In 1925 Albert H. MacCarthy had just led a successful first ascent of Mount Logan in Canada, composed of climbers from Canada, Britain and the United States. MacCarthy, an American and member of the American Alpine Club, wrote a number of reports and summaries of the expedition, including this list of Mountain “Dont’s.”

Pitons

by Allison Albright

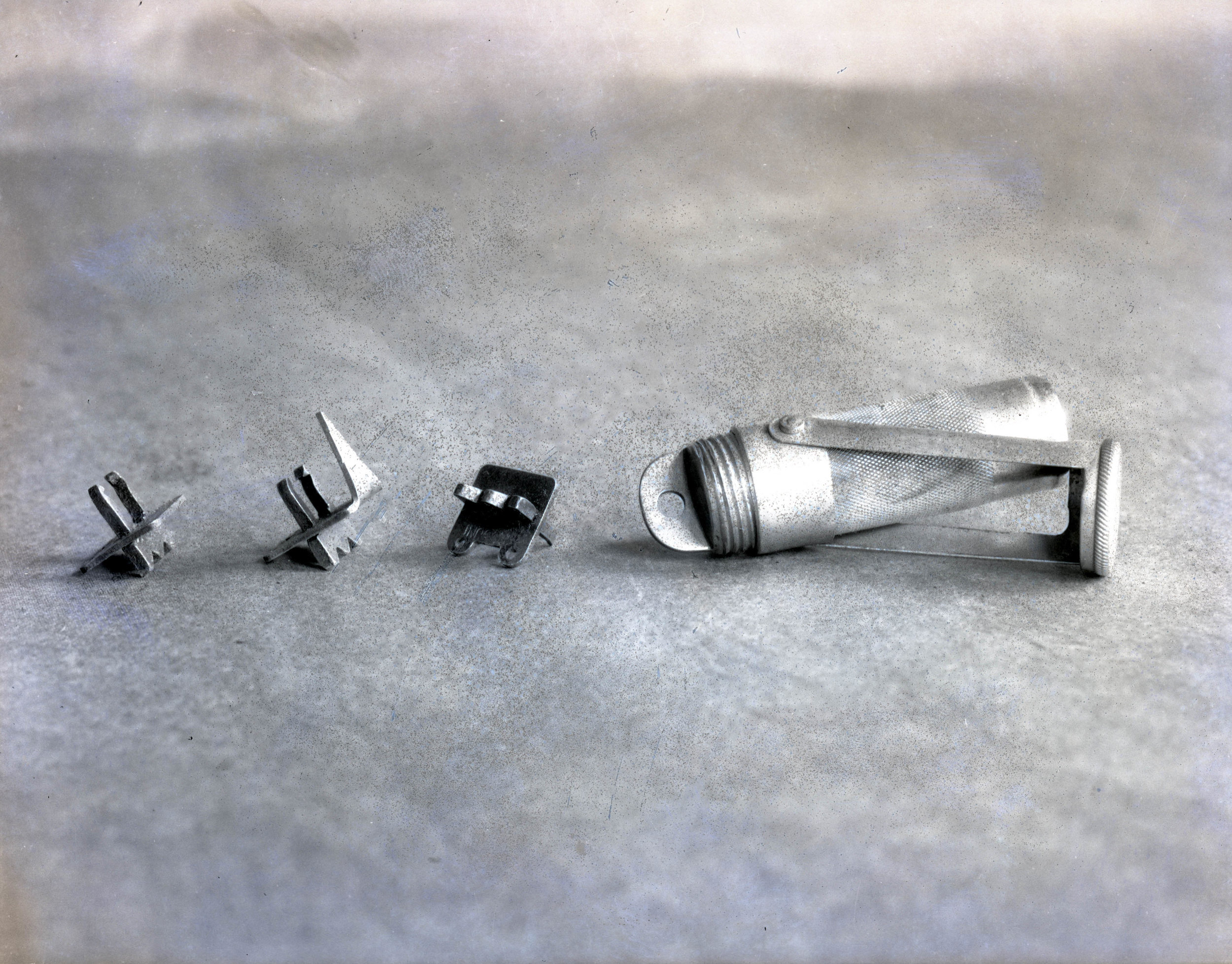

A set of pitons from the mid-20th century, including LEM, Charlet-Moser, Stubai and Chouinard

Pitons are one of the oldest types of rock protection and were invented by the Victorians in the late 19th century. Pitons are metal spikes which are inserted into cracks in the rock and secured by hammering them into place with a piton hammer.

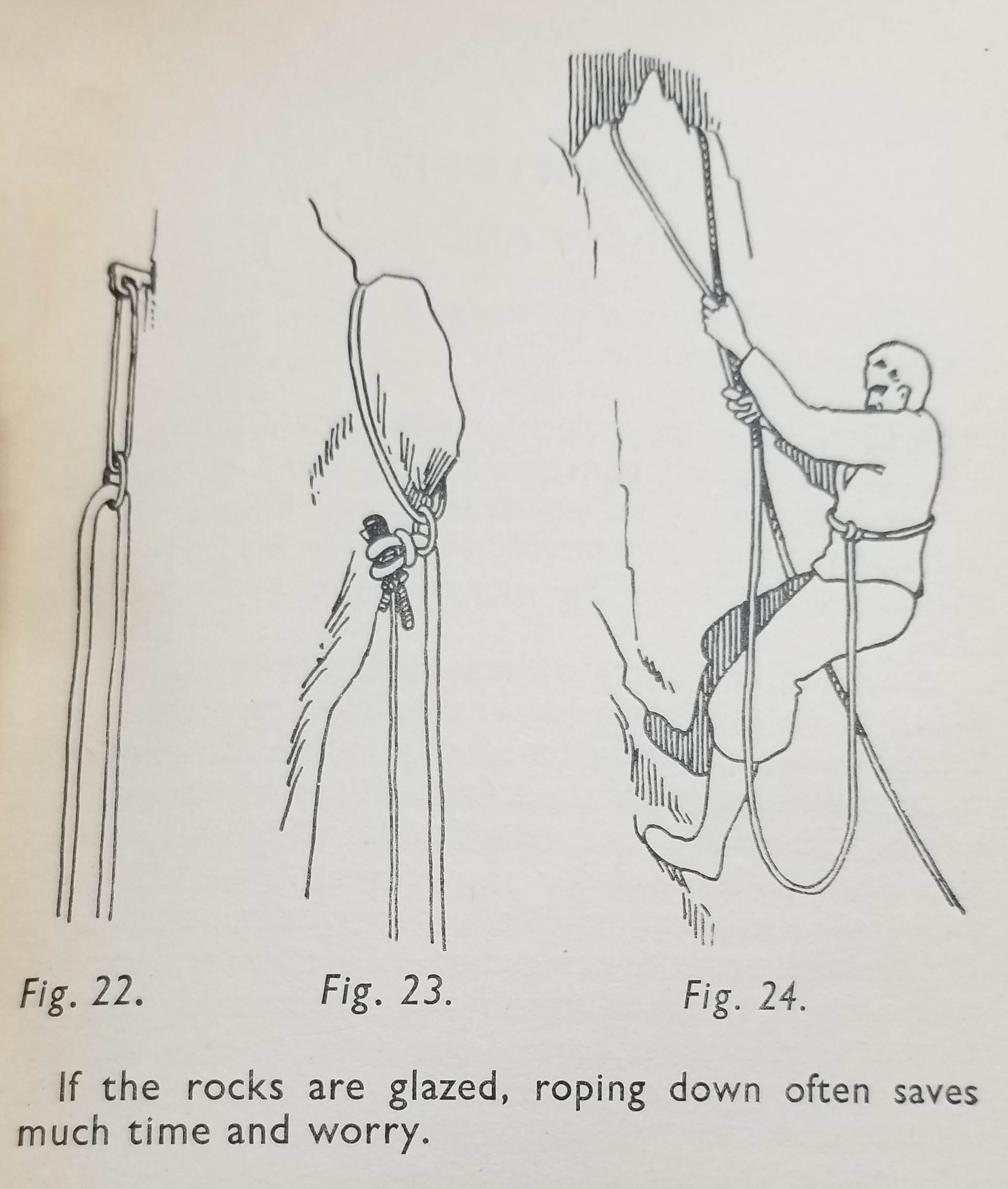

Illustration of a climber using natural protection methods to rope down from Alpine Climbing on Foot and with Ski by Ernest Wedderburn, 1937

Mountaineering involved technical rock climbing only as a means to reach the top of the mountain, and not, in those days, for its own sake and by the turn of the 20th century, most mountain climbers favored “natural protection,” which was securing rope to rocks or other natural features that could be found along the route. They used pitons nearly exclusively for climbing down and only then when the route down had become unsafe due to the sun setting or ice forming on rocks. This was especially true of UK mountaineers, who prided themselves on their ability to climb without the use of such aids.

Many mountaineers in those days believed that the use of artificial rock protection and aids, such as pitons, would lead to carelessness and were regarded as useless in the ascent of difficult routes.

Early pitons were iron spikes and had rings attached to one end through which mountaineers would secure their rope. However, those rings sometimes bent or broke under the weight of a mountaineer. Hans Fiechtl invented the modern piton in 1910, made entirely of one piece of metal with a hole (called the eye) in one end. This reduced the number of moving parts in the tool and made them sturdier and more reliable.

Illustration of piton use and placement from the Handbook of American Mountaineering by Kenneth Henderson, 1942

“In such cases, pegs to hammer in and anchor to are a remedy for our failures, our failure to carry on, to adjust the climb to the day-length, or to watch the weather. Their use then is corrective, not auxiliary.”

Angle piton with a ring

Illustration of proper piton technique from the Handbook of American Mountaineering by Kenneth Henderson, 1942

Pitons were mostly made of softer steel and iron that allowed them to conform to the shape of the crack when used, making it difficult or impossible to remove them from the rock when they were no longer needed. This method worked well in the softer rock of Europe and much of the US, and pitons were habitually left in place at the end of a climb.

However, leaving permanent marks on the landscape sat poorly with many climbers and soft pitons didn’t work well on longer routes where rock protection needed to be removed and used again. They also didn’t hold up well in the hard granite of places like the Yosemite Valley. In 1946 John Salathé, a climber and a blacksmith, used hardened steel to create pitons that could be removed from a crack and used again and again without getting bent or disfigured.

A lost arrow piton with sunburst design

The only problem with the harder pitons was that they often disfigured the rock. Since pitons are hammered into and out of rock cracks, and since the same cracks are often used over and over again, climbers were leaving their mark each time they inserted and removed a hard steel piton. The soft steel pitons weren’t much better at leaving a route unaltered, since they often had to be left in place. They can still be found in some routes.

“There is a word for it, and the word is clean.” – Doug Robinson, The Whole Natural Art of Protection, 1972

Yvon Chouinard, who had been making pitons through his Chouinard Equipment brand for several years by then, introduced the aluminum chocks in his 1972 Chouinard Equipment/Great Pacific Iron Works catalog. The catalog included two seminal essays on clean climbing; A Word by Yvon Chouinard and Tom Frost, and The Whole Natural Art of Protection by Doug Robinson. You can read them online here. This ethos changed American climbing forever and the piton was quickly replaced by equipment that could be easily removed and reused without damaging or altering the rock, first slings, nuts and chocks and later cams.

Pitons manufactured by Yvon Chouinard, arranged in order of their evolution.

Clean climbing methods proved to be much safer and easier to use than pitons, since pounding a spike into a crack with a hammer is time and energy consuming. Pitons are still used in some places where other types of protection aren’t an option, but these situations are rare.

You can check out some examples of pitons from our archival gear collection in the slideshow below.

Denali - First ascent of the South Face via the West Rib 1959

It had all begun on an afternoon some nine months previous. Four of us were lying about relaxing after a particularly fine Teton climb when someone enthusiastically suggested, "Let’s climb the south face of McKinley next summer!” To attempt a new and difficult route on North America’s highest mountain seemed a most worthwhile enterprise; without further ado, we cemented the proposal with a great and ceremonious toast.

