bill started climbing in the Shawangunks in the late 50's and joined the American Alpine Club in 1978. He was the New England Section Chair and was awarded the Angelo Heilprin Citation Award in 2006 for exemplary service to the Club. He is one of our oldest members and has been a member of the American Alpine Club for 47 years.

Happiest centennial to you, Bill!

Below, you'll find reflections from climbers celebrating Bill's incredible impact and character:

PC: Chris Vultaggio

Bill, your presence in our climbing world has been productive and prolific—and your life has been the same! Your postings have always been inspiring. Thanks for doing all of those. Some segments should be required before being granted membership in the AAC!

We never climbed together – except at the Annual AAC New England Section and some Annual Dinners. That is to say, climbing up to the bar. I'm fifteen years younger, so you were out there ahead of me. But I have you beat on one score! I climbed Mt. Sir Donald via the same route you took, but back in 1962. I was also in the Bugaboos that summer.

You'll be getting a lot of these postings, so I'll keep this short. Thanks again for all you've done for our world. Happy Century! Hang around for another 15 so you can help me celebrate mine.

–Jed Williamson

Happy Birthday, Bill,

You are one very special person, a thoughtful, helpful climber with such an important history of climbing in New England. I respect you and your contributions to the AAC and climbing. Hats off to you, young man. I salute you for your many contributions.

Thank you, and special wishes every day.

Happy Birthday,

Bruce Franks

Rick Merrit celebrates Bill's Birthday by remembering the times they connected through climbing…

Bill was a great section leader as I became more involved in the AAC. He worked hard to recruit and recognize new members through our section's formal dinners. I remember climbing with him on White Horse Ledge in North Conway when he was in his 80s. I also remember hiking with Bill and his friend Dee Molinar when the ABD was at Smith Rock.

Warm regards to Bill,

Rick Merritt

I mainly know Bill through the AAC, specifically the New England chapter, which Bill energetically chaired for many years. We all looked forward to the wonderful black tie annual dinners held in the old Tufts mansion in Weston, MA, that he so carefully organized.

I always enjoyed listening to Bill's extraordinary life experiences, like when he served as a radar navigator in a B52 in the Pacific during WWII, or marveling at his many fascinating inventions and creations, like the beautiful chess boards he crafted and, of course, his amazing climbing career. Bill remained extremely active as a climber long after most of his peers retired, and I remember he climbed the Black Dike when he was 80, I think! That may have been the oldest ascent ever!

I've always appreciated Bill's kind, soft-spoken character and the interest he always showed in others. Bill is a true Renaissance man, and I feel fortunate to know him.

Happy 100th birthday, Bill!

What a milestone!

–Mark Richey

Guidebook XII—Member Spotlight

Josh Pollock “smedging” his way up Con Cuidado y Comunidad (5.6) at the Narrow Gauge Slabs. Land of the Ute and Cheyenne peoples. AAC Graphic Designer Foster Denney

Con Cuidado Y Communidad

By Sierra McGivney

Driving towards Highway 285, we pass strips of red rock cutting through the foothills of Morrison in Colorado’s Front Range, chasing the promise of new climbs. In the front seat, Josh Pollock describes the Narrow Gauge Slab, a new crag he has been developing in Jefferson County.

Pollock is the type of person who points out the ecology of the world around him. As the car weaves along the mid-elevation Ponderosa Pine forest, Pollock describes how we’ll see cute pin cushion cacti, black-chinned or broad-tailed hummingbirds, and Douglas-fir tussock moth caterpillars.

We pull into a three-level parking lot about seven miles down the Pine Valley Ranch Road. With no cell service and heavy packs, we set off along an old railroad trail toward the crag. Not even ten minutes into our walk, Pollock turns off, and we are greeted by a Jeffco trail crew building switchbacks to the crag.

As we approach the base of the Narrow Gauge Slab, Pollock picks up the dry soil. Fine granular rocks sit in the palm of his hand as he describes how this is the soil’s natural state because of Colorado’s alpine desert climate.

Photo by Anne Ludolph.

Unsurprisingly, Pollock was a high school teacher at the Rocky Mountain School of Expeditionary Learning in a past life; now, he is a freelance tutor and executive function coach. A Golden local and climbing developer, he has been working to develop the Narrow Gauge Slab since 2021.

