By Mike Poborsky, UIAGM/IFMGA

Graphics By Rick Weber

This article was originally printed in the 2013 edition of Accidents in North American Climbing.

Lowering a climbing partner is among the most common situations leading to injuries and rescues reported in Accidents in North American Mountaineering, whether it’s lowering a climber after she tops out on a sport route or a partner in difficulty on a multi-pitch climb. In this year’s (2013) Know the Ropes section, we will look at common causes of accidents related to lowering, and provide some best practices for preventing them.

Why is it so important to have a good understanding of lowering skills and techniques? Think about how often we lower a climbing partner. We all do it frequently in single-pitch climbing, whether top-roping, gym climbing, or lowering the leader after he finishes a sport, ice, or traditional route. We tend to emphasize the belaying aspect of these activities, when in fact data shows there is substantial risk of an accident occurring during the lowering phase. Think about it in these terms: If all goes well during the climb, we don’t even use the safety systems in place. They are simply there “just in case” the climber falls. Once the lowering process starts, however, every component in the system engages and is critical to the safety of the climber. Then, of course, there are unlimited scenarios in multi-pitch climbing—whether rock, alpine, or ice—where lowering can be an effective tool to increase the speed of the party or to help a frightened or incapacitated partner.

Based on the incidents reported in Accidents over the past decade, the four most common causes of lowering accidents are: a rope that’s too short, miscommunication, an inadequate belay, and anchor failure. We’ll look at each of these issues and provide basic and advanced skills and techniques to address some of these common problems. Regardless of whether we are lowering from below or above, or are in single or multi-pitch terrain, many of the same skills and techniques are required.

Rope Too Short

More than half of all lowering accidents reported in Accidents in the past decade occurred when the rope end shot through a belay device and the climber fell uncontrollably. It is very easy to misjudge the length of your rope and/or the height of the anchor in vertical terrain. However, most of these unfortunate accidents could have been prevented simply by closing the system. This will make it impossible for the rope to unintentionally pass through the belay device.

FIGURE 1: The triple overhand knot is an excellent stopper knot for the end of a belay rope or rappel ropes.

In a typical single-pitch climbing scenario, where the pitch length is less than half the available rope, the ground closes the system by default, meaning your partner is going to make it back to the ground before the belayer gets to the end of the rope, so closing the system is unnecessary. The problem comes when the anchor is near or above the midpoint of the typical rope. This is increasingly common as new routes are established with anchors above 30 meters (half the typical modern rope length). For some climbs, a 70-meter rope is now mandatory to lower safely. Before trying an unfamiliar single-pitch route, read the guidebook carefully, ask nearby climbers, and/or research the climb online to be sure it doesn’t require a 70-meter rope to descend safely. When in doubt, bring a longer rope or trail a second rope.

Another scenario frequently leading to single-pitch lowering accidents is a climb where the difficulties begin after scrambling five or ten feet to a high starting ledge. The anchors at the top of such routes may be set in such a way that there is plenty of rope to lower the climber back to the ledge, but not all the way to the ground. Or the belayer may need to be positioned on the starting ledge in order to have enough rope to lower the climber safely. Again, do your homework, ask other climbers, and always watch the end of the rope as you’re lowering a partner.

If there is any doubt about the length of the rope being adequate to lower a climber safely, tie a bulky stopper knot in the free end so it cannot slip through the belay device. (The triple overhand knot is a good choice; see Figure 1.) Better yet, the belayer can tie into the free end, thus closing the system.

As you belay a lead climber on a long pitch, keep a close eye out for the middle mark so you’re aware of whether there is enough rope to lower the climber. Once the middle of the rope passes through your belay device, you and the climber need to be on high alert. Rope stretch may provide a little extra room for the climber to be safely lowered to the ground, but in such cases the system should always be closed as discussed above. When in doubt, the climber should call for another rope and rappel with two ropes.

As the climber lowers, it’s natural to keep an eye on her, but as the belayer you should also be watching the pile of free rope on the ground. Once there is less than 10 or 15 feet remaining, make a contingency plan for safely completing the lower. For example, will the climber have to stop on a ledge and downclimb? Will you need to move closer to the start of the route? Never let the last bit of rope slip through the device if the climber is still lowering, even if she is only a foot or two off the ground—the sudden release of tension can lead to a free fall and tumble.