The Andrew J. Gilmour Collection

by Allison Albright

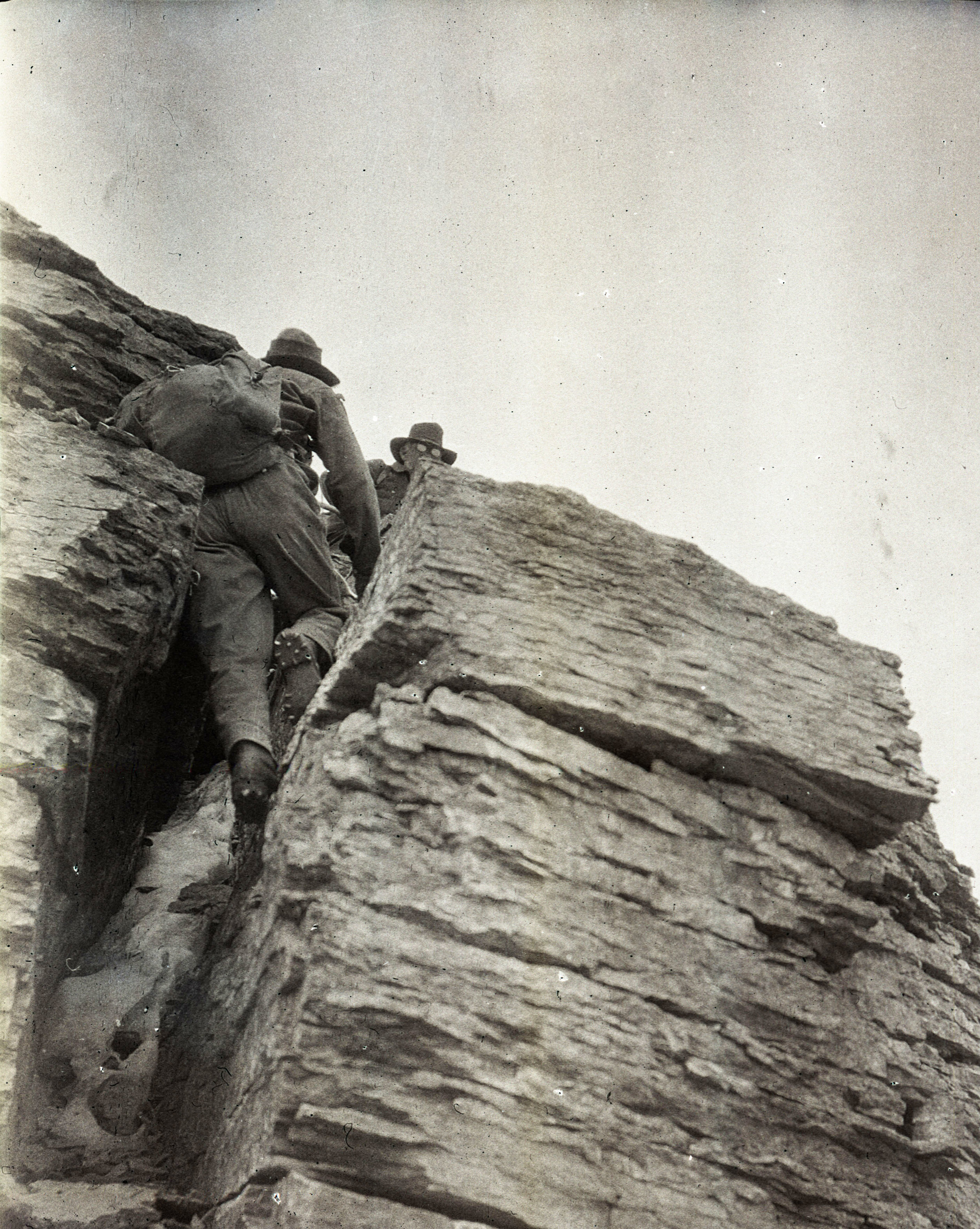

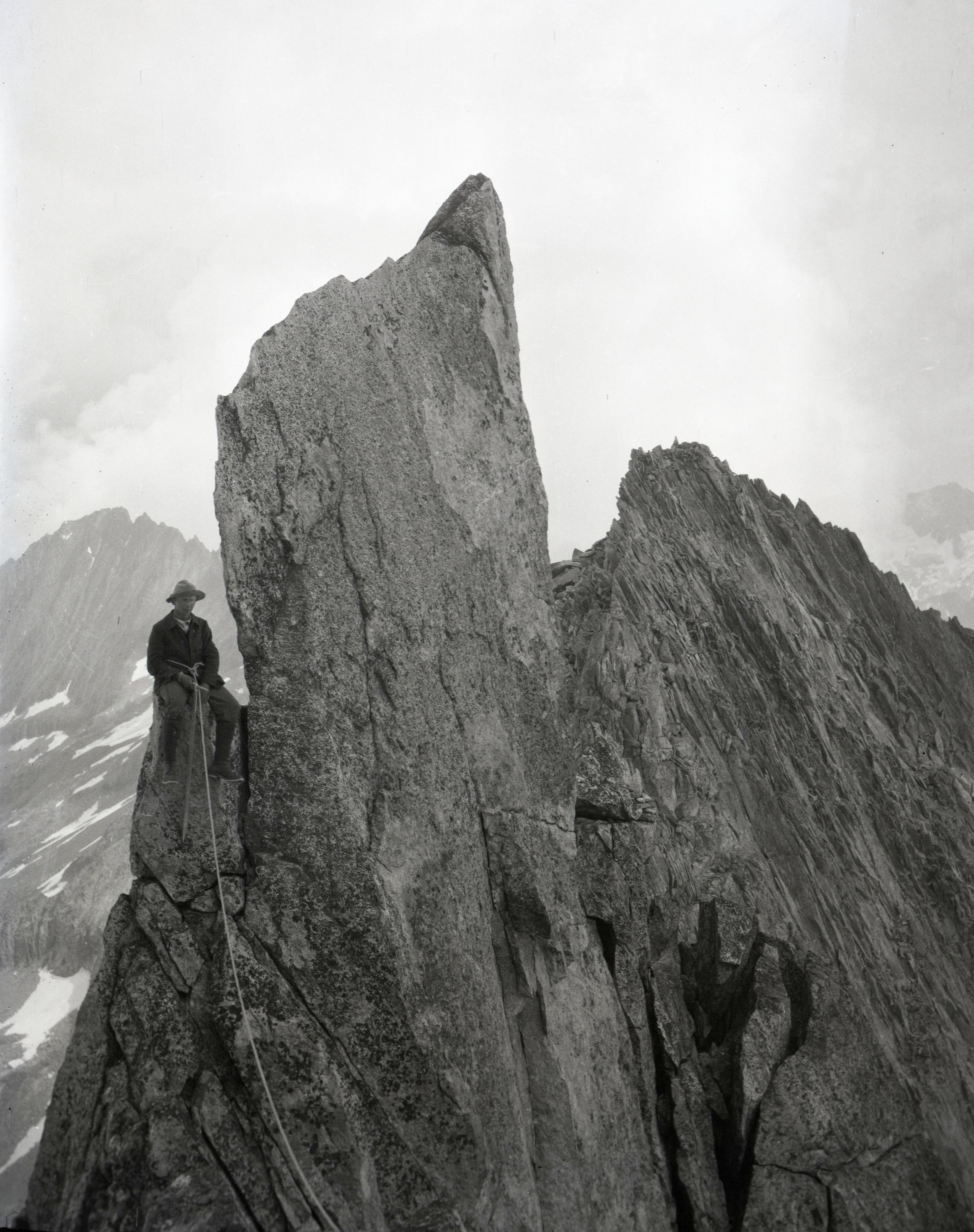

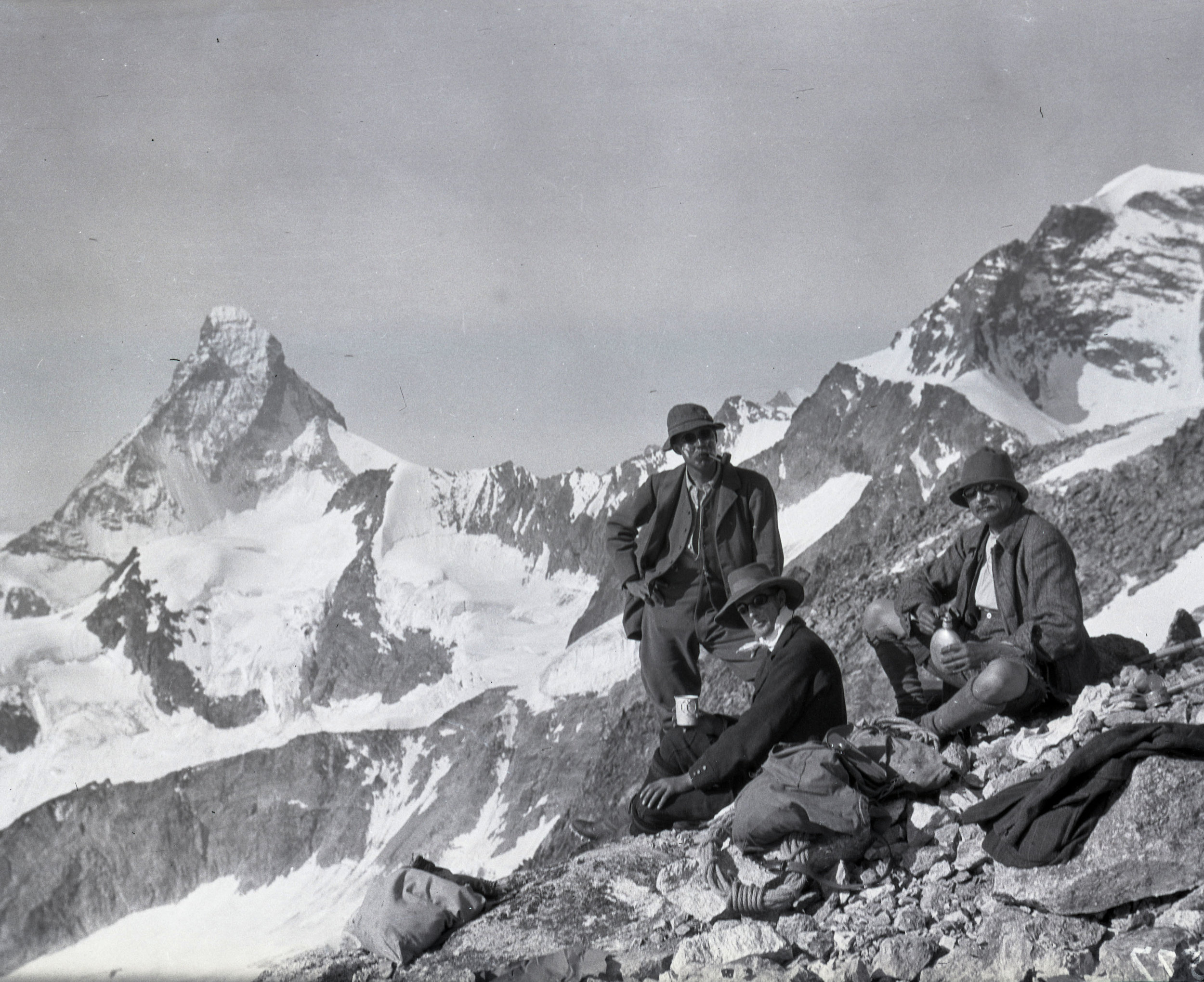

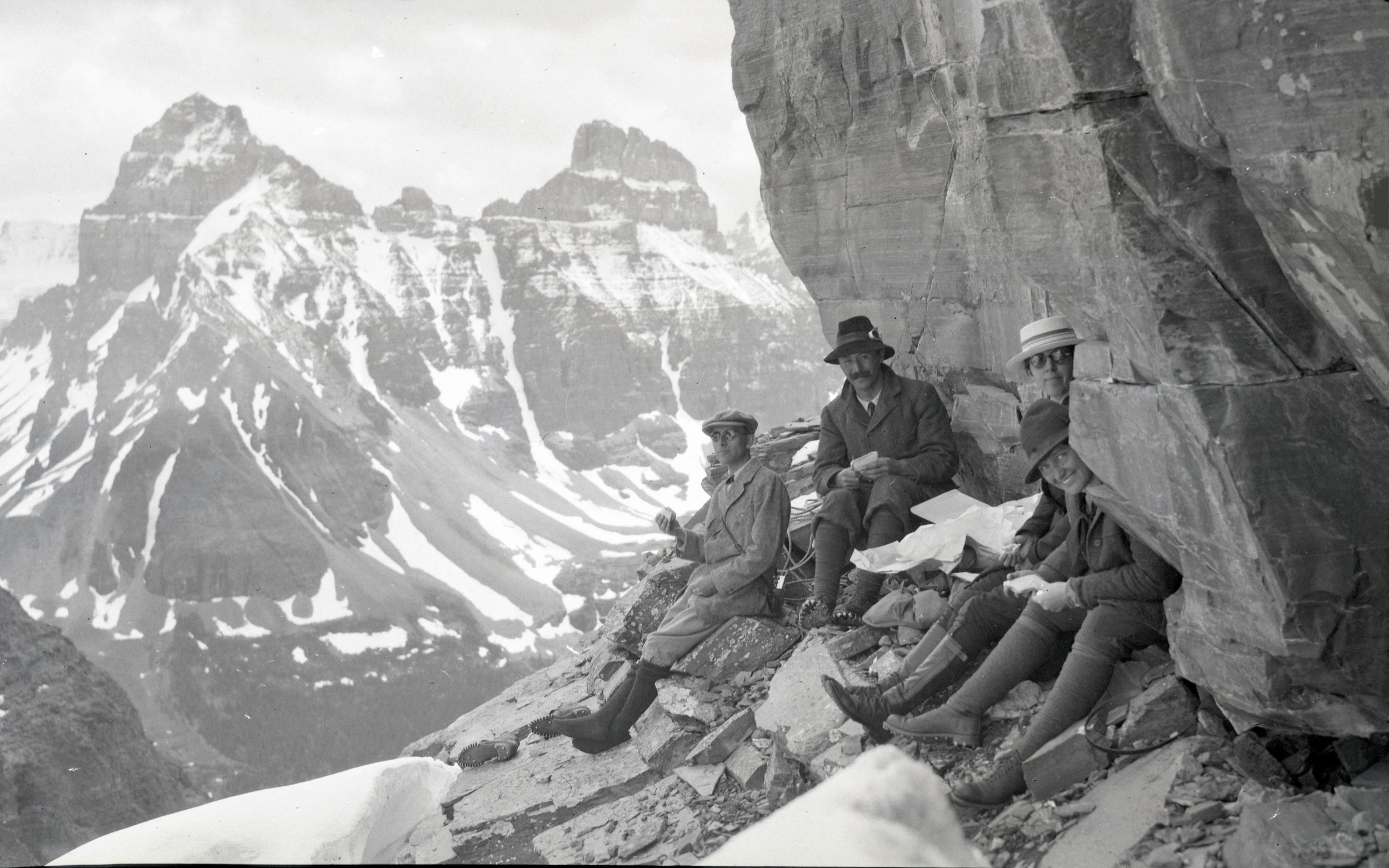

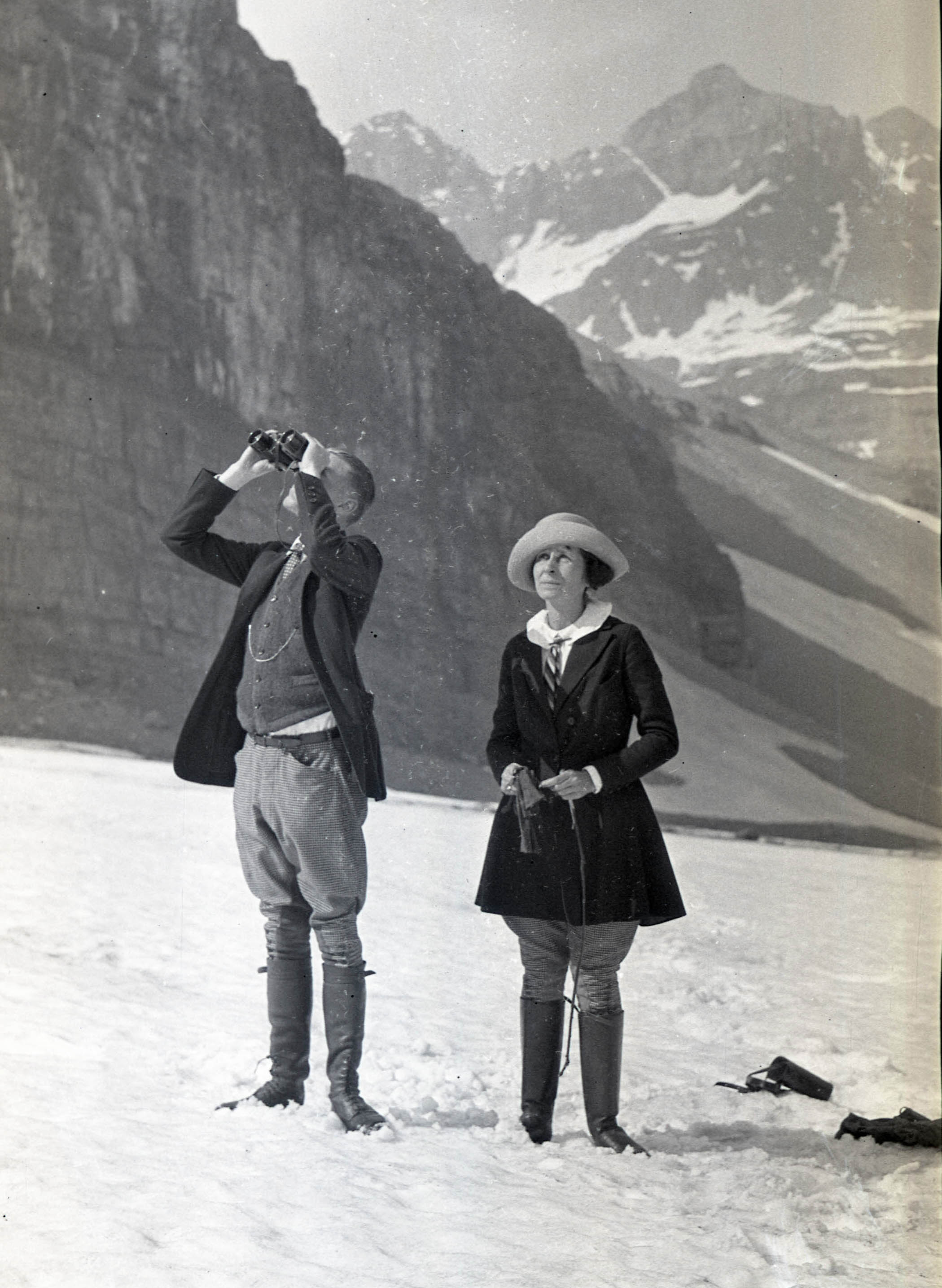

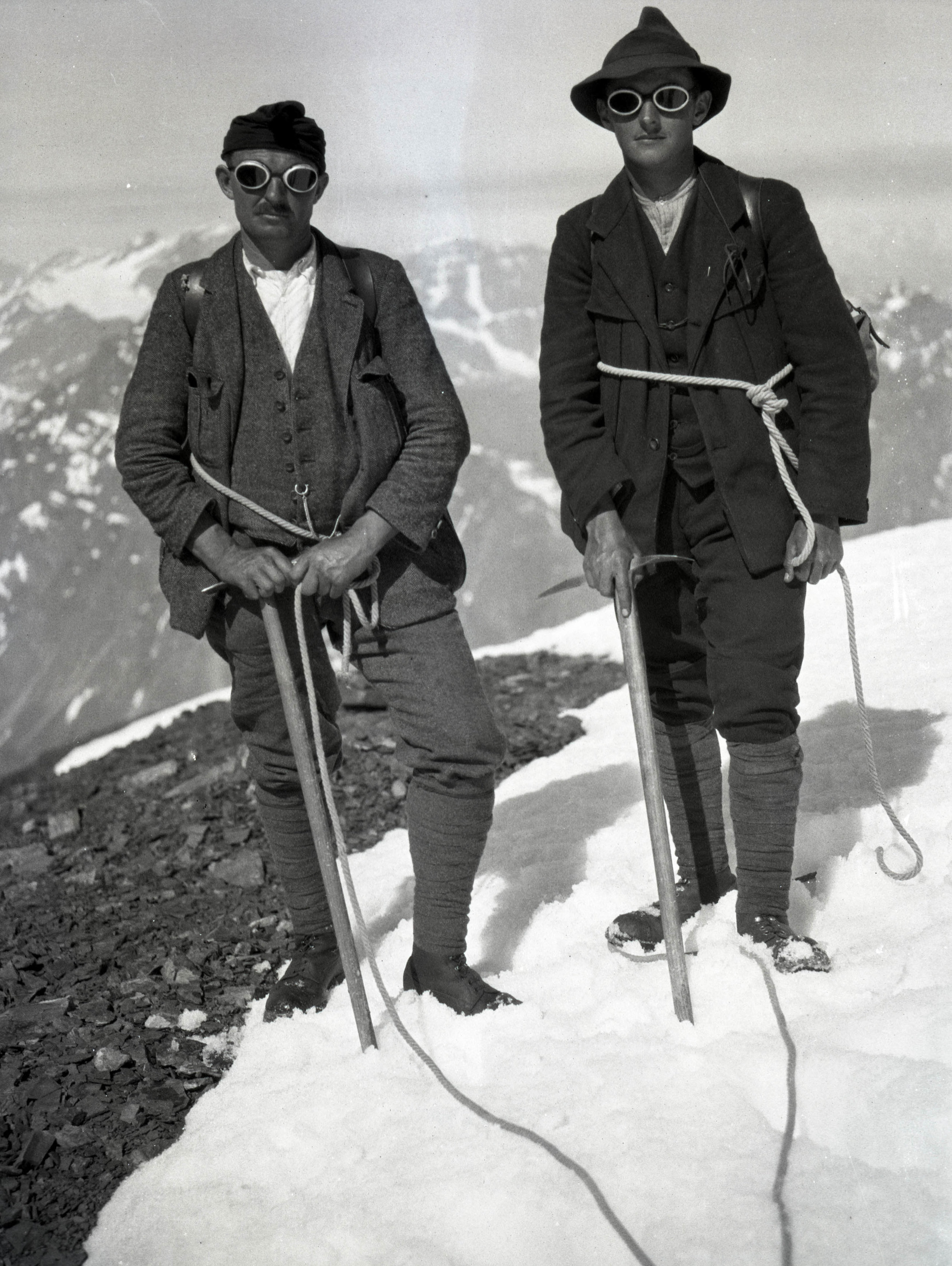