Pollock first became interested in route development in 2011. He wasn’t climbing much then, instead focusing on raising his second child. Flipping through a climbing magazine one day, an article about route development caught his eye.

Between naps, diaper changes, and bottle-feeding cycles, he would go for quick trail runs in the foothills by his house in Golden. During his runs, Pollock noticed cliffs that weren’t in guidebooks or on Mountain Project. He began imagining how future climbers might experience and enjoy the rock.

“The routes I can produce for the community are moderate and adventurous but accessible,” said Pollock.

Climbing in Clear Creek is a high-volume affair. Jeffco Open Space (JCOS), the land management department for Jefferson Country, started to recognize this during the five years from 2008 to 2013 when climbing in the area exploded. With such a high volume of all kinds of outdoor enthusiasts recreating in Jefferson County, including climbers, adverse impacts on the land followed, including increased erosion and propagation of noxious weeds. Previously, Jeffco Open Space took a more hands-off approach when it came to climbing. However, because their mission is to protect and preserve open space and parkland, they concluded the increased popularity of climbing in the area warranted more active management.

While Jeffco Open Space had a few climbers on staff, they quickly realized they were not qualified to make decisions surrounding fixed hardware and route development. They turned to the local climbing community.

In 2015, Pollock began developing routes at Tiers of Zion, a wooded crag overlooking Clear Creek Canyon in Golden. In 2016, Jeffco Open Space established the Fixed Hardware Review Committee (FHRC) with Pollock as one of its seven advisors—now eight. The FHRC provides expert analysis to Jeffco staff members regarding applications for installing or replacing fixed hardware in the area (including slacklining). As a formal collaborative effort between local climbers, route developers, and Jeffco land managers, it is one of the first of its kind in the country.

Eric Krause, the Visitor Relations Program Manager and Park Ranger with Jeffco Open Space, deals with literal and figurative fires weekly and is responsible for all climbing management guidelines. He sits in on meetings and speaks for Jeffco.

“I think really good communication between a landowner or land manager and the climbing community is imperative,” said Krause.

Since 2015, Jeffco Open Space has invested more than 1.5 million dollars to improve the access and sustainability of existing crags by stabilizing eroding base areas, building durable and designated access trails, supplying stainless steel hardware to replace aging bolts, supplying portable toilet bags to reduce human waste at crags, and rehabilitating unsustainable areas.

If new routes for an existing crag are submitted to the FHRC via their online form, it’s already an impacted area, so it’s more likely to be approved. During their quarterly meeting, each member of the FHRC reviews the submission and discusses whether the new route(s) is a worthwhile addition to climbing in Jefferson County. A route that might be denied is within the 5.7-5.10 range at a crag with limited parking and heavy trail erosion, because routes in that range tend to attract the highest volume of climbers.

“We don’t really want to be adding more sites that are just going to degrade, and we’d rather get in there ahead of time and build it out to where it’s sustainable to begin with,” said Krause.

If a new crag is submitted, this triggers an entirely different internal review process called the “New Crag Evaluation Criteria (NCEC),” overseen by Jeffco Open Space. Every individual on the JCOS internal climb- ing committee (comprised of staff from the Park Ranger, Trails, Natural Resources, Planning, Park Services, and Visitor Relations teams) independently rates the new crag based on various categories: potential access trails, environmental considerations, parking, traffic, community input, organizational capacity, visitor experience, and sanitation management. They then average all of the scores for the submitted crag, and its viability is discussed.

To combat the ever-growing need for accessible places for new climbers, families, guided parties, and folks looking for high-quality moderate climbing, Jeffco asked the FHRC and others if they could find a beginner-friendly new crag in the southern part of the county, where there are fewer climbing areas.

According to Krause, Pollock took this request to heart and started looking all over the county for a new crag. He struggled to find a place with adequate parking, access to bathrooms, and the ability to build new trails on stable ground. “Threading that needle is hard, and it took several years and maybe half a dozen possible locations to find one that worked,” said Pollock.

An open space staffer suggested he look at the area that is now the Narrow Gauge Slab.

When Pollock first walked along the base of what would become a major project in his life, the Narrow Gauge Slab, he felt compelled by the rock’s position, composure, and aesthetic. He began imagining routes to climb. The crack features broke the wall up into clean-looking panels.

For Pollock, unlocking the potential of a crag is an unanswered question until the last moment.

