This month, we recall a tragic accident from 2023 ANAC. While recalling this accident is disturbing, it’s important to understand that there were 14 published rappel accidents that year, eight of which resulted in fatalities. The trend shows no sign of abating. In the upcoming 2025 ANAC, our data tables record a total of 15 reported rappel incidents that involved 23 climbers and ended with five fatalities. It’s not all bad news. In the 2025 ANAC, we also feature an article with tips for improved rappel safety from John Godino of Alpinesavvy.com.

The west face of Tahquitz Rock was the scene of a tragic rappel accident in 2023 when two climbers fell to their deaths after an apparently solid rappel sling broke. Photo: Benjamin Crowell—Wikimedia.

Rappel Fatalities | Broken Anchor Sling

Tahquitz Rock, Riverside County, California

On Wednesday, September 28, 2022, Chelsea Walsh (33), a documentary filmmaker, and Gavin Escobar (31), an ex–Dallas Cowboys football player, died in a fall at Tahquitz Rock (Lily Rock). The Riverside Mountain Rescue Unit (RMRU) responded to the accident and later provided an in-depth analysis. They concluded that a degraded rappel sling caused the fatal fall of several hundred feet. This was one of two fatal accidents in 2022 due to a broken rappel-anchor sling.

RMRU reported that, around 8 a.m., Escobar and Walsh told another climbing party that they intended to climb Dave’s Deviation (3 pitches, 5.9). The weather appeared good, with only a few puffy clouds. At 10:30 a.m., a team on a route to the left, Super Pooper (5.10b), saw Escobar and Walsh near the top of their route. The weather was still good.

Fifteen to thirty minutes later, it began to rain. The team on Super Pooper began talking about retreating. By noon, the weather had gotten even worse. A team on Left Ski Track (5.6) had topped out and took shelter under a rock near the top of The Trough, a four-pitch 5.4. According to the RMRU report, by this time, “(the) weather has significantly deteriorated, with thunder and heavy rain and small hail. Members of both climbing parties were surprised at how quickly the storm intensified. Water was running down rock faces and soaked all climbing gear.”

Between noon and 12:15 p.m., the team on Super Pooper began to retreat. They heard a noise from the direction of Walsh and Escobar’s route and saw two falling climbers and a very large rock falling with them. The four climbers near the top of The Trough heard the same. No one heard rockfall before the sight and sounds of the fall. When RMRU arrived, they found Walsh and Escobar at the base of a gully below The Trough. The location of the bodies aligned with the fall line below a tree that was above the finish of Dave’s Deviation. Later investigation and video taken by Walsh confirmed the pair chose the tree—with an in situ rappel sling—as a bail point. The video also showed Escobar initiating the rappel and both climbers clipped into the single webbing loop. Both climbers appeared in good spirits and unhurried in making their rappel arrangements.

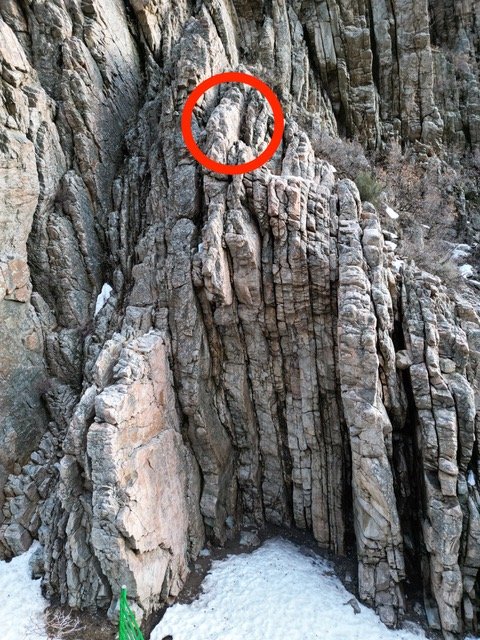

Above, we see the broken sling. At the time of the accident, this sun-bleached sling appeared darker/newer because it was wet from the rain storm that caused the climbers to rappel from this spot. Photo: James Eckhardt/RMRU.