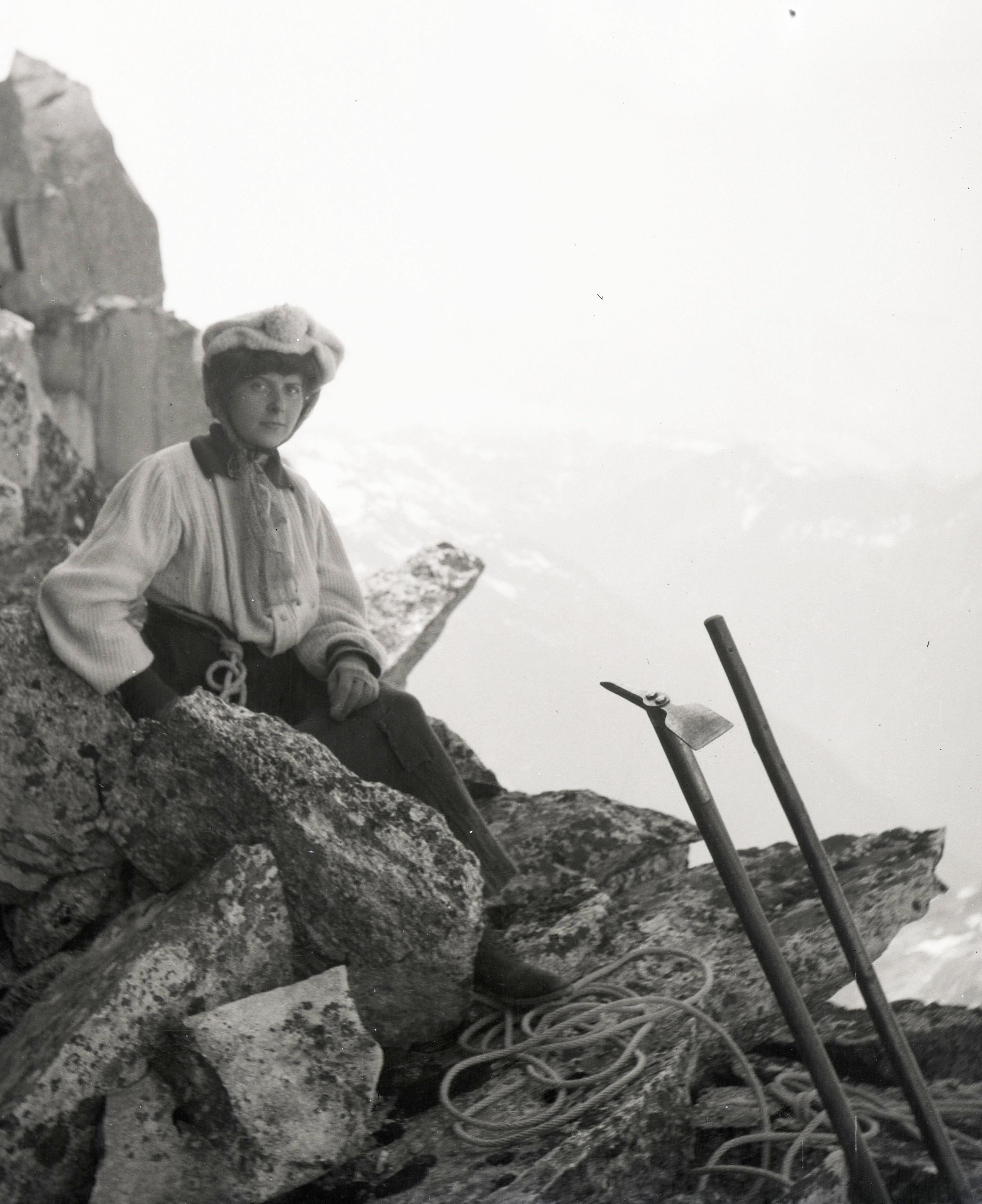

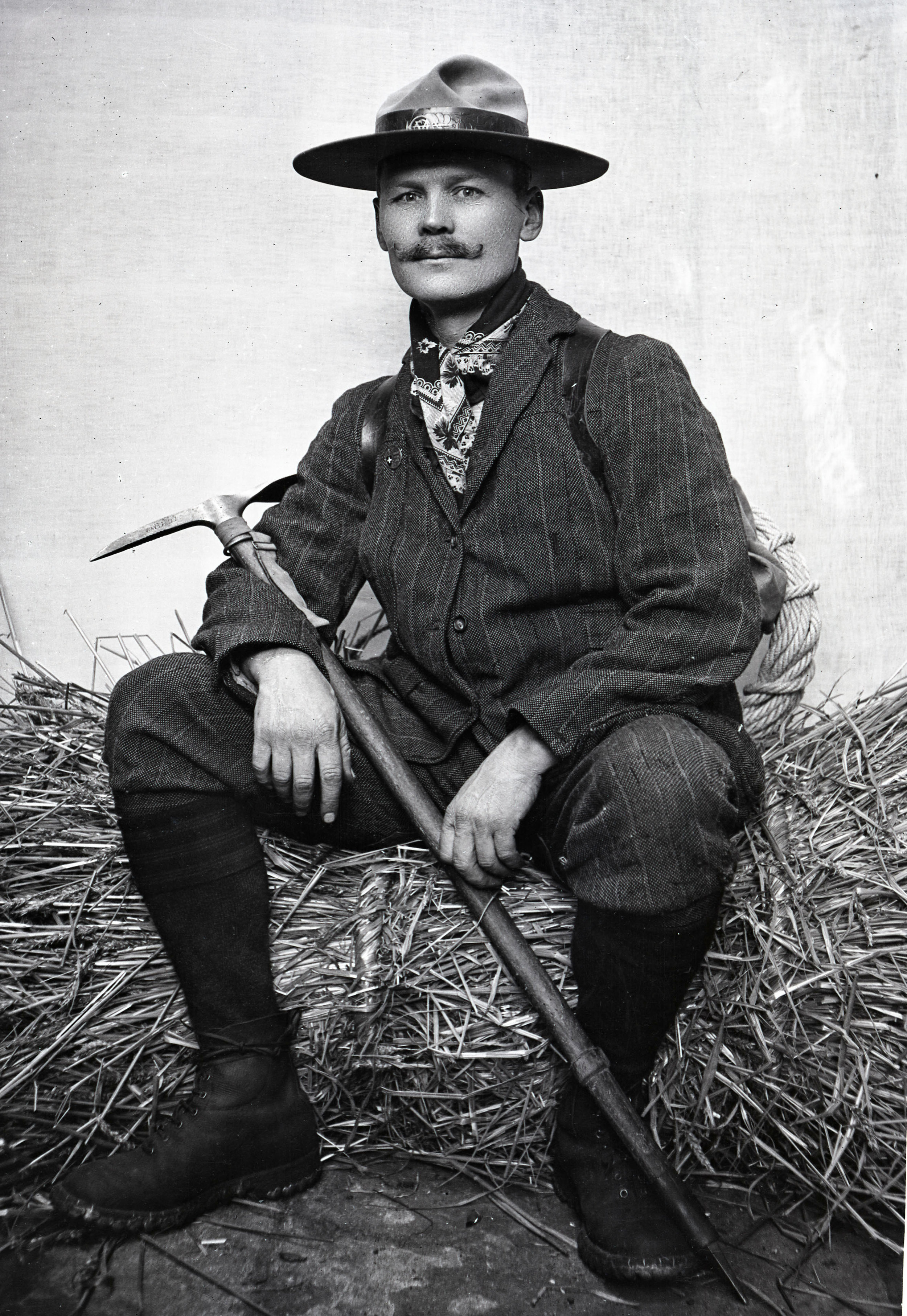

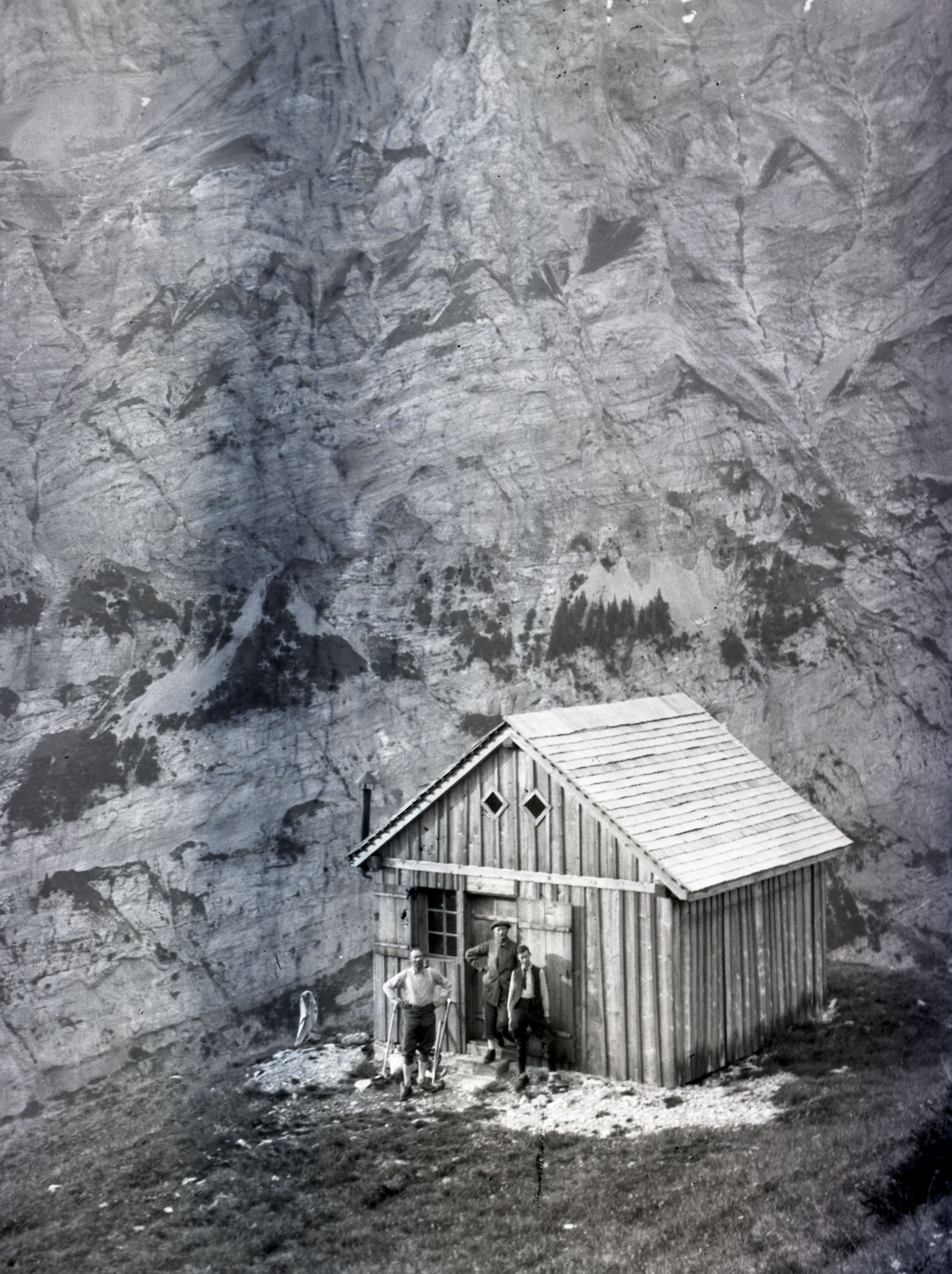

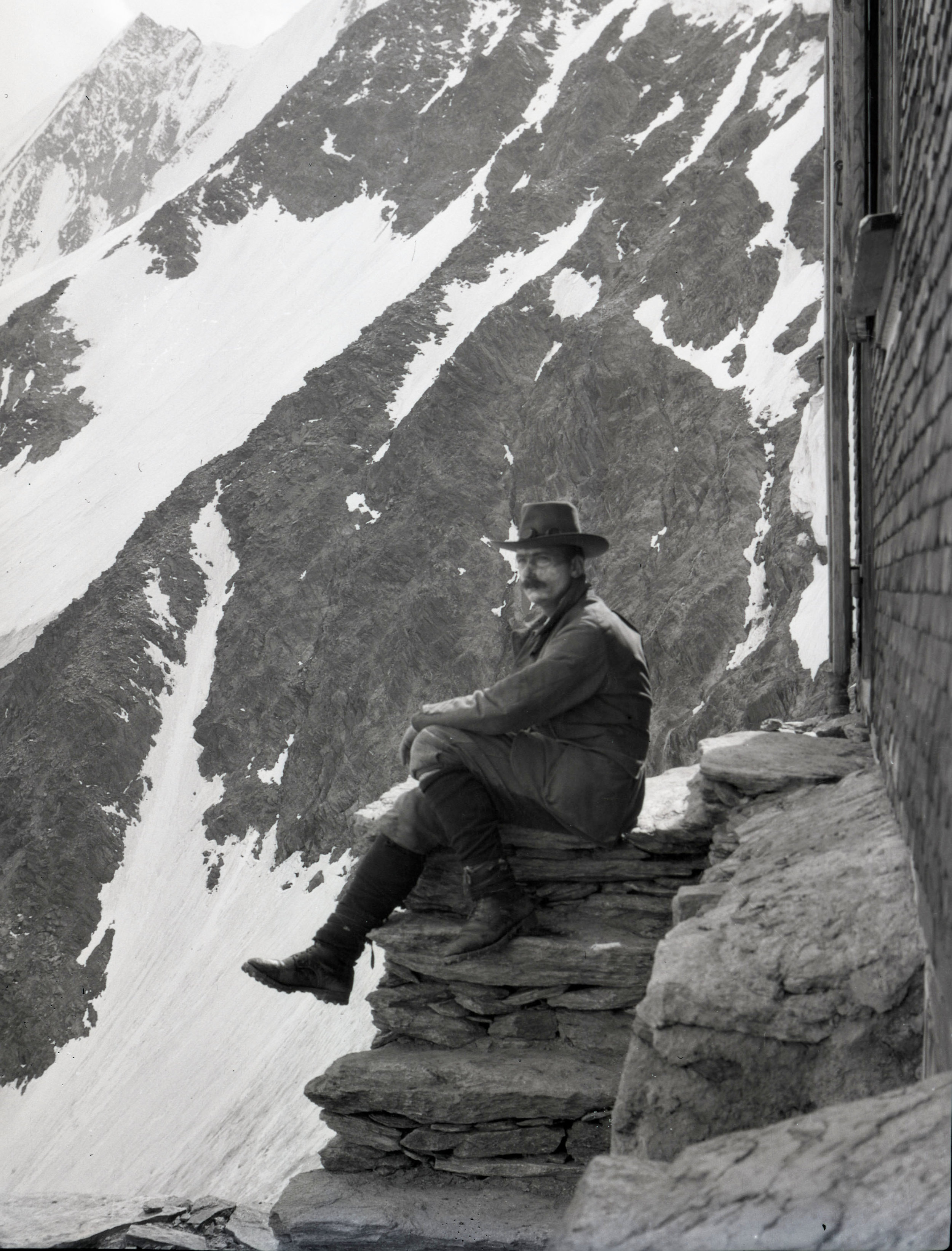

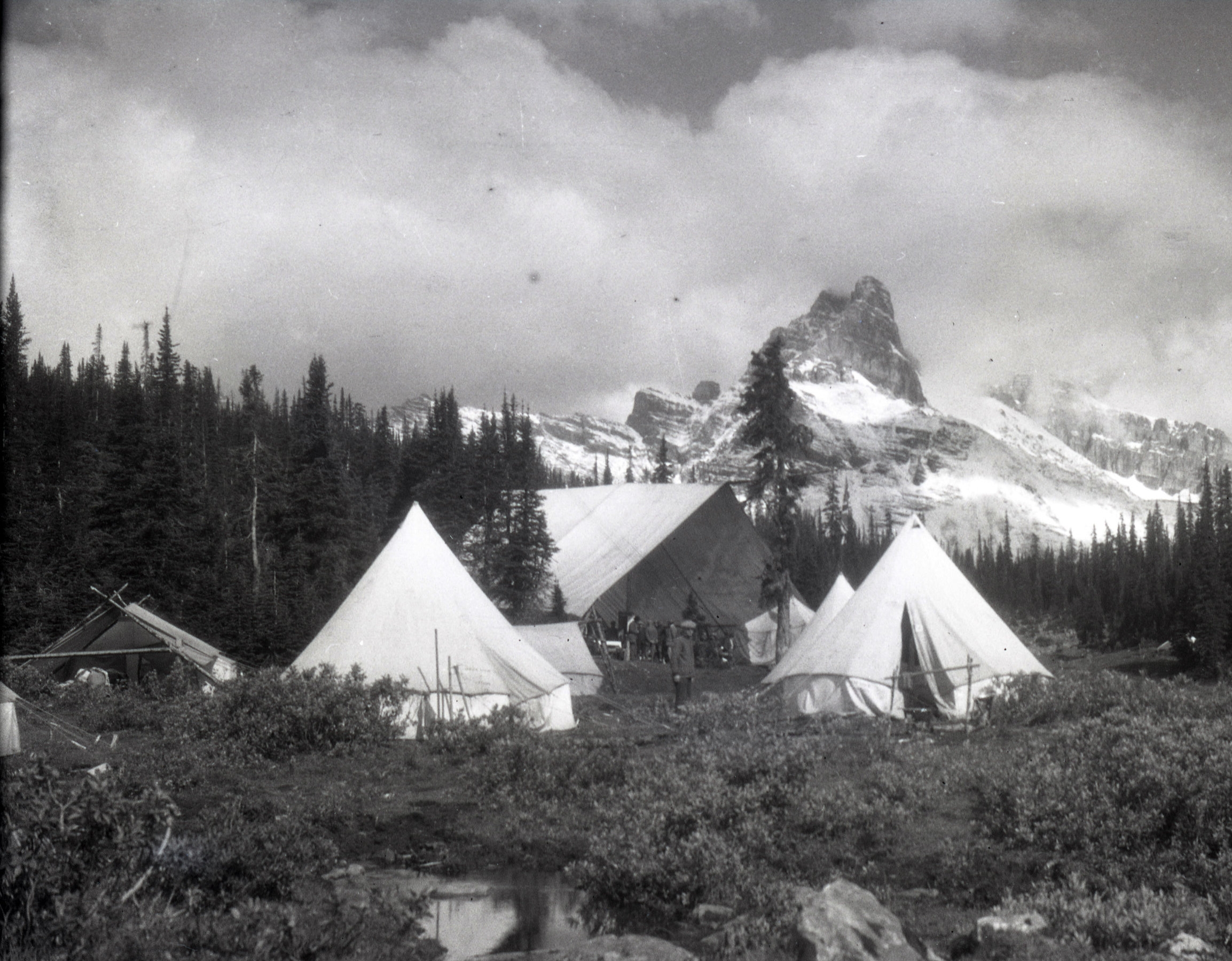

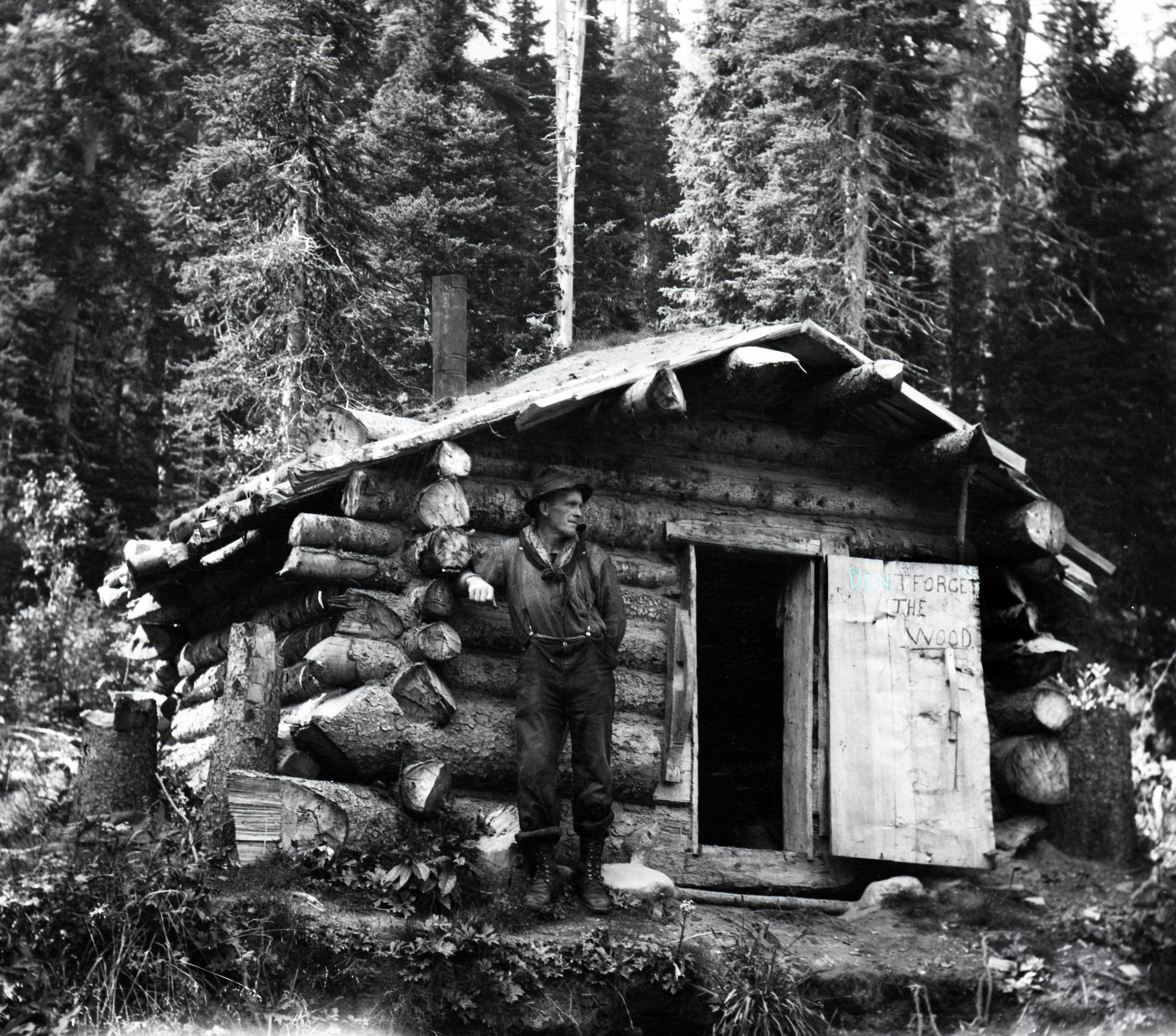

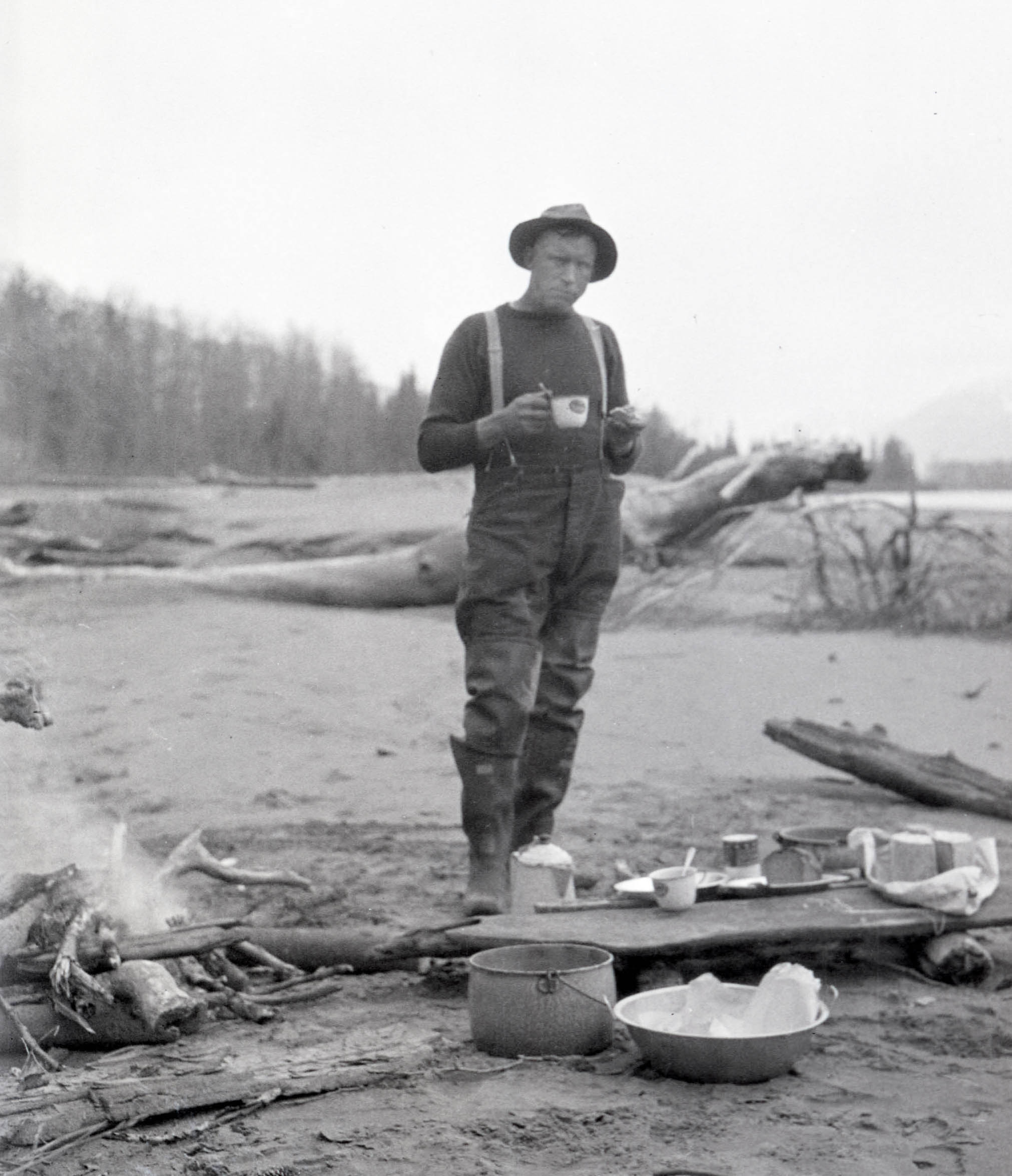

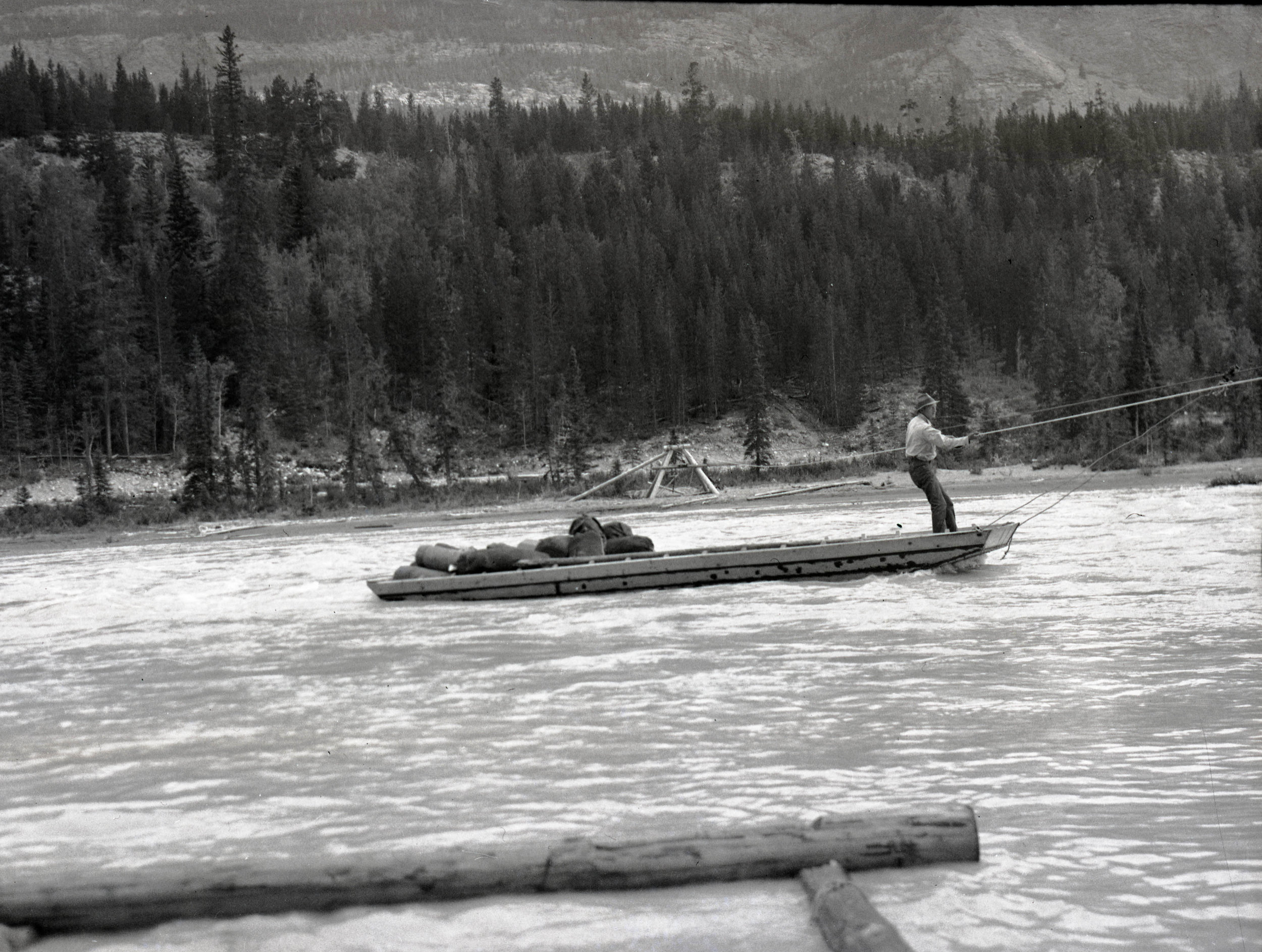