“There’s a great drama to it,” said Pollock.

He proposed the crag in 2021. The Narrow Gauge Slab would become the first crag approved under the NCEC framework.

“I think what I’m most excited about is that this whole endeavor has been collaborative and cooperative with Jeffco Open Space from the get-go,” said Pollock.

Jeffco is constantly playing catch up with erosion damage in an arid climate like the Front Range. At the Narrow Gauge Slab, Jeffco had the opportunity to identify and implement adequate infrastructure for the area before route development began.

“In some ways [it is a] first of its kind experiment, with building a sustainable access trail and stabilizing belay pads on the base area and things like that before lots of user traffic shows up,” said Pollock. The Boulder Climbing Community, the AAC Denver Chapter, and Jeffco collaborated to stabilize and build out the area before the crag opened to the public.

According to Pollock, the crag does not have a theme. Since this crag has many developers, and sometimes multiple developers to any given climb, the route names have personal meaning to the developers or the circumstances of the route. But when you look closely, a kaleidoscope of meaning comes into view: collaboration.

His primary objective with the Narrow Gauge Slab was to develop a moderate and accessible crag, but the project evolved into something much more: mentoring climbers on route development. He reached out to different LCOs, such as Cruxing in Color, Brown Girls Climb Colorado, Escala, Latino Outdoors, and the AAC Denver Chapter, inviting members to participate in a mentorship program based on route development. In total, there are 16 mentees and five mentors, plus Pollock. Despite uncovering the crag, Pollock has barely put any hardware in.

Route development is a niche aspect of climbing that requires extensive resources and knowledge. Pollock wanted to invite new groups of climbers who might not consider themselves route developers but were interested in learning. He is pleased that the mentees have learned from this project and are developing new routes near the Front Range. Some mentees have been swallowed whole by the development bug. Lily Toyokura Hill is so enthused that she was recently appointed to the nearby Staunton Fixed Hardware Review Committee.

Photo by Anne Ludolph.

Hill and Ali Arfeen collaborated on Bonsai, a 5.7 climb featuring a tiny tree sticking out of the rock. Hill, who is shorter, and Arfeen, who is taller, would take Pollock’s kid’s sidewalk chalk and mark key holds they could reach, helping to determine where they would place bolts when they were developing the route’s first pitch.

To the left is Con Cuidado y Comunidad (With Care and Community), a three-pitch 5.6 put up by (P1) Sharon Yun and AAC employee Xavier Bravo, and (P2+3) Maureen Fitzpatrick and Cara Hubbell.

While Pollock racks up to lead Con Cuidado y Comunidad, Douglas-fir caterpillars inter- rupt our conversation. Pollock stops, pointing out the fuzzy horned creature on his bag. He describes how their population erupts every seven to ten years. His father was a biology teacher, and both of his children are fascinated by ecology.

On top of Con Cuidado y Comunidad, we picnic overlooking the epic landscape of the South Platte. Pollock explains how climbing at the Narrow Gauge Slab requires what he calls “smedging,” a mix of smearing and edging.

Climbs are littered with minuscule footholds and often require both smearing and edging to climb. Pollock prefers this type of movement: slow and thoughtful.

The last bolt for the Narrow Gauge Slab was drilled on August 19, just in time for opening day on the 24th. Pollock feels immense pride in the crag.

“It is really satisfying to share the crag with folks and give to the community,” said Pollock.

On these south-facing slabs, there are thirteen routes ranging from 5.4 to 5.9+, spread across the crag’s granite rock. You can listen to the babble of the South Platte River as you climb, breathing in the smell of fresh pine needles as you stand up on a tiny food hold. Don’t forget to look out for the Douglas-fir caterpillars inching their way across the rock as you clip the bolts.

Support This Work— Join or Give Today

Your contribution will significantly impact climbers—whether they are learning how to avoid accidents through our updated database, using research funding to analyze melting ice caps and the changing heights of iconic mountains, or pursuing first ascents around the world. Your gift makes these things possible.

CONNECT: The Next Generation of Crag Developers

The mentorship gap is a frequent topic of discussion in a lot of climbing circles, and the gap seems to be especially pronounced for climbers trying to get into crag and boulder development. In this episode, we dove into the joys of having too many mentors to count.

