Climbers stand up for the CORE Act, protecting the state’s outdoor heritage

by Lea Linse

*this article originally appeared in the AAC Summit Register, Issue 001

Tucked between the Rocky Mountains to the East and red deserts to the West lie 200,000 acres of quiet land known as the Thompson Divide. With its rolling hills, scrub forests, picturesque cattle pastures, and dusty sagebrush, the Divide lacks the grandeur and snow capped summits that you find in the nearby Maroon Bells-Snowmass Wilderness. It also lacks the throngs of summer hikers and incessant busy roads, instead offering meandering trails, trickling streams, and only a few quiet roads. Though it sits within an hour drive of the internationally renowned sport climbing mecca Rifle Mountain Park as well as the granite paradise of Independence Pass, I see why the Thompson Divide isn’t on climbers’ radar. It hosts only one small sport crag (a local favorite however), and the quality boulders, sport crags, and ice climbs around the tiny town of Redstone are just beyond the border of the Divide. While rock climbing isn’t going to put the Thompson Divide on the map, the Thompson Divide remains relevant to all of us.

In the last decade, the Thompson Divide gained notoriety as the centerpiece of a fierce grassroots campaign showcasing the importance of public land resources, and the value of citizen engagement in public land management.

The threat to development on the Thompson Divide has been long contested by Western Slope locals. Land of the Ute peoples. EcoFlight

The vast majority of the Thompson Divide is public land, managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the US Forest Service (USFS) for “multiple uses.” This land supports a wealth of agriculture, tourism, and recreational opportunities like hiking, climbing, biking, and hunting. The Thompson Divide has been at the heart of the Roaring Fork Valley ranching community for more than a century, supporting 30+ successful farms and cattle ranches that graze animals on this rich land.

As a kid growing up in Carbondale, I understood early on that my quality of life was greatly improved by the access we had to the outdoors. This meant building forts, going sledding (the Thompson Divide had the best sledding hill around), and eating cheeseburgers from grass-fed beef raised fifteen minutes up the road in the Thompson Divide. In high school, at a time when I was itching for more independence and an escape from teenage drama, the safe and accessible public lands on the Divide allowed me to satisfy those needs through outdoor recreation. There, I learned to backcountry ski, went on my first no-adults backpacking trip with friends, and led my first sport climb.

In the late 2000s, rumors surfaced that a Houston-based company wanted to drill for natural gas in the Thompson Divide. The company owned several natural gas leases there, but had yet to develop them. When leases are developed the impact is noticeable. Development includes the building of new roads, frequent use of heavy machinery and subsequent truck traffic, and multiple wells with automated pumps. The expansive spider web of infrastructure required to service these leases is evident in nearby towns along the I-70 corridor, where, if driving from the Front Range of Colorado to Utah, you could see numerous natural gas wells and related facilities. This sprawling network is even more visible from the air. This development falls mostly within Garfield County, home to Rifle Mountain Park. This county produced more natural gas than any other county in Colorado—sometimes more than twice as much as other leading counties—from 2007-2014.

Natural gas development in the Divide quickly became the talk of the town in Carbondale. There were new articles in the paper almost daily about the topic, which my mom would clip and save for me to read. I remember reading about the newly formed Thompson Divide Coalition (TDC) in 2007, a group that would become the soul of the grassroots effort to conserve the Divide. TDC is governed by a diverse volunteer board of local stakeholders like ranchers, small business owners, and community leaders who all agree on one thing—the Thompson Divide is a place too special to drill for natural gas. They made clear from the start that they weren’t against natural gas development on the whole, and many of them even cringed at being called “environmentalists.” Rather, they simply wanted what was best for their community.

Around the time that the TDC was formed, natural gas development in Garfield County was exploding as a result of technological advances and federal policies that encouraged rapid development. As natural gas wells became more numerous in rural communities such as Parachute, Silt, and Rifle, public health concerns associated with natural gas development were frequently reported by residents.

For example, in 2010, Garfield County released a Health Impact Assessment specific to a drilling plan in the nearby community of Battlement Mesa finding that, “[this] development plan is likely to change air quality and produce undesirable health impacts in residents living in close proximity throughout the community...”. Additionally, in 2011, the nonprofit Global Community Monitor found elevated levels of “22 toxic chemicals,” including hydrogen sulfide in the air near natural gas drilling sites (and rural homes) in Silt. And in 2013, there was a notable benzene leak confirmed in Parachute Creek, near several residential water wells.