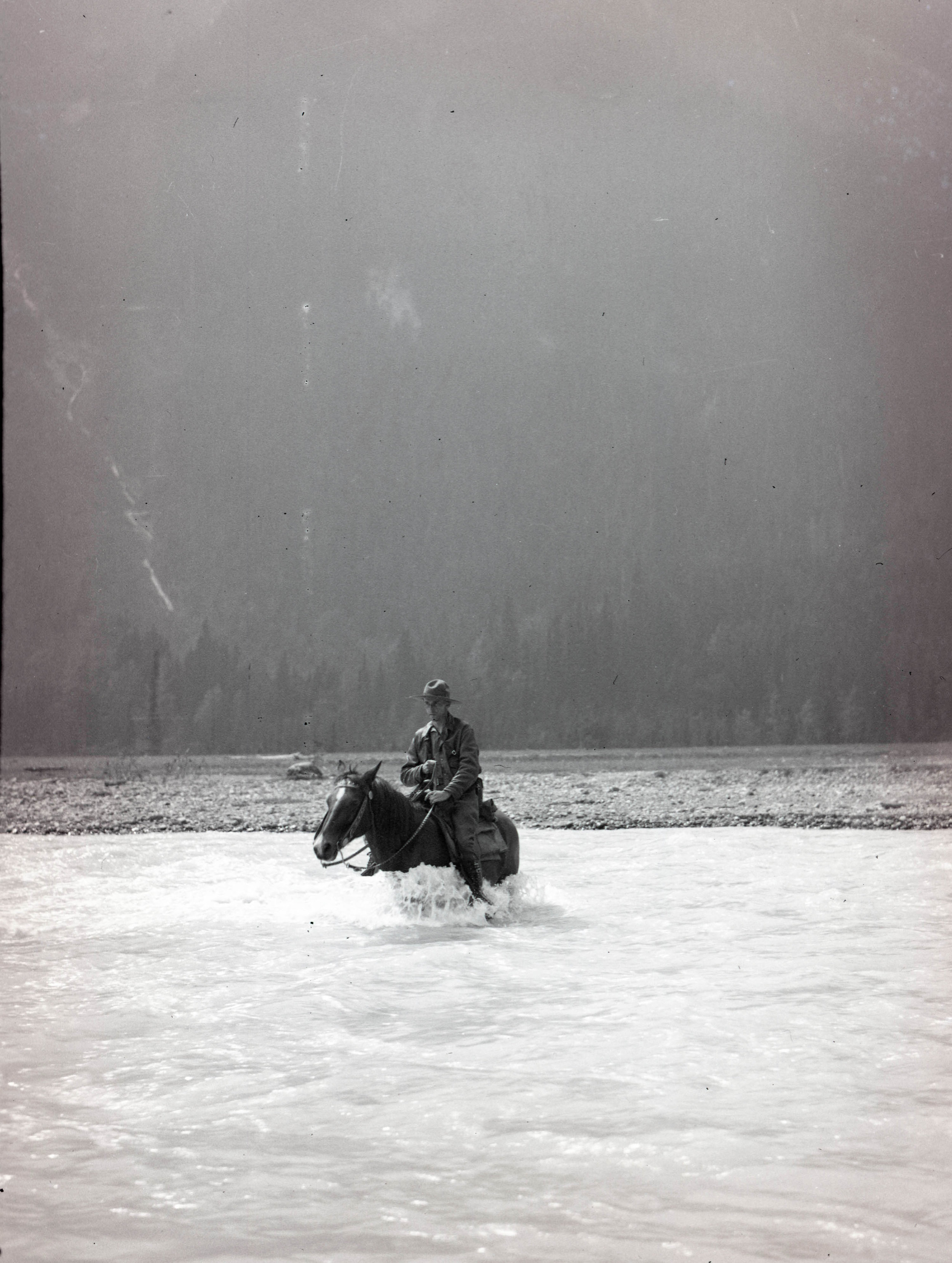

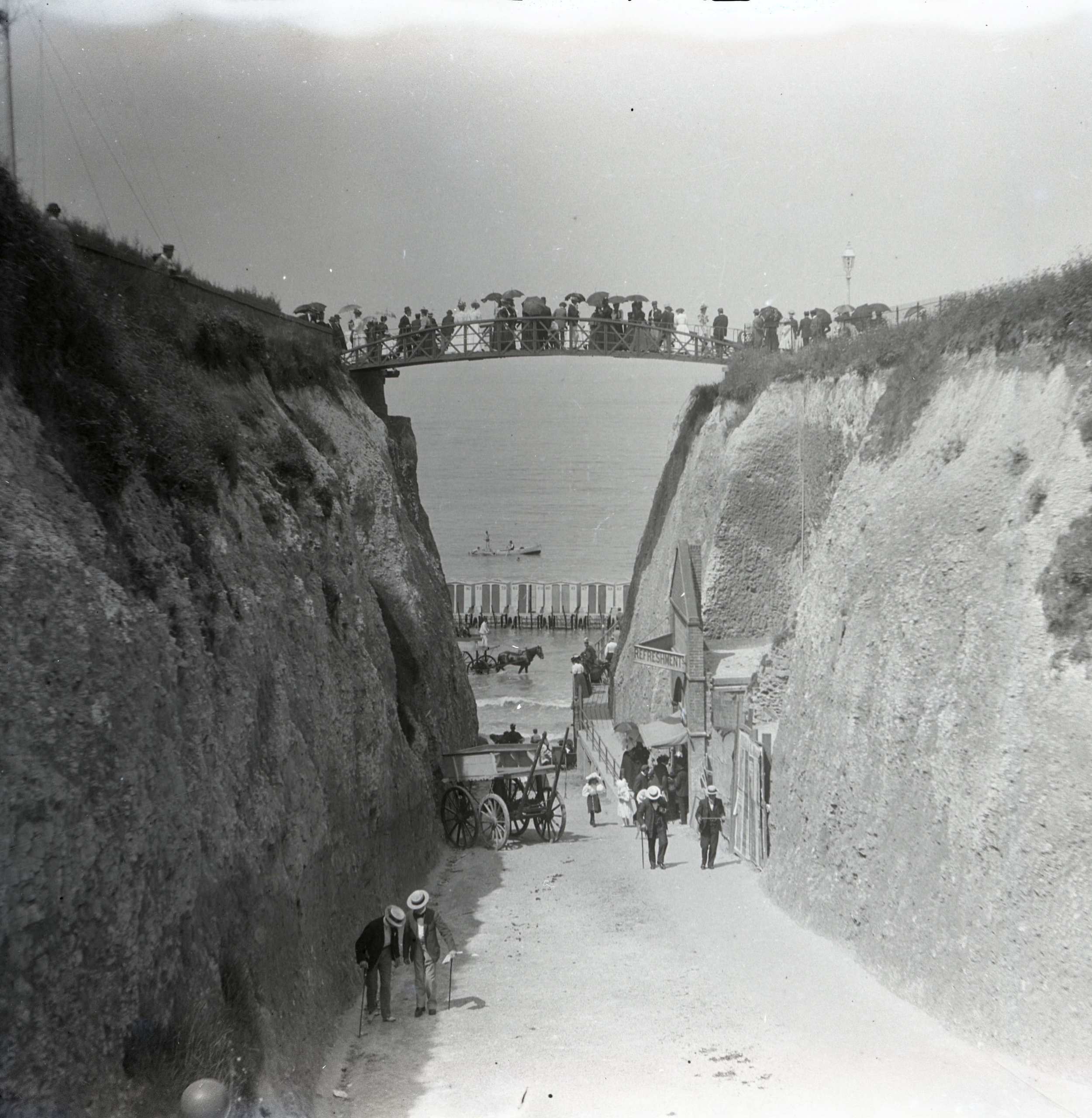

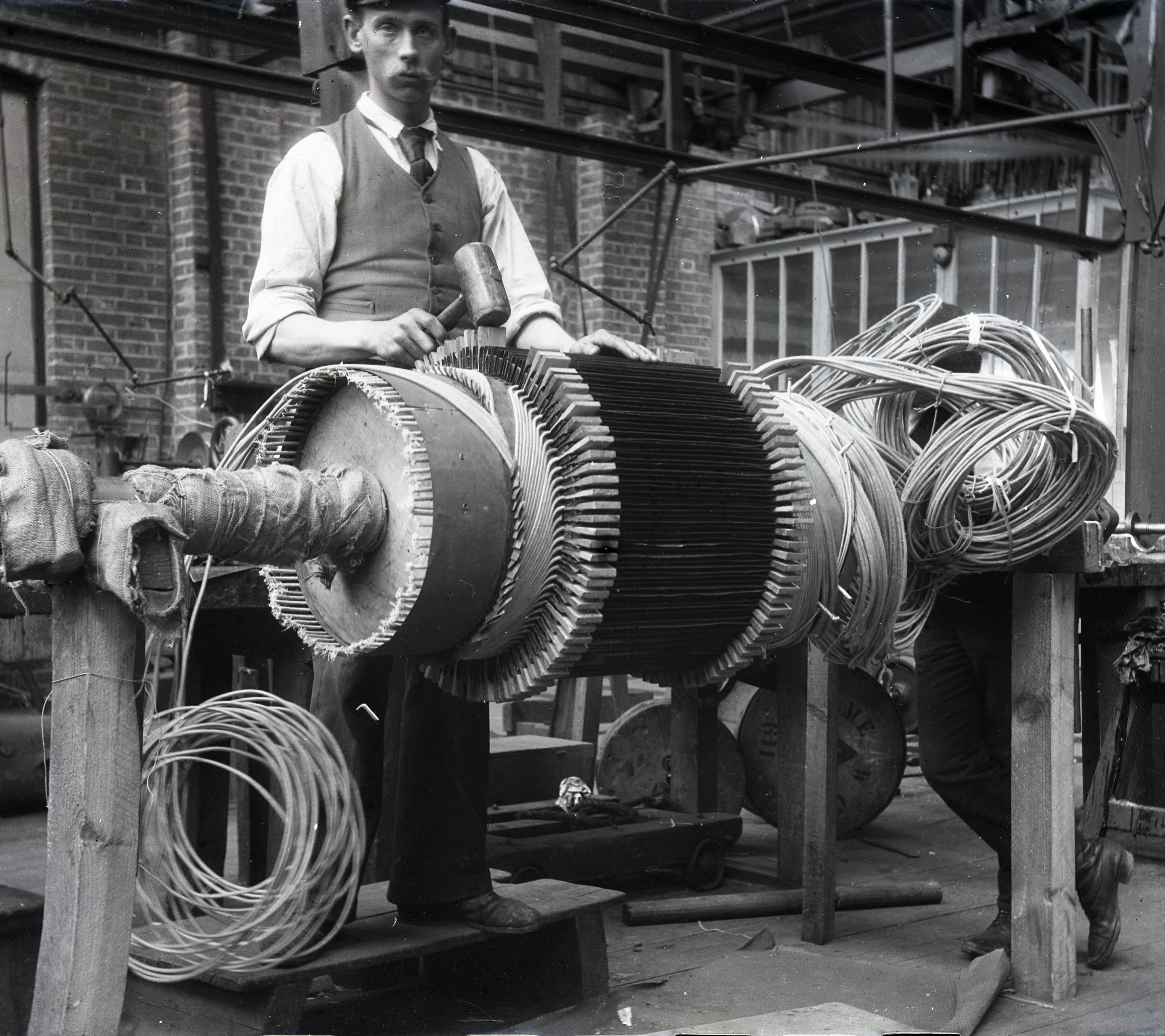

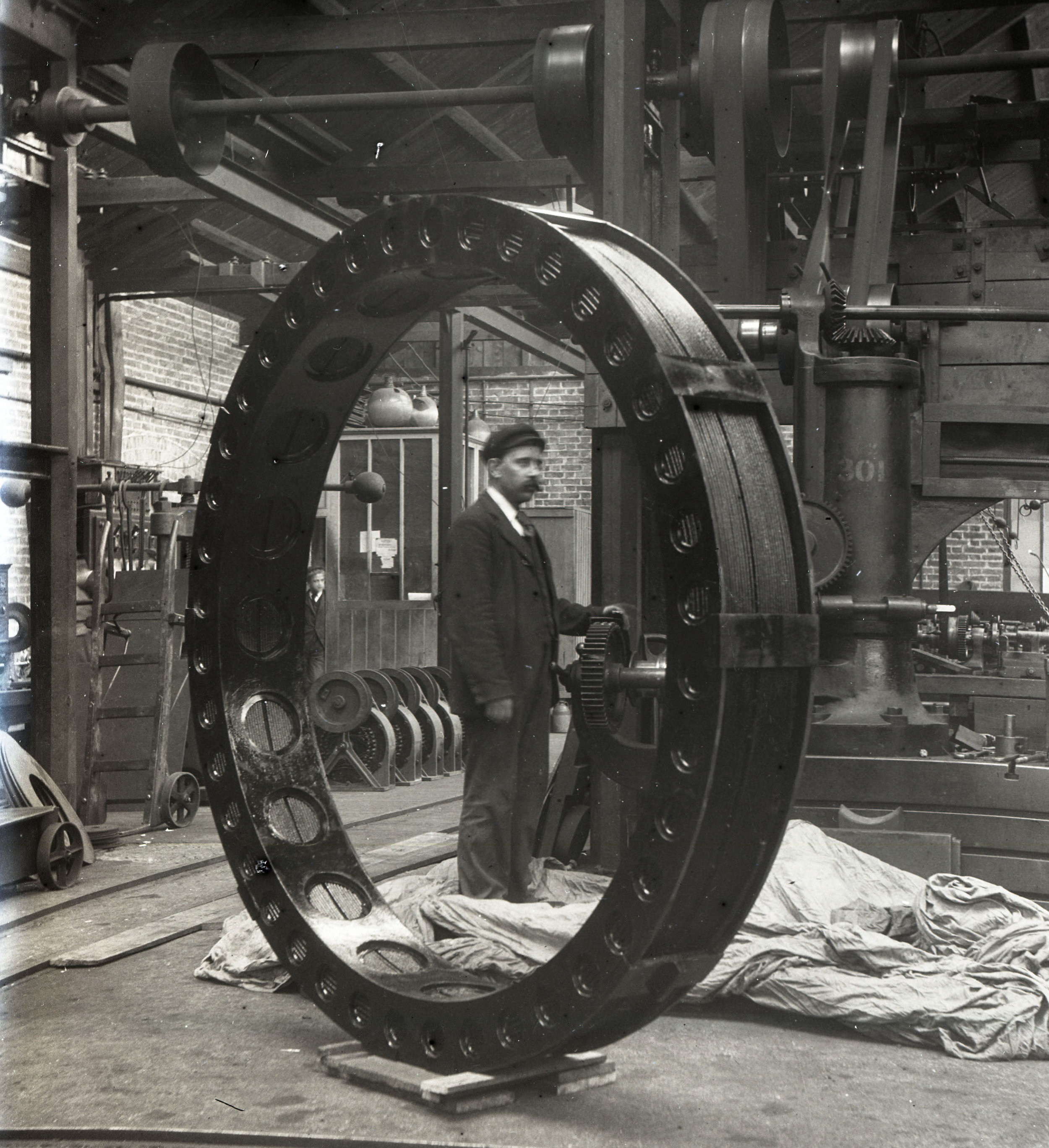

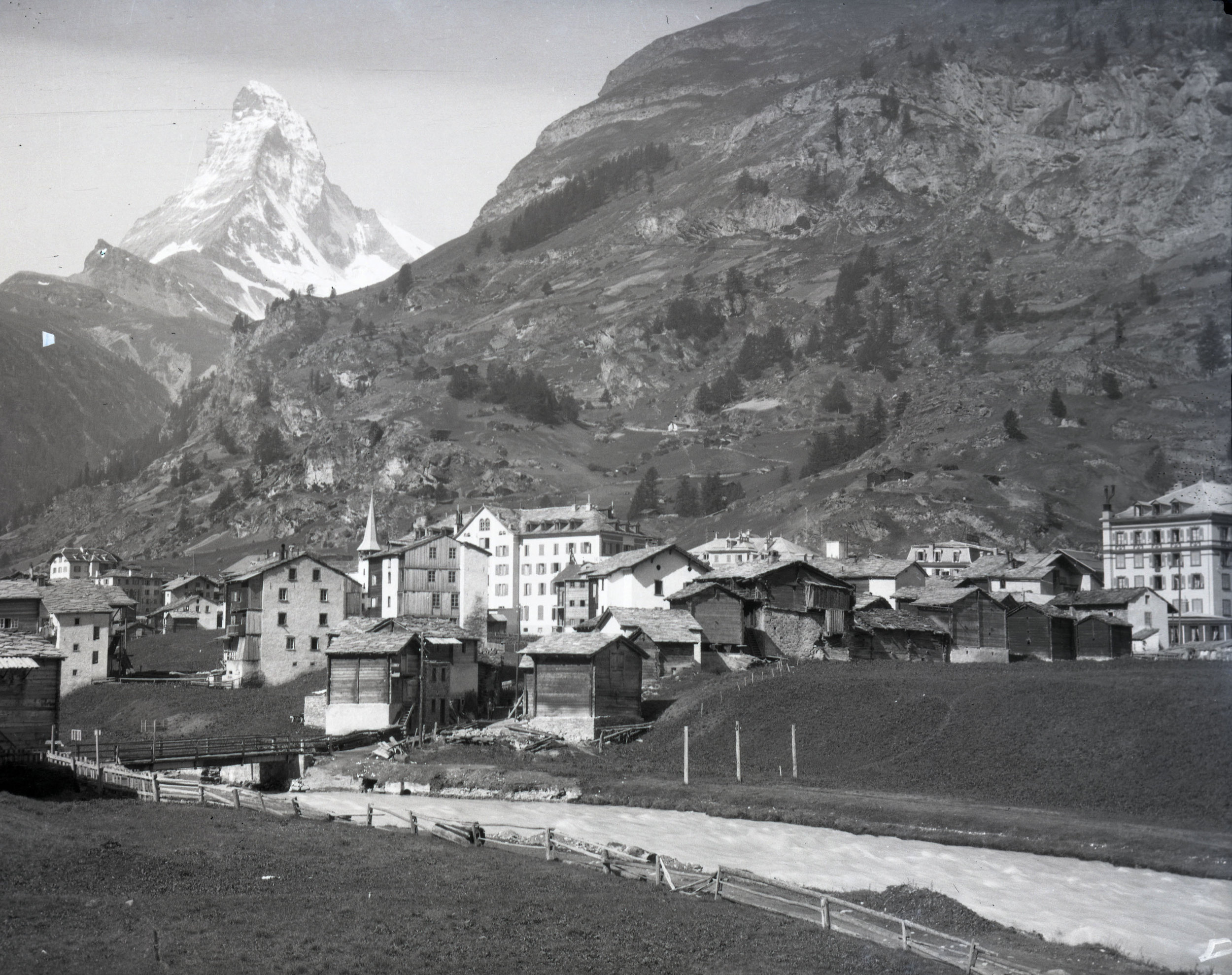

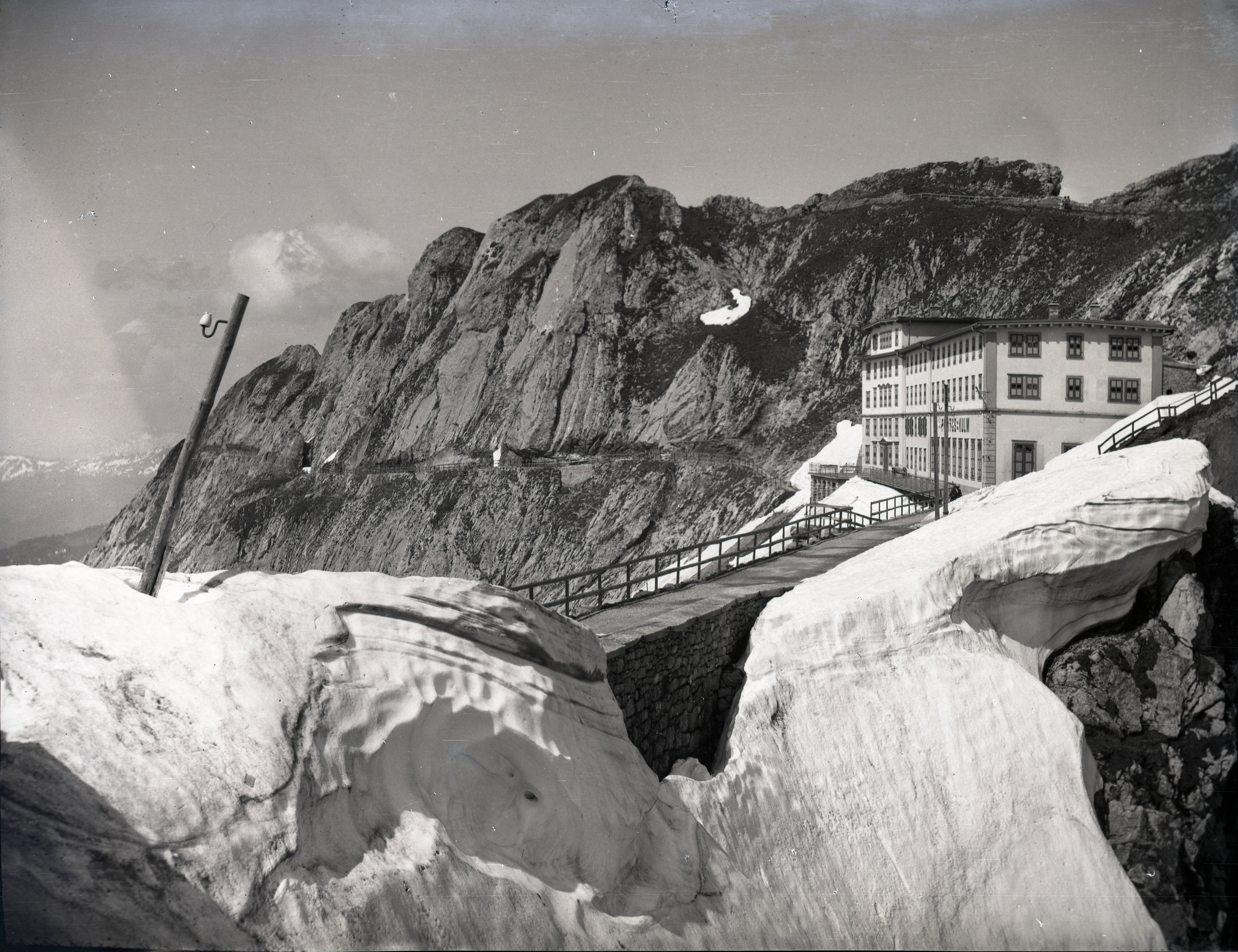

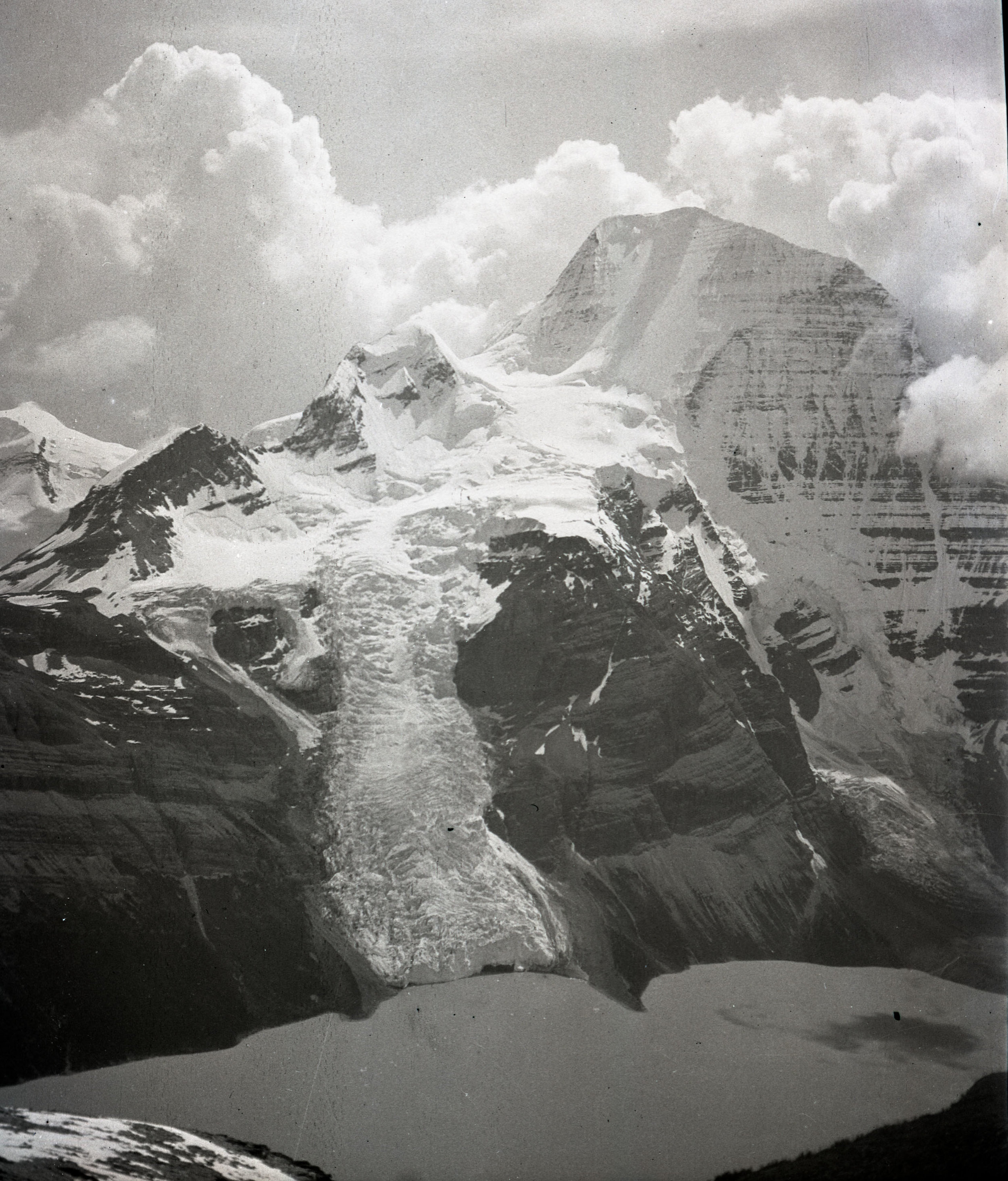

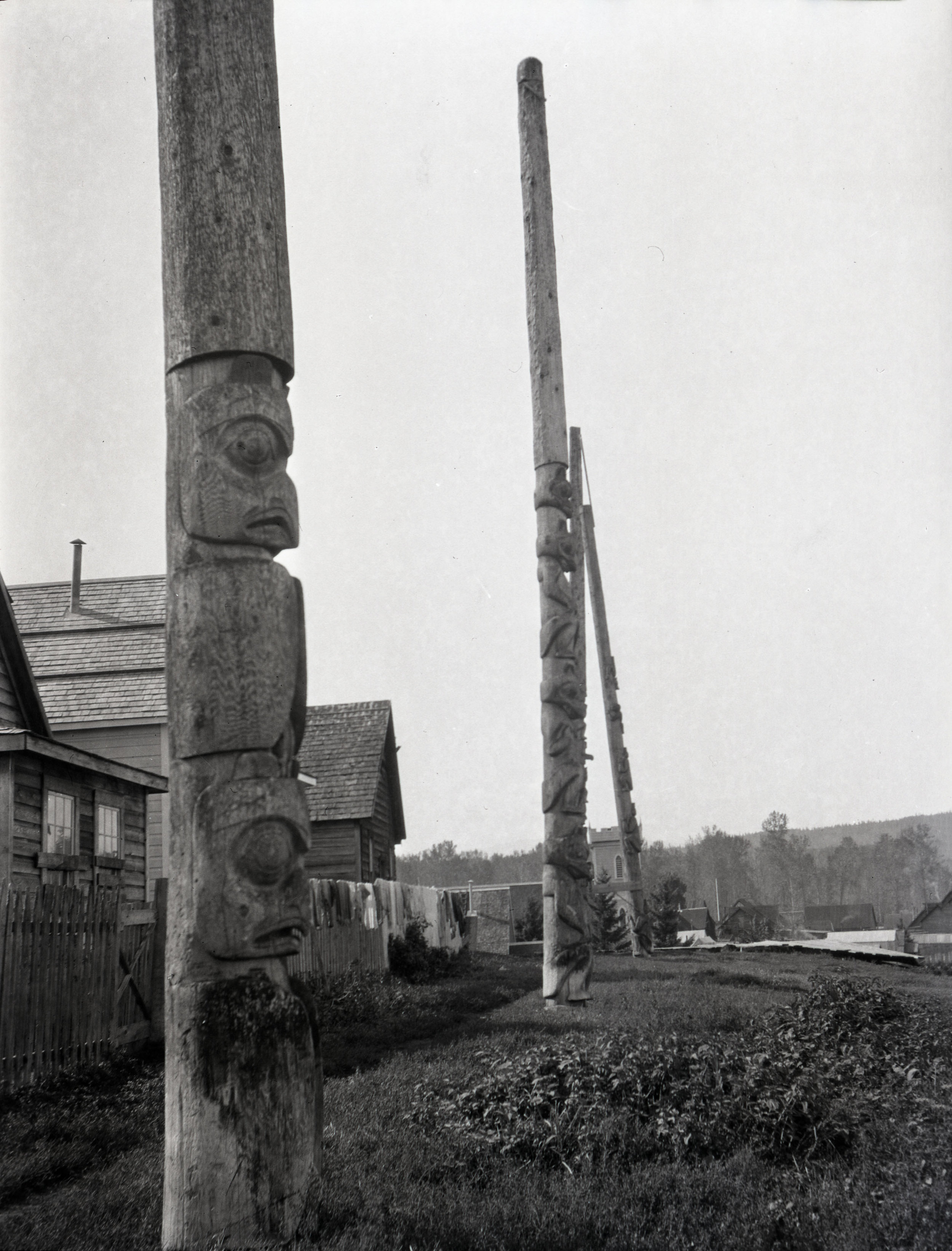