When lowering in the multi-pitch environment, the belay system must be consciously closed by having the non-load end of the rope tied to the belayer, the anchor, or something else to prevent it from passing through the belay device. In a multi-pitch rappelling scenario we close the system by knotting the ends of the rappel ropes, making it impossible to rappel off the ends.

Miscommunication

The three key problems with communication between climber and belayer are 1) environmental, 2) unclear understanding of command language, and 3) unclear understanding of the intentions of the belayer and climber.

Environmental problems include the climber and belayer being unable to see each other because of the configuration of the route and/or the distance between the two; weather conditions such as wind, snow, or rain; and extraneous noises, such as a river, traffic, or other climbers shouting commands or chatting nearby.

In popular climbing areas with many parties on routes near each other, climbers sometimes mistake a command from a nearby party as coming from their partner. It’s always a good practice to use each other’s names with key commands: “Off belay, Fred!” or “Take, Jane!” When one climber is at the top of a single-pitch climb and rigging the anchor for a lower-off, top-rope, or rappel, it can sometimes be helpful for the belayer to step back temporarily so he can see his partner at the anchor and improve communication. When the climber is ready to lower, the belayer can move back to the base of the climb to be ideally positioned for the lower.

Especially with a new or unfamiliar partner, it’s essential to agree on the terms you’ll be using to communicate when one climber reaches the anchor. What do you mean by “take” or “off” or “got me?” Avoid vague language like “I’m good” or “OK.” Agree on simple, clear terms and use them consistently. One common misunderstanding seems to be the result of the similar sounds of “slack” and “take.” When top-roping, consider using the traditional term “up rope” instead of “take” for more tension in the rope, as the former won’t be confused with “slack.”

Before starting up any single-pitch climb, it’s critical that belayer and climber each understand what the other person will do when the climber reaches the anchor: Will the climber lower off, and if so what language will she use to communicate with the belayer? Or, will she clip directly to the anchor, go off belay, and rappel down the route? Many accidents have resulted when the belayer assumed the climber was going to rappel instead of lower, or the belayer forgot that the climber planned to lower, or he misunderstood a command (“off” or “safe” or “I’m in direct”) as an intention to rappel. Before taking the climber off belay, the belayer must be certain that this is the climber’s intention. If you have agreed that the climber will rappel, wait for the climber to yell “off belay,” and then respond “belay off,” and only then remove the rope from your device.

When you reach the anchor at the top of a climb, don’t just clip in, shout “take,” and lean back. Make sure to hear a response from the belayer indicating that he has you on belay and is ready to lower. If you can’t see the belayer, sometimes it is possible to extend your anchor connection or lower yourself a little, holding onto the “up” rope, until you can get into position to make visual contact with the belayer and assure you’re still on belay.

A consideration when lowering someone from above is that the belayer and climber become farther apart during the lowering process, and this may compromise communication. To mitigate this potential problem, I like to position myself where I can see, and hopefully hear, the climber being lowered from start to finish. In some terrain this requires extending the anchor’s master point.

Belay System Errors

A common cause of lowering accidents is belayer errors, especially when the belayer is inexperienced, inattentive, or unfamiliar with the operation of a particular type of device. Make sure your belayer—or any belayer you observe— knows what he’s doing and pays attention until his climber is safely back on the ground or at an anchor. Don’t accept or ignore shoddy belaying!

On single-pitch routes, two things that may cause problems are belayers positioned too far back from the base of the climb—and thus getting pulled off balance and possibly losing control when the climber weights the rope—as well as using an unfamiliar device. Switching between tube-style devices, such as an ATC, and assisted-braking devices like the Grigri can cause inexperienced belayers to mishandle the device. Beware of loaning your device to a belayer unless you are confident that he is well-trained in its use.

