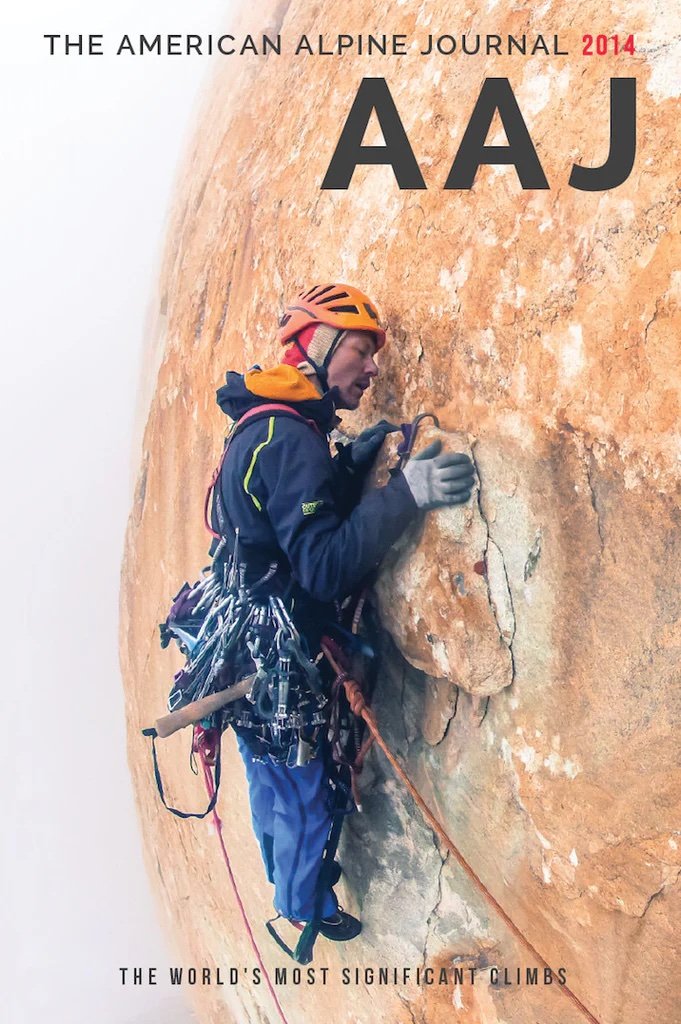

Read how a professor of mechanical engineering at Seattle University solved a geographic mystery in Uzbekistan and made the first known ascent of that nation’s highest peak. (This same peak was also No. 141 in the professor’s quest to summit the high point of every country in the world.) Plus: attempting Everest, climbing Kangchenjunga, completing the “Seven ’Stans,” and becoming a Snow Leopard—just a few recent accomplishments in the very busy life of Eric Gilbertson.

Nearing the summit of Alpomish. Photo: Eric Gilbertson.

The following is adapted from a report by Eric Gilbertson for AAJ 2024.

Alpomish:

