Provided by Michael Levy

A story from the AAC Library

By: Sierra McGivney

Jean Crenshaw and Helen Kilness rode their motorcycle away from the US Coast Guard base in Georgia in 1946. They had just taught themselves how to ride the motorcycle in the bike dealership's parking lot. The two had become fast friends working as Radio Operators in the Coast Guard. With the war over, they were untethered, the future and road ahead of them. Both grew up out west, so they headed that way, the wind roaring around them.

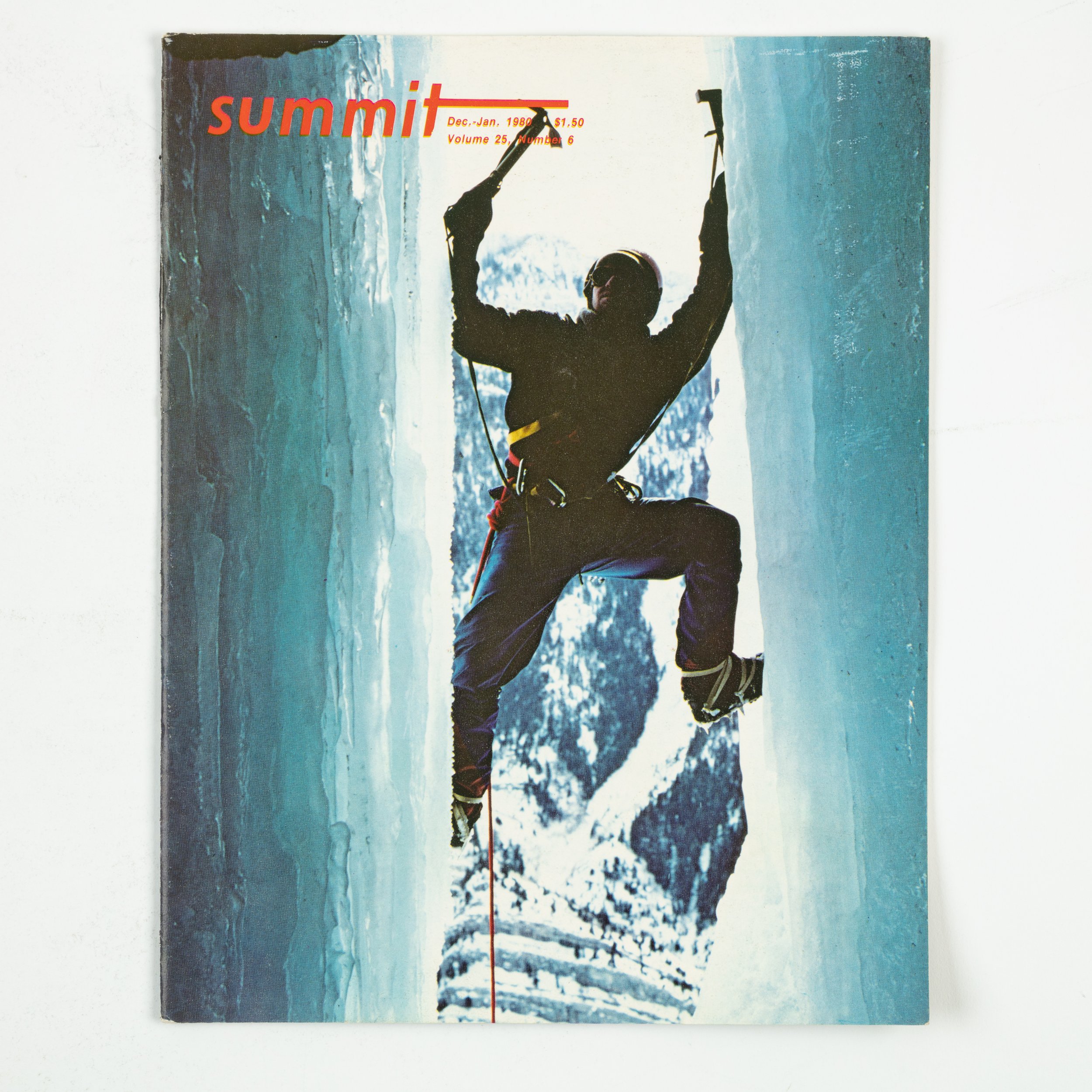

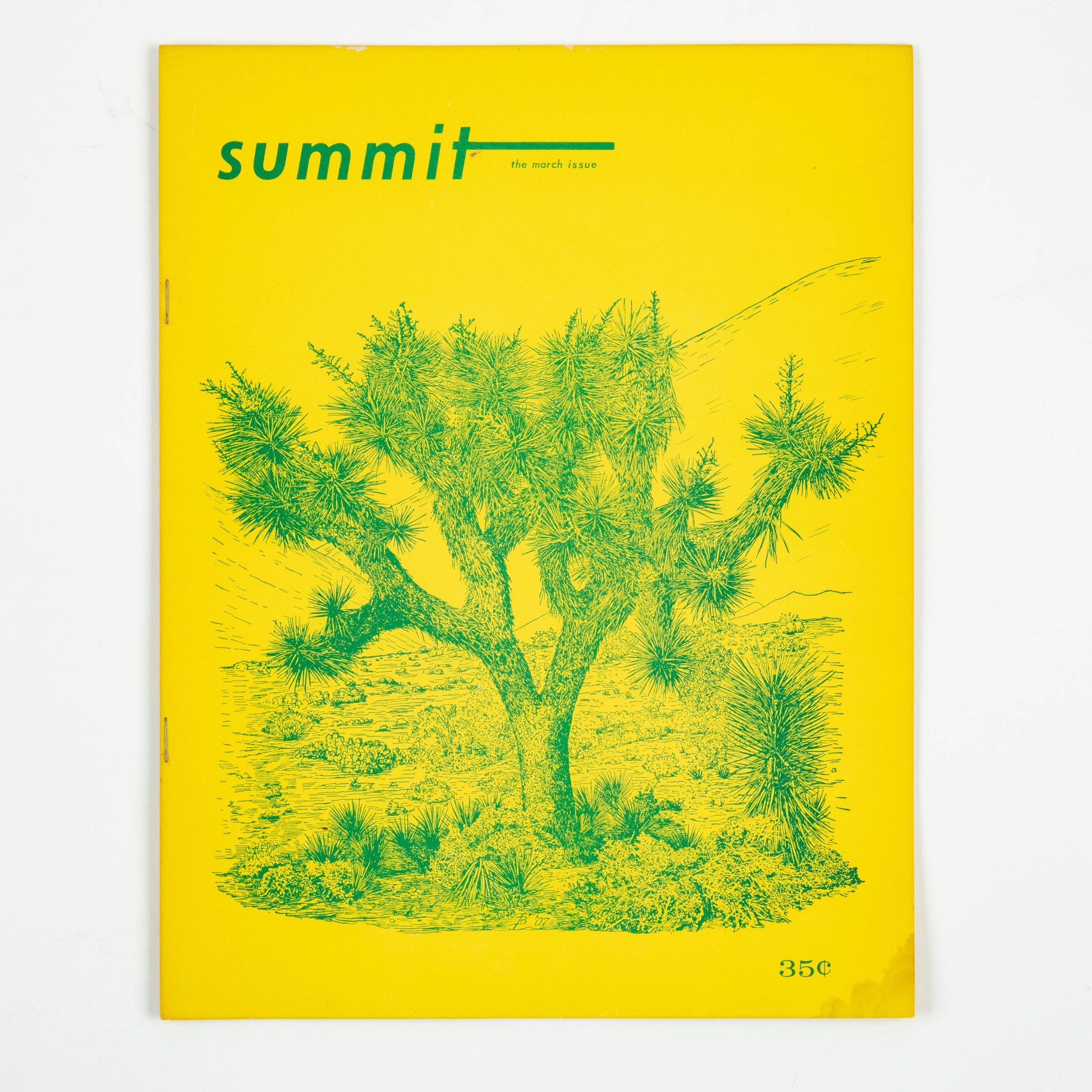

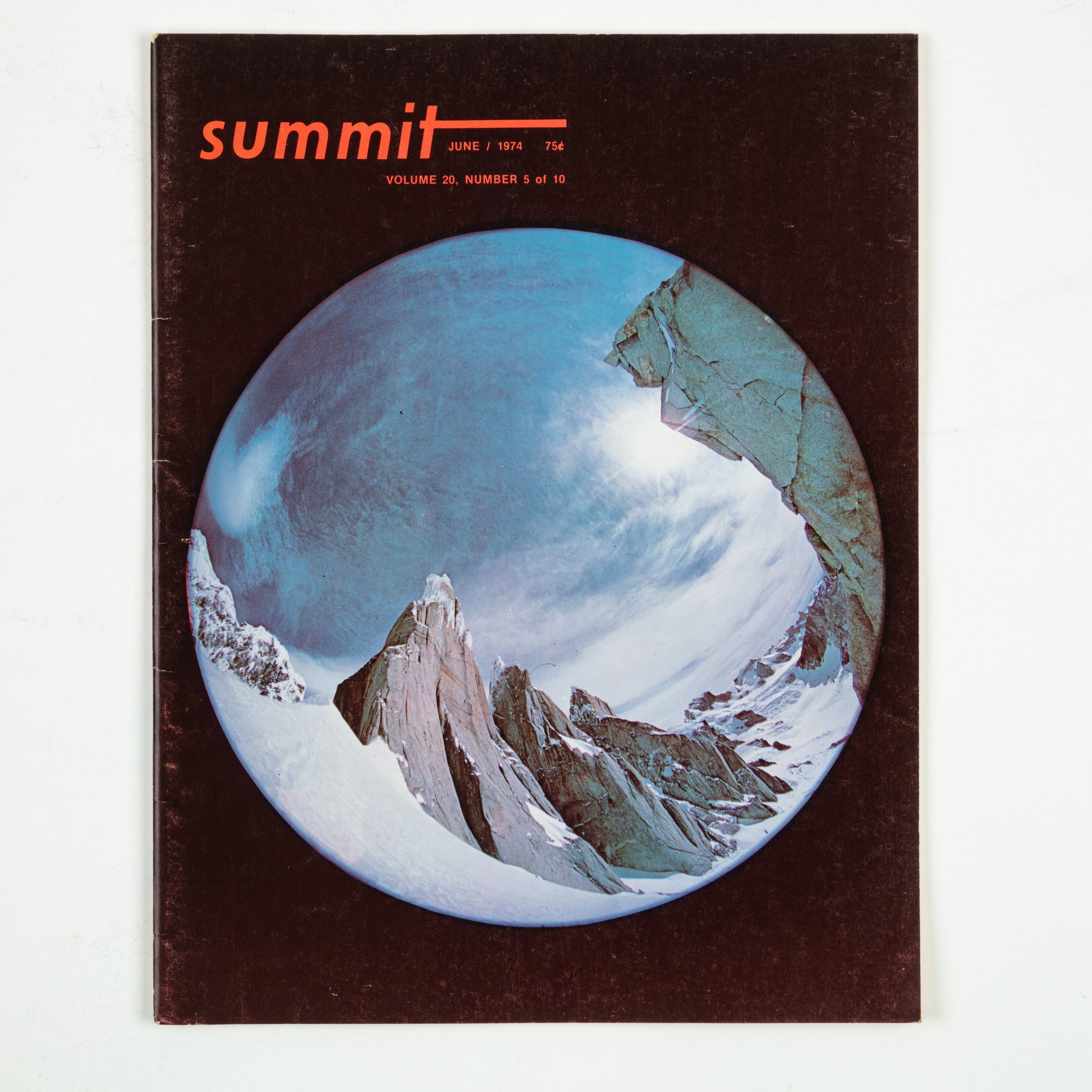

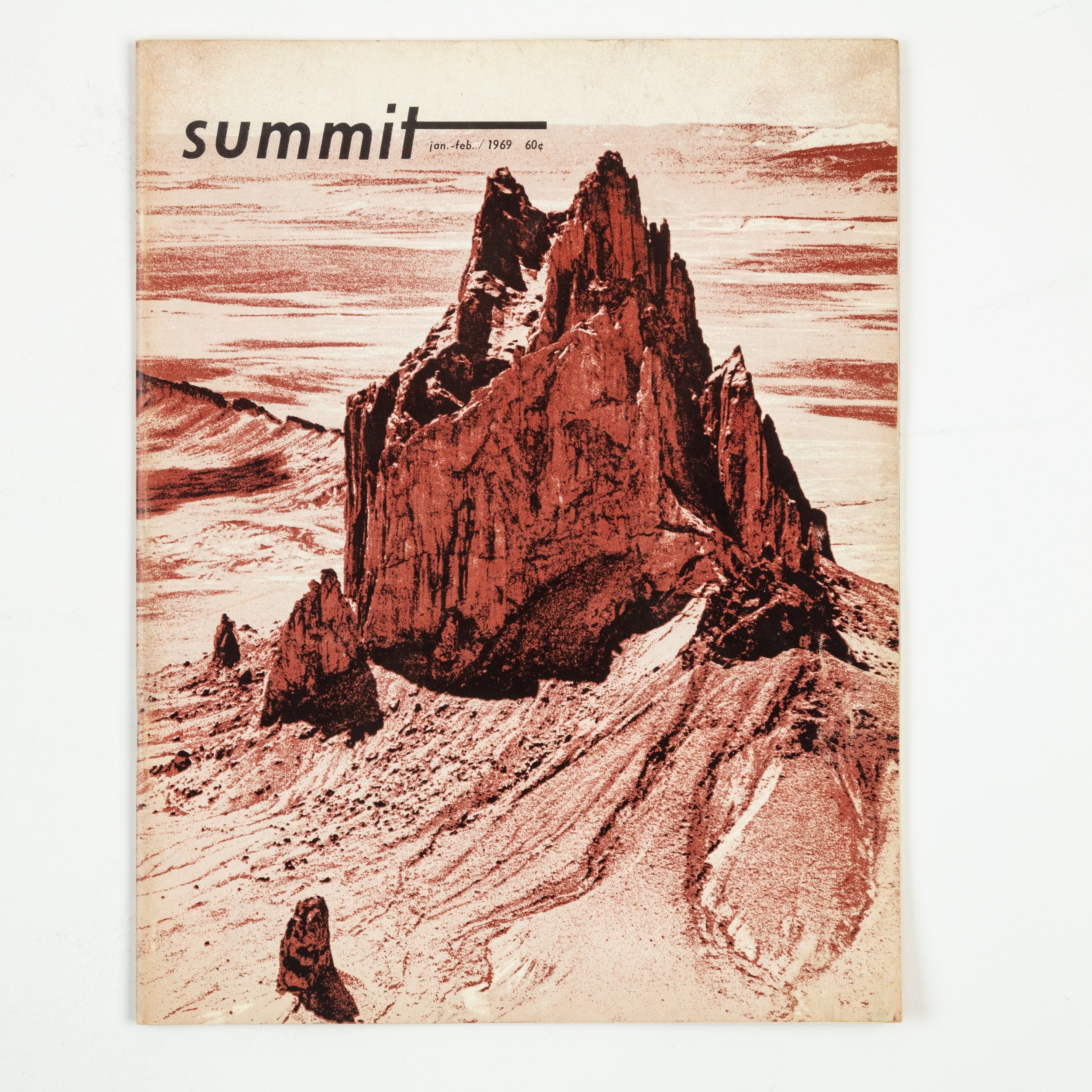

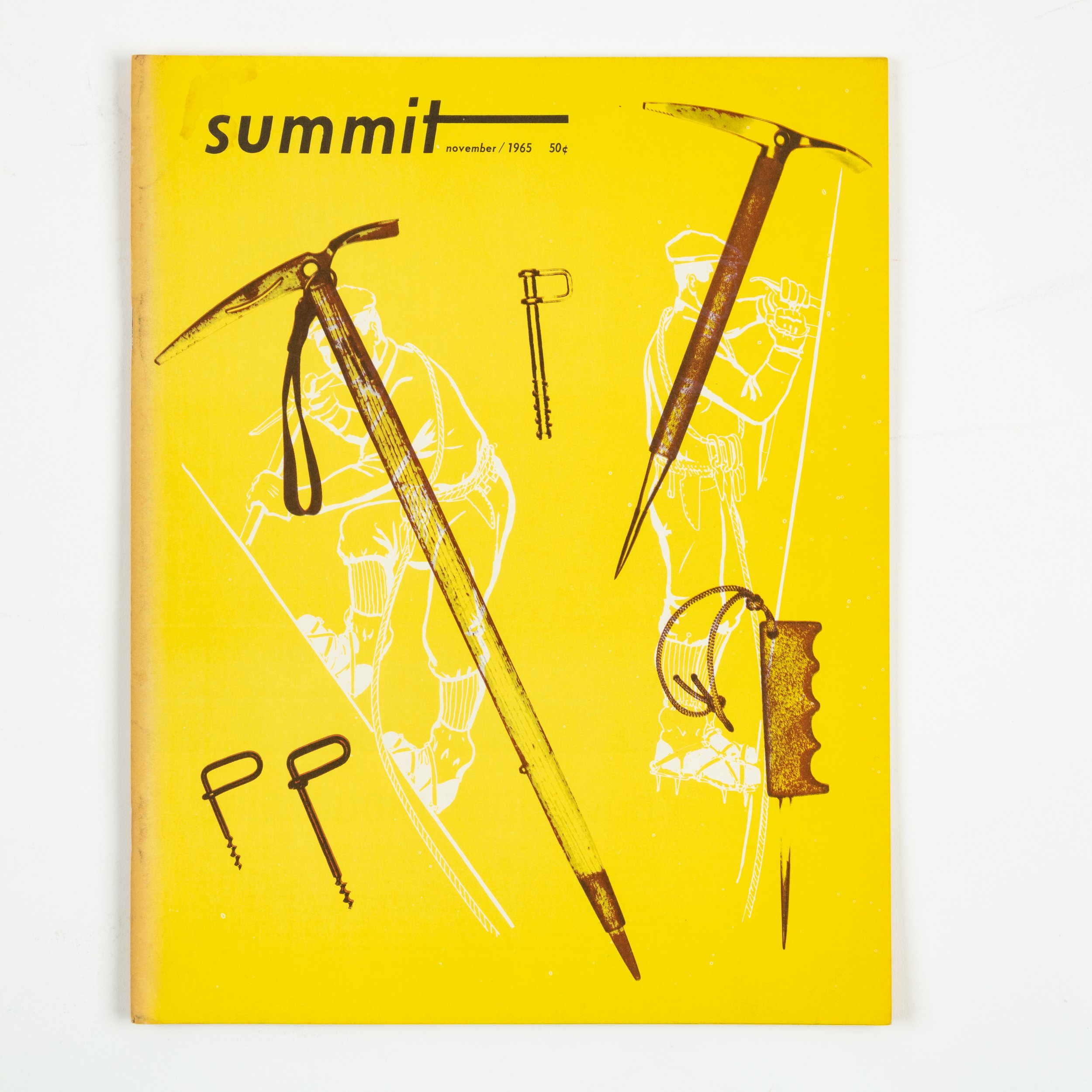

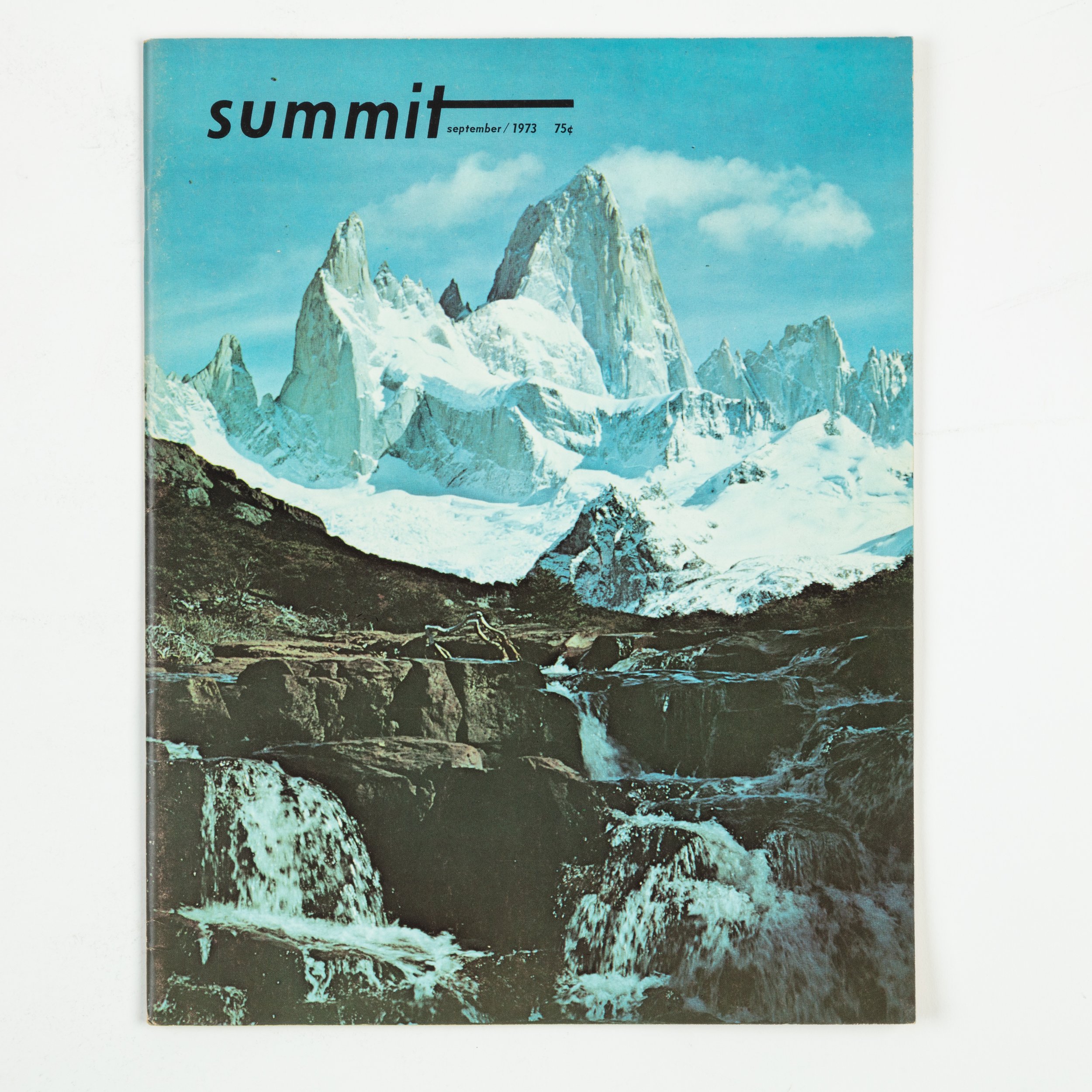

Once in California, they worked in the publishing and editing industry, and on the weekends, they went out on trips with the Sierra Club. The two fell in love with rock climbing and playing outside. They were completely inseparable. With time they moved to Big Bear, CA, to an old Forest Service cabin. They wove their two favorite things together and started a climbing magazine, the first of its kind, in 1955.

Summit Magazine was edited, published, and produced in Crenshaw and Kilness's house. The basement contained a dark room for photo and print development.

The two were some of the original dirtbags. They would make enough money and write enough content for the magazine and then run away into the mountains and play. Their first magazine cost 25 cents.