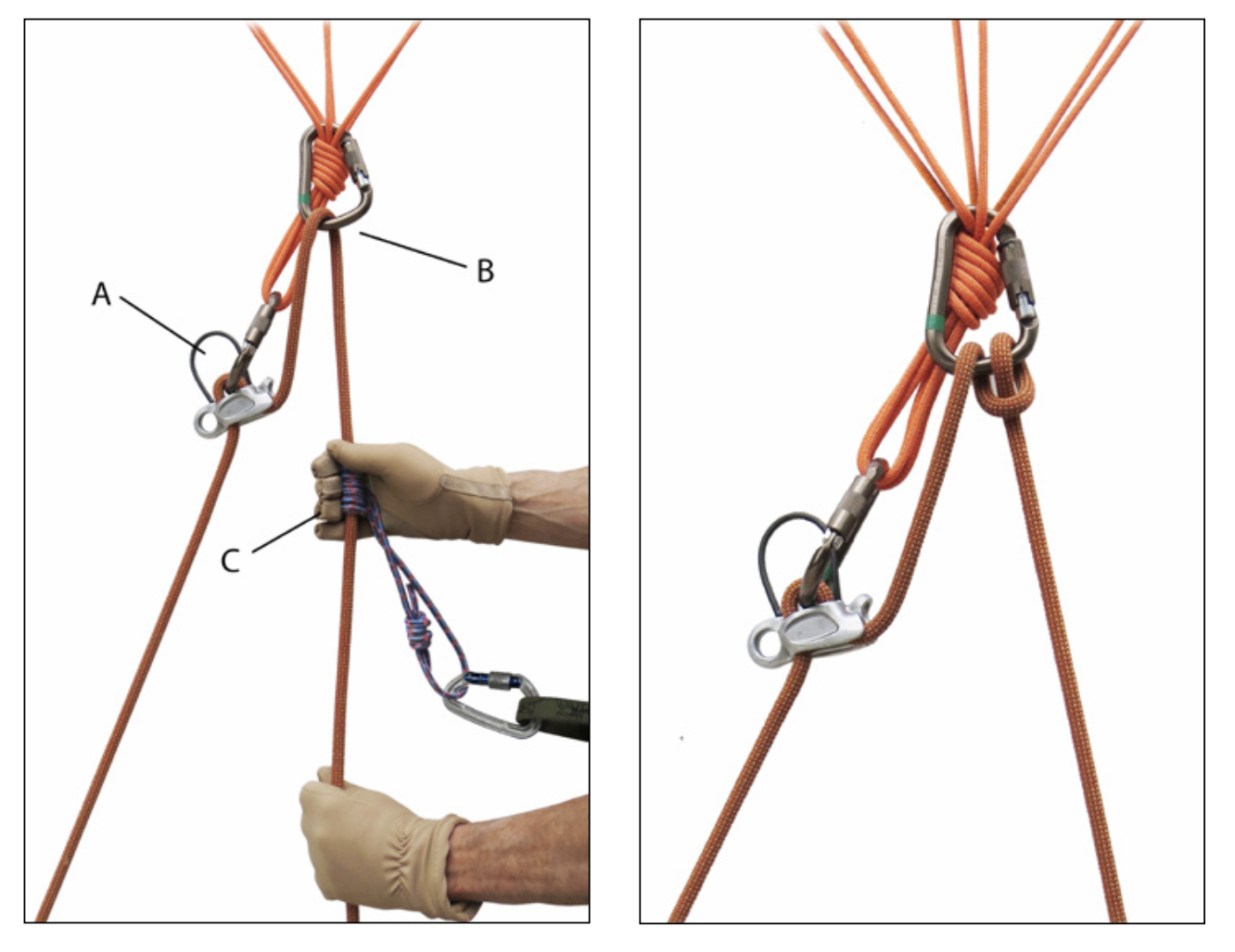

What is the appropriate lowering brake for lowering your partner? It’s one that provides adequate friction to control their descent over very specific terrain. In some alpine terrain situations, the redirected hip belay may be totally sufficient for a short, moderate-angle step with high friction. Conversely, lowering directly off an equalized multi-point anchor with a backup may be required in steeper terrain (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2: Lowering a partner from above with a redirect and backup. A) Belay/ rappel device with locking carabiner clipped to master point. B) Redirect through carabiner clipped to anchor. C) Prusik knot clipped to belay loop as backup—useful for heavier partners or wet or icy ropes.

FIGURE 3: Increasing friction for a lower with a thin-diameter or wet or icy rope, using a Munter hitch on a locking carabiner clipped to the anchor above the belay/rappel device.