Thompson Divide Coalition members speak with a Forest Service representative to encourage the preservation of the Divide. Land of the Ute peoples.

With this backdrop of contamination reports and health complaints, residents near the Thompson Divide were extremely concerned about the impacts of drilling near their homes. Still, research on the topic remained scarce and sometimes conflicting, such as in a 2017 study conducted by the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment that claimed “the risk of harmful health effects (was) low for residents living near oil and gas operations” but called for further research on exposure risks. We know now, however, following the updated report in 2019 by ICF, that emissions near drilling and hydraulic fracturing sites can cause serious negative health impacts.

In addition to health and pollution concerns, one of the strongest arguments for protecting the divide were the economic benefits. Benefits the community argued, relied on the land remaining undeveloped.

An economic impact analysis completed in 2013 found that recreation, agriculture, and tourism—activities that locals argued would be most negatively impacted by natural gas development—collectively contribute nearly 300 jobs and $30 million to the local economy each year. In a town of only 6,500 people in 2013—those numbers make a big difference. These uses of the Divide are also sustainable. They’ve provided for the community for generations and would continue to, so long as the Divide was left free of development. This was an argument that helped to rally a broad base of supporters, well beyond those whose health or property might be affected.

There are many other benefits to not allowing oil and gas in the Divide. Extracting carbon rich fuels and leaching methane into the air is counterproductive to combating climate change. Leaving fossil fuels in the ground is truly a form of climate action. In addition, several of the areas up for lease at the time were federally designated roadless areas. By cutting roads into these pristine areas, natural gas development would disrupt wildlife like deer and elk, pushing them out of critical winter ranges and disrupting their migration and calving grounds.

Five years after the Thompson Divide Coalition formed, the area was as threatened as ever. I knew I had to add my voice to the fight so I started a student led initiative aimed at engaging young people in this local issue. I spoke at a town hall meeting in front of nearly 300 people and later helped organize a student delegation to deliver 1,152 letters from concerned citizens to the BLM headquarters in Silt, CO, asking them to let the leases expire.

These experiences opened my eyes to the challenges of grassroots activism, and the importance of local land managers and government officials. In the case of mineral leasing, almost all of the key decisions that we were concerned about were being made right down the road, in local BLM offices, at county commission meetings, and in town halls by people who lived in our communities, not politicians in far away places. Because of the proximity of decision makers, and our efforts to engage them, I feel we made a significant difference, not only in our community, but in the trajectory of the Thompson Divide debate.

What would be a key decider for the fate of several leases on the Thompson Divide would be the environmental impact analysis the BLM was forced to conduct in accordance with the National Environmental Policy Act. As it turned out, the BLM’s first analysis was improperly conducted resulting in their issuing of the leases illegally.

When the BLM released the updated draft EIS in November 2015, they received over 50,000 comments—most in support of protecting the Divide and doing away with the illegal leases. For reference, the population of Carbondale and Glenwood Springs combined amounted to less than 20,000 people in 2016, demonstrating the widespread nature of support from all surrounding communities and businesses. On top of that, the BLM hosted 3 public meetings for citizens to raise concerns. One meeting in Carbondale turned out a whopping 240 people on a Wednesday night!

With the consistent outcry from the public, and the updated environmental analysis, the BLM decided to cancel 25 undeveloped leases in the heart of the Thompson Divide—a reality that would not have emerged without the NEPA process.