Long-time developer and AAC member Josh Pollock decided to collaborate with Jefferson County, in the Front Range of Colorado, to develop a beginner-friendly crag called the Narrow Gauge Slabs. For this project, sustainability and accessibility was a focus from the start, and Josh and other local developers designed a mentorship program that would coincide with developing the crag, to support climbers of traditionally marginalized backgrounds who want to equip themselves with knowledge and mentorship resources so that they could be developers and mentors in their own right. In this episode, we sat down with Lily Toyokura Hill and Ali Arfeen, two mentees in the program who have really taken this experience and run with it, stepping into leadership roles in the local climbing community. We cover what inspired them to become developers, perceptions of route development and who belongs, grading and individual bolting styles, and much more. The conversation with Lily, Ali, and Josh illuminates a lot about the power of mentorship and the complex considerations of developing in modern climbing.

CONNECT: Undercover Crusher Nathan Hadley

On this edition of the Undercover Crusher series, we have Rab athlete Nathan Hadley on the pod. We talk about what counts as “undercover,” and the reality of straddling the world of full-time work while being “pro.” We discuss the pressure to be obsessed with Yosemite, and maybe figuring out that performing in Yosemite is not the only place to make a name for yourself…as well as bolting and development ethics in Washington, sending the Canadian Trilogy, and the downsides and upsides of being a route setter.

Jump into this episode to hear all this and more from crusher Nathan Hadley!

CONNECT: Summiting Denali, Living the Dream

In this episode, we had Live Your Dream grant recipient John Thompson on the pod to tell us all about his trip to Denali! Our Live Your Dream grant is our most popular grant, and it’s powered by The North Face.

John’s LYD story is about feeling a sense of urgency–how now is the time to explore and pursue big adventures. A strong sense of carpe diem. After nearly a decade away from Denali, John returned, only to get caught up in helping with a rescue, and not getting to pursue his goal route because of weather conditions. We sat down with John to hear about his grant experience, the rescue he helped with, his journey falling away from climbing and coming back to it, how guiding shaped his climbing, and why it meant so much to be standing on the top of Denali once again.

Pay What You Can (PWYC) Toolkit

At the AAC, we believe that addressing equity issues in climbing is not mutually exclusive from best business practices. That is why, in partnership with The North Face, we designed a Pay What You Can (PWYC) toolkit, a free resource for gyms who want to offer alternative payment models alongside—or in place of—traditional membership structures. Although much of our work at the AAC is outdoor-centric, we recognize that many climbers are introduced to the sport through a gym, and therefore a holistic approach to climbing access requires us to consider challenges across the climbing spectrum, including indoor climbing. Our hope is that with our toolkit, gyms can implement sustainable PWYC models that offer a product that is attainable for those in under-represented income brackets, with the added benefit of increasing these gyms’s memberships and maintaining a profitable business.

We examined 47 existing Pay What You Can (PWYC) programs within the climbing gym industry, interviewing 16 program leaders for further study, in order to analyze the viability and best practices of PWYC programs. While PWYC programs take on many forms, they all share an essential goal: to provide financial options for individuals and families who are otherwise unable to afford a gym’s day pass or membership at “standard” rates.

In this toolkit you will find:

Analysis of the nine (9) components that comprise PWYC programs

Two (2) case studies based on the experience and outcomes of real gyms

Insights and Best Practices

FAQs

Resources, including a grant to support the one-time cost of implementing a PWYC program, a peer-to-peer directory of gyms implementing PWYC programs, and an example application (if the model you are considering utilizes a “proof of need” application).

In the climbing gym industry and looking to start your own PWYC program at your gym? Explore the PWYC grant to get started!

Powered By:

All Aspects

The AAC DC Chapter hosts a New Ice Climber Weekend in the Adirondacks with Escala

PC: Colt Bradley

Grassroots: Unearthing the Future of Climbing

By: Sierra McGivney

The sun peeked over the Pitchoff Quarry crag, hitting the ice and creating an enchanting aura. The cool February air was saturated with people laughing and ice tools scraping against the ice. If you listened closely, you'd notice that the conversations were a beautiful mix of English and Spanish.

