The west face of Seerdengpu, a towering rocky summit of 5,592 meters in China’s Siguniang National Park, had been attempted at least a dozen times without success. Among others, West Virginia climber Pat Goodman tried six different lines during three separate expeditions. In 2024, a Chinese climber finally topped out on the 850-meter face, in his fourth year of attempts. Unable to secure a permit, he climbed alone and in secret in August 2024, completing only the second known ascent of the peak. Below is his story.

SEERDENGPU, WEST FACE

The west face of Seerdengpu (5,592m), approximately 850 meters high. Prior to 2024, the peak had only been climbed once, in 2010, by Americans Dylan Johnson and Chad Kellogg. The west face had been attempted at least a dozen times without success. Photo: Griff.

In 2015, when I first saw Seerdengpu (5,592m) from the west, I never thought that one day I would stand on the summit. The ca 850m west face was one of the great unclimbed walls of Siguniang National Park and had been attempted many times, notably by American Pat Goodman. In 2013, with Matt McCormick, he made unsuccessful attempts on three different lines, then later another attempt with Marcus Costa, and another, more toward the southwest, with David Sharratt. Costa made another attempt with Enzo Oddo. The face had also been tried by Russian, Australian, Polish, and Chinese teams. Loose terrain and objective danger appear to have been a common problem.

Until 2024, Seerdengpu had only one ascent. In 2010, Dylan Johnson and Chad Kellogg (both USA) climbed the northeast ridge (see note below). Prior to their ascent, four parties had attempted the north face.

I first tried the west face in August 2021 but chose a poor line and retreated after 80 meters. In 2022, I changed to the previously attempted line on the right side of the wall (the line attempted by Costa and Goodman, as well as the Russian and Chinese teams). I retreated after 350 meters. Over three weeks in July 2023, I only reached 200 meters up the same line. I returned in August 2024.

Unable to get an official permit, I had to work alone, as porters did not dare provide service. [Because of this, the author is using an alias.] I entered the valley several times as a tourist, each time carrying a 40-liter bag. In the end, I ferried a total of 75kg of equipment from the road in Shuangqiao Valley to my base camp at 4,500 meters.

French climber Enzo Oddo in the ice gully on the west face of Seerdengpu in January 2015. Oddo and Marcos Costa attempted a winter ascent, hoping to avoid the rockfall danger that plagued other attempts. The ice was excellent, but two-thirds of the face still involved hazardous rock climbing. The successful 2024 ascent followed the same gully in August. Photo: Marcos Costa.

After the initial 170 meters of the face, which is 5.7, the route enters a gully. It is always wet. Some previous attempts had failed due to the volume of water, and in 2015 Costa and Oddo tried this route in January, finding the gully nicely frozen but the rock above dangerously loose. They retreated from the Russian high point. I kept mostly in the bed of the narrow gully, which was wet and loose, but easier (5.8 C1+). I made my first portaledge camp at the top of the gully at around 5,100 meters.

On the first day above the portaledge, I climbed 80 meters at 5.9 C1+. When I rappelled to the ledge that evening, I found two holes in the fly, one of them large. A small bag on the ledge had also been hit and damaged. The next day, I climbed up left on loose but easy rock (5.6), found a site for my next camp, and spent all the following day moving my equipment to Camp 2 (5,250m).

On August 24, I aided a horizontal crack and took the only fall of the route. I retreated and took a different line, a corner with a thin crack that evolved into a chimney. It was a brilliant 60m pitch at 5.9+ C2. (I suspect it would go free at 5.11 or 5.11+.) Above this, I traversed left using all my 70m rope, then went back to the portaledge for the night. I found it difficult to sleep due to the cold, and perhaps the excitement of being close to the top.

On the 25th, I regained my high point and continued up at 5.8 C1+. That day I dropped an ascender, a Camalot, and a sling. I realized that I was losing concentration and needed to be more careful. That night, I didn’t get to sleep until 3 a.m. I was sick and cold. I left Camp 2 again at 8 a.m. on August 26—a total of 27 days since I first started ferrying loads from the road. I reached my high point at 11 a.m. and climbed for a further 150 meters to the top of the face. From there I walked 200 meters over ice and boulders to reach the highest point of the mountain, at 2:55 p.m., for its second ascent.

Close-up view of the first ascent of the west face of Seerdengpu. The wall is about 850 meters high, and the climbing distance of the route totaled about 1,200 meters. Photo: Griff.

Unfortunately, just 50 meters before reaching the summit, a loose boulder fell onto my left foot and broke a toe. As I started back down, it began to rain. Four hours of rappelling through rain and sleet took me back to the portaledge. My foot was painful and didn’t look good, so I decided I should get off the mountain the next day and called friends to let them know.

On the 27th, I threw some gear and the portaledge off the wall and rappelled from 11:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., reaching base camp that day. A few days later I was in a Beijing hospital, having an operation on my toe. My friends later collected my gear from base camp.

I named the route Wild Child. It has around 1,200 meters of climbing up to 5.9+ C2. I did not carry a bolt kit, but there are five bolts in the initial gully, all installed by a 2014 Chinese team for rappel anchors. Higher, there is one bolt at Camp 1, thought to have been installed by the Russian team.

—Ma Fang, China

Editor’s Note: Because he climbed without a permit, the author of this report used a pseudonym for his AAJ story.