In some cases, the most important belay issue may be anchoring the belayer against a violent upward pull in the event of a leader fall or a falling or lowering top-rope climber who is much heavier. In this situation I like to be tied directly into the climbing rope and use a clove hitch to attach myself to a bottom anchor. This way the length is adjustable so I can be exactly where I want with no slack in the system, and the rope provides shock adsorption if the system becomes loaded.

Most people tend to underestimate how much friction is needed to lower their partner in a safe and controlled manner. How do we gain the experience required to be safe? Through time and practice in varied terrain. Be conservative at first and anchor the belayer, increase friction, use a backup—or all three—until the belayer has confidence in judging how much friction is needed. It’s easy to back up a new climber’s belay by holding the brake strand a couple of feet beyond the belayer and feeding the necessary slack. This allows you to closely monitor the belay and provide additional braking if the climber starts going too fast or the belayer starts losing control.

Do you have experience lowering with wet or icy ropes? Do you have experience lowering with modern small-diameter ropes? If not, then I would recommend increasing friction when lowering someone from above (see Figure 3), as well as backing up the lower with a prusik, until you gain adequate experience. Bottom line: If the consequence of losing control of the brake strand is bad, add friction and back it up.

Prior to committing to any lower, consider some “what ifs.” For example, what if something happens when I’m lowering my partner and I need to be mobile? How easy is it for me to escape the system? What if I need to transfer this lower to a raise? Does this system allow me to make this transition easily?

Anchoring Issues

There is much to consider when constructing an anchor, but the bottom line is that it absolutely must not fail, period. (The Know the Ropes article in the 2012 Accidents is a great reference on constructing anchors.) What are some of my concerns when choosing a possible anchor? 1) Will I be using this anchor for climbing and lowering or rappelling? 2) With the resources available, can I construct an adequate anchor in a given spot? 3) How will the rope run once lowering starts? 4) Will the belayer and climber being lowered have visual and/ or audio communication for the duration of the lower?

I have long used the ERNEST acronym as guidance when constructing an anchor. E = Are all pieces in the anchor equalized and sharing the load? R= Is there redundancy in the anchor, meaning that if one piece fails other pieces will take the load? NE= If one piece does fail and the other pieces take the load, will this be done with no extension or shock loading of the remaining anchor? S= Is the anchor material (tree, rock, ice) and/or protection solid and strong? T= Can this anchor be constructed in a timely manner? Just remember, ERNEST should be used as guidance, not a checklist—adjust as necessary. Once an anchor has been established, we must decide how to connect the rope to the anchor.