The First Ascent

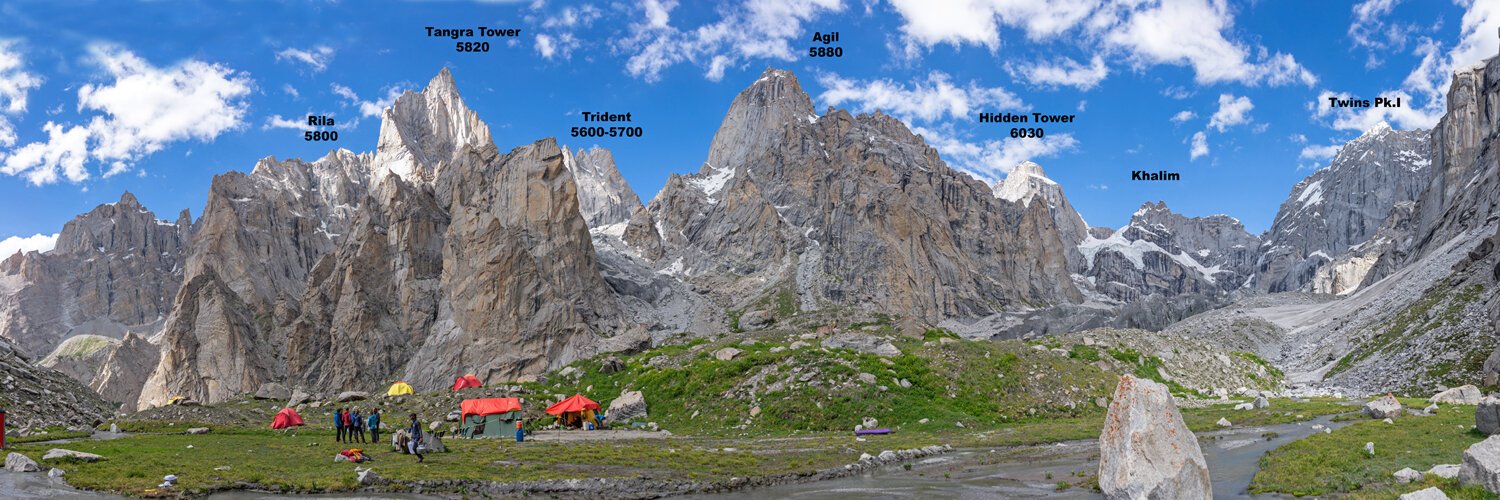

Until recently, it was widely accepted that a broad, rocky 4,643-meter mountain in the Gissar Range, on the Uzbekistan-Tajikistan border, was the highest peak in Uzbekistan. This was based on the 1981 Soviet topographic map, the most accurate and recent map of the area. (In recent times, some online sources have called this mountain Khazret Sultan, but this is incorrect.) While researching Peak 4,643, possibly first climbed by Soviets in the 1960s, I realized that a border peak about six kilometers to the south, known as Alpomish, was potentially taller than Peak 4,643. Andreas Frydensberg (Denmark) and I laid plans to carry a differential GPS unit and sight levels to both summits and determine which was higher.

Acclimatized from ascents of Pik Korzhenevsky (7,105m) and Pik Ismoil Somoni (Pik Communism, 7,495m) in Tajikistan, Andreas and I headed to the Uzbekistan border region, and on August 21 we started our approach from Sarytag village. We hiked southwest alongside the Dikondara River, cached a few days of food, and continued south over several glaciated 4,000-meter passes and many talus fields, around 23 kilometers in total. Our base camp was by an unnamed glacier below the steep east face of Alpomish.