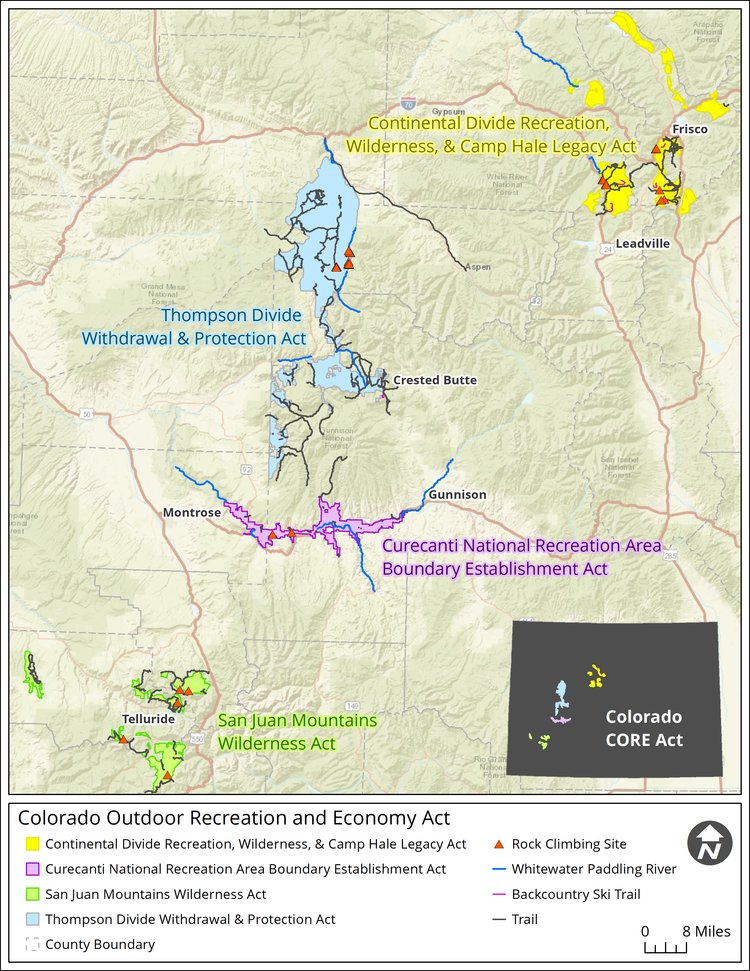

Though several of the leases in the Thompson Divide have been cancelled, the area has yet to be removed from future leasing. The hope of permanent protection was introduced in a bill sponsored by Senator Bennett in 2017 called the Thompson Divide Withdrawal and Protection Act, which has since been lumped into a larger package called the Colorado Outdoor Recreation Economy (CORE) Act.

The CORE Act could have economic and ecological benefits for regions in CO beyond the Thompson Divide.

The CORE Act, recognizes the economic and ecological benefits provided by public lands like the Thompson Divide, and would permanently withdraw the Divide from new leasing. The Act also introduces protections for recreational opportunities in other locations across Colorado—designating wilderness in the San Juans, protecting climbing areas in the 10 Mile Range and preserving climbing history by establishing a first-of-its-kind National Historic Landscape to honor Colorado’s military legacy at Camp Hale.

The CORE Act, however, has met significant political resistance from certain actors. Representative Tipton, for instance, introduced a similar bill of his own, the REC Act, which is nearly identical to the CORE Act except that it doesn’t include protection for the Thompson Divide. Reportedly, this omission was due to concerns from some of Tipton’s constituents, mainly the Garfield County Commissioners, who have consistently opposed protections for the Divide and sided with oil and gas companies. The Thompson Divide Coalition has implored residents of Garfield County to write to their commissioners and tell them to support protections for the Divide, but with seemingly little result.

It is frustrating to see this resistance continue to perpetuate from Garfield County to higher levels of the government. For example, citing Tipton’s concerns (which drew on Garfield County’s concerns), Senator Cory Gardner is now mounting resistance to the CORE Act in the Senate.

I believe the outpouring of community support, and especially its sincerity, is what distinguishes the Thompson Divide and earns it a place in federal legislation. Not only did residents take every opportunity to provide comments, attend community meetings, speak to their local government face-to-face, and write letters of support; they did so with a unique non-partisan sincerity that is difficult to ignore.

Supporting the protection of the Divide didn’t mean you were against oil and gas development in other areas where the impacts to the community and the local environment were less demonstrable. Nor did it mean you were an “environmentalist.” Supporting the Divide meant you cared deeply about the land, the wildlife, and the well-being of a healthy ecosystem, and that even development of essential mineral resources had to be sensitive to local and environmental needs. As one rancher famously quipped in an interview, “I ain’t no granola-crunching hippy,” but he shared the community belief that the Thompson Divide was too special of a place to drill.

While the Thompson Divide may not be home to one of our nations’ classic climbing areas, the protections afforded by the CORE Act preserve world class recreation all across Colorado. It preserves our climate by keeping carbon in the ground, safeguards public health and protects critical wildlife habitat by maintaining unfragmented forests. Land management challenges like that of the Thompson Divide are not unique, although the landscape is. Agency officials all over the country are making decisions about the future of our public lands and the energy development that occurs on them. Without the continued support of citizens like you, and the leadership of elected officials who share our concern for these places, they won’t receive the protections they rightfully deserve. There’s no time to be a silent bystander, we need to use our voice, go vote and spark the change we want to see.