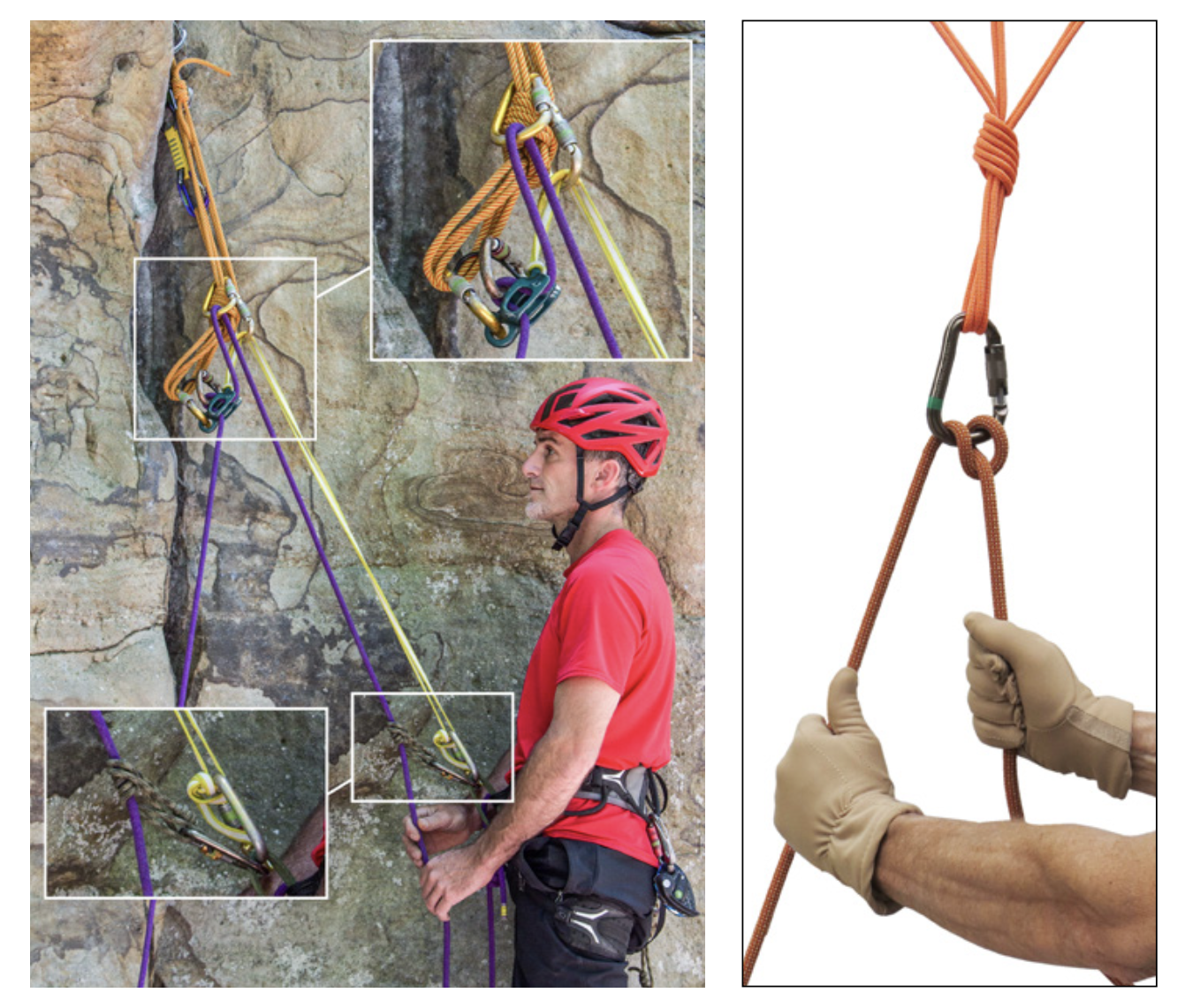

Sometimes a route may be too overhanging or traverse too much to clean by rappel. In such cases, it may be necessary to clip into the belay rope while lowering (a.k.a. “tram in”) to stay close to the wall and remove each piece. Be sure to communicate each step clearly with your belayer, and never unclip from the belay rope when you are away from the wall (as shown here), because you will plunge straight downward when the tension is released, possibly hitting the ground. Instead, only unclip from the belay rope when you’re clipped into a bolt or the belay rope is taut against the cliff face. Make sure to do this in a place where you won’t hit a tree or the ground when you swing off. PC: Andrew Burr

All top-roping should always be done through the climber’s removable gear, such as carabiners attached to quickdraws, runners, or a cordelette, and not through the fixed hardware of an existing anchor system. The fixed anchors should only be used for rappelling, where the ropes will be pulled without load. A dirty rope running through the anchor system under load causes unnecessary wear at fixed anchors. In fact, at some sandstone climbing destinations where sand easily works into the weave of the rope, locals are reporting 50 percent wear of steel quick- links in a couple of climbing seasons. So whether you are top-roping or topping out on a sport climb, be responsible and climb or lower on your own removable gear. Whenever possible, the last person to climb should rappel rather than lower off once he is finished with the route.

Before leading a sport climb, decide what extra gear will be needed for the anchor. To set up for lowering and top-roping, I like to carry two quickdraws designated for the anchor, one of them equipped with two locking carabiners. Before following a sport climb, decide what extra gear will be necessary to clean the top anchor. I girth-hitch two 24-inch nylon slings to my harness and add two locking carabiners. When I get to the anchor, I clip a locking carabiner to each rappel ring. Now I can thread the rope through the fixed anchor and rappel. There are a variety of techniques for accomplishing this. Regardless of the one you learn, I recommend practicing while on the ground and using the same system every time you clean the anchor.