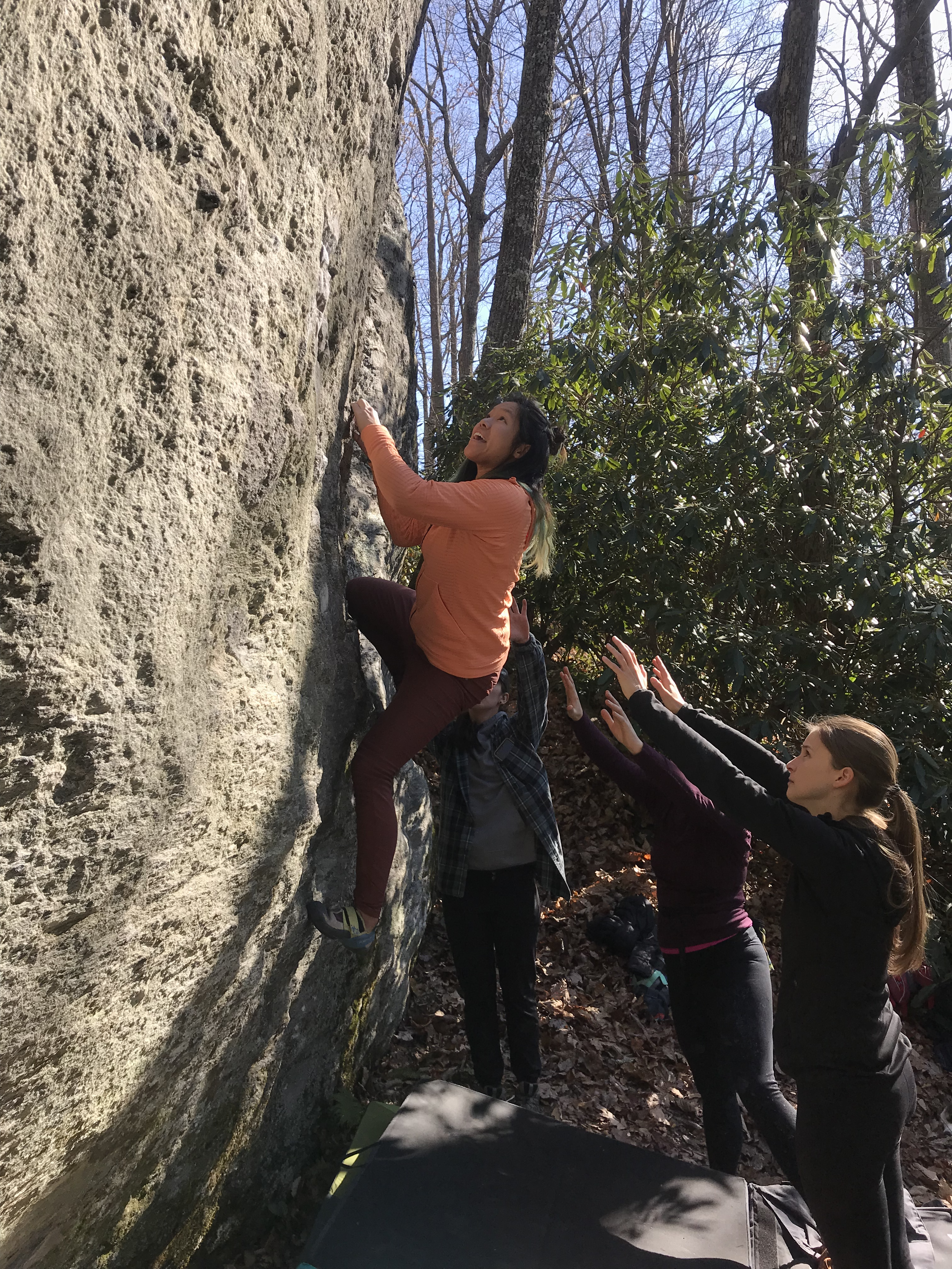

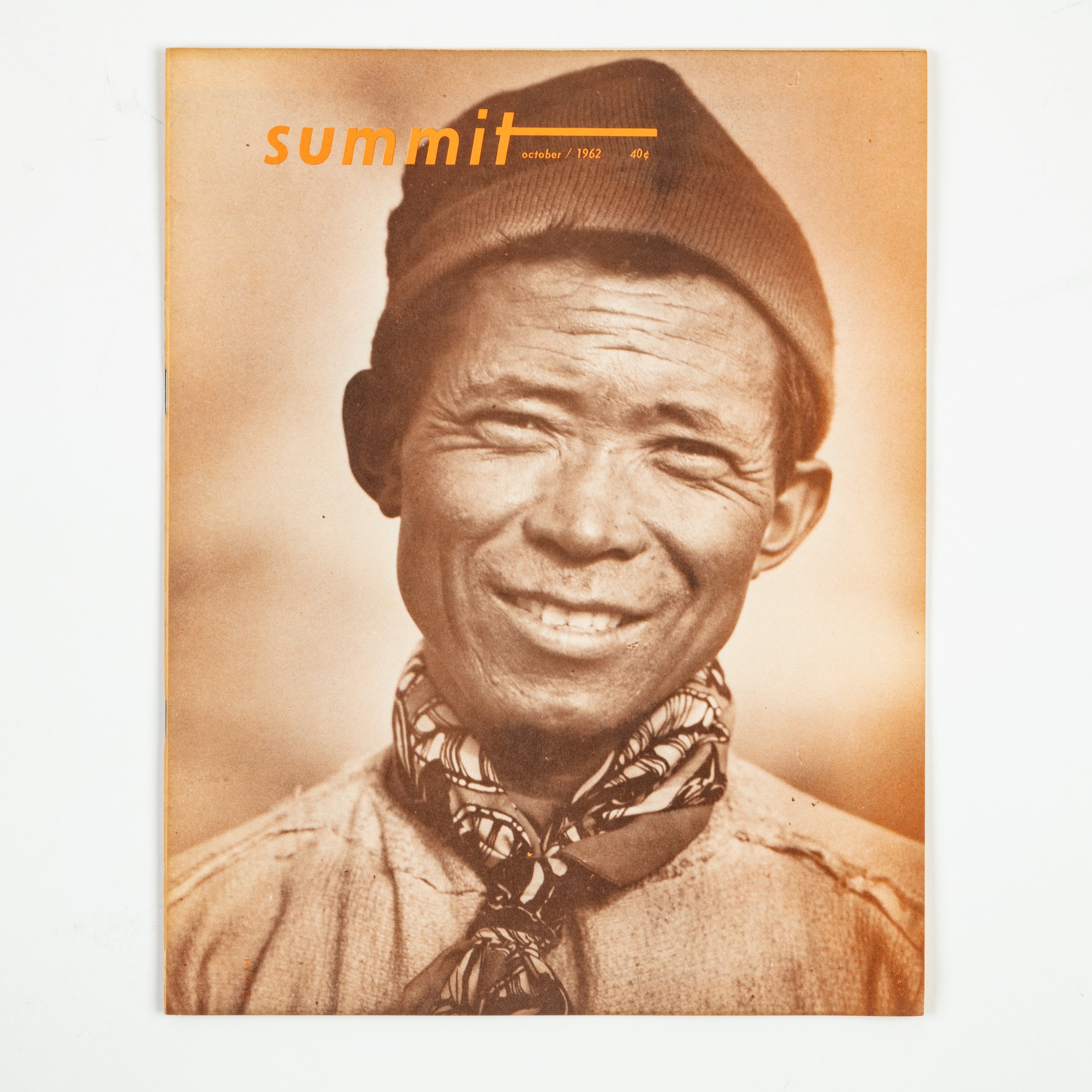

In the post-WWII climate of the United States, they went against the grain. Though not against marriage or children, Kilness and Crenshaw were committed to expanding and redefining the purview of women. Alongside the complexities of their religious commitments and their vision for climbing journalism, they were also two women who wanted to throw out the kitchen sink and replace it with summits.