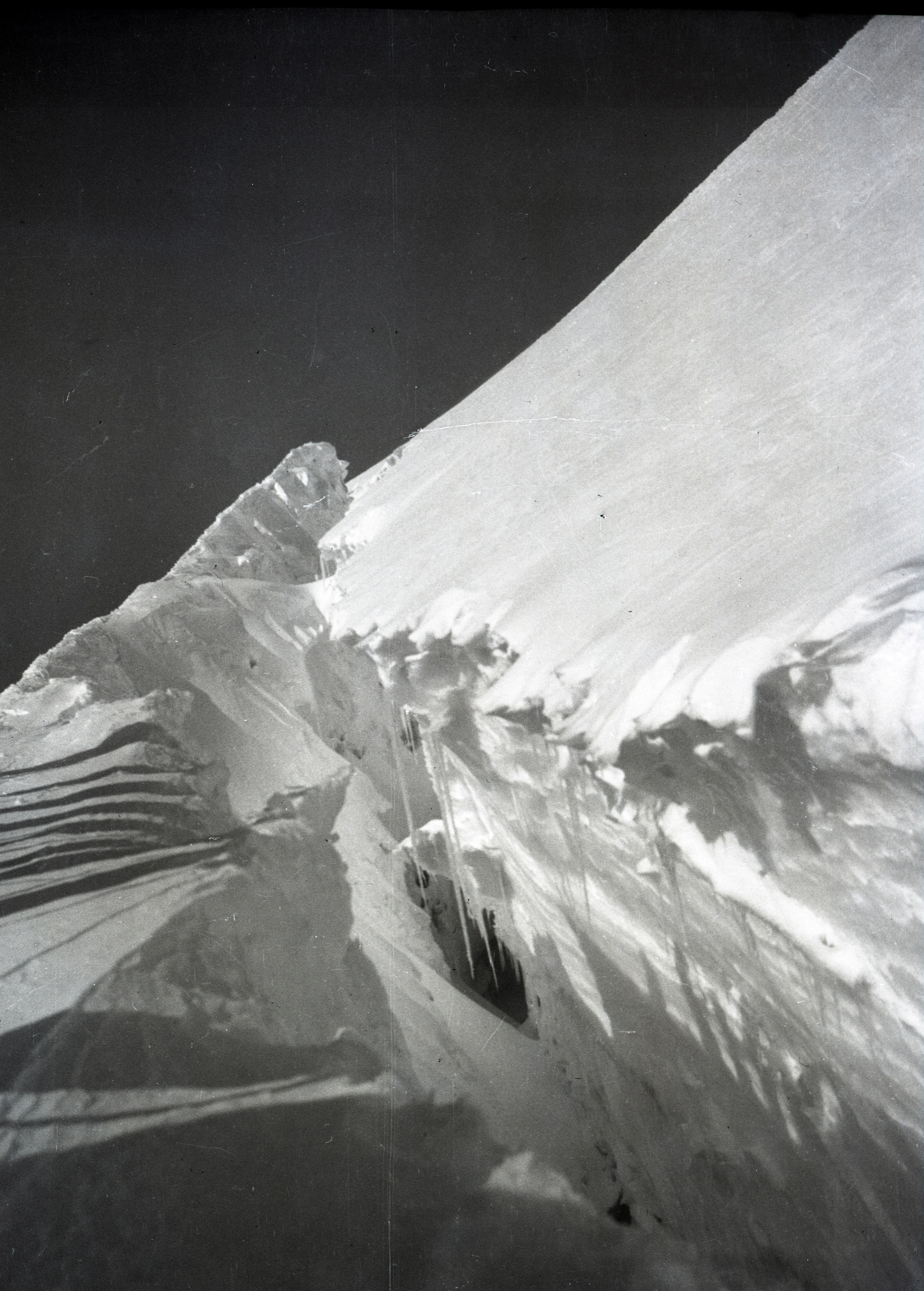

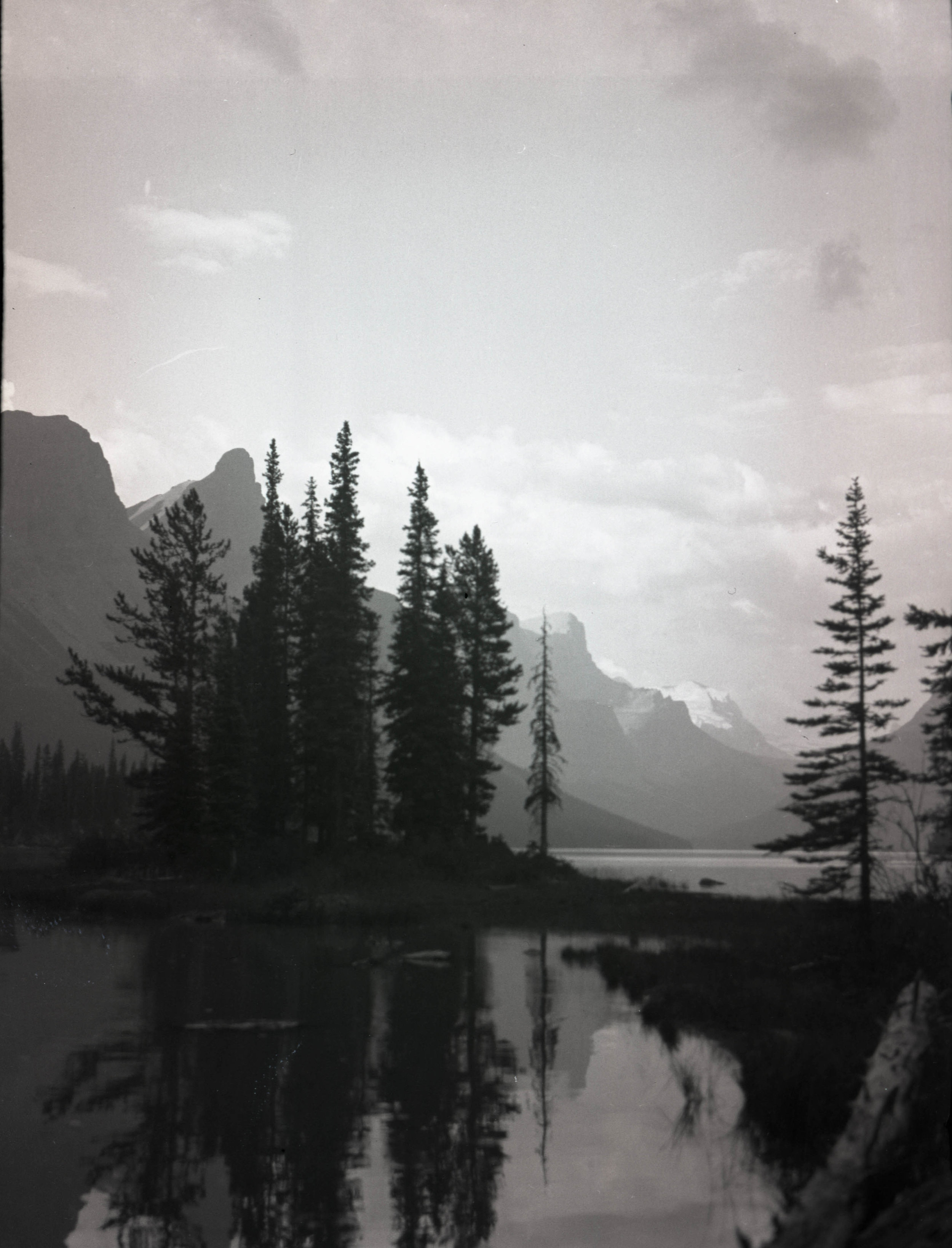

At the American Alpine Club Library, we’re very fortunate to have quite a few collections of photographs of climbing and mountaineering from the early 20th century. One of these, a collection of roughly 3000 photographic negatives dating from 1900 to about 1930, has been digitized in its entirety and made available to everyone.

It’s a great feeling to complete a project.

We’re excited to be able to increase access to this collection through digitization, which also reduces wear and tear on the original negatives and adds an additional layer of preservation.