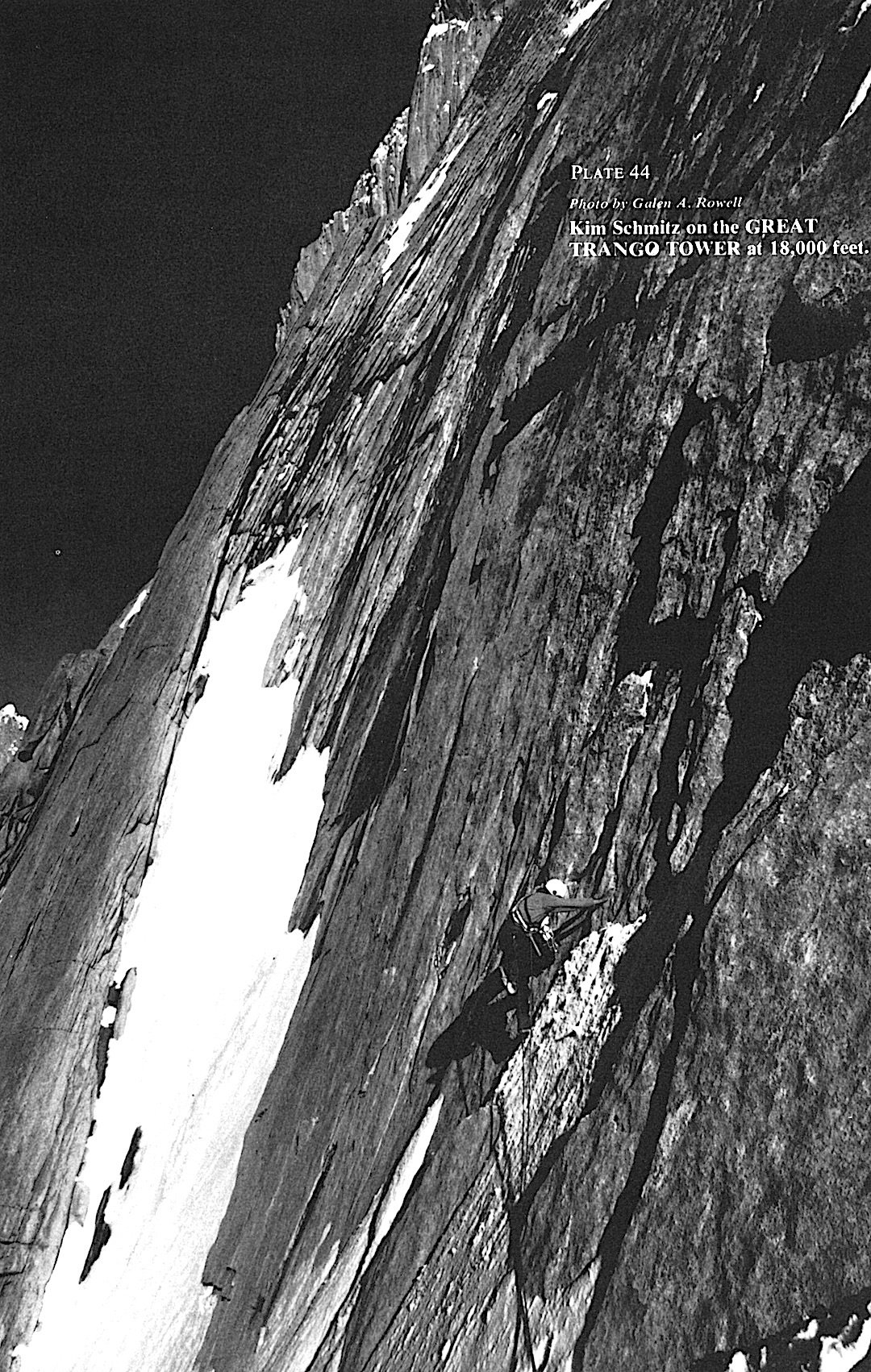

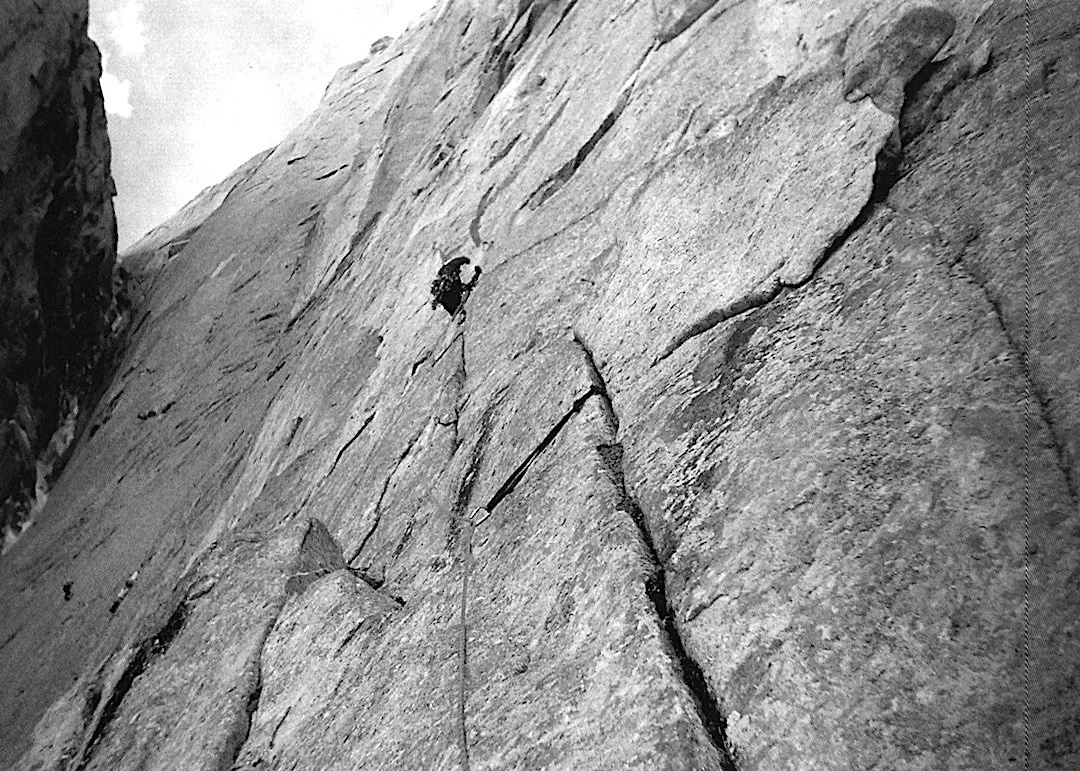

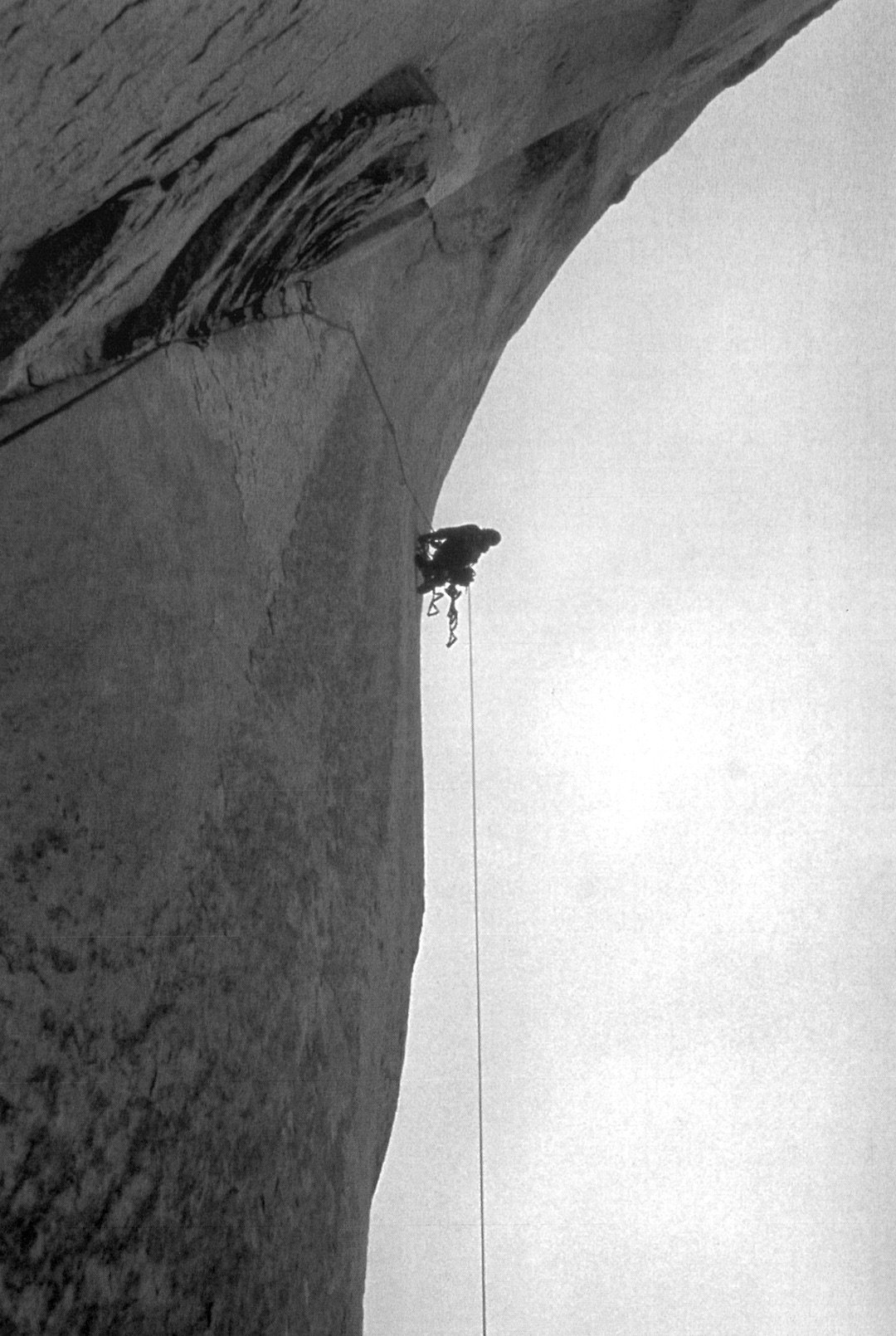

The first known ascent of Alpomish, by the east face (5.8). The rock wall is about 400 meters high. Photo: Eric Gilbertson.

The four-spired peak loomed above camp with 400-meter granite faces on each spire. The southernmost spire looked to be the tallest, which I verified with sight levels.

On August 23, we hiked to the east face and scrambled up a big gully on scree until it was blocked by a huge chockstone. I led a rock face then traversed left delicately to reach the top of the chockstone. Above a waterfall in the gully, ice continued all the way up to the notch, and since we’d left our ice gear below, we climbed the rock wall and ridge crest to the left. Once on the gendarmed summit ridge, a final knife-edge brought us to the top.