Provided by Michael Levy

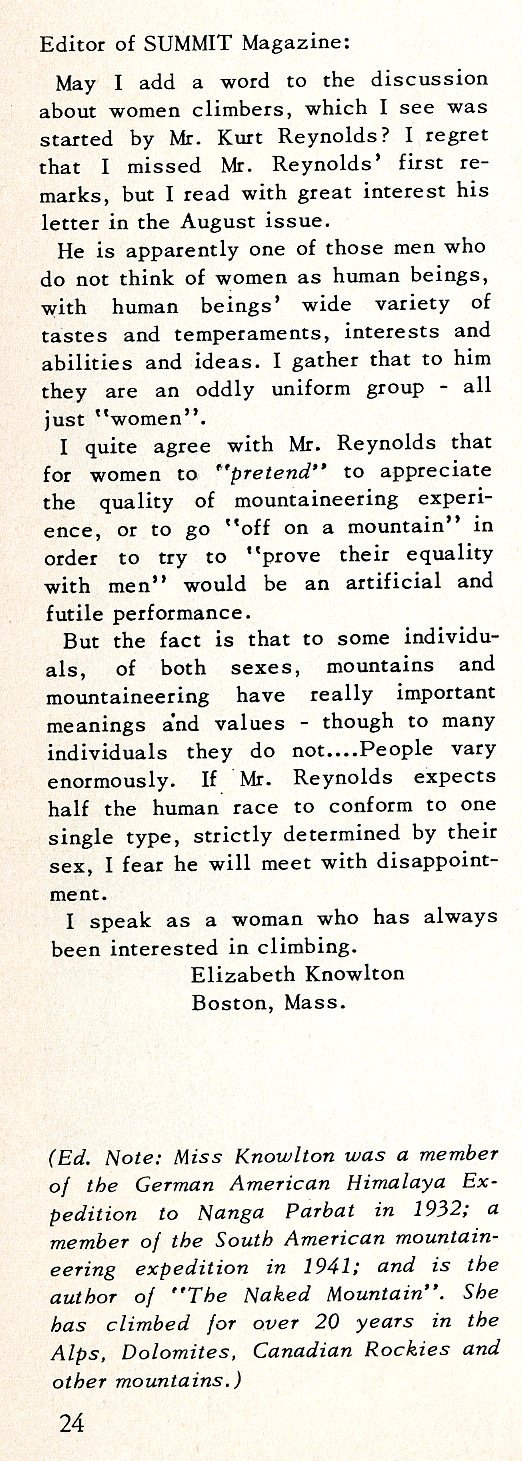

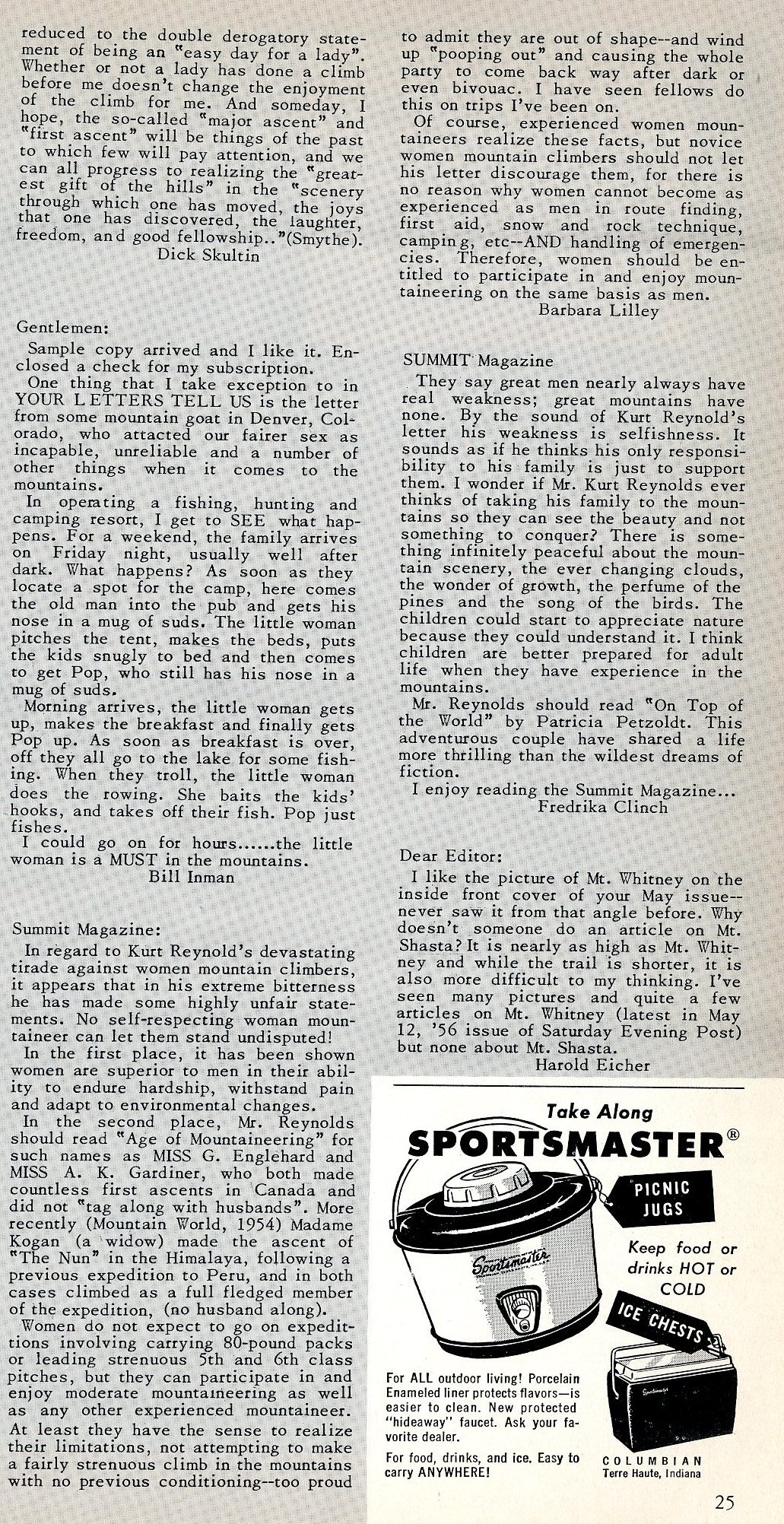

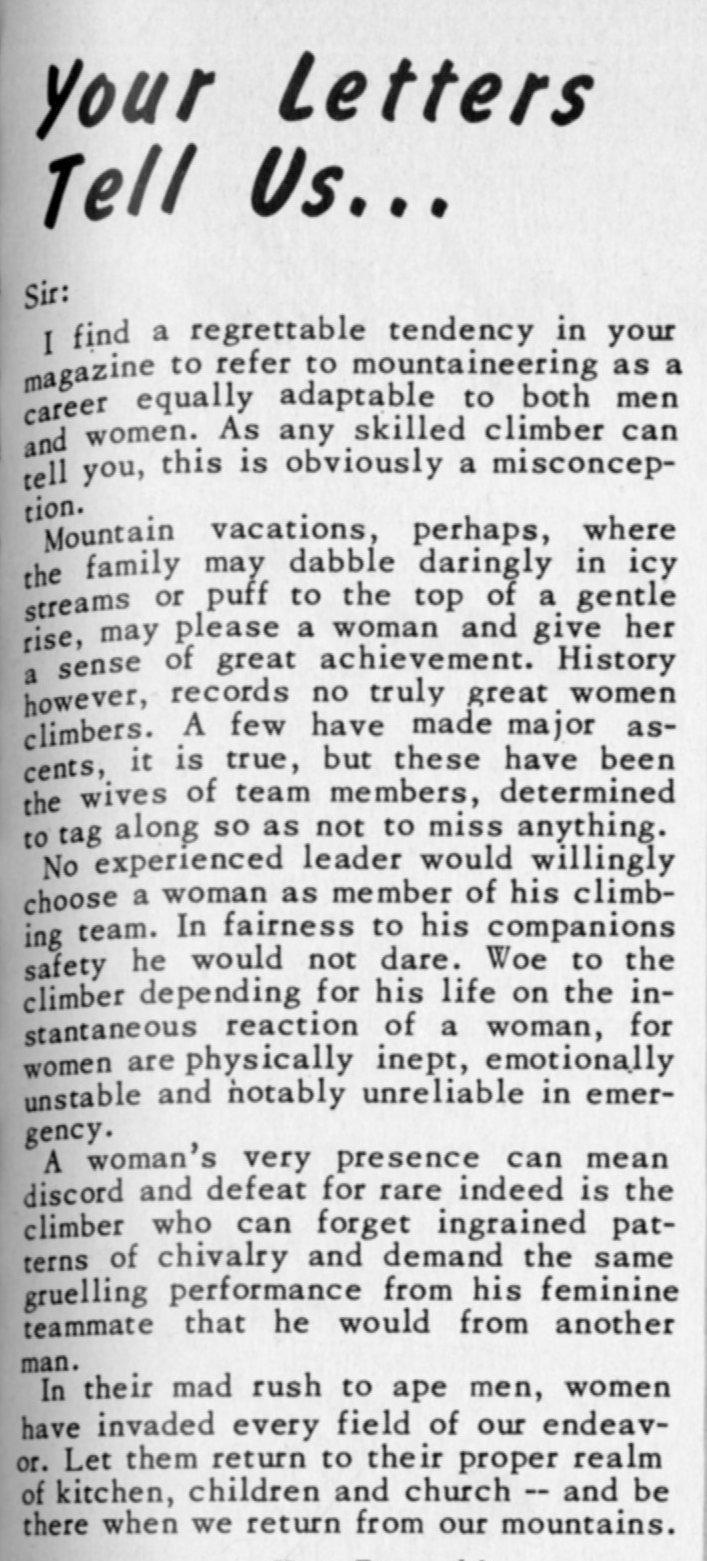

Kilness and Crenshaw avoided letting it be known that they were women on the masthead of Summit Magazine. Jean became Jene, and Helen became H.V.J Kilness. Because of this, some men felt free to write letters to the editor, denigrating women. In response, Kilness and Crenshaw would publish these letters and those that would follow, opposing these sexist views. The comments section of Summit Magazine was like the Mountain Project forum of the 1950-70s.

Kurt Reynolds from Denver, Colorado, wrote, "A women's very presence can mean discord and defeat, for rare indeed is the climber who can forget ingrained patterns of chivalry and demand the same grueling performance from feminine teammates that he would from another man. In their mad rush to ape men, women have invaded every field of our endeavor. Let them return to their proper realm of kitchen, children, and church–and be there when we return from the mountains."

The comments section regulated itself, and both men and women expressed their views against this comment.

Elizabeth Knowlton, a famous mountaineer, countered, "But the fact is that to some individuals, of both sexes, mountains, and mountaineering have really important meanings and values—though to many individuals they do not … People vary enormously. If Mr. Reynolds expects half the human race to conform to one single type, strictly determined by their sex, I fear he will meet with disappointment. I speak as a woman who has always been interested in climbing."

Others said in defense of women, "Mr. Kurt Reynolds rather sickened my stomach with his opinions on the female of the human species. I'm sure that no registered nurse would appreciate his statement on women being 'emotionally unstable and notably unreliable in an emergency,'" responded Dick Skultin.

Kilness and Crenshaw probably laughed whenever they received letters addressed "Dear Sir" containing sexist views of the day. Little did the men writing in know that two mountain climbing women ran Summit Magazine.

Instead of outright confronting these individuals, they proved them wrong through every magazine they produced that empowered women.

Provided by Michael Levy

The letters to the editor weren't the only place these nuanced subjects were brought up. In the fictional story "The Lassie and the Gillikin" from the June 1956 edition of the magazine, the author writes about the undertones of sexism in climbing at the time and the expectation for a woman to make herself smaller. In the story, a male climber takes Jenny climbing for the first time. She starts with beginner climbs and every weekend works to climb harder. She persists and becomes better. At one point, when Jenny succeeds on a climb, the male climber does not, and he is suddenly cold towards Jenny. This male climber has lunch with another woman when he usually eats with Jenny. He weaponizes this woman to show Jenny further how much he distastes her success.