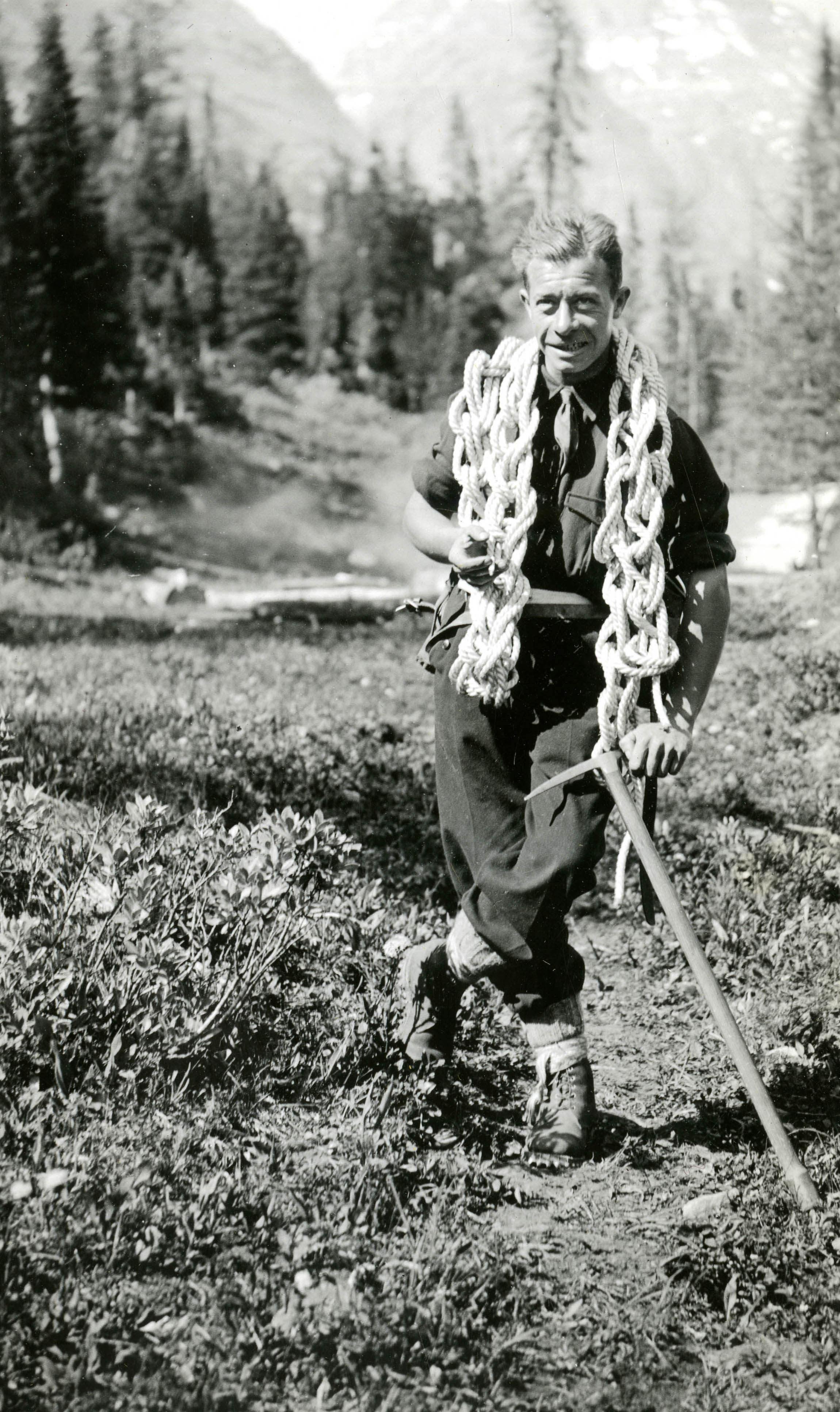

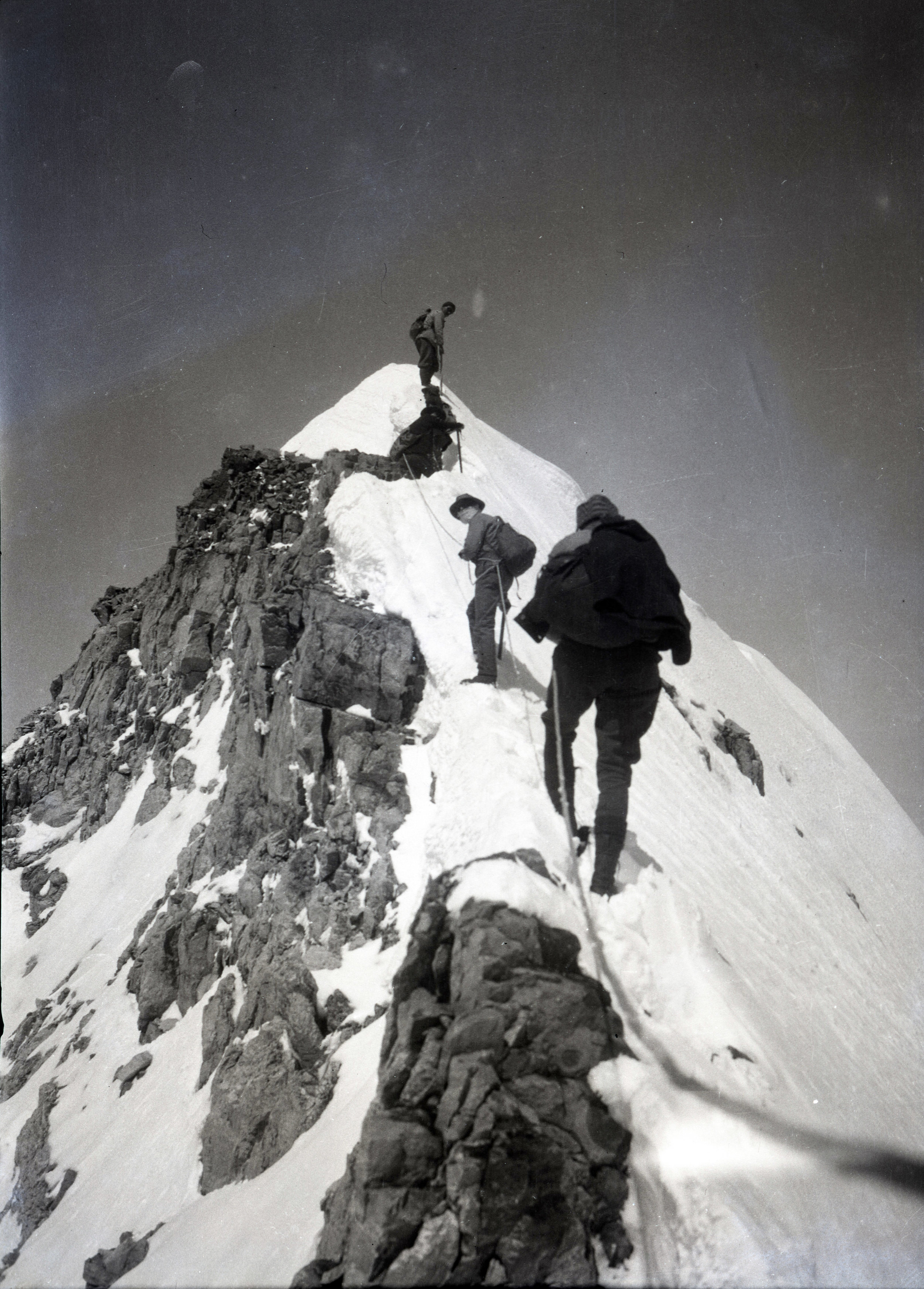

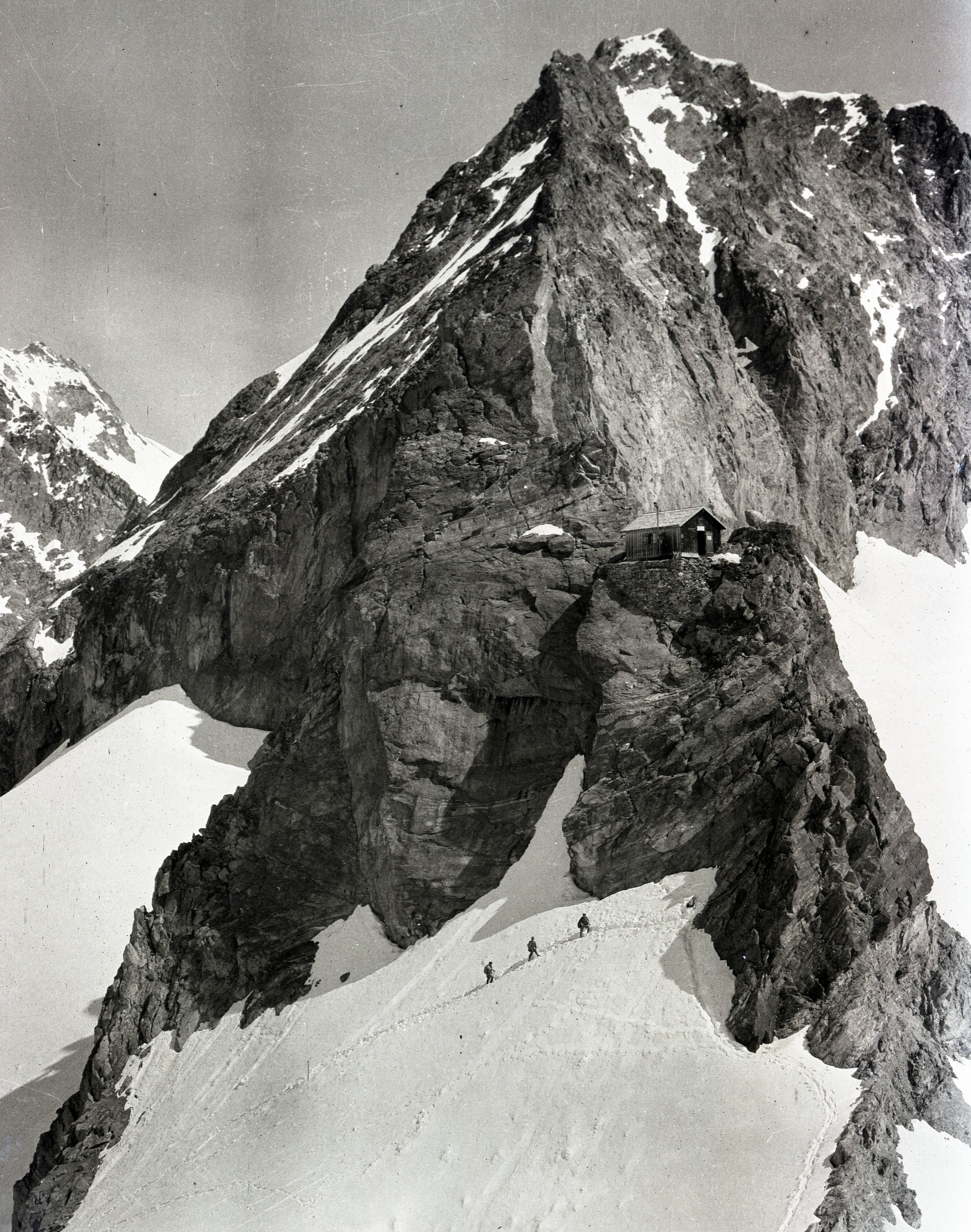

This collection of photos belonged to Andrew J. Gilmour, a dermatologist living and working in New York who was an avid climber and active member of the American Alpine Club during the 1920s and 1930s. He did a number of ascents in the Alps, the Canadian Rockies, the Cascades and the Western U.S., as well as Wales and the Lake District in the UK. His photos show us a lot about climbing at that time, the techniques, equipment, conditions and the people and places involved. It also provides us with a glimpse of what the world was like about 100 years ago.

We’ve gathered some of our favorite images from this collection in the slideshows below. Enjoy!

To see more of these images, check out our Andrew J. Gilmour album on Flickr.

Climbing and Mountaineering

Photos of climbing parties and mountaineering expeditions from about 1910 to the mid 1930’s.

Equipment

Hobnail boots, hemp rope, canvas and silk tents and men’s and women’s climbing attire.

Summits

Men and women on top

Camps and Huts

Huge camps for gatherings with the Alpine Club of Canada, tents and lean-tos in the woods, Swiss Alpine Club huts - many of which are still in use today.

Travel

It was harder in those days to get to some of these remote locations. There were far fewer roads, almost no highways and air travel was still in its infancy. Trains, ships and horses were commonly used.

Life and Times

The world has changed a lot since 1900 - these photos illustrate just a few of the differences.

Places

Some gorgeous photos of some famous locations as they used to be.

Check out our Flickr account for more! Or, to view all the photos, head to our archival collections site and scroll down to Collection Tree.

Suggested reading:

For details of mountaineering and climbing in the first decades of the 20th century, check out the handbook Mountain Craft by Geoffrey Winthrop Young.

For more about some of the places depicted in these photos:

Mount Rainier a Climbing Guide by Mike Gauthier

Cascades Rock the 160 Best Multipitch Climbs of all Grades by Blake Herrington

The North Cascades by William Dietrich

Mont Blanc the Finest Routes: rock, snow, ice and mixed by Philippe Batoux

Mont Blanc: 5 routes to the summit by Franȯis Damilano

Swiss Rock Granite Bregaglia: a selected rock climbing guide by Chris Mellor

Canadian Rock select climbs of the west by Kevin McLane

Sport climbs in the Canadian Rockies by John Marin and Jon Jones

Mixed Climbs in the Canadian Rockies by Sean Isaac

For more information about the person who took these photos, you can read Gilmour’s obituary in the American Alpine Journal.

The Secret History of the Ice Axe

For the Lady Mountaineer

Elizabeth Hawley 1923 – 2018

Elizabeth Hawley, known as the Chronicler of the Himalayas, kept meticulous records of climbs in the Nepalese Himalaya for over half a century. Those records make up the Himalayan Database. She was a remarkable woman and will be missed.

Miss Hawley has donated her archives to the American Alpine Club Library, where they will be preserved for future generations. Already residing in the archives are Miss Hawley's correspondence, postcard collection and the newly arrived 1963 American Everest File. Her files and personal library collection will arrive in the coming months.

Below you will find tributes from Lisa Choegyal, good friend of Miss Hawley, and Richard Salisbury, friend, co-author and builder of the Himalayan Database.

By Lisa Choegyal

Nepali Times

Elizabeth Hawley, who died in Kathmandu on 26 January 2018 aged 94 years, was an American journalist living in Nepal since 1960, regarded as the undisputed authority on mountaineering in Nepal. Born 9 November 1923 in Chicago, Illinois and educated at the University of Michigan, she was famed worldwide as a “one-woman mountaineering institution”, systematically compiling a detailed Himalayan database of expeditions still maintained today by her team of volunteers, and published by the American Alpine Club.

Respected for her astute political antennae and famously formidable, Miss Hawley represented Time Life then Reuters since 1960 as Nepal correspondent for 25 years. She is credited with mentoring reporters and setting journalistic standards in Nepal, competing to file stories from the communications-challenged Nepal of the 1960s. She worked with the pioneer adventure tourism operators, Tiger Tops, from its inception in 1965 with John Copeman, until she retired as AV Jim Edward’s trusted advisor in 2007.

For Sir Edmund Hillary, she managed the Himalayan Trust since it started in the mid-1960s, dispensing funds to build hospitals, schools, bridges, forest nurseries and scholarships for the people of the Everest region. Generations of Sherpas remember being overawed by the rigor of Miss Hawley’s interviews, and quake at the memory of her cross-examinations when collecting their scholarship funds. Sir Edmund Hillary described Elizabeth Hawley as “a most remarkable person” and “a woman of great courage and determination.” She served as New Zealand Honorary Consul to Nepal for 20 years until retiring in 2010.

Elizabeth first came to Nepal via India for a couple of weeks in February 1959. She was on a two-year round the world trip that took her to Eastern Europe, the Middle East and South Asia. Bored with her job as researcher-reporter with Fortune magazine in New York, she had cashed her savings to travel as long as they lasted. Nepal had been on her mind since reading a 1955 New York Times article about the first tourists who visited the then-Kingdom.

Because of her media contacts, the Time Life Delhi bureau chief asked her to report on Nepal’s politics. It was an interesting time - as one of only four foreign journalists, she was present when King Mahendra handed over the first parliamentary constitution, which paved the way for democracy in Nepal. Fascinated by Nepal’s politics and the idea of an isolated country emerging into the modern 20th century, she returned in 1960 and never left, living in the same Dilli Bazaar apartment, the same powder blue Volkswagen beetle car, and generations of faithful retainers.

A diminutive figure of slight build with a keen look, Elizabeth was bemused at the universal attention she received. Her Himalayan Database expedition records are trusted by mountaineers, newswires, scholars, and climbing publications worldwide, published by Richard Salisbury and the American Alpine Club. She was one of only 25 honorary members of the Alpine Club of London, and has been formally recognized by the New Zealand Alpine Club and the Nepal Mountaineering Association. In 2004 she received the Queen's Service Medal for Public Services for her work as New Zealand honorary consul and executive officer of Sir Edmund Hillary’s Himalayan Trust. She was awarded the King Albert I Memorial Foundation medal and was the first recipient of the Sagarmatha National Award from the Government of Nepal.

Elizabeth’s career in the collection of mountaineering data started by accident: “I’ve never climbed a mountain, or even done much trekking.” As part of her Reuters’ job, she began to report on mountaineering activities and in those pioneering days of first ascents and mountain exploration, there was strong media interest in Himalayan expeditions. She relied heavily on the knowledge of mountaineer Col Jimmy Roberts, founder of Mountain Travel.

Since 1963 she has met every expedition to the Nepal Himalaya both before and after their ascents, including those who climbed from Tibet. Her records contain detailed information about more than 20,000 ascents of about 460 Nepali peaks, including those that border with China and India. Over the course of some 7,000 expedition interviews, her research work has sparked and resolved controversies. Elizabeth has seen the Nepal mountaineering scene transformed from an exclusive club to a mainstream obsession.