PC: Colt Bradley

The New Ice Climber Weekend (NICW), hosted by the AAC DC Chapter, has become an annual event. Piotr Andrzejczak, the AAC DC chapter chair and organizer of the New Ice Climber Weekend, believes mentorship is paramount in climbing. The weekend aims to provide participants with an opportunity to try ice climbing, find ice climbing partners, and have a starting point for more significant objectives. Above all, it aims to minimize the barrier to entry for ice climbing.

Last year, Andrzejczak approached Melissa Rojas, the co-founder of Escala and volunteer with the DC Chapter, about partnering to do a New Ice Climber Weekend with Escala. Escala is part of the American Alpine Club's Affiliate Support Network, which provides emerging affinity groups with resources in order to minimize barriers in their operations and serving their community. Escala “creates accessibility, expands representation, and increases visibility in climbing for Hispanic and Latine individuals by building community, sharing culture, and mentoring one another.”

Climbing can be a challenging sport to get into. It can require shoes, a harness, a gym membership, and climbing partners. Ice climbing requires all that plus more: ice tools, crampons, and winter clothing.

"There's a lot more complexity to ice climbing," said Rojas.

PC: Colt Bradley

Ice climbing can be limited not only in quantity but also in quality. Due to climate change, the ice in the Adirondacks loses its quality faster than previous decades and the climbs are only of good quality for a limited amount of time. DC climbers are at least seven hours from the Adirondacks, plus traffic and stops, so ice climbing for them has unforeseen logistical challenges. During the NICW, participants can focus more on the basics of learning to ice climb and less on logistics.

Rojas and Andrzejczak hosted a pre-meetup/virtual session so that participants could get to know each other and ask questions ahead of time. "We wanted to give folks an opportunity to ice climb in a supportive environment where they felt like they were in a community and were being supported throughout the whole process, from the planning stage to the actual trip," said Rojas.

Another focus of the weekend was creating a film. Colt Bradley attended the New Ice Climber Weekend in 2023 as a videographer and as a participant. Bradley volunteers with the AAC Baltimore Chapter and is also Andrzejczak's climbing partner. Last year, he created four Instagram videos that captured the excitement of ice climbing for the first time. When asked to film the Escala x NICW this year, he wanted to do something longer and more story-focused. Bradley and Rojas talked beforehand about focusing the film on the Escala community and highlighting the bond made possible through its existence.

Rojas has worked hard to build up this blended community of Spanish-speaking climbers. Spanish has many flavors, as it is spoken in many different countries with different cultures—all unique in their own way. The film focused on reflecting and representing the vibrant community of Escala.

Soon, they all found themselves at Pitchoff Quarry in the Adirondacks. While the participants learned how to swing their ice tools and kick their crampons into the ice, Bradley sought out community moments. He wanted to put viewers in the moment as participants climbed, so he mic'd some participants; including Kathya Meza.

Meza spoke openly during interviews and had a compelling story that Bradley thought would resonate with the viewers.

PC: Colt Bradley

In the film's final scene, viewers can hear Meza swinging her tools into the ice, see her smiling, and experience her problem solving as she pushes herself outside her comfort zone. Bradley filmed this scene the first day before they even identified her as a focal point of the film.

Bradley continued to capture the essence of the Latino influence over the weekend. On the second day, the group headed to Chapel Pond. Despite the cold 21-degree weather and whipping wind, the energy was high. Mentors taught mentees how to layer correctly, and folks danced salsa at the base of the crag to stay warm. Later, feeling connected and energized from this incredible trip, the group salsa danced on the frozen Chapel Pond with the iconic ice falls that makeup Chounaird's Gully and Power Play in the background.

"For the twenty-some-odd years I've been going to the Adirondacks to ice climb, I've never even thought that maybe one day I'll be dancing on Chapel Pond, hosting a new Ice Climbing weekend with Escala" said Piotr.

For Rojas, it was some of her best salsa dancing. She was so focused on staying warm that it freed her from overthinking her dancing skills. The dancing didn't stop at Chapel Pond. After dinner, the group returned to the inn and fired up the woodstove in the recreation room. The sound of salsa dancing and glee filled the room.

The NICW isn't about going out and sending, so naturally, this isn't the type of climbing film where climbers try hard on overhung climbs overlaid with cool EDM music. Every climber remembers the moment they got hooked on climbing, whether sport, trad, ice, or alpine climbing; they remember the thrill of reaching the top of a climb for the first time, out of breath but more excited than ever. Climbing is a multifaceted sport, and climbing films should be reflective of that. Showing the first-time-swinging-an-ice-tool moments at the NICW inspires someone to take that first step toward something new or nostalgic for the longtime climber.