Provided by Michael Levy

The Gilikin, a little creature that climbers blame for tangled ropes or slick holds, suggests to Jenny that he push her off a climb to make the male climber interested in her again. Jenny agrees, and after she falls off a climb, his interest in her returns, underscoring the writer's point.

Jane Collard said it best in the July 1956 comments section of Summit: "Men need to feel superior to women, especially in outdoor, rugged, manly-type activities, and a woman mountain climber is liable to give 98% of the male population an inferiority complex because there are so few men who are mountain climbers and also society says mountain climbing isn't feminine."

The richness of Summit was that it was a proving ground for these kinds of hard conversations about equity, but the editors also insisted on doing so playfully.

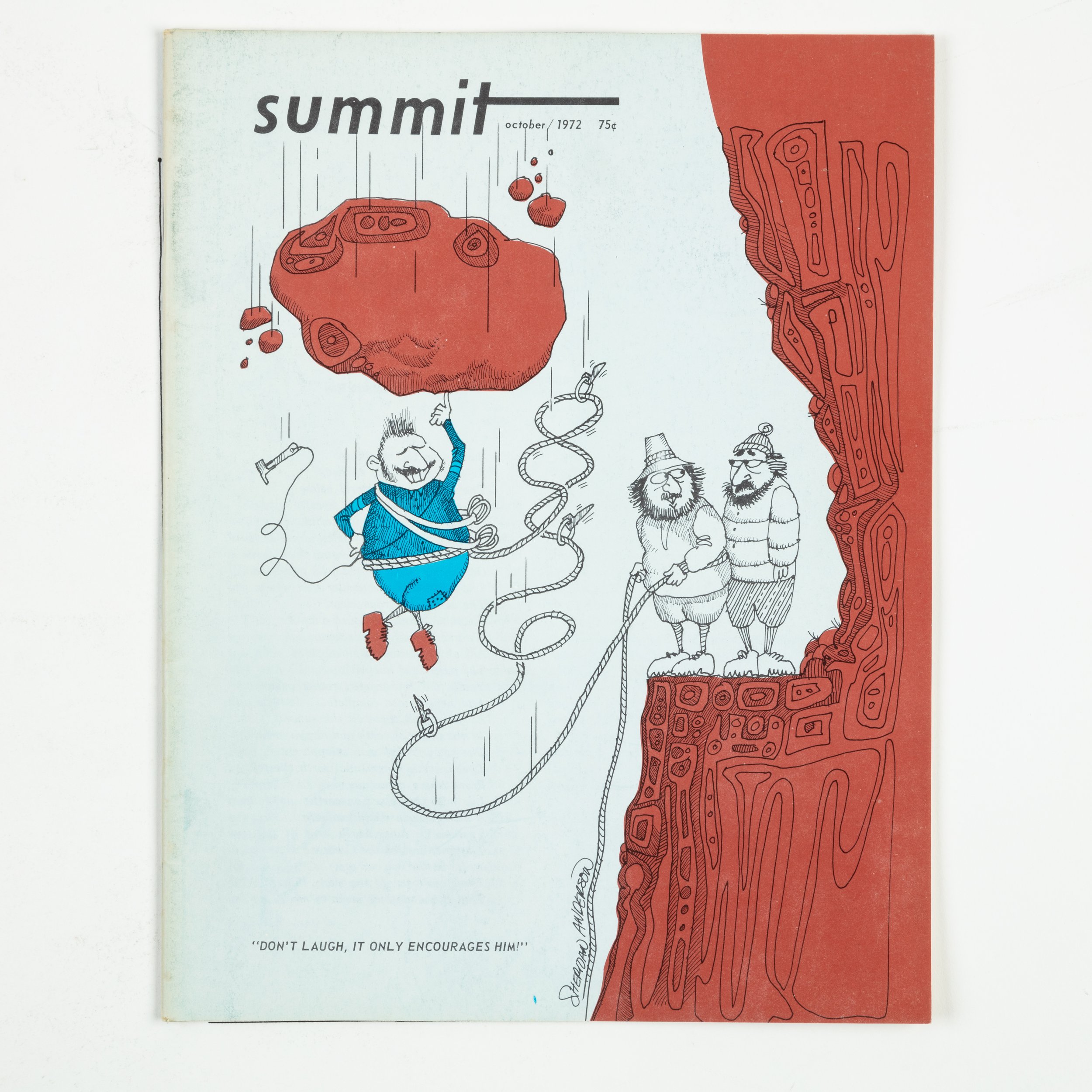

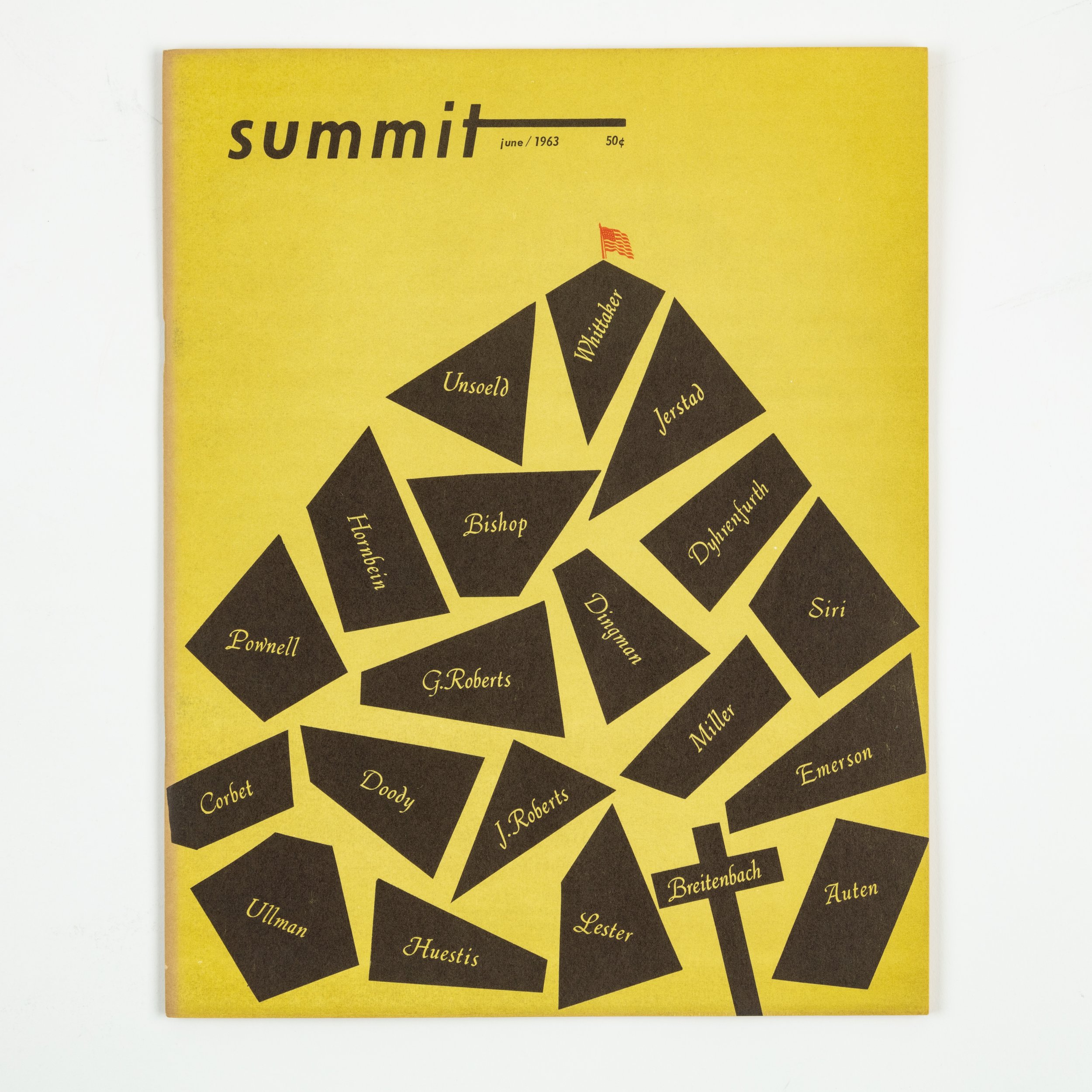

Flipping through old Summit Magazines, you'll find various cartoons and articles. A person skiing off El Capitan is on the cover of their March 1972 issue. The cover was made to look real with a photo of El Cap and a drawing of a small person with a red parachute skiing off of it. On the inside of the magazine, a complete description: "In a well planned and skillful maneuver, Rick Sylvester skied off the top of El Capitan in Yosemite National Park at approximately 50 mph, then parachuted to the valley floor." You can tell that Kilness and Crenshaw were having fun. They didn't take themselves too seriously.

Oddly enough, an ad for Vasque boots is placed on the outside cover. The ad says, "Vasque…tough books built by men who've been there…Vasque the mountain man boot."

Provided by Michael Levy

The articles in Summit had an extensive range of topics, from challenging technical climbs to backpacking and ecology. The magazine had a news section called "Scree and Talus" which always included a poem. One addition of "Scree" includes a granola recipe next to the information about an unclimbed mountain in Nepal called Gauri Shankar.

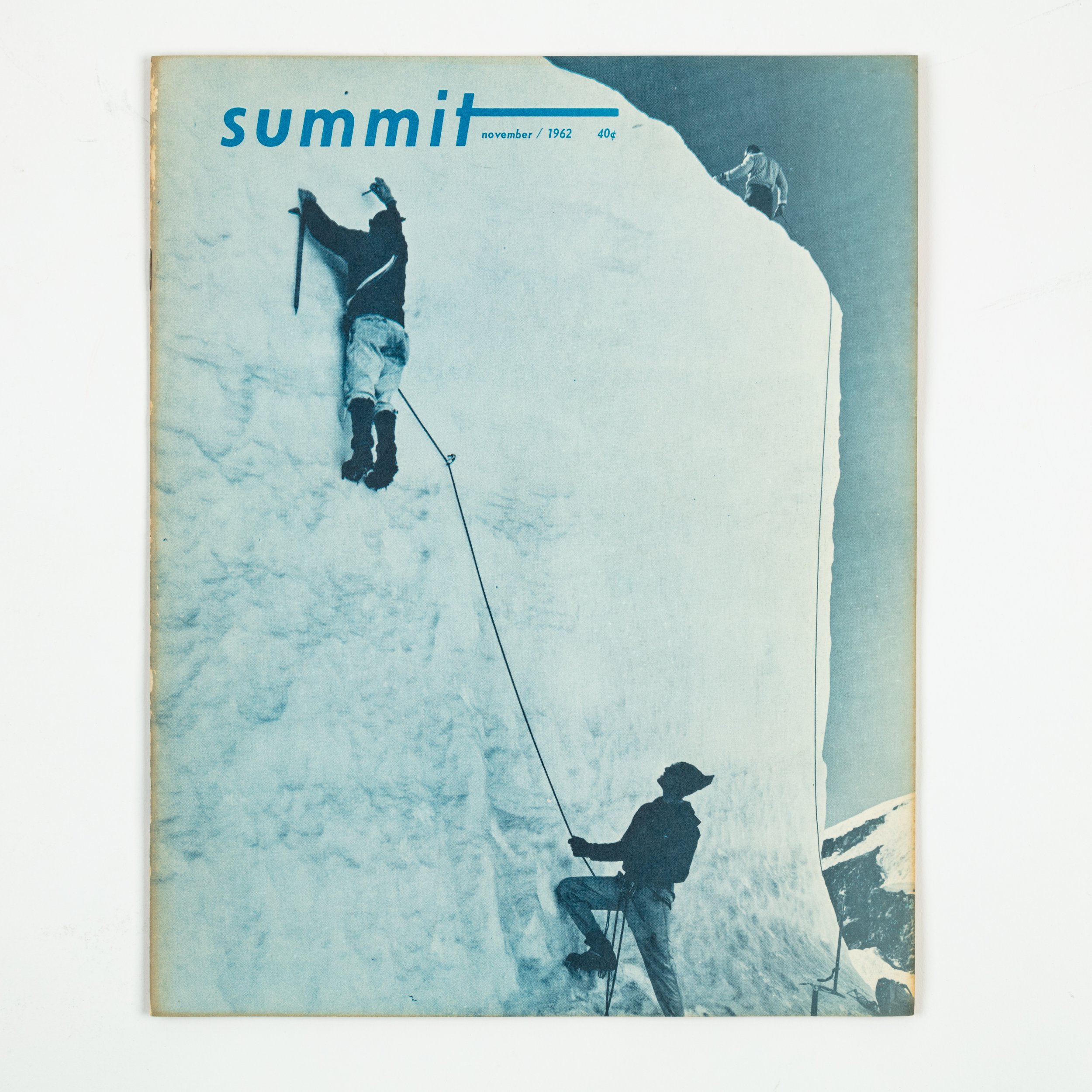