The RMRU reported that the pair were found “wearing helmets, harnesses, and climbing shoes. Chelsea had a PAS girth-hitched through her harness with a locked screwgate at the far end, an unlocked screwgate clipped to an ATC, and an unlocked screwgate clipped to a hollow block. Chelsea was not connected to the rope or any anchor material. Gavin had a single-length sling girth-hitched to his harness’ tie-in points with an unlocked carabiner clipped to the sling and the belay loop. Additionally, an ATC was attached to his belay loop with a locked screwgate and both strands of the rope running through the ATC and through the screwgate. There was a four-to-five-foot loop of rope extending from the top of the ATC with two opposite and opposed wire-gate carabiners clipped to the rope. These carabiners were not connected to anything else. The rope had some sheath damage to the area around the ATC and significant sheath damage a few feet below the ATC, but there were no breaks present. Each end of the rope had a single figure 8 tied into it, one loose and one hand tight.”

The RMRU report summarizes, “As the storm moved in, the party reached the pine tree close to the first pitch of Upper Royal’s Arch and, given the conditions, decided to rappel. By the time they reached the pine tree, the webbing [around the tree] was wet, and as such, it would have been more difficult to ascertain the quality of the webbing without closely inspecting the knot and seeing the original color. They likely clipped into the webbing with their personal anchor systems. As the terrain below the pine tree is sloping, with only small areas to stand, it is likely they would have both been weighting the webbing. They then tied stopper knots into their rope, clipped it through the two wire-gates opposite and opposed, and dropped the ends. Gavin was first on rappel and descended a few feet before the webbing broke. As it was a single strand with no redundancy, both climbers fell. There was no evidence of rockfall hitting the tree or surrounding rock, and the webbing could not have been cut by a rock.

Video Analysis—Rappel Anchors

In this video, Jason Antin, IFMGA/AMGA Guide, gives some tips to avoid mistakes at the anchor:

Avoid rappelling from a single sling.

Avoid rappelling from an anchor made of old webbing.

White or gray nylon webbing is a red flag and needs closer inspection.

Beware of blotchy or faded webbing. Inspect the knot to try to spot an alternate (original) color inside. Try turning a sling over to look at its “under” side, against a tree or chockstone.

Carry a knotted sling or cordelette to back up anchors and a knife to cut away bad webbing and carry it out.

Credits: Pete Takeda, Editor of Accidents in North American Climbing, Jason Antin, IFMGA/AMGA guide; Producer: Shane Johnson and Sierra McGivney; Videographer: Foster Denney; Editor: Sierra McGivney; Location: Little Twin Owls, Lumpy Ridge, CO.

ANALYSIS

Rappelling from a single sling is not advisable. Nor is rappelling from an anchor comprised of old webbing. That said, most experienced climbers (the editors included) have at one time or another done both. Walsh and Escobar were very experienced and, based on their video, they felt in control of the situation. While the weather played a factor in their decision to retreat, it also indirectly played a role in the team’s decision to use the questionable rappel sling. The rain had made the sling appear in much better condition than it was. The RMRU report states, “The webbing felt old and stiff when dry, but when wetted, it felt significantly better and looked much less faded. It was gray/white…however, upon retrieval and closer inspection, it had originally been fluorescent green and was now fully faded from prolonged sun UV exposure.”

The RMRU report added that, “The unfaded color was visible in the knot, however it was very difficult to see without close inspection.” Any white or gray nylon webbing at an anchor is a red flag: Such webbing is sold, but it’s uncommon, and it suggests closer inspection. The same goes for any blotchiness (from fading) in the webbing. Inspecting the knot for soundness is a good step, for obvious reasons, but possibly spotting an alternate color inside the knot is also good reason to inspect it. Also, try turning a sling over to look at its “under” side, against a tree or chockstone. These days, sewn aramid-fiber slings are the norm. It is expensive to leave behind long looped runners as rappel anchors. To get around this problem, consider carrying a long knotted sling or cordelette that is better suited for backing up suspect anchors; a knife will be handy to cut the sling to length. This solution is inexpensive and reasonably light weight. (Sources: James Eckhardt, RMRU, and the Editors.)

These are images of the failed webbing rappel anchor from Tahquitz Rock. (A) Webbing as it was found on tree, with arrows indicating the two broken ends. (B) Image showing the full length of webbing retrieved with break and (C) close-up image of break. (D) Test 1: webbing broke at 2.54kN. (E) Test 2: webbing broke at knot at 3.56kN. Image also shows the original color (neon green) of the webbing. (F) Test 3: webbing broke at 3.2kN. Photos: RMRU.

Only a Few Days Left—Get the Shirt

Accidents in North American Climbing is one of climbing’s most historic and treasured publications. Get it with your American Alpine Club Membership! For the month of June only, also get the limited edition T-shirt!

Already a member? Donate $30 or renew in the month of June!

Use promo code: DIRTBAG