PC: Colt Bradley

"I think the thing about Escala is it's more than just a climbing group. It's a community," said Rojas.

Escala is a place where Rojas can be all parts of herself. Rojas has four children and refers to Escala as her fifth baby. She doesn't have to explain why she climbs or her love for Sábado Gigante–a famous variety show in Latin America. Everyone in her community recognizes all aspects of her. Her identity as a climber and as a Latina can be one.

One participant of the NICW approached Rojas and said it was the best experience of their life.

PC: Colt Bradley

"He said it with such sincerity that it was really humbling in the moment," said Rojas.

Leading an affinity group can often feel like running on a never-ending treadmill of organizing event after event, where reflection takes a backseat. However, according to Rojas if she can positively affect just one person, it makes all the work worth it.

Salsa music playing over Chapel Pond, smiling faces red from the winter frost, and dancing in crampons are the mosaic of moments that make up the heart of Escala, the DC Chapter, and the New Ice Climber Weekend.

Watch Escala En Hielo Below

Climbing Grief Fund Spotlight: Gratitude

PC: Jessica Glassberg/Louder Than 11

Grief, Beauty, and Loss in the Mountains

by Hannah Provost

“When Meg climbs on the Diamond these days, she can’t seem to shake a glimpse of red in her periphery–the color of Tom’s red Patagonia R1 as he climbed with her. When she turns to catch a better look, he’s not there. Tom: her dear friend, who fed a bumblebee on a belay ledge to bring it back to life; who encouraged Meg to lead harder and harder pitches on gear; who introduced her to her husband; who she trusted more than anyone on rock. She wants to turn and see Tom’s red R1 climbing up the pitch behind her. But Tom won’t ever climb the Diamond again.

Meg Yingling is an American Mountain Guides Association (AMGA) rock guide, a lover of the high places, deeply embedded in our community—and intimately aware of the grief that haunts our sport. When she lost her friend, Tom Wright, to a climbing accident in the summer of 2020, her relationship to climbing radically changed—it mellowed and thickened and burst all at once. But thanks to the Climbing Grief Fund Grant (CGF), she was able to get the resources she needed to start processing her grief, her new relationship to climbing, and actively sit with the messiness of it all…”

Read more about Meg’s experiences with both grief and beauty in the mountains:

Climb United Feature: Finding Impact in a World of Performance

Salt Lake Area Queer Climbers (SLAQC) showing some pride at Black Rocks, St. George, UT. Land of the Pueblos and Paiute people. AAC member Bobbie Lee

A Deep Look Into the Affiliate Support Network

By Shara Zaia

Drawing on personal experience in co-creating Cruxing in Color, and the experience of affinity group leaders across the country, Shara Zaia reflects on the unpaid labor that goes into creating affinity spaces within climbing—and yet just how much it means to so many traditionally marginalized climbers to find community. Zaia uncovers the true cost and benefit of this work, and lays out why the AAC has developed the Affiliate Support Network (ASN)—our Climb United program that provides fiduciary and other administrative support to affinity groups across the country so that they can raise donations and/or become nonprofits, ultimately making their organizations more sustainable and long-lasting. Dive in to get a behind-the-scenes look at the incredible power of this work, and how the Climb United team has been determined to find impact.

Climbers of the Craggin' Classic: Ozarks

Ozarks Craggin’ Photos by Joe Kopek

We’re interviewing a climber from each event in the Craggin’ Classic Series—Rumney, New River Gorge, Devil’s Lake, Smith Rock, Shelf Road, Moab, Bishop, Ozarks—to take a deep look into the breadth of climbers that come to Craggins, and how they make the most of each unique event.

Read on to hear from climbers just like you, and their take on the things that matter to climbers.

Meet Ozarks Climber: Andrew Gamma

Scroll to read Andrew‘s Story…

Artist Spotlight: Marty Schnure & The Art of Maps

By Sierra McGivney

Photo courtesy of Marty Schnure.