The swirly fonts, playful cartoons, and various article topics blended feminine elements into an otherwise 'masculine' sport for its time. Kilness and Crenshaw were redefining climbing to include their vision—broadening and deepening what climbing could mean and who climbing was for.

Summit was about all aspects of climbing, not just climbing difficult grades and training, which are worthwhile stories to tell but do not encompass the soul of climbing, the why of climbing. Summit Magazine was about pursuing the outdoors and having fun while doing it. Summit's depth and earnest silliness came from Kilness and Crenshaw's ability to take a step back from climbing, see their complex role in it, and in turn, climbing's role in life. That philosophical distance certainly takes the edge off the grade-chasing.

When magazines like Rock and Ice (1986) and Climbing (1970) came onto the scene, Summit fell off. Kilness and Crenshaw themselves ascribed this to their competitors' editorial focus on sending hard and putting up new technical routes. But whether cutting-edge climbing simply sells better or it was the usual story of big media winning by sheer resources, the project was no longer sustainable. Killness and Crenshaw sold the company in 1989, the same year the American Alpine Club recognized their contribution and lifetime service to the climbing community. Under new owners, Summit continued until 1996, after which it was discontinued.

You can still be transported to 1974 and look at old photos of beautiful landscapes worldwide. The AAC library holds all issues of Summit Magazine from 1955-1996. These magazines can be an excellent resource for planning trips or a looking glass into a past era of climbing.

Provided by Michael Levy

And Summit's journey continues. Through long-form print media, Summit Journal will be produced twice a year in large format to preserve the richness of climbing storytelling. In a world of clickbait articles, Summit is daring to produce quality climbing journalism and once again encompass the soul of climbing. Hopefully, they can capture Kilness and Crenshaw's playful essence even if someone isn't skiing off El Capitan on the cover. Returning to climbing journalism's roots just might take us to new places.