One subtle but very important difference between rappelling and lowering is that in rappelling the rappel device is moving over a stationary rope, because the person rappelling is simply sliding down the rope. In lowering, the rope is the object in motion and is moving through a stationary belay device. This means the rope is moving over terrain that may have loose rock and/or sharp edges. In general a taut rope over a sharp edge is not a good idea, and one that is moving over sharp edges is just asking for trouble. Before lowering, take extra care to position the rope so it avoids any edges or loose blocks. And, finally, never lower with the rope running directly through an anchor sling—the hot friction of nylon on nylon will quickly melt through the sling, with disastrous consequences.

Be Prepared!

As climbers we all need to take ownership in the ability to problem-solve and be self-sufficient at the crag and in the mountains. This starts by critically thinking about what gear we carry on a given objective. For example, I choose to use an assisted-braking device (such as the Petzl Grigri) for top-roping, sport routes, and gym climbing because of the added security and comfort for holding and lowering a climber. In the mountains and on traditionally protected climbs I use an auto-blocking device (such as the Black Diamond ATC Guide or Petzl Reverso) because it is lighter, much more multifunctional, and it allows the rope to slip a bit when catching a fall, helping to reduce impact forces. Another example: I use accessory cord to tie my chalk bag around my waist, so I always have a cord I can easily convert into a prusik if I need to back up a lower or rappel.

In addition to my harness, protection, quickdraws, and shoulder-length slings, here’s what I typically carry on most multi-pitch climbs, giving me the tools to deal with most situations that might arise:

Small knife or multi-tool

Auto-blocking belay/rappel device with 2 locking carabiners

2–3 extra locking carabiners

5–7mm* cord to tie on chalk bag, doubling as a prusik cord

5–7mm*, 18-foot cordelette with a non-locking carabiner

Two 48” slings, each with a non-locking carabiner

1 extra 5–7mm*, 18-foot cordelette with rappel rings (for multi-pitch

alpine routes)

24” nylon sling for racking gear

* As a general rule, a cord or cordelette needs to be 2–3mm smaller than the climbing rope in order to provide adequate friction for a prusik.

FIGURE 4: When using an auto-blocking belay device in guide mode to belay a second climber, it may be necessary to “release” the locked device when it’s under load, in order to lower the second so he can reach a ledge or retry a move. Thread a thin sling through the small hole opposite the clip-in hole on the device, redirect it through the anchor, and clip it to your harness so you can use body weight to release the device. For additional control of the lower, always redirect the brake strand through the anchor. As a back-up, tie a friction hitch onto the brake strand and clip it to your harness. PC: Sterling Snyder

FIGURE 5: The Munter hitch can be used instead of a device to belay or lower a climber. It’s preferable to orient the hitch with the load strand on the gate side of the carabiner.

Since we are somewhat limited in the amount of gear we carry on a given objective, it makes sense to maximize our understanding of the gear we typically use. One of the most utilitarian pieces of modern equipment is a belay/rappel device with an auto-blocking option, like the BD ATC Guide, Petzl Reverso, or similar. This single piece of equipment has a variety of uses, including the following:

Standard belay from harness

Auto-blocking belay from an anchor (see Figure 4)

Lower from anchor with increasing friction (see Figure 3)

Lower from anchor with a backup (see Figure 2)

Simple 3:1 hauling system

Ascending

Rappelling

What if you drop your belay/rappel device? A key technique to know is how to tie a Munter hitch and use it to belay, rappel, or lower from a locking carabiner clipped to an equalized anchor (see Figure 5). When possible the Munter hitch should be tied so the load strand of the rope is on the gate side of the carabiner and the brake strand is on the spine side.

All of these skills and techniques should be practiced and perfected at your house, in the climbing gym, or at the local crag, in a setting that has minimal consequences if you get it wrong. And please take the time to read the instruction manuals that come with your equipment. They are packed with invaluable information and tips.

Through time, practice, observation, and reflection we start developing the necessary skills to be a truly competent partner, with the skills to use an alternative system when we, or our partner, can no longer climb, belay, lower, or rappel due to circumstances. I know for certain that we cannot possibly plan for everything that might happen in the mountains, but we all have a responsibility to our partner and the entire climbing community to be as prepared as possible when unexpected situations do arise.

About the Author

Mike Poborsky is an internationally certified rock, alpine, and ski guide, and is vice president of Exum Mountain Guides, based in Jackson, Wyoming.