Only a Few Days Left—Get the Shirt

The American Alpine Journal is one climbing’s most historic and treasured publications. Get it with your American Alpine Club Membership! For the month of June only, also get the limited edition t-shirt!

Already a member? Donate $30 or renew in the month of June!

Use promo code: DIRTBAG

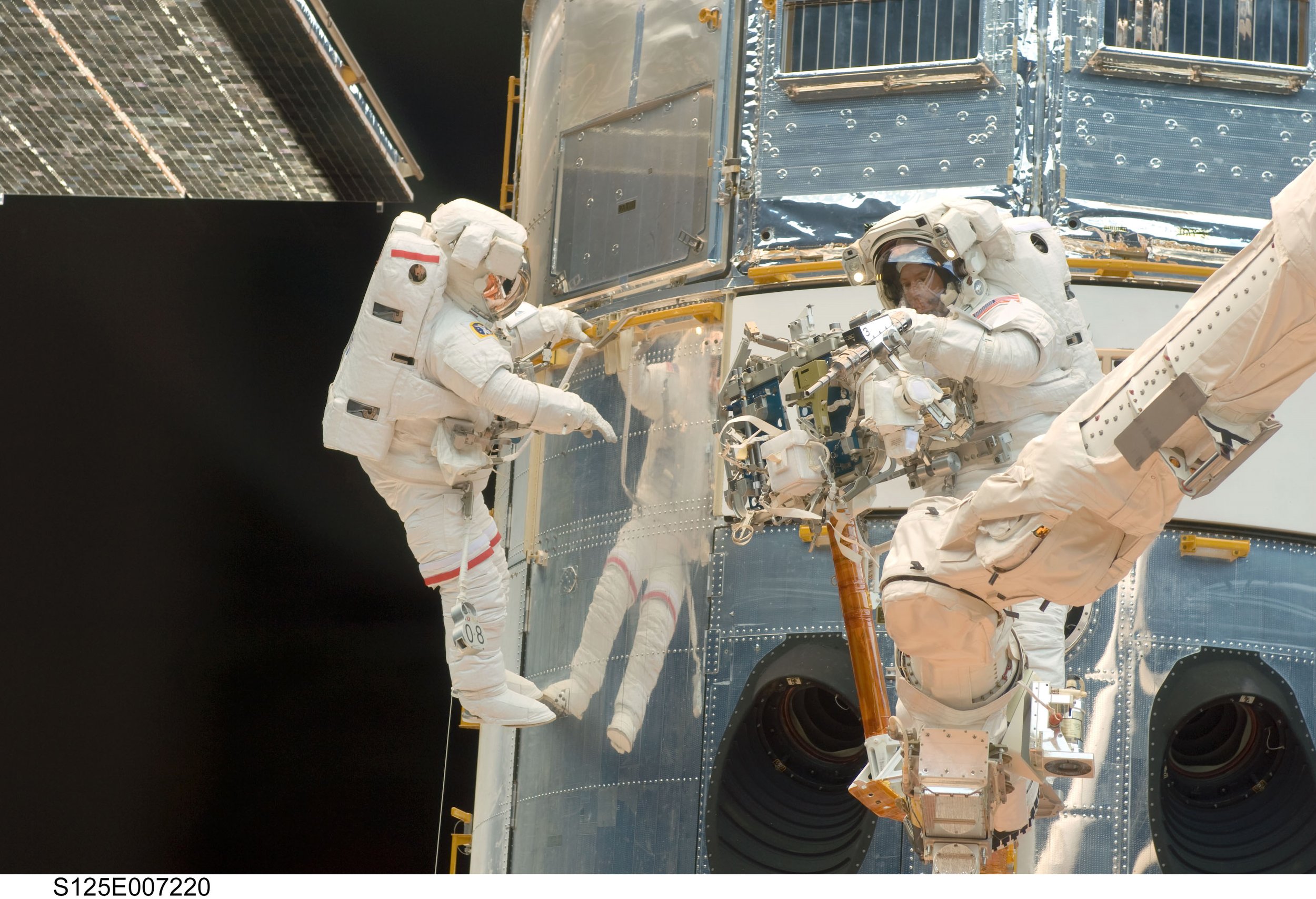

SEERDENGPU: THE FIRST ASCENT

Seerdengpu from the north, with the line of the first ascent by the northeast ridge (mostly hidden). The "nose", unsuccessfully attempted by several teams, divides shadow and sunlight. The west face, climbed in 2024 for the mountain’s second ascent, is partially in view to the right. Photo: Dylan Johnson.

American climbers Dylan Johnson and Chad Kellogg made the first ascent of Seerdengpu in 2010, two years after climbing a new route up nearby Siguniang. On their third attempt in 2010, the pair climbed the northeast ridge of Seerdengpu in a 34-hour round-trip push from their high camp. It was Johnson’s third summit in the Qionglai Mountains and Kellogg’s seventh. Tragically, Kellogg died less than four years later in a rockfall accident in Patagonia. Johnson’s report about the Seerdengpu climb appeared in AAJ 2011: Read it here.

Powered by:

Supported by:

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), powered by Arc’teryx, with additional support from Mountain Project by onX. The line is emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Got a potential story for the AAJ? Email the editors at aaj@americanalpineclub.org.