In this profile of cartographer Marty Schnure, we uncover the philosophy that has influenced her creation of several beautiful maps for the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), the world-renowned AAC publication that reports the cutting-edge ascents and descents of each year. For Schnure, map-making is about blending geographical information while also evoking and displaying the relationship between that geography and whatever is important about that place to the map user—aka climbing routes, or the animal corridors of that area. Dive into this article to learn about the art of map-making, and how Schure thinks about the responsibility of a cartographer, the power of maps to express an idea, and more.

CONNECT: Inside the Life of a Climbing Photographer

Note: This episode is explicit.

In this episode, we had adventure photographer Jeremiah Watt on the pod to talk about all things climbing photography. Miah is a big fan of the AAC, and regularly donates his incredible photos to us! In this episode, Miah and the AAC’s award-winning Graphic Designer Foster Denney dive into topics like the life of a freelancer, what it takes to get the right shot on the wall, trends in climbing photography, the physical toll like jugging fixed lines to get the shot, mistakes new photogs make, and more. Ever wondered what’s going on behind the lens? Listen to this episode to get the behind the scenes life of an adventure photographer!

Resources:

Immaterial Climbing: A Story From the Catalyst Grant

Reported by Sierra McGivney

Photos by Ben Burch

Ben Burch climbing, featured in Immaterial Climbing. PC: Ashley Xu

In the backdrop of Northern Appalachia, Ben Burch (he/they) drove to nowhere. Like most high schoolers, driving was a source of relief and independence in the wake of an angsty breakup. Eventually, Burch needed to stop at a gas station, and the one they picked happened to be next to a climbing gym. Bored of driving aimlessly in their car, Burch wandered inside the climbing gym, opening the door to climbing and its community.

Burch continued cultivating their passion for climbing in Philadelphia when he went to college. There, he worked with other queer climbers to create PHLash, a community-based, peer-led group that aims to bring together LGBTQIA+ individuals to climb and socialize. Burch found he loved leading and being a part of that community. It was a space that held community and understanding in a sport that traditionally has not always provided that.

The mood shifted last year when West Virginia attempted to pass a law banning events based around queer affinity. West Virginia is only a stone's throw from Pennsylvania and hosts Homoclimbtastic, the world's largest queer-friendly climbing festival. Burch and his friends found themselves distressed about the status of Homoclimbtastic. This event, like PHLash, had enriched their climbing experience. It kept Burch climbing and invited others into the community. But now, they didn't know if it would ever exist again. Instinctively, Burch thought, I need to document this.

"I just needed to have something recorded down so people know that this event was here and that we were here," said Burch.

Their idea was to take photos from affinity groups and events they attended and post them on Instagram to exist somewhere in the ether. On a whim, Burch applied to the American Alpine Club's Catalyst Grant and was chosen. Their photos would no longer live just online but in a physical book: Immaterial Climbing: A Queer Climbing Photography Zine.

Burch embarked on an East Coast climbing adventure, photographing and memorializing queer events, meetups, and climbers.

Ultimately, the version of the bill that would outlaw Homoclimbtastic did not pass; however, the bill that did pass put restrictions on queer events. Minors are not allowed to be involved in any way in drag shows in West Virginia, and drag show organizers are responsible for checking the age of attendees. At the Homoclimbtastic Drag Show, participants had to wear a wristband and have their IDs checked.

Despite the political backdrop, the high-energy drag show and dance party at Homoclimbtastic was one of the most fun nights Burch had in years. For some photographers, when they capture moments through the pictures they take, their memories bend to how they remember them. That night, Burch took a photo of someone dancing surrounded by a bunch of people, all wearing wristbands, and titled it Armbands Around Salamander because the person dancing in the center has a salamander tattoo on their shoulder. This ended up becoming one of Burch's favorite photos in the book.

"They're really kind of lost in their moment of dance, and for me, even though it is kind of a reconstructed memory, I really think about that dance party as this moment of freedom and expression regardless of the circumstances that were trying to repress that," said Burch.

In the book, Burch focuses on his home base, too.

One moment stuck out to Burch. A participant at PHLash wearing a Brittney Spears t-shirt said that climbing in Pennsylvania is like Spears' song …Baby One More Time. The rock climbing in the northeast is generally not friendly. Outside of Philadelphia, one of the main climbing areas, Hayock, is home to Solid Triassic Diabase, a type of rock that requires precision on unforgiving edges. Philadelphia feels like a city that embeds grit and determination in its residents, much like the climbing in the area. The lyric hit me baby one more time embodies the rough climbing and the determination of the climbers in the area.