Using the sight levels, I first verified that all the nearby spires of the peak were shorter—we were definitely on the highest point of Alpomish. I set up the differential GPS, but it had trouble acquiring satellites. So I pointed my sight levels toward Peak 4,643, and with each level measured 10min–20min angular declination looking down at the distant summit. Clearly it was lower. There were no anchors, cairns, or any sign of human passage anywhere on Alpomish, so it seemed very likely we had made the first ascent. Our measurements showed that Alpomish is 25 meters (+/-8 meters) higher than Peak 4,643, giving an elevation for Alpomish of around 4,668 meters.

Gilbertson and Frydensberg on the summit of Alpomish. Photo: Eric Gilbertson.

After rappelling and downclimbing, we staggered back into camp shortly before midnight. Our route was the Upper East Face (300m, 5.8).

To be absolutely certain about the relative elevations, I wanted to take measurements from the top of Peak 4,643, looking back to Alpomish, so the next day we retraced our route over the glaciated passes, picked up our food cache, and hiked to the base of Peak 4,643.

On August 25, we climbed the northeast ridge, with long stretches of 4th-class scrambling on a knife-edge and two pitches of 5.7. On the summit, I used sight levels to measure the angular inclination up to Alpomish. All six measurements showed that Alpomish is higher than Peak 4,643, making it the highest point in Uzbekistan.

Andreas Frydensberg on top of Noshaq, the 7,492-meter high point of Afghanistan, in July 2019, two years before the Taliban takeover of the country. Photo: Eric Gilbertson.

The Seven ’Stans

Breaking trail up massive Pobeda, the highest summit in Kyrgyzstan. Photo: Eric Gilbertson.