Elizabeth did not suffer fools gladly. Though some mountaineers were intimidated by her interrogations - sometimes jokingly referred to as an expedition's "second summit," - serious alpinists greatly admired her. "If I need information about climbing 8,000-meter peaks, I used to go to her," says Italian climbing legend Reinhold Messner. Nepali trek operator and environmentalist Dawa Steven Sherpa underlines the point: "Although it's the authorities that should have been doing this, they're not as strict or accurate as Miss Hawley. One of her biggest contributions is keeping mountaineers honest."

Elizabeth applied her trademark scrupulous precision to summarizing the political and development events in Nepal in her monthly diary, published in 2015 in two volumes as “The Nepal Scene: Chronicles of Elizabeth Hawley 1988-2007”. They stand as a faithful and unique historical record of the extraordinary changes that took place in Nepal over nearly two decades.

Her enviable journalistic sources were based on long friendships with the political, panchayat and Rana elite. She had the confidence of a wide range of prominent Nepalis, and shared a hairdresser with the (then) Queen. Educated as an historian, Elizabeth regarded herself as a reporter not a writer, stringently recording Nepal’s political and mountaineering facts with minimal opinion or analysis. Although there is no disguising her liberal bent and her admiration for the force of democracy. Former American Ambassador Peter Bodde said, Elizabeth Hawley was one of Nepal’s “living treasures” and “her contribution to the depth of knowledge and understanding between Nepal and the US was immense.”

Elizabeth Hawley’s achievements have featured in many books and articles about Nepal, and her biography by Bernadette McDonald, I’ll Call You in Kathmandu, was published in 2005, then updated and reprinted as Keeper of the Mountains. In 2013, to mark the 60th anniversary of the first ascent of Everest, Elizabeth was featured in the award-winning US television documentary of the same name, produced by Allison Otto. On screen in Keeper of the Mountains, her straightforward manner and fearless modesty made her something of a cult classic. In 2014 the Nepal government named a 6,182 meters (20,330 feet) peak in honour of her contribution to mountaineering. Elizabeth was not impressed:

"I thought it was just a joke. Mountains should not be named after people."

Miss Elizabeth Hawley is the last of the first generation of foreigners who made their life in Nepal, single and determinedly independent. She is survived by her nephew Michael Hawley Leonard and has bequeathed her library and records to the American Alpine Club. As both a successful woman in a man’s world and a highly visible foreigner recording Nepal’s history, we are all in her debt. She defied the conventions of her time, and determined to live life on her own terms and in her own incomparable style.

Elizabeth Hawley and the Himilayan Database

Remembrance of Elizabeth Hawley from Richard Salisbury, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 4 February 2018

I first met Liz Hawley in 1991 as the leader of the American Annapurna IV expedition when she came to interview me at the Malla Hotel. She was armed with the results of all of the previous expeditions to Annapurna IV, while I had prepared a spreadsheet taken from past American Alpine Journals showing the arrival and summit dates of the previous teams in order to make an estimate of the amount of supplies that would be needed for the climb.

Given what we both had, I suggested to Liz that we collaborate on building a database for her records. Liz initially declined saying that she was already working with a Nepali computer student to do this. But a year later in 1992, she contacted me telling me that her student had run off to graduate school in Arkansas and probably would never return to Nepal.

Thus began a multi-year project to design and enter her records into the database that the American Alpine Club published in 2004 as the Himalayan Database. Over 10,000 hours were spent entering the vast amount of information Liz had collected and stored in her wall-to-wall cabinets since she met the first American Everest expedition in 1963.

When the database was published, I hoped that we might be able to continue updating for 4 or 5 years, as Liz was then 80 years old. But Liz continued to thrive and we kept going strong ever since keeping the database up-to-date with all of the new teams coming to Nepal. With Billi Bierling now at the helm, we expect to continue for many years into the future.

I feel blessed to have had such a wonderful working relationship with Liz for 25 years and will greatly miss seeing her when I again come to Kathmandu later this year.

Mountaineering Boots of the early 20th century

A tale of horror and woe

by Allison Albright

Modern mountaineering boots are made to be comfortable, lightweight, insulated and waterproof. They're constructed of nylon, polyester, Gore-Tex, Vibram and involve things like "micro-cellular thermal insulation" and "micro-perforated thermo-formable PE." This technology costs anywhere from a couple hundred dollars to over $1000 and makes it much more likely for a mountaineer to keep all their toes.

We didn't always have it so good.

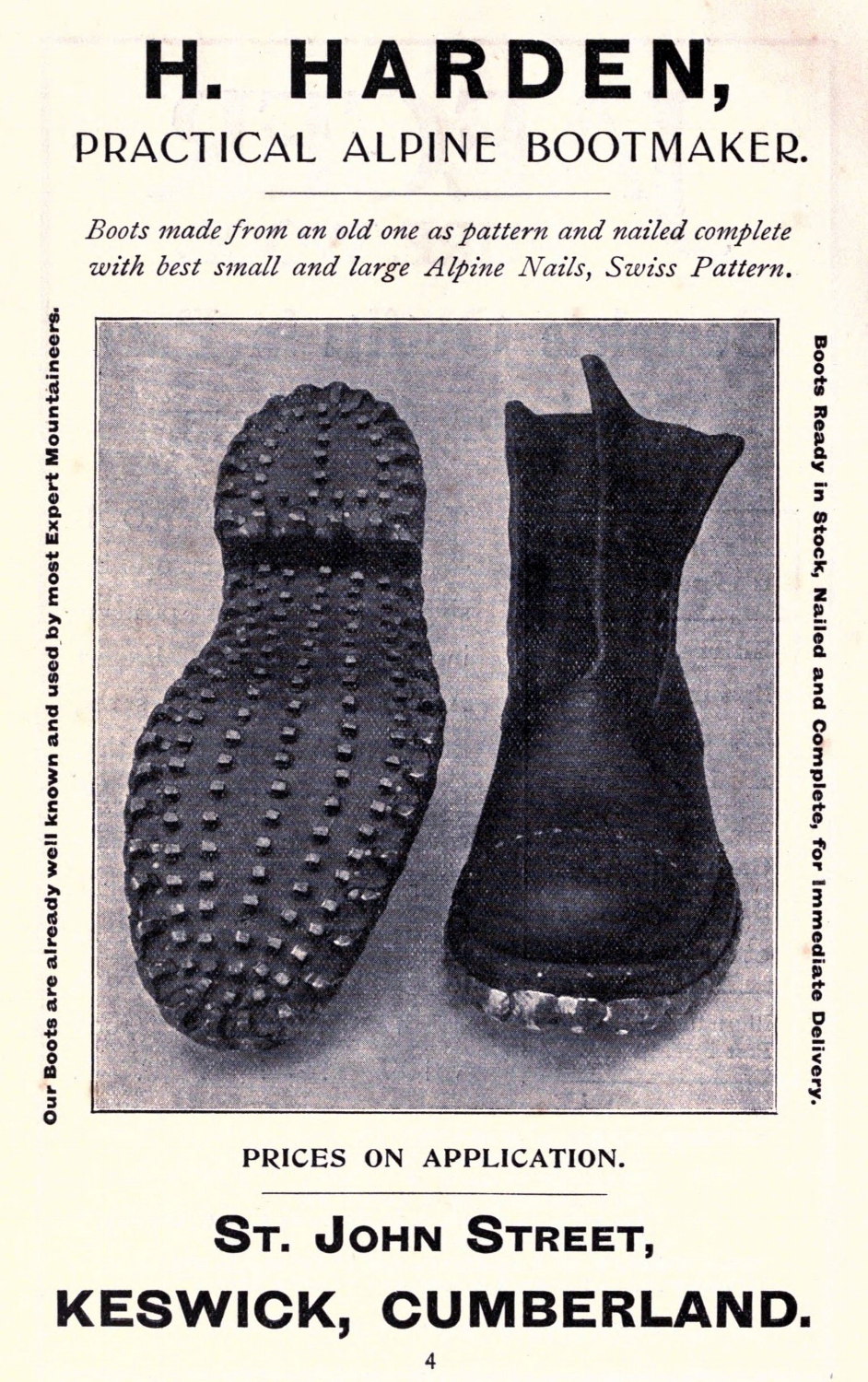

Mountaineering boots circa 1911.

By H. Harden - Jones, Owen Glynne Rock-climbing in the English Lake District, 1911, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=9433840

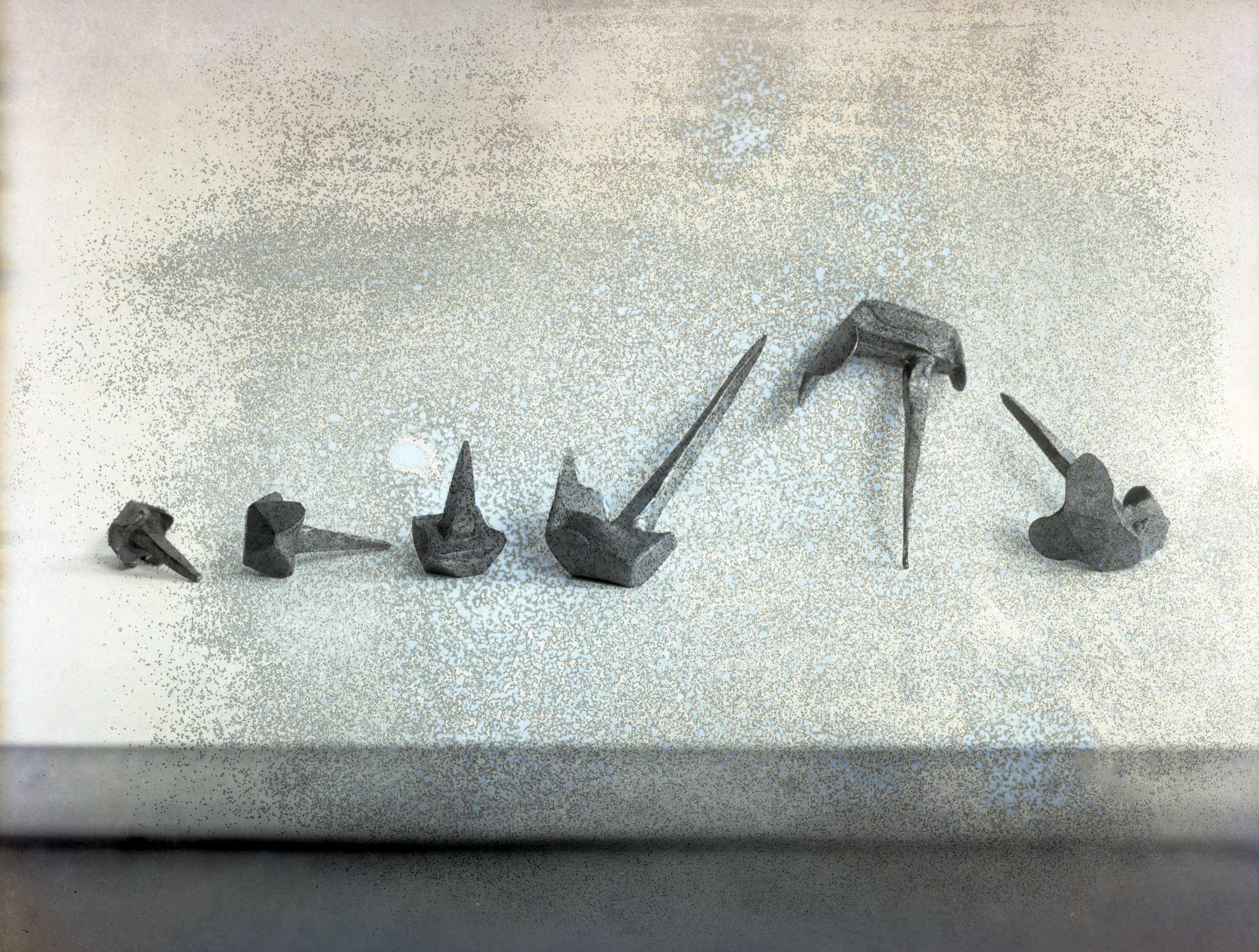

Early mountaineering boots were made of leather. They were heavy, and to make them suitable for alpinism it was necessary for climbers to add to their weight by pounding nails, called hobnails, into the soles.

“The very best boot is without a doubt the recognized Alpine climbing boot. Their soles are scientifically nailed on a pattern designed by men who understood their business; their edges are bucklered with steel like a Roman galley or a Viking’s sea-steed. No doubt they are heavy, but this slight inconvenience is forgotten as soon as the roads are left.”

Tricouni nails were a recent invention in 1920 and could be attached to mountaineering boots to provide traction. They were specially hardened to retain their shape and sharpness.

Illustration from Mountain Craft by Geoffrey Winthrop Young. New York, 1920.

Illustration of boot nails from Mountaineering Art by Harold Raeburn, 1920.

In 1920 a pair of climbing boots went for about £3.00 - the equivalent of $28.63 in 2017 US dollars. However, climbers got much less for their money than we get out of our modern boots.

Original hobnails, stored in a reused box

“There is no use asking for “waterproof” boots; you will not get them.”

In addition to being heavy, the boots were not waterproof. Mountaineers had to apply castor oil, collan or melted Vaseline to the boots before each trip. This kept the boots flexible and also kept at least some water out. Animal fats were also an option, but they had a strong, unpleasant smell and would decompose, causing the leather and stitching of the boots to rot as well.

Hobnail boots

in action on Mumm Peak, Canada. 1915

Photo from our Andrew James Gilmour collection.

Boots with linings were not recommended for mountaineering, as the linings were usually made of wool and other natural fibers which were slow to dry when inside a boot. Wet boot linings, either due to water or snow leakage or human sweat, were a major cause of frostbite resulting in the loss of toes.

When not in use, the boots needed to be stuffed with dry paper, hay, straw or oats which were changed at intervals to ensure that all moisture was absorbed. If they weren't stuffed in this manner on an expedition, they were in danger of freezing and twisting out of shape.

A pair of worn hobnail boots set to dry over a fan in about 1920. This luxurious set-up was possible because the mountaineer was staying in a Swiss hotel.

Photo from our Andrew James Gilmour collection.

“Look with suspicion upon the climber who says he wears the same pair of boots without re-soling for three or four years. It will probably be found that his climbing is not of much account, or he is wearing boots which have badly worn and blunted nails, with worn-out and nail-sick soles, a worse climbing crime if he proposes to join your party, than if he were to wander up the Weisshorn alone.”

Crampons

Today crampons are made of stainless steel and weigh about 1 to 2 lbs. They can be bolted or strapped to the boot. In the early 20th century, crampons were made of steel or iron. They were strapped to the boot with hemp or leather straps passed through metal loops attached to the frames. Surprisingly, they didn't weigh too much more in the 1920s than they do today.

They could be bought in a variety of configurations, including models ranging from four to ten spikes. Mountaineers who recommended their use wrote that good crampons should have no fewer than eight spikes which should not be riveted to the frame. The crampons also should not be welded anywhere and the iron variety were likely to break if any real work were required of them.

A steel crampon with eight spikes and hemp and leather straps - ideal!

From the American Alpine Club Library archives

Good footwear is still one of the most important aspects of any trip. We're extremely grateful boot technology has advanced so much.

Care and Handling of Archival Nitrate Negatives

by Allison Albright

Nitrate film base was developed in the 1880s and was the first plasticized film base available commercially. It enabled photographers to take pictures under more diverse conditions, and its flexibility and low cost was partially responsible for making photography affordable and accessible to amateur consumers as well as professionals. It was widely used from the 1890s until the 1950s.

An album of nitrate negatives circa 1900

Nitrate negatives also happen to be mildly toxic and somewhat volatile. Because the material is the same chemical composition as cellulose nitrate (also known as flash paper or guncotton), which is used in munitions and explosives, it is incredibly flammable and prone to auto-ignition. It was also used in motion picture film in the early 20th century and was responsible for several movie theater fires during that era.

Below are some negatives in the early stages of deterioration.

As if the danger of combustion wasn’t enough, nitrate negatives also emit harmful nitric acid gas as they deteriorate, meaning that we need to use safety precautions such as respirators and latex gloves when handling these negatives.

HNO3 + 2 H2SO4 ⇌ NO2+ + H3O+ + 2HSO4

Nitric acid is considered a highly corrosive mineral acid.

Nitrate negatives usually deteriorate in just a few decades, making them an extremely unstable storage medium. As they deteriorate, the image begins to fade and the negative turns soft and gooey, causing it to weld itself to whatever it’s stored with, resulting in the loss of the image.

A clump of badly deteriorated negatives stuck together forever

When good negatives go bad - a negative in the process of becoming goo

Like most archival collections containing materials created from about 1890 to the early 1950s, the AAC’s collection includes some nitrate film negatives. For most of their lives, these negatives have been stored in a cold, temperature controlled area. We’re digitizing these negatives in order to capture the images and make them accessible to the public before we put them in deep freeze. The best way to preserve and store nitrate negatives for the long term is to freeze them to slow the process of deterioration and minimize the risk that they’ll start a fire.

Because of the unstable nature of nitrate negatives, some deterioration is to be expected. However, the vast majority of this collection is still in good shape. We've included a few selections below. Eventually, we’ll make all the images from our nitrate negatives available.

These photographs are taken from the collection of Andrew James Gilmour (1871-1941), an AAC member whose surviving photographs help inform our knowledge of the history of climbing and what the sport was like in the early 20th century.