Photo by Ben Burch

Burch became interested in the idea that the city you're from—not just the culture–is reflected in the climber. In the book's PHLash section, he mixes photos from living in Philadelphia with climbing photos from the meetup.

Next, Burch changed their aperture, widened their depth of field, and traveled down to Atlanta, Georgia, to the southeast bouldering scene.

"[Bouldering in the southeast] is truly this perfect marriage of texture and shapes that force precise body positioning and control, mixed with the raw power to get through the fact that they're all just slopers disguising themselves as crimps," said Burch.

There, he participated in a meetup with the affinity group Unharnessed, an LGBT+ and allies climbing club. At this meetup, Burch was more of a wallflower; he had a couple of friends in the Atlanta area but was not a deep group member in the same way as Homoclimbtastic or PHLash. He listened in on the conversation between climbs and found it was not the idle talk that normally existed at the crag. People would talk about the climb or the person climbing, but then the conversation would shift to asking if anyone had extra food to put in the Atlanta community fridge or about the community resources near the gym. He was so struck by how focused the group was on building community through resources and knowledge.

It reminded him of a quote by bell hooks, "I think that part of what a culture of domination has done is raise that romantic relationship up as the single most important bond, when of course the single most important bond is that of community."

In their portrait section, Burch created a shallow depth of field, softening the background and pulling queer climbers to the forefront. Andrew Izzo is a crusher. He has recently sent Bro-Zone (5.14b) in the Gunks and Proper Soul (5.14a) in the New River Gorge and is a consistent double-digit boulderer based in Philadelphia. He only came out recently and is featured in Immaterial Climbing: A Queer Climbing Photography Zine. Burch thought that taking and publishing these photos of him almost served as a coming-out party. Izzo felt like there was no better way for him to come out. The intersection of being part of the queer community and part of the climbing community showed all of him. "That was a special moment in taking these photos, serving as a space for someone to embrace all of themselves," said Burch.

Everyone featured in the book's portrait section was chosen for their excellence in community work or climbing. Burch wanted to highlight these individuals who were balancing so many aspects of their identity and achieving so much within the climbing community.

The book revolves around the community Burch is most familiar with—that he could really speak to without fear of misrepresentation.

"I think all climbers are in constant chase of flow, of that feeling when you are climbing, and it feels like your body is in perfect response to what it needs to do with the rock—this immovable object that you have rehearsed and understood. For me, the East Coast Climbing Scene feels like that state of flow.

“It feels like a place where you are understood, and people know who you are, even without thinking about the larger circumstances. It's this, like, perfect moment of escape in the larger challenge of—to complete the metaphor—trying to finish the climb," said Burch.

More about Immaterial Climbing: A Queer Climbing Photography Zine and Ben Burch (he/they):

PC: Ben Burch

Burch is a photographer and climber currently based out of Washington DC. Part of queer affinity groups since they began climbing, he wanted to use this zine as a love letter to the spaces that gave him so much. For more of their photography, please follow them @benjammin_burch on Instagram.

Immaterial Climbing is a photography zine which explores the world of queer climbing. Taken over the course of 2023, this book explores meet-ups, affinity groups, and climbers who are creating their own space of belonging. The project features the event Homoclimbtastic, affinity groups Unharnessed and Phlash, as well as portraits of queer climbers. It is a lovely coffee table book, a book to add to your gym's collection, or a reminder that we'll always be here. Grab your copy.

This project was made possible through the American Alpine Club and the bravery of the queer climbing community.

CONNECT: Mo Beck on the Impact of Adaptive Climbing Fest, and Retiring from Competitions

Adaptive Climbing Festival (ACF) is crafting a shift in adaptive climbing. Not only is it easier than ever for a person with a disability to TRY paraclimbing, but through ACF, there are also now more opportunities to build skills and depth in the paraclimbing community, deepening the knowledge and expertise that adaptive leaders can use to empower future generations of adaptive climbers.

We sat down with Mo Beck, one of the organizers of ACF and a pro athlete, to talk about how Adaptive Climbing Fest started, its impact, and why ACF is such a meaningful finalist for the AAC’s Changemaker Award. We also chatted about Mo’s climbing philosophy, the emotions of retiring from competing, trolls on Mountain Project, and how she’s seen the sport change over 25 years of climbing.