Eric Gilbertson and Andreas Frydensberg’s climb of Alpomish was part of a four-year effort to reach the highest point of all seven nations whose names end with “stan.” Most of these were very challenging mountaineering objectives.

In 2019, they climbed Noshaq (7,492m, Afghanistan). In 2021, they tagged the summits of Khan Tengri (7,010m, Kazakhstan) and Pobeda (7,439m, Kyrgyzstan). In 2022, it was K2 (8,611m, Pakistan), without supplementary oxygen. And in 2023 they climbed Ismoil Somoni (7,495m, Tajikistan), Ayrybaba (3,139m, Turkmenistan), and Alpomish (ca 4,668m, Uzbekistan). Gilbertson reported that Pobeda (via the Abalakov Route) was technically and physically the most difficult of the seven (technical climbing at high altitude with no fixed ropes, deep snow, serious objective and frostbite danger) and that Noshaq was logistically the toughest (landmines and kidnapping hazards).

EVEREST & KANGCHENJUNGA

As if climbing two 7,000-meter peaks in Asia last summer weren’t enough, Eric Gilbertson also made a strong attempt on Everest in May (reaching 8,500 meters without supplementary oxygen or personal Sherpa support). He then flew to Kangchenjunga and summited the world’s third-highest peak, thus ticking the high point of India on his list.

Gilbertson, along with his twin brother, Matthew, ultimately hope to reach the high point of every country in the world, a project that started in 2010. As of this month, Eric has climbed 143 of 196 the world’s high points. See the Country Highpoints website for his extensive trip reports.

