The Line is the monthly newsletter of the American Alpine Journal.

Vitaliy Musiyenko following pitch six (5.11), one of the cruxes of Against the Grain on Charlotte Dome. Photo by Brian Prince.

THE BEST 5.11 IN THE HIGH SIERRA?

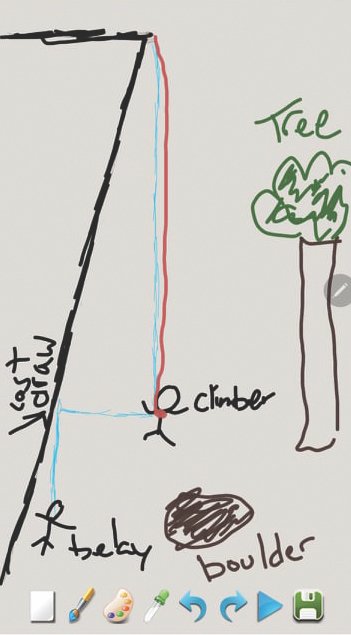

“Over the last couple of years, I’ve been working on a route which, in my honest opinion, has the potential to become known as one of the five best 5.11s in the High Sierra.” That’s the start of Vitaliy Musiyenko’s report for AAJ 2023 on Against the Grain, a new route up Charlotte Dome in California’s Kings Canyon National Park. Musiyenko, co-author of the new High Sierra Climbing guidebooks, and Brian Prince completed the 1,800-foot 5.11c route in late July of 2022.

“I had just developed COVID symptoms on the day we hiked into camp at Charlotte Lake,” Prince wrote in an email, recalling the first ascent. “The next day, when we climbed the route, I was really pretty wrecked. I think the only way I was able to keep climbing was that the route was so good. I put on a mask at the belays to try and protect Vitaliy, but he ended up testing positive a few days later anyway. It says a lot about Vitaliy that he didn't hate me for giving him COVID when he avoided it after working through the height of the pandemic in an emergency room.”

Against the Grain has about 1,800 feet of climbing on the southeast face of Charlotte Dome. The “Fifty Classics” South Face route ascends the corrugated face to the left. Photo by Vitaliy Musiyenko.

Prince added, “I just felt grateful that Vitaliy asked me to join him to climb the route after he put so much work into it. It felt like a kind of peak in our partnership because he would be moving out of California [to Utah] soon after.”

Against the Grain takes a direct line up the southeast face of Charlotte Dome, well to the right of the classic South Face route (Beckey-Jones-Rowell, 1970), and also to the right of Dance of Dragons, a route that Musiyenko established in 2017 with Jeremy Ross. Curious about the claim that the new route might be among the best 5.11s in the High Sierra, we asked Musiyenko and Prince—two of the Sierra’s most active first ascensionists—to fill out their top five. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they agreed on most of the climbs. Here’s their list in alphabetical order:

Against the Grain (Charlotte Dome) • Friends (Spring Lake Wall) • Positive Vibrations (The Hulk) • Tradewinds (The Hulk) • Valkyrie (Angel Wings)

Prince also mentioned Sky Pilot on Mt. Goode and Sword in the Stone on Mt. Chamberlin, but added that he hadn’t done the latter. He said the new route on Charlotte Dome might be the best of them all: “Not just the top five…. It is vertical face climbing on a backcountry granite dome for pitch after pitch. There's just nothing else like it.“

Do you have a favorite long 5.11 in the High Sierra that ought to be on this list? Name it in the comments below.

The south side of Cerro Iorana at sunset. Photo by Andrew Opila.

THE WILDS OF TIERRA DEL FUEGO

In a “Recon” article for AAJ 2020, geographer and exploratory climber Camilo Rada described the history and climbing possibilities in the remote Cordillera Darwin of Tierra del Fuego, at the southern tip of South America. Inspired in part by this article, Spanish climbers Eñaut Izagirre and Ibai Rico organized an expedition to the Cordillera Darwin in 2022 to attempt unclimbed peaks and study the snow and glacier dynamics in the range. With a base camp aboard the yacht Kotik, the seven-person expedition found great success, making the first ascents of the central summit of Monte Roncagli and Cerro Sara, as well as a new variation on Monte Francis. The team also collected snow samples from extremely remote sites and recovered thermometers and recording devices placed by Izagirre during a previous expedition in 2018. Among the early findings: The Roncagli (Alemania) Glacier has retreated at the alarming rate of more than a kilometer in just four years.

Izagirre and Rico’s article about the expedition will appear in AAJ 2023, which will be mailed to AAC members at the end of this summer. In the meantime, here’s a gallery of the team’s photos from the wild and beautiful Cordillera Darwin.

Photographer and climber Andrew Opila has produced a 30-minute film about the expedition, Into The Ice, which premiered in Bilbao, Spain, and was shown at the Wasatch Film Festival in April. More festival dates are pending. See the trailer here.

THE CUTTING EDGE IS BACK!

Season five of the AAJ’s Cutting Edge podcast kicks off with an interview featuring Jackson Marvell, the 27-year-old alpinist from Utah who just climbed his second new route up the mile-high east face of Mt. Dickey in Alaska. Listen here or wherever you get your podcasts.

The Line is the newsletter of the American Alpine Journal (AAJ), emailed to more than 80,000 climbers each month. Find the archive of past editions here. Interested in supporting this online publication? Contact Billy Dixon for opportunities. Questions or suggestions? Email us: aaj@americanalpineclub.org.