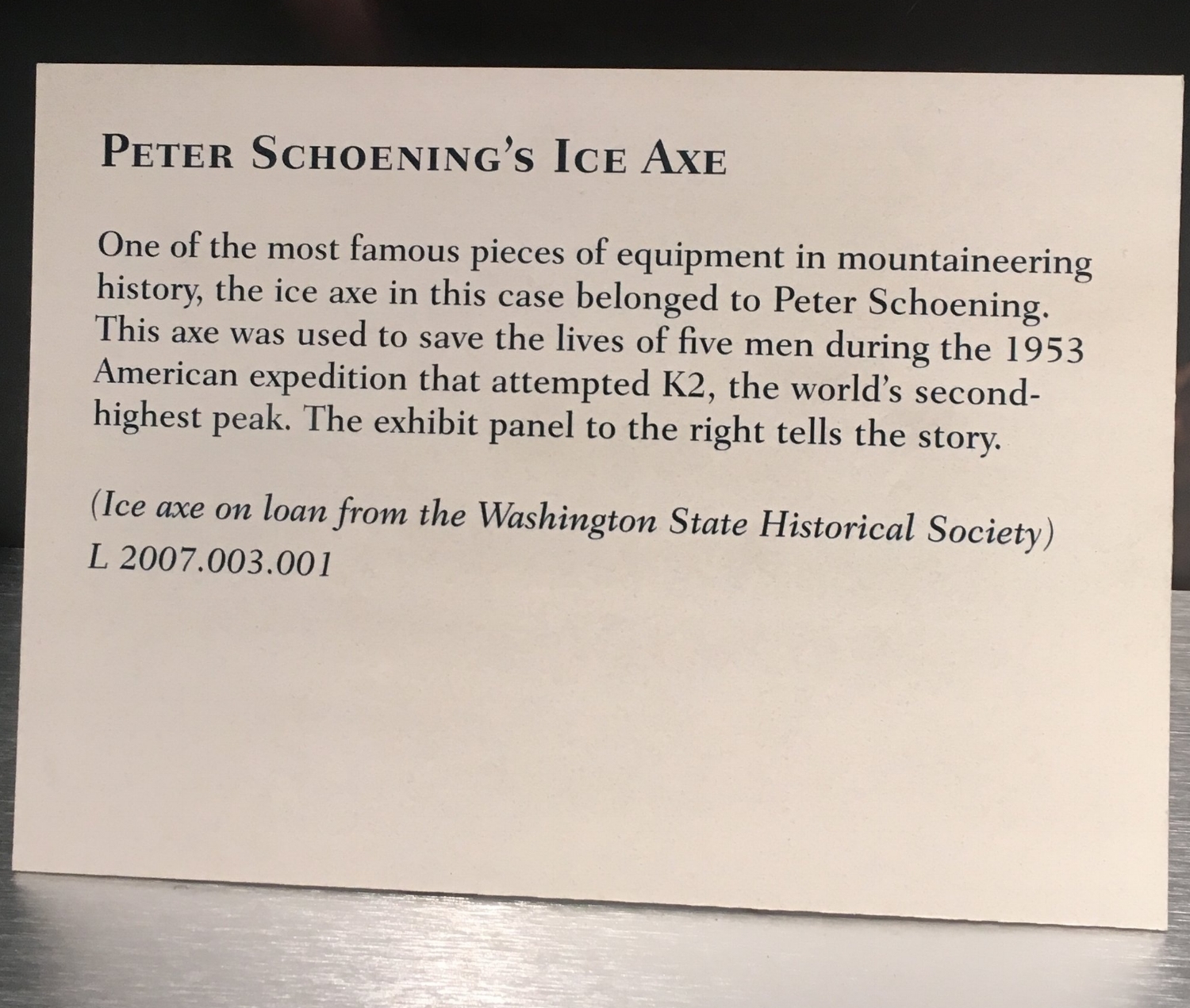

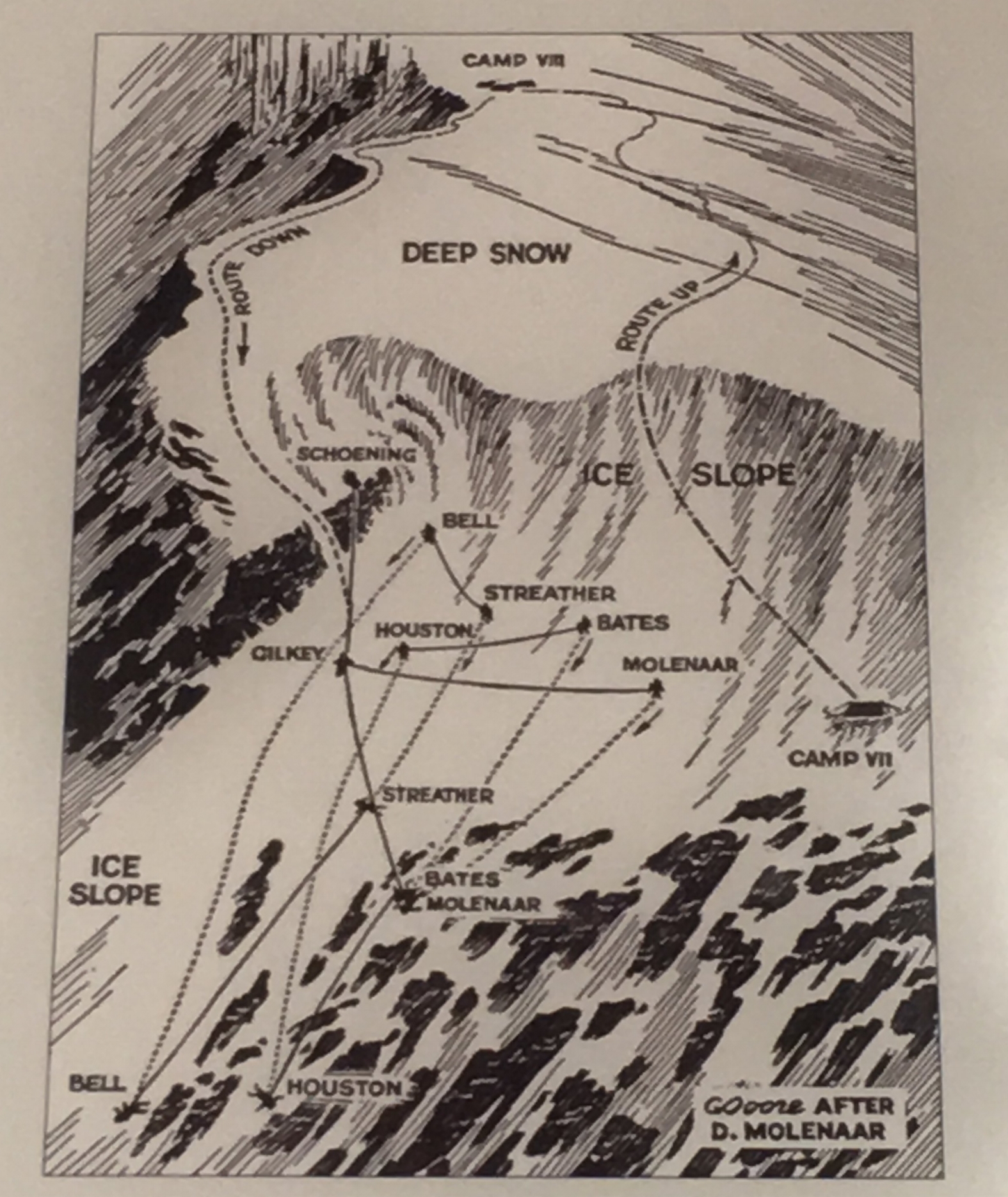

Having climbed the five 7,000-meter peaks of the former Soviet Union, Gilbertson and Frydensberg applied to be named Snow Leopards, a great honor of Russian mountaineering. In November 2023, Gilbertson became the third American Snow Leopard (after William Garner and Randy Starrett in 1985) and Frydensberg the first Dane, but not without proving their case: The authorities argued that they had climbed the wrong summit of Pobeda. Gilbertson embarked on another geographic investigation and soon settled the matter. The results are documented in The True Summit Location of Peak Pobeda.

How Does He Do It?

How does a 38-year-old assistant professor have the free time and spare cash to complete so many international expeditions? Gilbertson explains:

”I'm a teaching professor at Seattle University. This means I get about three months off every summer for mountaineering, and also winter and spring breaks between quarters. Sometimes I can get permission to overload my teaching schedule in a few quarters and take another quarter off. This was important for a peak like Kangchenjunga, which needs to be climbed in spring.“ As graduate students, Gilbertson and his brother, Matthew, were invited to international engineering conferences, which they paired with climbs.

“I try to be as frugal as possible,” he said. “Most of the European country high points I climbed as part of long-distance bicycle tours, camping in the woods every night, so transportation and lodging were basically free. I generally don’t pay for guides unless required by law. I sign up for airline credit cards to get free flights.” Gilbertson and his partners also maximize their efficiency and success rate during expeditions by paying for custom, satellite-delivered weather forecasts from Denver meteorologist Chris Tomer.

For Everest, Gilbertson hired the relatively inexpensive Seven Summit Treks (SST) for logistics and base camp services, then he climbed on his own above BC and did not pay for oxygen service (the same way he climbed K2 in 2022). As he was shopping for a guiding service, he negotiated for a multi-summit and multi-climber discount.

As events turned out, SST required Gilbertson to hire a Sherpa and use oxygen for his rapid Kangchenjunga ascent after Everest. “It would cost another $11K…and I could just barely afford that if I zeroed out my bank account,” Gilbertson wrote in his trip report. “That would be cheaper than losing all the money I’d already invested and then paying more a future year to come back. So I reluctantly agreed.”

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Interested in supporting this publication? Contact Heidi McDowell for opportunities. Got a potential story for the AAJ? Email us: aaj@americanalpineclub.org.